Shared Security Concerns with Opposite Outcomes: Myanmar and North Korea on China’s Border

Myanmar and North Korea are two of the fourteen states that share a border with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Authoritarian leaders have exclusively ruled both countries for the past fifty years, but Myanmar has recently begun a process of political liberalization. By contrast, North Korea continues to follow a path of economic and political isolationism. This essay will argue that both countries share a common security concern in their relations with China. Myanmar and North Korea have long been seen as clients of their massive neighbor, and have been consistently uneasy in this relationship. This unease has driven the countries down two very different paths, and has played a significant role in the geopolitical development of Asia in the 21st century.

One can explain Myanmar’s movements towards openness and North Korea’s continued isolation by examining the structural factors behind each state’s security concerns in relation to China. It is clear that North Korea’s relative influence over China is substantially more significant than Myanmar’s. This has enabled the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) to increase its dependence on China’s economic aid, propping up its own fledgling economy without fear of abandonment. On the other hand, Myanmar has relatively little strategic pull over the Chinese. Myanmar’s leaders have thus felt compelled to look towards western powers to avoid becoming the ‘twenty third Chinese province.’ Generally, these arguments point towards continued North Korean resilience, as long as its relative importance to China remains consistent.

The decision to liberalize is of course multifaceted and impossible to attribute to a single cause. Making a comparison between these two authoritarian regimes is further complicated by the uniqueness of North Korea’s political system. Still, a strong argument can be made about the shared variable of China as a neighbor (specifically the danger of being too dependent on any one benefactor) and its directional impact on the issue of liberalization in each country.[1]

Small States and Security

Both North Korea and Myanmar can be viewed as weak states, which play a fundamentally unique role in the international system. Annette Baker Fox argues that the successes of small states in resisting the pressure of great powers, “lay[s] in their capacity to convince the great-power belligerents that the costs of using coercion against them would more than offset the gains.”[2] These states will be able to extract concessions at especially high rates when there is strong competition between the major powers. Indeed, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea exploited this dynamic successfully throughout the Cold War, pushing the Soviet Union and China to compete for influence.[3] Myanmar has pursued a similar strategy, seeking a middle ground between India and China (though it has been considerably less successful).[4] Generally, weak states working to preserve their security through the concessions and support of larger powers will attempt to pursue a strategy of equal distance diplomacy—balancing between two patrons who hopefully do not like each other.[5]

Weak states will also face more serious security issues. As Robert Jervis writes, increases in one state’s security lead to a decrease in nearby states’ perceptions of their own security.[6] Because weak states are more likely to bandwagon than balance in response to a great power, they will depend on their patrons’ benevolence.[7] Thus, weak states are likely to become increasingly dependent on major powers; they will then become increasingly insecure in this dependency. As China becomes more powerful economically and militarily, Myanmar and North Korea will become more and more uneasy about their neighbor’s high level of influence. These states have two basic options: balance China’s clout by developing ties with another power or place increased confidence in China’s benevolence and support. In order to pursue the second strategy, the state must be especially certain that it will not be abandoned—it must have a high level of relative influence on the great power. Thus, one answer the question of why the DPRK has chosen to increase its reliance on China while Myanmar has looked towards the West can be found in the disparity between each countries respective level of influence on Beijing.

A comparison between North Korea and Myanmar is intuitive for several reasons; crucially, the two countries have refused to follow the East Asian development state model, and have subsequently remained among the world’s least developed nations.[8] In addition, their use of extensive repression has led the international community to condemn them as ‘pariah states’ in the post-Cold War era. This has pushed both to increase their reliance on China, as the PRC is often willing to support repressive regimes on its borders. Just as Myanmar and the DPRK present a natural comparison, empirical examination of the impact of an external backer (China, in both of these cases) on authoritarian longevity is valuable.[9] At present, there have been no comparisons of Myanmar and North Korea that focus on each state’s relationship with its shared great-power neighbor—China. Considering each state in this way will contribute to a greater understanding of its individual strategic decision—to pursue reform or retrenchment.

Current Perceptions of Myanmar and North Korea

This paper explains the shared security dilemma faced by Myanmar and North Korea. By treating the presence of China on each state’s borders as a common threat, one can draw comparisons about each state’s strategic options to mitigate this threat. Next, it measures the difference in Myanmar and North Korea’s relative influence on China by analyzing data on each state’s exports to China and high-level interactions between each state’s leaders and the leaders of the PRC. Finally, China’s changing behavior at its borders sheds light on the changing relative importance of the DPRK and Myanmar to the PRC. These two key comparisons lead to conclusions about the economic and strategic importance of the examined countries to their patron. After arguing that there is a difference between each country’s relative influence on China, the directional impact of the PRC on each state’s optimal strategy for security can be examined.

Myanmar and its Dilemma with China

Historically, China has been Myanmar’s main strategic threat.[10] While the leaders of both Myanmar and the PRC speak of their strategic partnership, the Burmese view Beijing with understandable trepidation. There are many reasons for this unease, and all of them speak to the security concern faced in Naypyitaw, the capital of Myanmar. This dilemma is centered on Myanmar’s economic and strategic dependence on China. First, Chinese investment is a dominating presence in the Burmese economy, and has led to substantial domestic discontent. The Chinese funded Myitsone Dam project faced tremendous opposition and was subsequently cancelled. Second, China has maintained close ties with the semi-autonomous minority groups that live at the Myanmar-China border. These groups have consistently fought Myanmar’s military government, and China’s attempts to balance between them have been met with resentment. Finally, the Chinese may intervene in Myanmar if there is further instability at the border or if Myanmar’s ruling regime becomes too destabilized. Each of these factors has contributed to the dilemma of dependency faced by Naypyitaw.

The development assistance provided by Beijing has been seen as proof of China’s status as Myanmar’s key backer.[11] As of 2009, China was the fourth largest international investor in Myanmar; since 2012, China has been the country’s principal financial sponsor.[12] However, the statistics certainly underestimate the true levels of investment, as many of the economic interactions between the two happen without Naypyitaw’s approval.[13] Some estimate that Chinese citizens own as much as sixty percent of Myanmar’s non-agricultural private businesses.[14] This has led to clear discontent, with embittered citizens expressing their grievances throughout the country.[15] Frustration with Chinese business practices reached a peak in 2011, when a sense of urgency developed around the need to protect the Irrawaddy River. This occurred just as the Chinese sponsored Myitsone dam would have imposed massive externalities on the communities surrounding Myanmar’s most significant river.[16] President Thein Sein subsequently decided to suspend work on the dam, partially in response to public pressure but primarily as a strategic move to check Chinese influence in Myanmar.[17]

The Chinese government has maintained close ties with the Wa and Kachin ethnic groups, who have historically fought against the Burmese government. In fact, the Chinese government has signed ceasefires directly with some of these ethnic minorities in exchange for access to some of their resources.[18] All of this has led to a multifaceted relationship between Naypyitaw, Beijing, and the leaders of these border communities. The involvement of the Chinese certainly contributes to unease in Myanmar’s leadership circles. In 2009 Myanmar’s army captured territory from the Kokang ethnic group, which is situated on China’s border.[19] This siege led to a public condemnation from Beijing, whose diplomatic snub irritated the Burmese and provoked their own response. For the first time in two decades, Myanmar’s official media published a story on the Dalai Llama.[20] The military leaders also warmly welcomed United States Senator Jim Webb to Yangon.[21]

Finally, the Chinese appropriately consider stability on their borders to be a core national interest.[22] Because of this concern, Chinese military intervention in Myanmar is not inconceivable. Myanmar’s liberalization is an inherently risky process. Its military dictators have long held the country together with force; it is not clear that the deep divisions between the regime and competing armed groups have been resolved.[23] A split in government could lead to a change in the current status quo of stability between the Burmese military and the armed militias.[24] If this change causes substantial conflict on China’s border, the PRC could intervene to ensure that its interests are protected. Since China generally focuses its approach to international affairs on non-intervention, this hypothetical intrusion seems highly unlikely (at least in the short-run); however, in 1988, China dispatched 20,000 troops to its border with Myanmar.[25] This was in response to the student-led democracy movement, and suggests that if Myanmar appeared to be on the verge of collapse, China would be ready to secure its own interests.[26] Of course, this threat poses a significant security risk for Myanmar’s military leadership. Overall, China’s disproportionate influence in Myanmar presents itself as a clear threat to Naypyitaw.

North Korea and its Dilemma With China

While China is simultaneously North Korea’s only official ally and benefactor, the DPRK experiences a security predicament that is surprisingly similar to Myanmar’s. First, trade with China utterly dominates North Korea’s fledgling economy; in fact, it represents half of DPRK imports and exports. In short, North Korean leaders are dependent on China to feed their people. Second, Chinese political and economic dominance of North Korea undermines the concept of Juche (which can be understood as an ideology of economic autarky) as a regime legitimating factor. Tangentially, the presence of the comparatively wealthy China makes the DPRK government look increasingly incompetent to its own people. Finally, China may be a military threat to the Kim dynasty.[27] As with Myanmar, the PRC may intervene if it expects a destabilizing regime collapse on its borders.

China’s economic dominance of North Korea is so significant that its Northeastern Provinces Promotion Plan counts the DPRK as the “Northeast’s fourth province.”[28] Indeed, international commerce between the two countries has spiked since around 2006, when the first nuclear test led to tighter sanctions on North Korea.[29] Since 2010, annual bilateral trade has exceeded North Korea’s trade with all other countries combined.[30] The reason for this dominance is that the domestic economy of the DPRK is hopelessly inefficient. In fact, most of its trade has historically been non-reciprocal: geopolitical concessions swapped for aid.[31] This is exemplified by the fact that North Korea has never recovered from the collapse of the Soviet Union. Trade with the USSR in 1990 was $2.6 billion; in 1991, trade with Russia was only $365 million.[32] More recently, in 2011 DPRK-Russia trade was a paltry $120 million.[33]

All of this is, of course, very troubling for the leadership in Pyongyang. In purely economic terms, China imports coal and electricity from the DPRK at prices well below those charged on the international markets.[34] In addition, North Korean buyers pay higher prices for Chinese oil than many other international customers.[35] Since the Kim dynasty had successfully avoided dependence on a single donor for decades, playing geopolitical rivals off of each other, this nearly complete reliance on China is a major strategic and economic dilemma for Pyongyang.[36]

China’s status as North Korea’s only patron is also troubling for the Kim regime’s ideological legitimacy. North Korea’s dogmatic raison d’etre in the post Cold-War world is focused on national independence, autonomy, and the strength of ideas over present realities.[37] This fits with Kim Il-Sung’s concept of Juche (or self sufficiency), which first became official policy in the 1960s.[38] Both China’s (and for that matter, South Korea’s) presence as a relatively wealthy neighbor and persistent donor undermine the Juche philosophy, which is demonstrated by changing propaganda patterns. Since the turn of the century, North Korean propagandists have stopped referring to South Korea as poor and backwards; the new story is that South Koreans have been corrupted by American capitalism.[39] This represents a substantial shift, and is one that has extended to China as well. Indeed, in 2011 the North Korean media published a ranking of the world’s happiest nations; Chinese people were ranked first, followed by North Koreans.[40] Changes in the average North Koreans’ access to information made the vast gap in living standards just north of the Tumen River impossible to ignore. The Kim dynasty’s domestic legitimacy is thus undermined by the presence of China at its borders and its perceived political clout as North Korea’s only backer.[41]

China has also normalized relations with Seoul, indicating Beijing’s focus on economics over ideology.[42] Here the dilemma for North Korea is that China has been clearly willing to move past their “relationship forged in blood.”[43] For North Korea, a state focused on the primacy of ideas over the circumstances on the ground, this materialism would be deeply disturbing. China’s perceived abandonment of Pyongyang in the international community would be further aggravated by the Chinese accession to United Nations Security Council sanctions in 2013.[44] It is clear that North Korea also faces a diplomatic dilemma with respect to Beijing’s moves in the international system.

China’s interests in North Korea are diverse; however, it is clear that an overarching goal of the PRC is to be the major power on the Korean Peninsula.[45] Thus, China would like to avoid unification by absorption (a situation where the Republic of Korea-United States alliance would suddenly reach its borders).[46] To that end, China may become a strategic threat to the DPRK if it expects instability that could lead to collapse. Indeed, the Chinese military has given substantial consideration to the intervention scenario; as Scott Snyder argues, “it is no accident that Chinese forces have moved closer to the Korean border in recent years.”[47] In 2003, Beijing mobilized 150,000 soldiers, sending them towards Korea.[48] Of course, this is troubling for Pyongyang, as North Korea’s perceptions of its own security are indisputably undermined by the looming presence of China.

Myanmar, North Korea, and China: Establishing the Gap in Relative Influence

Since the common concerns experienced by Myanmar and North Korea are centered on the presence of China as both a patron and threat, the directional impact of this shared variable is measurable.[49] First, exports will be interacted with high-level meetings. The results of this will demonstrate both a correlation between the two variables and a generally growing gap between Myanmar and North Korea. Second, China’s behavior towards Myanmar and North Korea at their respective borders will be compared over time. This comparison will demonstrate a change in China’s views on the salience of each country (or cynically, buffer zone) to its core strategic interests

Conclusions are limited by the fact that measuring Chinese perceptions of the relative importance of Myanmar and North Korea is imprecise. For the variable of trade and visits, both examined countries are not especially significant to China’s overall economic performance. When looking at China’s behavior at its borders, it is also possible that PRC strategists correctly perceive the situation on the border with Myanmar to be complex; in contrast, the border with North Korea is politically stable. As a result of these limitations, the predictive power of examining China as a force for either liberalization or retrenchment is certainly reduced. A more nuanced operationalization of influence would likely enhance the strength of the argument and its conclusions.

Trade and High-Level Visits

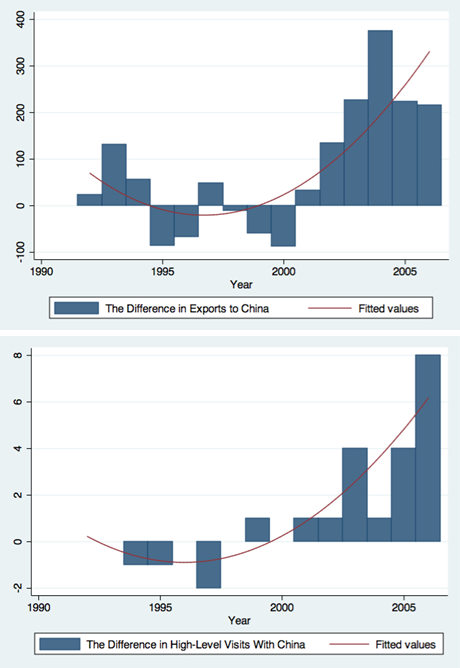

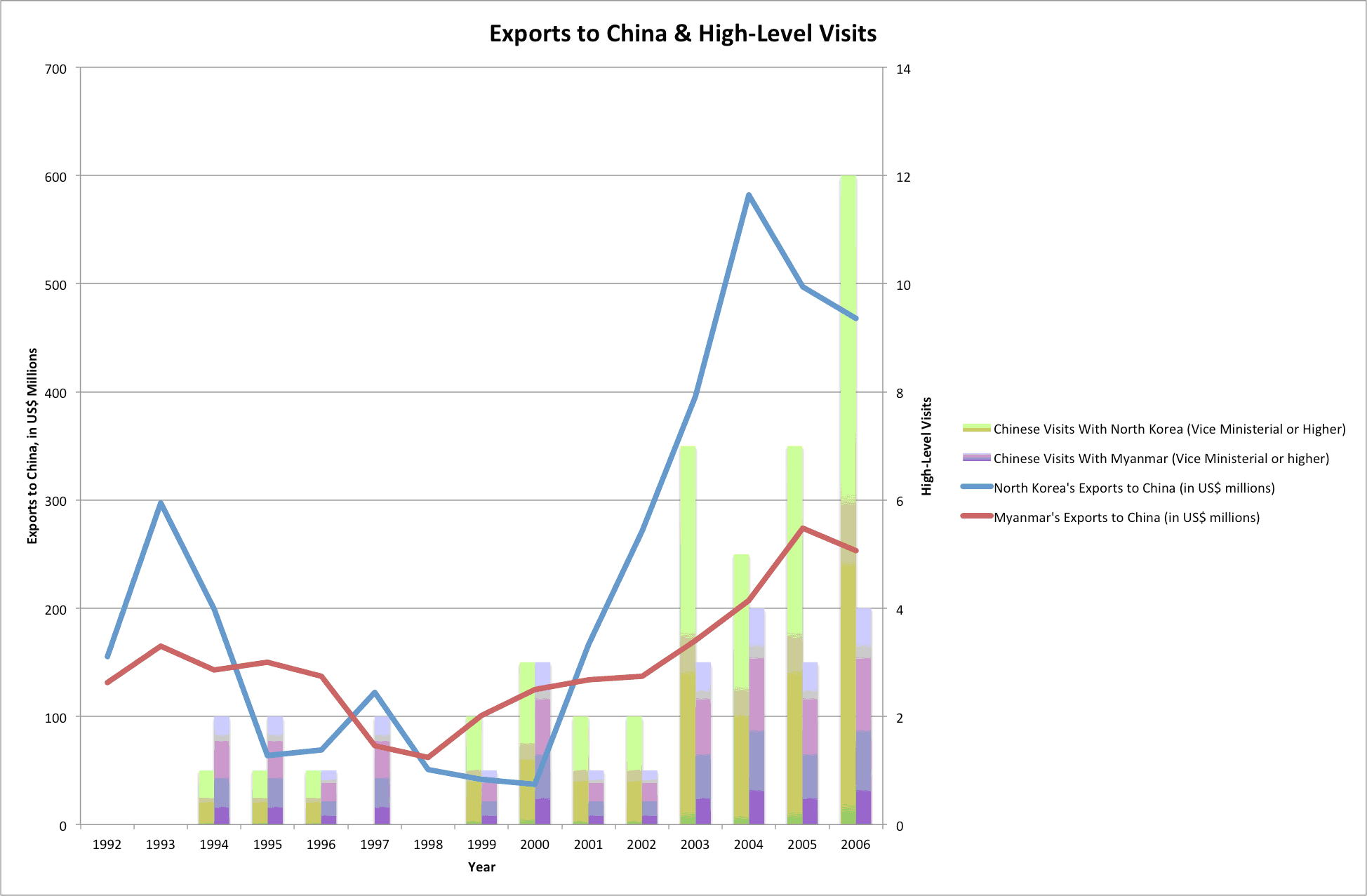

The included graphs show a correlation between exports and high-level interactions. For both Myanmar and North Korea, top-level meetings with Beijing have risen along with exports to China. In this analysis, high-level interactions are coded as those at and above the vice ministerial level. China’s imports from each country are examined as a more effective way to measure influence than net exports. In both countries, much of the investment flowing from China is unofficial and not reported, so inferences based on the overall balance will be less significant. Still, the same correlation and directional movements hold when substituting trade balance figures for China’s import data. From 1992 through 2000, all of these indicators were roughly comparable; from 2000 through 2006, they began to diverge.

The growing gap between North Korea and Myanmar in terms of exports to China is significant at the 99.9% level (p-value of 0.001). The same gap between North Korea and Myanmar in terms of high-level interactions with China is significant at the 98.4% level (p-value of 0.016). The correlation coefficient between these two interactions is 0.5563. Regression of the difference in interactions on the difference in exports is significant at the 97.9% level (p-value of 0.031). The r-squared value of this model is 31.3%. These results should be interpreted as correlational; as stated above, causal inferences are much more difficult to establish. Further studies would specifically benefit from the inclusion of more variables and data from before the fall of the Soviet Union.

Interactions Between Indicators of Relative Influence

This data shows that both North Korean exports and high-level interactions with China are substantially more significant than those of Myanmar. This supports the general claim that there is an influence gap and indicates that North Korea is both strategically and economically more important to China than Myanmar is. The following graph includes four of the variables, and highlights the trends in the data.

The reasons behind the year 2000 divergence are murky, but an informed discussion is beneficial to the larger argument. Some have argued that Chinese strategists wrote off the Kim regime as doomed to collapse following the fall of the Soviet Union.[52] This could explain China’s unwillingness to expend too much diplomatic and economic capital on Pyongyang until it became clear that the regime would survive the famine of the 1990s. Another possible explanation is that nascent capitalism in the post-famine DPRK made the country much more able to supply China with raw materials and thus more important to Beijing.[53] A final possibility is that the 2002 Nuclear Crisis combined with the quasi-official dispute over history between Beijing and Seoul to make the Chinese especially concerned about maintaining stability on the Korean Peninsula.[54] It seems likely that each of these factors coalesced in the early 2000s to drastically increase the relative influence of North Korea on China. Each of the presented explanations support the larger theory that there has been a growing gap between the way the Chinese view North Korea and Myanmar.

Border Disputes and Behavior

Another way to assess the relative influence of Myanmar and North Korea on China is to look at how China has responded to these two countries at its borders. If China is conciliatory towards the two proximate states, then their influence is high. If China is assertive, than their influence is low. Once again, an examination of broad trends indicates a divergence in relative influence that favors North Korea.

China has negotiated settlements to territorial disputes with both Myanmar and North Korea. Taylor Fravel’s study of these border disputes finds that the PRC is likely to compromise when it feels weak (whether domestically or internationally).[55] Fravel also finds that China settled territorial disputes with both Myanmar and North Korea only two years apart (1960 and 1962, respectively).[56] These disputes were of the exact same salience score (meaning the land was equally important to China) and of roughly comparable size.[57] China was intensely concerned with having good relations with its neighboring countries, and the indicators mentioned above suggest a rough equality between PRC perceptions of Myanmar and North Korea during the early 1960s.[58]

More recently, China’s treatment of each state at its borders has been anything but equal. China has developed and maintained relatively close relations with rebel groups on the Burmese border, even as these groups have been fighting the government in Naypyitaw.[59] As mentioned earlier, Beijing publicly condemned Burmese military operations on the border.[60] It is clear that China interacts with many actors at the Sino-Burmese border, in an attempt to ensure stability for its own interests; generally, Beijing demonstrates considerably less regard for the perceptions of Naypyitaw. The reasons for this change likely stem from the evolving political environment of the 1970s, which resulted in improvements to China’s security on the southern and eastern borders.[61]

In contrast, China’s treatment of North Korea at its border has been remarkably stable. China shows very little sympathy to North Korean defectors trying to enter its territory, calling them “economic migrants” instead of refugees.[62] This label enables China to forcefully repatriate all North Koreans caught in PRC territory. While there are definite economic motives for this behavior, China also strongly considers the impact of refugees on domestic North Korean politics.[63] Generally, China’s recent border policies towards North Korea focus on ensuring DPRK stability to a much greater extent than they do for Myanmar.

Once again, this differential indicates that China’s interests in North Korea are more significant than in Myanmar and that the DPRK has a higher level of relative influence on the Chinese. While Myanmar has gradually become more strategically relevant to China, the DPRKs level of significance to Beijing has increased to a much higher degree. This has compounded with the previously presented import and interaction data, generally explaining why the gap between Myanmar and North Korea in relation to China has grown over time.

The Directional Impact of The Relative Influence Gap on Liberalization

Now that the existence of the relative influence gap has been shown, the gap’s effect on Myanmar and North Korea will be examined. The key finding here is that Myanmar has worked to solve its dilemma vis-à-vis China by reforming itself and seeking closer ties with the West. In contrast, North Korea has worked to resolve the same dilemma by pursuing a strategy of isolation. Pyongyang has been able to go down this path because its relative influence on China is substantial: the DPRK can count on continued Chinese support.

How the Gap Pushed Myanmar towards Reform

Myanmar’s apprehension towards China has pushed it towards reform for two key reasons, neither of which applies to the leaders in North Korea. The first is that China has the clear upper hand in its dealings with Myanmar. Second, both Western countries and India have become more eager to engage with Myanmar’s leaders. Finally, as a natural comparison, Mongolia and Myanmar have pursued surprisingly similar strategies for managing the potential threat of China.

Looking at security issues, it is clear that China has a very strong advantage over Myanmar.[64] The Ramree Island off of the Rakhine Coast, Hainggyi Island, Monkey Point (in Yangon), and Zadetky Kyun Island are all leased to the Chinese military.[65] Thus, China has a military presence throughout Myanmar’s territory. Presumably, these bases are intended to provide a mechanism for power projection into the Bay of Bengal in the event of a crisis with India. As a corollary, Myanmar’s acceptance of an internal Chinese military presence has the secondary effect of antagonizing Delhi.[66]

Burmese leaders have become increasingly uncomfortable with the Chinese army’s dominance, and have begun seeking military training from India, Pakistan, Russia, and even North Korea.[67] Myanmar’s discomfort with China’s strategic supremacy began to impact decision-making around the same time that other regional powers were attempting to balance against Chinese influence. When India started to pursue a “Look East” policy, in a clear attempt to dilute Chinese dominance of Southeast Asia, Myanmar’s leaders reacted positively.[68] As the Burmese moved towards India, many predicted that China would neglect the aforementioned strategic partnership and focus on deepening ties with other border states. Some of this speculation actually came from within China itself. Indeed, an influential Chinese academic article argued that the PRC should further strengthen its ties with the armed border militias, abandoning the leadership in Naypyitaw.[69] This sentiment in China further increases the incentives for Burmese reform, as Myanmar’s leaders will have felt that they could not rely on Beijing.[70] China’s strategic dominance in Myanmar had two crucial effects on the decision to liberalize in Naypyitaw. First, it provided clear incentives to develop ties with other states; second, it provided incentives for other states to pursue rapprochement with Myanmar.

Chinese strategic dominance of Myanmar provided the impetus for reform because it changed the incentives for both the generals in Naypyitaw and the leaders of Western democracies. Myanmar’s generals felt the need to reengage with the West to reduce China’s disproportionate influence. To do that, it was necessary to bring the popularly supported opposition movement back into the folds of government;[71] resolving Myanmar’s dilemma with China necessitated the deepening of ties with western powers.[72] In fact, the government of Myanmar faces a kind of zero-sum political tradeoff. In order to reduce its dependence on China it must increase its relations with the West, but increasing relations with the West requires further concessions to the opposition and thus further reform.[73]

While it is currently unclear how far Myanmar’s leaders will take liberalization, the reasons behind their decision to reform are coming into focus.[74] China had complete strategic dominance of the country, a situation that was untenable to Naypyitaw. The dilemma was exacerbated by the fact that Myanmar’s leaders had little leverage to ensure long-term Chinese support. Overall, Myanmar’s generals could not rely on China, so reform was necessary to dilute Chinese influence and improve relations with the West.

A Case Study: Mongolia and China

Mongolia has faced a dilemma with respect to China that is very comparable to Myanmar’s. China’s economic dominance of Mongolia prompted Ulaanbaatar to cultivate relations with other countries.[75] Resentment with Chinese business practices has spread from society to state, with legislation enacted that will curtail Ulaanbaatar’s dependence on Beijing.[76] If Chinese economic expansion alienates the citizens of satellite countries; these nations then have incentives to balance against Chinese influence by deepening ties with other powers.[77] Because Myanmar’s liberalization is lagging behind Mongolia’s, Ulaanbaatar may provide a model for strategically minded reformers in Naypyitaw—the MPRP’s continued influence in Mongolian politics indicates that reform is not tantamount to a complete loss of power.

How The Gap Pushed North Korea Towards Retrenchment

North Korea’s dilemma has pushed it towards retrenchment because of its high level of relative influence on the PRC. Simply put, the DPRK can count on China’s support, both financially and strategically. This enables Pyongyang to increase its dependence on Beijing without fear of abandonment.

North Korea can exert more pressure on China than China can exert on North Korea. To illustrate this puzzling point, one can think about the North’s seemingly counterintuitive (but persistent) military provocations. On the ground, the DPRK will lose in any confrontation with the South. However, Andrei Lankov has argued that North Korea will actually win any small-scale battle between the two Koreas.[78] This is because the South Koreans cannot inflict damage on anything strategically significant to Pyongyang without fighting a full-scale war. On the other hand, any confrontation between the North and the South is likely to have significant negative consequences for the democratically elected politicians in Seoul.[79] The South Koreans can destroy the North, but they cannot do much to influence its behavior.

China faces a nearly identical situation.[80] Because North Korea is dependent on the PRC, it is so vulnerable that China cannot really do much to influence it.[81] As Lankov writes, China doesn’t actually have any leverage over Pyongyang:

“What it has is not a lever, but a hammer. China can knock North Korea unconscious if it wishes, but it cannot really manage its behavior.”[82]

This massive power asymmetry goes back to the relevant theories on the power of weak states.[83] Simply put, if Beijing were to use coercion to influence Pyongyang, the costs would likely outweigh the gains. As such, the massive balance of power gap presents itself as (for lack of a better phrase) a characteristic case of the tail wagging the dog.

While China cannot truly influence North Korea, it also cannot abandon the DPRK. China considers North Korea to be a strategically vital buffer zone against outside powers.[84] This is because a unified Korea would almost certainly ally with the United States.[85] Since China’s leaders fear encirclement, the Republic of Korea (ROK)-United States alliance must not be allowed to reach the borders of the PRC. Chinese leaders face their own security issue on the Korean Peninsula, as they now bear sole responsibility for keeping the DPRK stable.[86] This task has been complicated by United States policy towards North Korea, which has typically focused on regime change and unification by absorption.[87] Overall, the need to maintain a buffer against other powers ensures that China’s main strategic goal on the Korean Peninsula is (and will remain) the maintenance of the status quo.

There are other reasons for China to support the DPRK, the most salient of which are economic. The Chinese Communist Party enjoys performance legitimacy, and continued economic growth is vital to its resiliency.[88] The massive flood of refugees in the event of a North Korean collapse would certainly lead to declining economic performance in China’s northern provinces.[89] In addition, the hopelessness of the North Korean economy actually provides short-term economic advantages to Beijing; China is able to extract the natural resources of the DPRK at minimal cost.[90] In general, the Chinese will not abandon the DPRK anytime soon, a fact that Pyongyang is well aware of.

The fact that North Korea’s relative influence on China is significant leads to the conclusion that the DPRK can both influence and count on the PRC. This has enabled North Korea to avoid reform and actually increase its dependence on the Chinese. Even though they are uneasy in this dilemma of dependence, Pyongyang can be confident that it will retain Chinese support. Indeed, Stephan Haggard argues that, even though Chinese leaders may encourage their nominal allies in the DPRK to enact official economic liberalization, their politically supportive policies reduce the prospective payoffs of economic reform.[91] Further, during the height of the Six-Party Talks, North Korean diplomats were able to successfully play China’s overarching focus on stability off of the United States and other powers to extract maximum concessions.[92] Overall, North Korean leaders have exploited their mutual dilemma of dependence with the PRC to avoid reform and obtain maximum concessions from the international community.

|

Security Concern with China’s presence |

Relative Influence on China |

Optimal Strategy-reform or retrenchment? |

|

|

North Korea |

Substantial, the DPRK is very dependent on the PRC | Substantial, the DPRK can count on continued Chinese support | Incentives to avoid reform, North Korea can mitigate its security dilemma with China by continuing its current policies |

|

Myanmar |

Substantial, Myanmar is very dependent on the PRC | Limited, Myanmar cannot count on continued Chinese support | Incentives to reform, Myanmar must seek other backers to mitigate its security dilemma with China |

Conclusions

In conclusion, the shared threat of China provides an interesting and underutilized way to examine the strategic decision to pursue reform or retrenchment in North Korea and Myanmar. By arguing that the two aforementioned countries face a similar security threat in Beijing, analysis on the shared variable of China and its impact on the binary choice of reform can be conducted. This paper argues that North Korea has much more influence on the Chinese than Myanmar does. This stark difference in relative influence has enabled the Kim Dynasty to increase its dependence on the PRC to unprecedented levels. Because Pyongyang does not have to be especially worried about Chinese abandonment, it can avoid being overly concerned with its security predicament. In contrast, Myanmar’s leaders face an opposite scenario. They could not depend on the Chinese for unequivocal support, and thus chose to reform and look towards the West.

This analysis has focused on bilateral relationships. Further examinations of the impact of outside powers on the relations between the examined countries would be beneficial. Specifically, detailed studies on Chinese perceptions of the significance of the international community may strengthen the presented arguments on relative influence. If the Chinese leadership concerns itself with international norms, than their support for North Korea (in the face of widespread criticism) would provide more evidence for the significance of Pyongyang.[93]

These conclusions imply that, all else equal, the Kim dynasty will muddle along for as long as Beijing views the North Korean buffer zone as crucial to Chinese national interests. At the moment, the most plausible situation that would change this calculation is the fall of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Thus, it seems likely that Pyongyang will continue its despotic rule for as long as the CCP remains in power. Conversely, it seems likely that Myanmar will continue on its path to reform, as long as Western engagement continues.

Works Cited

Armstrong, Charles K. “Ideological Introversion and Regime Survival: North Korea’s “Our Style Socialism.” In Why Communism Did Not Collapse: Understanding Authoritarian Regime Resilience in Asia and Europe, edited by Martin K. Dimitrov, 99-123. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Armstrong, Charles K. Tyranny of the Weak. North Korea and the World, 1950-1992. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013.

Byoung-Kon, J., and K. Jang-Ho. “China’s Role and Perception of a Unified Korea.” The Korean Journal of Defense Anaylsis 25, no. 3 (2013): 369-83. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1497642237?accountid=14437.

Cho, S. “North Korea’s Security Dilemma and Strategic Options.” The Journal of East Asian Affairs 23, no. 2 (2009): 69-103. http://search.proquest.com/docview/754064868?accountid=14437.

Cook, Alastair. “Myanmar’s China Policy: Agendas, Strategies, and Challenges.” China Report 48, no. 3 (2012): 269-81. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0009445512462745.

Fox, Annette B. The Power of Small States: Diplomacy in World War II. Chicago, IL, U.S.A.: University of Chicago Press, 1959. 8-9.

Fravel, Taylor. Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China’s Territorial Disputes. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Guilloux, Alain. “Myanmar: Analyzing Problems of Transition and Intervention.” Contemporary Politics 16, no. 4 (2010): 383-401.

Haggard, Stephan, and Marcus Noland. Famine in North Korea: Markets, Aid, and Reform. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007.

Haggard, Stephan, and Marcus Noland. Witness to Transformation: Refugee Insights into North Korea. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute For International Economics, 2011.

“Introduction.” In North Korea in Transition: Politics, Economy, and Society, edited by Kyung-Ae Park and Scott Snyder. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2013.

Jervis, Robert. “Cooperation under the Security Dilemma.” World Politics 30, no. 02 (1978): 167-214.

Jinyun, Liang. “The Situation in Myanmar and Its Impact on China’s Security Strategy.” 云南警官学院学. Accessed April 09, 2014. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-YNGZ201105016.htm. (Chinese)

Jong-Ho, Nam, Choo Jae-Woo, and Lee Jang-Won. “China’s Dilemma on the Korean Peninsula: Not an Alliance but a Security Dilemma.” The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis 25, no. 3 (2013): 385-98. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1497642320?accountid=14437.

Kang, David. “”China Rising” and Its Implications for North Korea’s China Policy.” In New Challenges of North Korean Foreign Policy, edited by Kyung-Ae Park, 113-33. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Lankov, Andrei. “North Korea Lacks Rich Relation in Russia.” Asia Times Online. September 18, 2012. http://atimes.com/atimes/Korea/NI18Dg01.html.

Lankov, A. N. The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Lee, Chae Jin. China and Korea: Dynamic Relations. Stanford: Hoover Press, 1996.

Manyin, Mark. “Food Crisis and Aid Diplomacy.” In New Challenges of North Korean Foreign Policy, edited by Kyung-Ae Park. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Ming, Liu. “Changes and Continuities in Pyongyang’s China Policy.” In North Korea in Transition: Politics, Economy, and Society, edited by Kyung-Ae Park and Scott Snyder. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2013.

Myers, B. R. The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves and Why It Matters. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House, 2010.

Narayanan, Raviprasad. “China and Myanmar: Alternating between ‘Brothers’ and ‘Cousins'” China Report 46, no. 3 (2011): 253-65.

Nathan, Andrew J., and Andrew Scobell. China’s Search for Security. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012. 126-38.

Nato, Dick, and Mark Manyin. China-North Korea Relations. Report. Congressional Research Service (2010): 15

Oberdorfer, Don. The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books, 2013.

Pak, K. “China’s Cost Benefit Analysis of a Unified Korea: South Korea’s Strategic Approaches.” The Journal of East Asian Affairs 26, no. 2 (2012): 25-55. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1322715495?accountid=14437.

The People’s Republic of China. Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Bilateral Relations in 2006. Pyongyang.

Reeves, Jeffrey. “China’s Unraveling Engagement Strategy.” The Washington Quarterly 36, no. 4 (December 12, 2013): 139-49.

Roehrig, Terrence. “History as a Strategic Weapon: The Korean and Chinese Struggle over Koguryo.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 45, no. 1 (2010): 5-28.

Rossabi, Morris. “Sino-Mongol Border.” In Beijing’s Power and China’s Borders: Twenty Neighbors in Asia, edited by Bruce A. Elleman, Stephen Kotkin, and Clive H. Schofield, 169-84. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2013.

Scobell, Andrew. China and North Korea: From Comrades-in-Arms to Allies at Arm’s Length. Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2004. http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/websites/armymil/www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/pdffiles/00364.pdf.

Scobell, Andrew. “China and North Korea: The Close But Uncomfortable Relationship.” Current History 101, no. 656 (2002): 278-83. http://search.proquest.com/docview/59896555?accountid=14437.

Scobell, Andrew. “China and North Korea: The Limits of Influence.” Current History 102, no. 665 (2003): 274-78. http://search.proquest.com/docview/59861757?accountid=14437.

Snyder, Scott. China’s Rise and the Two Koreas: Politics, Economics, Security. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2009. 41+.

Steinberg, David I., and Hongwei Fan. “Introduction.” Introduction to Modern China-Myanmar Relations: Dilemmas of Mutual Dependence. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2012.

Steinberg, David I., and Hongwei Fan. Modern China-Myanmar Relations: Dilemmas of Mutual Dependence. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2012.

Steinberg, David I. Modern China-Myanmar Relations: Dilemmas of Mutual Dependence. Copenhagen: University of Hawaii Press, 2012.

Sutter, Robert. “Myanmar in Contemporary Chinese Foreign Policy – Strengthening Common Ground, Managing Differences.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 31, no. 1 (2012): 29-51. http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs14/JCSAA31-01-Sutter.pdf.

Szalontai, Balázs, and Changyong Choi. “China’s Controversial Role in North Korea’s Economic Transformation: The Dilemmas of Dependency.” Asian Survey 53, no. 2 (2013): 269-91. doi:http://dx.doi.org/AS.2013.53.2.269.

U.S. Policy Towards Burma: Testimony Before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs(2012) (testimony of Joseph Yun).

Walt, Stephen M. “Alliances: Balancing and Bandwagoning.” In The Origins of Alliances, 110-12. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987.

Zin, Min, and Brian Joseph. “The Opening in Burma: The Democrats’ Opportunity.” The Journal of Democracy 23, no. 4 (2012): 104-19.

Footnotes

[1] This analysis will treat reform as a binary decision: no statements will be made on degrees of liberalization. The essay focuses on the strategic choice of reform, not the reforms themselves.

[2] Annette B. Fox, The Power of Small States: Diplomacy in World War II. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959), 8-9.

[3] Charles K. Armstrong, Tyranny of the Weak. North Korea and the World, 1950-1992. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013), 3.

[4] Raviprasad Narayanan, “China and Myanmar: Alternating between ‘Brothers’ and ‘Cousins'” China Report 46.3 (2011):], 261-63

[5] Andrei N. Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013) 73.

[6] Robert Jervis, “Cooperation under the Security Dilemma.” World Politics 30.02 (1978), 170.

[7] Stephen M. Walt, “Alliances: Balancing and Bandwagoning.” The Origins of Alliances. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987), 110-12.

[8] Balázs Szalontai, and Changyong Choi. “China’s Controversial Role in North Korea’s Economic Transformation: The Dilemmas of Dependency.” Asian Survey 53.2 (2013), 288.

[9] “Introduction.” North Korea in Transition: Politics, Economy, and Society. Ed. Kyung-Ae Park and Scott Snyder (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013)

[10] Robert Sutter, “Myanmar in Contemporary Chinese Foreign Policy – Strengthening Common Ground, Managing Differences.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 31.1 (2012), 48. <http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs14/JCSAA31-01-Sutter.pdf>.

[11] David I. Steinberg and Hongwei Fan, Modern China-Myanmar Relations: Dilemmas of Mutual Dependence. (Copenhagen: University of Hawaii, 2012), 220.

[12] Min Zin and Brian Joseph, “The Opening in Burma: The Democrats’ Opportunity.” The Journal of Democracy 23.4 (2012), 107.

[13] David I. Steinberg and Hongwei Fan, Modern China-Myanmar Relations: Dilemmas of Mutual Dependence. 231.

[14] Ibid. 363.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Min Zin and Brian Joseph, “The Opening in Burma: The Democrats’ Opportunity.” 109.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Cook, Alastair, “Myanmar’s China Policy: Agendas, Strategies, and Challenges.” China Report 48.3 (2012), 276.

[19] Raviprasad Narayanan, “China and Myanmar: Alternating between ‘Brothers’ and ‘Cousins.’” 259.

[20] Publicizing the activities of Tibet’s exiled leader is a clear rebuke of Beijing

[21] Raviprasad Narayanan, “China and Myanmar: Alternating between ‘Brothers’ and ‘Cousins.’” 259.

[22] Robert Sutter, “Myanmar in Contemporary Chinese Foreign Policy – Strengthening Common Ground, Managing Differences.” 31.

[23] Alain Guilloux. “Myanmar: Analyzing Problems of Transition and Intervention.” Contemporary Politics 16.4 (2010), 385.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid. 390.

[26] Ibid. 390.

[27] The Kim dynasty is currently in its third generation, Kim Jong Un is the President of the DPRK

[28] S. Cho, “North Korea’s Security Dilemma and Strategic Options.” The Journal of East Asian Affairs 23.2 (2009), 89. <http://search.proquest.com/docview/754064868?accountid=14437>.

-For more on the Northeast Provinces Promotion Plan, see J.S. Yang and S.M. Wu, “Deepening of DPRK’s Economic Dependence to China and Its Prospects”, EximBank North Korean Economy, Korea EximBank, 2005(winter).

[29] Andrei N. Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. 179

[30] Ibid.

[31] Andrei N. Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. 73.

[32] Andrew Scobell, “China and North Korea: The Close But Uncomfortable Relationship.” Current History 101.656 (2002), 281. <http://search.proquest.com/docview/59896555?accountid=14437>.

[33] Andrei Lankov, “North Korea Lacks Rich Relation in Russia.” Asia Times Online. September 18, 2012. http://atimes.com/atimes/Korea/NI18Dg01.html.

[34] Andrei N. Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. 183.

[35] Balázs Szalontai and Changyong Choi, “China’s Controversial Role in North Korea’s Economic Transformation: The Dilemmas of Dependency.” 281.

[36] Andrei N. Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. 183

[37] Charles K. Armstrong, “Ideological Introversion and Regime Survival: North Korea’s “Our Style Socialism”.” Why Communism Did Not Collapse: Understanding Authoritarian Regime Resilience in Asia and Europe. Ed. Martin K. Dimitrov. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 111.

[38] Charles K. Armstrong, Tyranny of the Weak. North Korea and the World, 1950-1992. 53

[39] Andrei N. Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. 105

[40] Ibid. 56.

[41] B.R. Meyers’s arguments on the Kim Regime’s domestic legitimacy are not incompatible with this line of thought. He argues that the DPRKs ideology is based on the purity and innocence of the Korean race, and that a strong leader is thus necessary to prevent the race from being victimized. This implies that North Korea’s dependence on China makes the Kim Dynasty look weak at home.

[42] Don Oberdorfer, The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History, (Basic, 2013), 247.

[43] Chae Jin Lee, China and Korea: Dynamic Relations. (Stanford: Hoover, 1996), 115.

[44] Nam Jong-Ho, Choo Jae-Woo, and Lee Jang-Won, “China’s Dilemma on the Korean Peninsula: Not an Alliance but a Security Dilemma.” The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis 25.3 (2013), 385. <http://search.proquest.com/docview/1497642320?accountid=14437>.

[45] J. Byoung-Kon and K. Jang-Ho, “China’s Role and Perception of a Unified Korea.” The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis 25.3 (2013), 372. <http://search.proquest.com/docview/1497642237?accountid=14437>.

[46] Nam Jong-Ho, Choo Jae-Woo, and Lee Jang-Won, “China’s Dilemma on the Korean Peninsula: Not an Alliance but a Security Dilemma.” 397.

[47] Scott Snyder, China’s Rise and the Two Koreas: Politics, Economics, Security. (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2009), 156.

[48] Andrew Scobell, China and North Korea: From Comrades-in-Arms to Allies at Arm’s Length. (Carlisle Barracks: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2004), 24. <http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/websites/armymil/www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/pdffiles/00364.pdf>.

[49] I have chosen to exclude China’s behavior in The United Nations from this analysis. China has typically prevented sanctions from being imposed on both countries. However, China did support restrictions on DPRK arms trade in 2013. This seems to be an exception of the norm rather than an indication that Beijing is moving away from North Korea. Because China, has not enforced sanctions (even the ones that it supported) this does not indicate a notable decline in Pyongyang’s relative influence. China’s behavior at the UN is complicated by the fact that international organizations are fundamentally multilateral. Focusing on UN votes is thus unlikely to allow comparisons to be drawn between the bilateral relations of the examined countries.

[50] Data gathered from:

Dick Nato and Mark Manyin. China-North Korea Relations. Rep. (Congressional Research Service, 2010); Scott Snyder, China’s Rise and the Two Koreas: Politics, Economics, Security. 41, 215-219; David I. Steinberg and Hongwei Fan, Modern China-Myanmar Relations: Dilemmas of Mutual Dependence. 209, 390-419; The People’s Republic of China. Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Bilateral Relations in 2006. Pyongyang: n.p.,

[51] Data is consistent across both graphs

[52] Andrei N. Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. 179.

[53] Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland, Famine in North Korea: Markets, Aid, and Reform. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 173..

[54] For more on the dispute, see: Terrence Roehrig, “History as a Strategic Weapon: The Korean and Chinese Struggle over Koguryo.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 45.1 (2010), 5-28.

[55] M. Taylor Fravel, Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China’s Territorial Disputes. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008) 38.

[56] Ibid. 46.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Ibid. 57.

[59] Alastair Cook, “Myanmar’s China Policy: Agendas, Strategies, and Challenges.” 276

[60] See page 7.

[61] David I. Steinberg and Hongwei Fan, Modern China-Myanmar Relations: Dilemmas of Mutual Dependence. 149

[62] Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland, Witness to Transformation: Refugee Insights into North Korea. (Washington: Peterson Institute For International Economics, 2011), 146.

[63] Andrew Scobell, China and North Korea: From Comrades-in-Arms to Allies at Arm’s Length. 22.

[64] Raviprasad Narayanan, “China and Myanmar: Alternating between ‘Brothers’ and ‘Cousins'” 262.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ibid. 263.

[67] Min Zin and Brian Joseph, “The Opening in Burma: The Democrats’ Opportunity.” 108.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Liang Jinyun, “The Situation in Myanmar and Its Impact on China’s Security Strategy.” (2011): 云南警官学院学 CNKI. <http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-YNGZ201105016.htm>. (Chinese)

[70] Admittedly, the evidence for this is somewhat circumstantial. Still, the presented evidence indicates that Myanmar has not been able to count on China. The logical conclusion of this is increased incentives for reform.

[71] Min Zin and Brian Joseph, “The Opening in Burma: The Democrats’ Opportunity.” 110.

[72] See: U.S. Policy Towards Burma: Testimony Before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs(2012) (testimony of Joseph Yun).

[73] David I. Steinberg and Hongwei Fan, Modern China-Myanmar Relations: Dilemmas of Mutual Dependence. 364.

[74] Ibid. 372.

[75] Morris Rossabi, “Sino-Mongol Border.” In Beijing’s Power and China’s Borders: Twenty Neighbors in Asia, edited by Bruce A. Elleman, Stephen Kotkin, and Clive H. Schofield, (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2013), 182

[76] Jeffrey Reeves, “China’s Unraveling Engagement Strategy.” The Washington Quarterly 36, no. 4 (December 12, 2013): 146.

[77] Ibid.

[78] Andrei N. Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. 178.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Andrew Scobell, “China and North Korea: The Limits of Influence.” Current History 102.665 (2003), 277. <http://search.proquest.com/docview/59861757?accountid=14437>.

[81] David Kang, “China Rising and Its Implications for North Korea’s China Policy.” New Challenges of North Korean Foreign Policy. Ed. Kyung-Ae Park. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 126.

[82] Andrei N. Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. 185.

[83] See pages 3-4

[84] K. Pak, “China’s Cost Benefit Analysis of a Unified Korea: South Korea’s Strategic Approaches.” The Journal of East Asian Affairs 26.2 (2012), 37. <http://search.proquest.com/docview/1322715495?accountid=14437>.

[85] Andrew J. Nathan and Andrew Scobell, China’s Search for Security. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 136.

[86] Nam Jong-Ho, Choo Jae-Woo, and Lee Jang-Won, “China’s Dilemma on the Korean Peninsula: Not an Alliance but a Security Dilemma.” 392.

[87] Ibid.

[88] Andrei N. Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. 180.

[89] Mark Manyin. “Food Crisis and Aid Diplomacy.” New Challenges of North Korean Foreign Policy. Ed. Kyung-Ae Park. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 78.

[90] Andrei N. Lankov, The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. 181.

[91] Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland, Famine in North Korea: Markets, Aid, and Reform. 219.

[92] Liu Ming, “Changes and Continuities in Pyongyang’s China Policy.” North Korea in Transition: Politics, Economy, and Society. Ed. Kyung-Ae Park and Scott Snyder. (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013), 222.

[93] For more, see: Kleine-Ahlbrandt, Stephanie, and Andrew Small. “China’s New Dictatorship Diplomacy. (Cover Story).” Foreign Affairs 87.1 (2008): 38-56. World History Collection. Web.

—

Written by: Curtis Bram

Written at: Tulane University

Written for: Dr. Martin Dimitrov

Date written: 2014

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- A Geostrategic Explanation of India-Myanmar Bilateral Relations since the 1990s

- North Korean Female Defectors in China: Human Trafficking and Exploitation

- Visceralities of the Border: Contemporary Border Regimes in a Globalised World

- Can China Continue to Rise Peacefully?

- China’s Take on Changing Global Space Governance: A Moral Realist Argument

- North Korea’s Withdrawal from the NPT: Neorealism and Selectorate Theory