On the evening of 17 December 2014, Sony Pictures announced that the company would not be releasing the highly anticipated political comedy The Interview on Christmas Day, as originally planned. [1] The film, which stars James Franco and Seth Rogen, hinges on a plot to assassinate North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. Within hours of announcement, senior administration officials within the U.S. government went on record claiming that the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was “centrally involved” in a cyberattack on the studio three weeks earlier: Pyongyang has consistently denied involvement in the hack. Since The Interview was first announced, the film has led to worsened relations between the United States and North Korea; however, in the wake of damaging infiltration into Sony Pictures’ network servers and subsequent release of sensitive documents, the situation has spiralled into a full-fledged international incident, including threats of terrorism directed at American movie-goers, concerns about the safety of kidnapped Japanese being held in North Korea, and louder calls for China to rein-in hackers operating from its soil. While certainly not the first Hollywood production to anger a foreign government, The Interview arguably represents the most controversial piece of popular culture to impact world politics in some time. This essay attempts to situate this film in what Kyle Grayson, Matt Davies, and Simon Philpott (2009) have labelled “the popular culture-world politics continuum” by looking back at similar controversies over the past decade, while also elucidating key elements of the protean nature of global affairs that will make such phenomena more common over the coming decades.

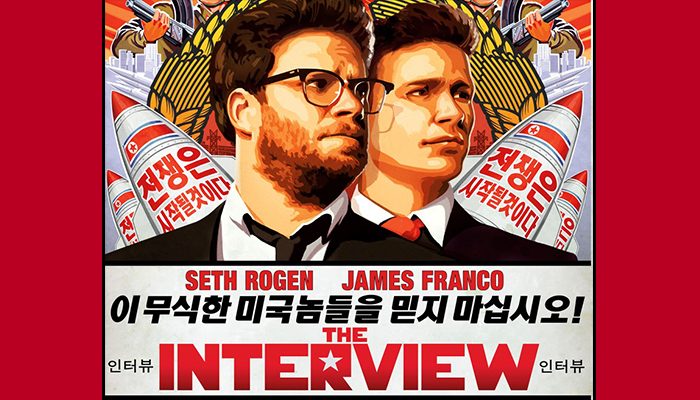

“Hollywood” as an Interlocutor in World Politics [2]

The controversy surrounding The Interview prompted a flurry of reportage (though with little depth or analysis) about Hollywood’s bumpy past with films featuring international themes. In his photo essay for the Daily News, Ethan Sacks listed a number of earlier American (and British) films that angered enemies of the United States, such as The Great Dictator (1940), From Russia with Love (1963), and Cry Freedom (1987). Writing in the New York Post, Reed Tucker also tackled the issue, but focused more on friendly states which were perturbed by their representations in big budget films, including the depiction of Slovaks as maniacal torturers in Eli Roth’s Hostel (2005) and Kazakhstan’s ire at its benighted rendering in Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006). Similar lists of Hollywood’s run-ins with overseas governments appeared on the web sites of NBC and The Daily Beast. In all these instances, filmmakers have trundled into the realm of world politics, provoking official and/or popular condemnation of their cultural products. In examining the long arc of Hollywood’s engagement with world politics, there is no shortage of analysis when it comes to the political ramifications of celluloid representation. In fact, many scholars attribute cinema with a powerful capacity to shape national identity (Edensor 2002; Dittmer 2005; Weber 2005; Philpott 2010), as well as being one of the most important inputs in determining attitudes towards the foreign Other (Sharp 1993; Ó Tuathail 1996; Weldes 2003; Shapiro 2008; Shepherd 2013). This is particularly true when it comes to the “enemy other,” whether it be Germans and Japanese (1940s), Soviets and Chinese (Cold War), or Islamist terrorists (1970s-today). Such outcomes are predictable, given the highly cooperative relationship between mainstream Hollywood studios and the American military-industrial complex since the late 1930s (Der Derian 2009; Alford 2010).

In the case of The Interview, which employs a sitting head of state as the antagonist, the xenophobic representational paradigm of an “Asiatic dictator” is overt, even reaching hyperbole to achieve comic effect; however, sculpting of the Other in film and other forms of popular culture is often more subtle (though nonetheless important in shaping political culture and attitudes to the outside world). No genre is completely free of such generalizations; for instance, Keith M. Booker (2010) points out that Disney animated classics are rife with Orientalism, anti-Germanism, and Russophobia. Correspondingly, Cold War-era science fiction films used metaphors to metastasize incipient fears of a Communist take-over, besmirching the national images of Russians, Eastern Europeans, and others in the process (Hendershot 2001). As the epitome of the spy-thriller genre, the James Bond franchise has “educated” generations of cinema-goers about the perils of world politics, from KGB assassins to African mercenaries to Latin American drug smugglers (Dodds 2003, 2005). In the wake of the 11 September 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Hollywood shifted into overdrive with a host of films addressing the “Global War on Terror,” further deepening the link between cultural production and world politics (Dodds 2008; Schopp and Hill 2009; Der Derian 2010) and perpetuating geopolitical codes and discourses (Crampton and Power 2005) that can be called upon by politicians at a moment’s notice.

During the 20th century, dozens of countries found something they did not like about the representation of their respective national images in American-made motion pictures. Yet, until quite recently, the relationship between Hollywood and foreign governments has been at arm’s length. The standard response to any negative portrayal was to ban the distribution of the film (sometimes fanned by a populist “boycott” of the film) and, in exceptional circumstances, to issue an official condemnation (often confusingly directed both at the filmmakers and their “host” governments, i.e. the White House or 10 Downing Street). However, in the new millennium, there has been a palpable shift, and one which more clearly reflects the importance of the popular culture-world politics continuum. Governments are now engaging in multivariate forms of negotiation with international publics, multinational corporations, and other transnational actors to negate or at least attenuate negative representation via moving pictures. Prior to The Interview, there were three high-profile cases of such quasi-diplomacy, with each reflecting different power dynamics on the world stage. [3]

Novel Geopolitical Responses to Pop-Culture: Borat (Kazakhstan), 300 (Iran), and Red Dawn (China)

Hyper-attuned to Western opinion, particularly that of economic elites in the U.S. and British fossil fuel industries, Kazakhstan’s refusal to countenance Sacha Baron Cohen’s parody of the Central Asian republic was not surprising (Saunders 2007). As early as 2000, embassy officials in the UK requested that then-prime minister Tony Blair “ban” Borat (at the time, Borat was simply a character on a minor British skit-comedy program The 11 O’Clock Show). However, as Baron Cohen’s star rose, the battle for the national image of Kazakhstan took on almost surreal proportions. Following an appearance by Baron Cohen on the 2005 MTV Europe Music Awards, Kazakhstan threatened to sue the British comedian and removed his web site from Kazakhstani servers. In 2006, as the premiere of the Borat film loomed, Kazakhstan changed tack, actively engaging in the farce in an effort to use the media blitz generated by Baron Cohen’s antics to educate a Western public that had suddenly become aware of the fact that Kazakhstan might actually be a real country. [4] Cheeky press interviews, YouTube videos, and calculated uses of the Borat meme to promote everything from fashion to architecture came to characterize Astana’s new attitude to the Cambridge-educated trickster (Saunders 2008). The end result: Kazakhstan became a known quantity, with tourism measurably increasing. Nearly a decade on, the shtick still lingers (and continues to sting a bit), but most Kazakhstanis now admit their country is better for the experience.

Whereas Kazakhstan represents one of the world’s newest countries, one of its oldest faced a similar situation (or at least perceived it to be so) one year later when Frank Miller’s epic graphic novel 300 (1998) was adapted for the big screen. Given the moral geopolitics of popular culture’s engagement with the Global War on Terror, as well as rampant rumours that the next Middle Eastern country the U.S. sought to invade was Iran, director Zack Snyder’s “monstrous othering” (Rai 2011) of the ancient Persians in the historical fantasy 300 did not go over well in Tehran. As Murat Es (2011) points out, 300 represents a genuine shift in Hollywood’s treatment of world geopolitics, in that it dispenses with Cold War-era trope equating the individualistic, thalassic, cerebral Athenians with the United States and the collectivist, land-bound, martial Spartans with Nazi Germany/USSR, eliding the two allies (both discernibly white and coded as European) together against a dark, bestial, semi-demonic Oriental enemy other (i.e., the Persians). Given the highly anti-Islamic, Orientalist content of the source material, populist responses to the film [5] – buttressed by secular and theocratic condemnation in Iran – came as no surprise to Iran experts in the foreign policy community. What proved to be most interesting was that the Iranian regime finally found common cause with the expatriate community, which took even greater umbrage due to the fact that most of the latter had identified as “Persians” since 1979 to avoid conflation with the former (an ethnic legerdemain that was fatally undermined by the film). While the Iranian government sought to rally other Muslim countries to a common cause against the Orientalist “Hollywood” assault on the Islamic East, Persian bloggers of all ideological stripes raged against the film, including engaging in “Google-bombing” whereby searches for 300 would redirect traffic to sites lauding Persian culture (Joneidi 2007).

Like Iran, China lays claim to an ancient and influential cultural patrimony; however, the country is also a fast-rising global power. Consequently, Chinese elites are highly attentive to their national image and its representation in international media. So when confronted with the prospect of a big-budget remake of the iconic 1984 anti-Communist action film Red Dawn, wherein China invades the U.S., Beijing used market pressures to facilitate a major change in the script (Landreth 2010). [6] Rather than a Chinese contingent, the occupying force was changed to – you guessed it – a squadron of North Korean paratroopers. With the growing size of its theatrical marketplace and limits on the number of foreign films that can be screened in a given year, China has developed massive leverage over mainstream Hollywood representations of its country, people, and culture. While in some cases, this means forcing studios into cutting “Chinese” villains from the plot, in other instances, studios are encouraged to add “positive” scenes depicting Chinese culture (Homewood 2014). Rather than taking the defensive posture of the Iranians or co-opting a fait accompli as the Kazakhstanis did, China brandishes its economic might to massage the media preventing “enemy images” of itself from seeing the light of day.

Deep Background on The Interview

Conceived by Seth Rogen and director Evan Goldberg more than five years ago, The Interview was originally slated to depict the assassination of the Kim Jong-il by a celebrity television journalist from the U.S.; however, upon Kim’s death in 2011, the project was shelved. Following the institution of the late leader’s son, Kim Jong-un, and the rather farcical series of events surrounding former professional basketball player Dennis Rodman’s unsanctioned diplomatic mission to North Korea in early 2013, Columbia Pictures greenlighted the film, with James Franco joining the cast and The Daily Show writer Dan Sterling taking over the screenplay. In June 2014, the film began to make headlines when North Korean government mouthpieces began issuing condemnations of the project (though not naming The Interview specifically) and its “gangster filmmakers,” calling it an “act of war” and emblematic of the “wanton acts of terrorism” the United States engages in the Middle East and elsewhere. North Korea promised a “merciless” response if and when the film premiered (McCurry 2014). Pyongyang then raised the issue with the United Nations’ Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, accusing the Obama Administration of sponsoring terror, and shortly thereafter entreating the White House to intervene to prevent the film’s then-scheduled October release.

Given the strange obsession that American cultural producers developed with the late megalomaniacal Kim Jong-un (Neild 2011), this is not the first time North Korea has been infuriated by Western popular culture. [7] In 2004, the satirical marionette action film Team America: World Police featured a climax in which U.S. special agents fight and kill Kim Jong-il only to discover he is not human, but a corporeal vessel containing an alien cockroach from the planet Gyron. After learning of this cinematic conceit, Pyongyang unsuccessfully petitioned the Czech government to ban the film’s release in the central European country. The following year, Pyongyang issued a strident condemnation of Western video games representing the regime as a military aggressor in the Pacific Rim, singling out Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon 2. A government newspaper issued the following ominous message directed at American game players: “This may be just a game to them now, but it will not be a game for them later. In war, they will only face miserable defeat and gruesome deaths” (qtd. in Brooke 2005). [8] In perhaps the most bizarre turn of events, North Korean diplomats complained to Britain’s Foreign Office in early 2014 about a poster by a London hairstylist which lampooned Kim Jong-un’s haircut, calling on the agency take “necessary action to stop the provocation” (diplomats also personally visited the salon to demand the advertisement’s removal from public view). With such a track record, the summertime rants against Seth Rogan and his L.A. clique were nothing out of the ordinary. In fact, it appeared that Pyongyang might even be inadvertently fuelling the marketing campaign for The Interview just as the Kazakhstani government had done with Borat prior to its about-face coinciding with the film’s premiere. All that changed on Monday, 24 November 2014.

That morning, employees of Sony Pictures Entertainment (the parent company of Columbia Pictures, the studio behind The Interview) encountered a disturbing skeletal image on their desktops notifying them of a network hack. The message stated that “This is just the beginning,” and that Sony must meet the (then-unspecified) demands of the “Guardians of Peace” (#GOP). [9] Initially, commentators assumed the cyberattack was comparatively minor, though the corporation shut down its computers for the days leading up to the Thanksgiving holiday; email accounts and phones were also offline. In the ensuing week, the hackers released four Sony films online, three of which had yet to be screened in theatres (the fourth, the Brad Pitt-starring Fury was already in cinemas). By Friday, the first links were made to North Korea, suggesting that the cyberattack was in response to the impending release of The Interview. One week after the initial intrusion, the hackers begin to release sensitive internal documents, including salaries of company executives; subsequent leaks would expose company in-fighting, scans of celebrity passports, scathing critiques of creative content, employee medical records, and hundreds of other pieces of confidential and embarrassing information. Ultimately, the Sony’s networks were rendered unusable, thus constituting what many have called the most physically damaging cyberattack in U.S. history. [10]

As the situation intensified, the FBI launched an investigation, thus elevating the political profile of the attack (on 19 December, the agency would publicly confirm North Korean culpability, a revelation that would be reiterated by U.S. President Barack Obama in his year-end press conference later that day); cyber-security experts begin to report “striking similarities” to earlier North Korean attacks on South Korean business concerns, despite Sony’s very public and repeated claims that the corporation rejected any connection to Pyongyang. On 5 December, #GOP attempted to force all employees to sign a condemnation of their employer or face unspecified threats.

Many things beyond imagination will happen at many places of the world. Our agents find themselves act in necessary places. Please sign your name to object the false of the company at the e-mail address below if you don’t want to suffer damage. If you don’t, not only you but your family will be in danger. (qtd. in Robb 2014)

Shortly thereafter, North Korea officially denied involvement, but praised the cyberattack as a “righteous deed.” On 15 December, former employees filed a class-action lawsuit against the studio for failing to safeguard their privacy. The following day, the hackers issue a veiled threat against Americans planning to view The Interview in theatres (the first mention of the film by name in a #GOP communiqué):

We will clearly show it to you at the very time and places The Interview be shown, including the premiere, how bitter fate those who seek fun in terror should be doomed to. Soon all the world will see what an awful movie Sony Pictures Entertainment has made. The world will be full of fear. Remember the 11th of September 2001. We recommend you to keep yourself distant from the places at that time. (qtd. in Robb 2014)

With this short statement, the cyberattack turned from industrial espionage/corporate blackmail into a national security threat, and one which specifically targeted American citizens. While U.S. Homeland Security was quick to dismiss the danger, the tenor of media reporting dramatically changed (curiously framed by the ongoing coverage of a lone-wolf jihadist terror attack on a Lindt café in downtown Sydney, Australia, an event which established the possibility of an attack on the most geopolitically “innocent” of locales). All press appearances for Franco and Rogen were cancelled, and on 17 December, eight days before the premiere, Sony announced that film had been pulled from theatrical release, a response to a decision on the part of the largest theatre chains in the U.S. refusing to screen The Interview (Barnes and Cieply 2014). Within hours, unnamed U.S. government officials formally laid the blame for the attack at the feet of Pyongyang (Sanger and Perlroth 2014).

North Korea Victorious?

At first blush, North Korea appeared to have emerged triumphant in this undeniable instance of popular culture and international relations clashing head-on. Having attempted to engage in classic statecraft to seek redress for the film’s (as-yet-unrealized) besmirching of its national image, Pyongyang’s pleas fell on deaf ears at the United Nations as well as the White House. Issuing calls for Columbia Pictures to stop the film also achieved nothing other than patronizing press coverage of the hermit state. However, when North Korean “cyber-warriors” [11] (and/or their proxies elsewhere) took direct action against Sony Pictures Entertainment and then threatened Americans with a 9/11-style terror attack, the film was pulled from theatrical release. The cyberattack and its aftereffects have sent ripples across the United States’ culture industries. In protest to the Sony capitulation and North Korea’s perceived complicity in the debacle, a number of theatres announced plans to show Team America: World Police in lieu of The Interview, so Christmas-day audiences would have a chance to see some satire in which a North Korean dictator dies at the end. However, such plans triggered a response from Paramount Pictures prohibiting any such screenings, ostensibly for fear of provoking a “terrorist” attack on these venues. The company has repeatedly declined to comment on its decision. More notably, actor Steve Carell announced that New Regency, a Fox-owned studio, had cancelled production on a thriller based on the Guy Delisle’s graphic novel Pyongyang (2004) in which Carell was to star.

In the realm of domestic and international politics, the full ramifications of the turn of events are still being realized. Perhaps the strongest statement so far came from former U.S. Republican representative and presidential candidate Newt Gingrich: “With the Sony collapse, America has lost its first cyberwar. This is a very very dangerous precedent” (qtd. in Britt 2014). The international importance of the event was underscored when Barack Obama, in a clearly calculated move, chose to dedicate a significant portion of his year-end press conference to the Sony controversy. In his unprepared remarks, he labelled Sony’s decision to pull the film a “mistake” (Obama 2014), suggesting that it set a dangerous precedent that would expose not only satirists, but also documentarians and news reporters, to future attempts at cyber-coercion, thus weakening the fabric of free speech in the country (and my implication, around the globe). He also assured the American people that the U.S. government would ultimately retaliate, given the clear link now established by the FBI:

They caused a lot of damage, and we will respond. We will respond proportionally, and we’ll respond in a place and time and manner that we choose. It’s not something that I will announce here today at a press conference. (Obama 2014)

The U.S. President went on tie the issue to larger questions of cybersecurity and elements of his international agenda:

More broadly, though, this points to the need for us to work with the international community to start setting up some very clear rules of the road in terms of how the Internet and cyber operates. Right now, it’s sort of the Wild West. And part of the problem is, is you’ve got weak states that can engage in these kinds of attacks, you’ve got non-state actors that can do enormous damage. That’s part of what makes this issue of cybersecurity so urgent. (Obama 2014)

Obama also announced that he had initiated discussions with Japan, China, South Korea, and Russia, seeking their assistance in reining in North Korea’s cyberterrorism capabilities (Holland and Spetalnick 2014). Despite the positive spin on China’s role as an ally in dealing with the threat, anonymous U.S. officials simultaneously raised the prospect that China (and perhaps Russia, as well) actually might be assisting North Korean agents in their efforts to infiltrate Western computer networks, based on recognizable technology signatures (Herridge 2014).

The same day as the presidential press conference, Homeland Security Chief Jeh Johnson, after making the rounds on the political talk show circuit, issued a statement following the FBI’s declaration of North Korean involvement:

The cyber attack against Sony Pictures Entertainment was not just an attack against a company and its employees. It was also an attack on our freedom of expression and way of life. This event underscores the importance of good cybersecurity practices to rapidly detect cyber intrusions and promote resilience throughout all of our networks. (Johnson 2014)

In the wake of the President’s condemnation of Sony’s actions, the company went into damage-control mode, denying that it had “caved” under pressure from the hackers. Sony, a Japanese multinational conglomerate, has consistently responded to the affair by urging restraint, concerned that publicly blaming the Kim regime for the cyberattack would endanger Japanese citizens who were abducted four decades ago by North Korean special forces (Tartaglione 2014), as well as complicate a variety of other bilateral and regional issues (already, Pyongyang has made statements about expanding the country’s nuclear capacity and refusing to accept the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity). Considering the historical closeness of large corporations to the Japanese government, it is not surprising that Sony chose to weigh the geopolitical impact of its cultural production and subsequent distribution practices. [12]

North Korea also responded to the President’s statements (characterizing these as “slander”), reiterating its innocence and offering to cooperate in a joint investigation to root out the real culprits. However, unnamed officials combined the offer with a threat, stating: “The U.S. should bear in mind that it will face serious consequences in case it rejects our proposal for joint investigation and presses for what it called countermeasures” (qtd. in Fackler 2014). Reflecting the country’s well-established (though often paradoxical) methods of international engagement, North Korea’s olive branch-cum-threat proved reminiscent of Cold War-era diplomacy, while also reminding the international community that we have entered a brave new world where popular culture, globalized capitalism, and shadowy cyber-warriors are determining, at least in part, the course of global affairs.

What Does This All Means for World Politics?

Scholars of international relations have generally proven to be somewhat uncomfortable in directly engaging with the effects of popular culture. Clearly, the preference of most realists and idealists would be to with more easily measured metrics, i.e. wars, treaties, alliances, etc. Even many of those researchers who identify as constructivists are still loath to admit that cultural production is an important part of how international relations is conceived (as well as how it “gets done”), instead placing it in the background where identities and interests are formed through “intersubjective practice” (Zehfuss 2003). [13] Yet an increasing number of IR theorists are willing to embrace Pierre Bourdieu’s simultaneously banal and radical claim that “when one is speaking of ‘popular culture,’ one is speaking about politics” (1978, 118). The discipline of popular geopolitics, pioneered by the likes of Jo Sharp, Klaus Dodds, and Jason Dittmer, has been a particularly fecund site for explaining the interconnections between pop-cultural representation and everyday conceptualizations of place and space. However, a critical mass of IR scholars, including Michael Shapiro, Jutta Weldes, Iver Neumann, and Cynthia Weber, have also pushed their peers in more traditional areas of research to grapple with the importance of popular culture on “real world” politics between, across, within, and beyond states. Thus far, the most cogent argument for why we should take the popular seriously has come from three scholars working together at Newcastle University. In their seminal essay, “Pop Goes IR? Researching the Popular Culture-World Politics Continuum,” these three researchers lay out the merits and pitfalls associated with such ground-breaking work:

Popular culture and world politics are often conceptualized within the discipline of international relations (IR) as potentially interconnected but ultimately separate domains. In part, this has been a reflection of the preference for IR to focus on the mechanisms, institutional arrangements, interests, bureaucracies and decision making processes that constitute relations among states, business and civil society actors. From this perspective, popular culture would be important in so far as it could be shown to have caused some kind of effect within these formal sites of activity. (Grayson, Davies, and Philpott 2009)

Had there been any doubt about the “measurability” of popular culture’s impact on international relations, the Sony cyberattack and the international imbroglio associated with The Interview has now put such concerns to rest.

As if a sitting U.S. president’s decision to spend the lion’s share of his year-end press conference on a satirical film was not enough to prove the existence of a popular culture-world politics continuum, we now see that the toilet-humor comedians Seth Rogen and James Franco are imbricated in the physical security of American movie-goers as well as abducted Japanese languishing in North Korea. It goes without saying that American (and Western) “identity” is thus being put on display in this collision of cultures; invidious references to Russia, China, and Iran and these countries’ attitudes towards “free speech” are just one part of this ideological-tinged representational theatre which hinges on binaries of good/evil, freedom/repression, open/closed societies, and us/them. Sony’s withering in the face of unrealistic threats has created an ideologically-charged space for politicians to engage in discursive practices reminiscent of the post-9/11 environment, whereby “freedom” and “our way of life” are presented as “under siege” from abroad. Moreover, the asymmetrical power dynamics between Washington and Pyongyang have come to the fore, requiring policy-makers and the news media commentariat to acknowledge the intricacies of post-Cold War international relations (and popular culture’s place within this constellation of action, reaction, perception, and misperception).

Moving beyond the West, it is not hyperbole to state that the Pacific Rim trembles as the year closes, worried about what an unpredictable, but tech-savvy, regime in Pyongyang will do next. Cyberterrorists are also likely to take note of the outcomes of Sony’s (perceived) surrender to the #GOP’s demands. William Pelfrey, Chair of the Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness program at Virginia Commonwealth University, commented on the situation:

This creates an interesting precedent of a company succumbing to a perceived (not realized) threat. [It] makes me wonder of other scenarios where a movement or organization could pressure a company to make changes through illicit means. Perhaps an environmental group pressuring an oil company to not drill/frack/pollute. Or attacking a Japanese company that kills whales. This sort of creates a whole new avenue for environmental terrorism. Stop doing what we dislike or we hack you. (Pelfrey 2014)

Lastly, while outside the realm of “hard” IR, Sony is now facing losses estimated $500 million (a figure that is likely to rise over time) due to unrealized income, as well as repairing and replacing its network infrastructure and fees associated with its cybersecurity investigation and spin doctoring. Relatedly – and perhaps most disturbingly for those interested in maintaining civil liberties and preserving the neutrality and accessibility of the Internet and all that it offers its users – this event is already being used a cudgel by politicians of all stripes (and the corporate lobbyists who represent large media concerns) to move on reforms that will restrict the freedom of the Web, all in the name of protecting us (i.e. freedom-loving Americans) from the dangers of the ‘outside world’.

As an “image superpower” (Frèches, qtd. in Morley and Robins 1995) engaged in a global conflict with any and all pretenders to the throne, the United States – with its film, television, video game, and new media industries – enjoys a massive capacity to create, perpetuate, and modify the national images of its friends and enemies alike. However, we also see from recent developments that other powers around the world now have tools at their disposal to “speak back” to the hegemon. Regardless, the U.S. government has made clear its intentions to protect its culture-generating assets, even those as sophomoric as the overgrown adolescents who brought us Pineapple Express (2008) and This Is the End (2013). This brings us to the key fundament of the “Pop Goes IR” argument, i.e. popular culture is on its way to becoming “the central future location of politics” (Grayson, Davies, and Philpott 2009). Consequently, IR scholars need to move beyond cause-and-effect relations between pop culture and world politics, and provide “insight into how these outcomes and the understandings of politics that underpin [are made] possible” (Grayson, Davies, and Philpott 2009). For those of us in the field of IR who spend as much of their time looking at films, video games, graphic novels, and television series as we do poring over government documents, military expenditures, diplomatic cables, and statistics from conflict zones, the furore surrounding The Interview provides a welcome fillip to our scholarly endeavours. However, it also raises some complicating questions about our discipline.

As Claire Groden and Elaine Teng (2014) point out in their timely essay in the New Republic, the controversy surrounding The Interview, as well as Western culture’s perpetual obsession with lampooning the Kim family, actually obscures genuine issues associated with the regime’s grotesque human rights abuses by allowing misplaced fears of a Yellow Peril, combined with Orientalist feminization and infantilization of Asian men, to occupy the political space where proper condemnation should occur. They also argue that the U.S. government’s readiness to take on the North Koreans during the same week that relations with Cuba were being normalized (with the hope of opening up new markets in the Caribbean nation) reflects a highly calculated effort at extending the nearly complete victory of capitalism over communism, given that now “North Korea is the only Cold War vestige left” on the international stage (Groden and Teng 2014). Such analysis reminds IR scholars of the importance of Hollywood as an appendage of U.S. foreign policy as the Pentagon’s principal enemy-image factory, a machine that is engaged in the production and re-production revanchist Russians, Arab terrorists, Latin American drug lords, and – in the case at hand – “Oriental dictators,” just like Ford’s assembly line rolled-off Model Ts. With this constant cinematic construction of Others (abetted by first-person shooter video games, an infotainment-based news media, and other profit-centric “industries” of Othering), understanding the popular culture-world politics continuum is key, as is elucidating the market dynamics of enemy representation and how this influences the conduct of foreign policy. [14] Likewise, developing novel methodologies and theoretical approaches for dealing with the changing dynamics of international power relations is also imperative; this is a particularly acute concern for IR scholars as complex economic interdependence deepens and expands, rooting additional state and non-state actors in the chaotic realm of popular geopolitics.

Yet, the vehemence with which North Korea has taken up its own defence against the tender mercies of Hollywood prompts other conceptual and theoretical concerns. Will the trends set by Kazakhstan, Iran, China, and other media-sensitive states continue and morph as the world’s shared media space grows? What can we expect in the future if Russia decides it has grown tired of being the baddie? The country’s proven capacity for (proxy) net-war was clearly established in the Estonian cyber-attacks of 2007 – will the next James Bond film be a showcase for Russia’s burgeoning cyber-power? What if, in some instance, China cannot use its market presence to stanch negative images of its people and culture in the future – will Beijing resort to coercive forms of online activism (in recent years, pro-Chinese hackers have already made their presence felt regarding questions of patriotism and national identity across Southeast Asia and elsewhere)? It is even possible that countries like Brazil or India may choose to follow in the path of North Korea, using novel tools and techniques to extinguish negative representations of national identity on the silver screen. If any of these scenarios do come to pass, we as scholars of IR should be thankful that a few intrepid scholars have already provided us with the analytical scaffolding to address these prickly issues. All hail the popular culture-world politics continuum!

My sincere thanks to Federica Caso for her thoughtful critique of this essay in draft form, as well for suggesting a variety of further geopolitical implications of the controversy, especially those related to Internet freedoms, ideology, and the economic dynamics of enemy-image production.

Notes

[1] At the time of writing, it was unclear if the motion picture would ever be screened in cinemas. However, following U.S. President Barack Obama’s sharply worded critique of its actions in choosing not to distribute The Interview to those movie theatres willing to show it, Sony Entertainment CEO Michael Lynton declared his intention to find some way to release the film. BitTorrent has offered to assist Sony in releasing the film online, which in combination with PayGate would allow for individual users to pay for viewing the film. The offer was greeted with a less-than-enthusiastic response by content providers due to BitTorrent’s standing as a major source of pirated material via peer-to-peer file sharing.

[2] Intentionally reflecting the conceptual sloppiness of journalistic shorthand, I use the term “Hollywood” in quotes to stand in for mainstream popular cultural production associated with the Anglophone west.

[3] Quasi-diplomacy here refers to forms of transborder political interaction conducted outside the traditional structures and institutions of post-Westphalian interstate relations; however, like traditional definitions of diplomacy, I recognize that quasi-diplomacy is a multidimensional and relational concept dependent on identifying the “self” and the “other” (see Carta 2013).

[4] Despite playing along in the West, Kazakhstan, in the end, did not allow the film to be shown in its theatres. Russia and a number of other “sympathetic” countries also effectively banned the motion picture.

[5] Frank Miller unabashedly declares his antipathy towards Islamism and emerged as a pop-culture firebrand in to the wake of 9/11. His attempts to transform the iconic superhero Batman into an anti-Muslim vigilante was rejected by DC Comics as too controversial for the imprint. Miller ultimately created another character (The Fixer) to achieve these ends; the hardcover graphic novel Holy Terror (2011) was published by Legendary Comics (see Ackerman 2011).

[6] When details of the script were leaked in 2010, one of China’s leading state-run newspapers, The Global Times, indicted the film as a “demonization” of China.

[7] North Korean condemnations of South Korean popular culture are even more strident. However, in recent years, Pyongyang has come to understand how deeply embedded southern pop culture has become in the north, adapting to these realities and even using parodies of popular South Korean memes to critique their southern neighbor.

[8] Other Western video games posting the North Korean military as the primary enemy include Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory by Ubisoft (2005); Mercenaries: Playground of Destruction by LucasArts (2005); Crysis by Crytek (2007); and Homefront by Kaos Studios (2011). Interestingly, the Atlanta, Georgia-based developer MoneyHorse games recently announced its release of “retro style run ‘n’ gun” game entitled Glorious Leader! depicting Kim Jong-un single-handedly taking on the U.S. military, including gameplay where he sits atop a narwhale (see Shearlaw 2014).

[9] George Clooney, who injected himself into the controversy by trying to get Hollywood executives and prominent actors to sign a petition in support of The Interview (no one he asked would agree to sign), has made the claim that the nomenclature of the group reflects hoary Cold War grudges. In an interview with Deadline | Hollywood, the actor stated: “The Guardians of Peace is a phrase that Nixon used when he visited China. When asked why he was helping South Korea, he said it was because we are the Guardians of Peace” (Fleming 2014).

[10] The destructive nature of the cyberattack has parallels in only three other events: the Operation Olympic Games attack on Iranian nuclear facilities (2006-2012); the malware attack on Saudi Aramco (2012); and the “DarkSeoul” cyber-warfare campaign against South Korean corporations. In all cases, a state actor was purported to be behind each of these attacks, i.e. the United States, Iran, and North Korea, respectively (see Sanger 2014).

[11] According to some experts, the attack is likely to have originated in North Korea’s Bureau 121 (also known as the “DarkSeoul Gang”), a military unit comprised of highly trained computer warfare experts (see Park and Pearson 2014).

[12] Before cancelling the film’s distribution in the U.S., Sony had already decided against a theatrical release in Asia, fearing the film might jeopardize sensitive regional geopolitical issues or enflame nationalist passions on the Korean peninsula.

[13] Certainly, the more radical constructivists would not fall into this category, given their profound interest in discourse.

[14] Borrowing from David Campbell (1998), we might refer to this as how “villains” are written into the script of U.S. foreign policy via popular culture (films, video games, TV series, comic books, Internet memes, etc.), and how American national identity tropes and geopolitical codes are situated and mobilized to ensure these enemy frame “stick.”

Sources

Ackerman, Spencer. 2011. Frank Miller’s Holy Terror Is Fodder for Anti-Islam Set. Wired, available at http://www.wired.com/2011/09/holy-terror-frank-miller/ [last accessed 18 December 2014].

Alford, Matthew. 2010. Reel Power: Hollywood Cinema and American Supremacy. New York: Pluto Press.

Barnes, Brooks, and Michael Cieply. 2014. Sony Drops ‘The Interview’ Following Terrorist Threats. New York Times, available at http://mobile.nytimes.com/2014/12/18/business/sony-the-interview-threats.html?emc=edit_na_20141217&nlid=46122742&_r=1&referrer [last accessed 19 December 2014].

Booker, Keith M. 2010. Disney, Pixar, and the Hidden Messages of Children’s Films. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1978. La sociologie de la culture populaire. In Le Handicap socioculturel en question. Paris: ESF.

Britt, Russ. 2014. North Korea Brokers Peace between Republicans and Democrats. Market Watch, available at http://www.marketwatch.com/story/strange-bedfellows-show-up-in-sony-hacking-2014-12-18 [last accessed 20 December 2014].

Brooke, James. 2005. Pop Culture Takes Aim at North Korea’s Kim. New York Times, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2005/06/01/world/asia/01iht-north-5079850.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 [last accessed 19 December 2014].

Campbell, David. 1998. Writing Security: United States Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Carta, Caterina. 2013. The European Union Diplomatic Service: Ideas, Preferences and Identities. London: Routledge.

Crampton, Andrew, and Marcus Power. 2005. Reel Geopolitics: Cinemato-graphing Political Space. Geopolitics 10:193-203.

Der Derian, James. 2009. Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network. London: Routledge.

———. 2010. Imagining Terror: Logos, Pathos, and Ethos. In Observant States: Geopolitics and Visual Culture, edited by F. MacDonald, R. Hughes and K. Dodds. London and New York: I. B. Tauris.

Dittmer, Jason. 2005. Captain America’s Empire: Reflections on Identity, Popular Culture, and Post-9/11 Geopolitics. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95 (3):626-643.

Dodds, Klaus. 2003. License to Stereotype: Popular Geopolitics, James Bond and the Spectre of Balkanism. Geopolitics 8 (2):125-156.

———. 2005. Screening Geopolitics: James Bond and the Early Cold War Films (1962–1967). Geopolitics 10: 266-289.

———. 2008. Hollywood and the Popular Geopolitics of the War on Terror. Third World Quarterly 29 (8):1621-1637.

Edensor, Tim. 2002. National Identity, Popular Culture and Everyday Life. Oxford: Berg.

Es, Murat. 2011. Frank Miller’s 300: Civilization Exclusivism and the Spatialized Politics of Spectatorship. Aether: The Journal of Media Geography 8 (2):6-39.

Fackler, Martin. 2014. North Korea Warns U.S. Not to Take Sony Action. New York Times, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/21/world/asia/north-korea-denying-sony-attack-proposes-joint-investigation-with-us.html [last accessed 20 December 2014].

Fleming, Mike. 2014. Hollywood Cowardice: George Clooney Explains Why Sony Stood Alone In North Korean Cyberterror Attack. Deadline | Hollywood, available at https://deadline.com/2014/12/george-clooney-sony-hollywood-cowardice-north-korea-cyberattack-petition-1201329988/ [last accessed 20 December 2014].

Grayson, Kyle, Matt Davies, and Simon Philpott. 2009. Pop Goes IR? Researching the Popular Culture-World Politics Continuum. Politics 29 (3):155-163.

Groden, Claire, and Elaine Teng. 2014. Stop Making Fun of North Korea: Our Laughter is Drowning Out Their Horrific Human Rights Record. New Republic, available at http://www.newrepublic.com/article/120599/interview-sony-hack-obscures-north-korea-human-rights-abuses [last accessed 20 December 2014].

Hendershot, Cynthia. 2001. I Was a Cold War Monster: Horror Films, Eroticism, and the Cold War Imagination. Madison, WI: Popular Press.

Herridge, Catherine. 2014. Evidence in Sony Hack Attack Suggests Possible Involvement by Iran, China or Russia, Intel Source Says. Fox News, available at http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2014/12/19/fbi-points-digital-finger-at-north-korea-for-sony-hacking-attack-formal/ [last accessed 20 December 2014].

Holland, Steve, and Matt Spetalnick. 2014. Obama Vows U.S. Response to North Korea over Sony Cyber Attack. Reuters, available at http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/12/19/us-sony-cybersecurity-usa-idUSKBN0JX1MH20141219 [last accessed 20 December 2014].

Homewood, Chris. 2014. Hollywood, Orientalism, and Chinese Soft Power. In Situating the Popular in World Cinemas. University of Leeds.

Johnson, Jeh. 2014. Statement By Secretary Johnson On Cyber Attack On Sony Pictures Entertainment. Department of Homeland Security, available at http://www.dhs.gov/news/2014/12/19/statement-secretary-johnson-cyber-attack-sony-pictures-entertainment [last accessed 20 December 2014].

Joneidi, Majid. 2007. Iranian Anger at Hollywood ‘Assault’. BBC News, available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/6455969.stm [last accessed 18 December 2014].

Landreth, Jonathan. 2010. Chinese Press Rails against ‘Red Dawn’. Hollywood Reporter, available at http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/chinese-press-rails-red-dawn-24152 [last accessed 19 December 2014].

McCurry, Justin. 2014. North Korea Threatens ‘Merciless’ Response over Seth Rogen Film. The Guardian, available at http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/25/north-korea-merciless-response-us-kim-jong-un-film [last accessed 19 December 2014].

Morley, David, and Kevin Robins. 1995. Spaces of Identity: Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries. London and New York: Routledge.

Neild, Barry. 2011. Kim Jong Il’s Bizarre Life as a Pop Culture Icon. CNN, available at http://www.cnn.com/2011/12/19/world/asia/north-korea-leader-culture/ [last accessed 19 December 2014].

Ó Tuathail, Gearóid. 1996. Critical Geopolitics: The Politics of Writing Global Space. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Obama, Barack. 2014. President Obama’s Year-End Press Conference. White House, available at http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/texttrans/2014/12/20141219312317.html#axzz3MSpzo686 [last accessed 20 December 2014].

Park, Ju-min, and James Pearson. 2014. In North Korea, Hackers are a Handpicked, Pampered Elite. Reuters, available at http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/12/05/us-sony-cybersecurity-northkorea-idUSKCN0JJ08B20141205 [last accessed 20 December 2014].

Pelfrey, William. 2014. Interview with the author, 18 December.

Philpott, Simon. 2010. Is Anyone Watching? War, Cinema and Bearing Witness. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 23 (2):325-348.

Rai, Shailza. 2011. Identity and its Monsters: Borders Within and Without. In Cartographies of Affect: Across Borders in South Asia and the Americas, edited by D. A. Castillo and K. Panjabi. Delhi: Worldview Publications.

Robb, David. 2014. Sony Hack: A Timeline. Deadline | Hollywood, available at http://deadline.com/2014/12/sony-hack-timeline-any-pascal-the-interview-north-korea-1201325501/ [last accessed 19 December 2014].

Sanger, David E. 2014. Interview on Up With Steve Kornacki, ‘President Obama Vows US Response to Sony Attack’. MSNBC, available at http://www.msnbc.com/up/watch/president-obama-vows-us-response-to-sony-attack-375472707838 [last accessed 20 December 2014].

Sanger, David E., and Nicole Perlroth. 2014. U.S. Said to Find North Korea Ordered Cyberattack on Sony. New York Times, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/18/world/asia/us-links-north-korea-to-sony-hacking.html?emc=edit_na_20141217&nlid=46122742&_r=0 [last accessed 19 December 2014].

Saunders, Robert A. 2007. In Defence of Kazakshilik: Kazakhstan’s War on Sacha Baron Cohen. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 14 (3):225-255.

———. 2008. Buying into Brand Borat: Kazakhstan’s Cautious Embrace of Its Unwanted ‘Son,’. Slavic Review 67 (1):63-80.

Schopp, Andrew, and Matthew B. Hill, eds. 2009. The War on Terror and American Popular Culture: September 11 and Beyond. Madison and Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson Press.

Shapiro, Michael J. 2008. Cinematic Geopolitics. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis.

Sharp, Joanne P. 1993. Publishing American Identity: Popular Geopolitics, Myth and The Reader’s Digest. Political Geography 12 (6):491-503.

Shearlaw, Maeve. 2011. Glorious Leader! US Developers to Launch North Korea, the Video Game. The Guardian, available at http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/14/glorious-leader-us-developers-to-launch-north-korea-the-video-game [last accessed 19 December 2014].

Shepherd, Laura J. 2013. Gender, Violence and Popular Culture: Telling Stories. London and New York: Routledge.

Tartaglione, Nancy. 2014. Japan-North Korea Talks Seen Unaffected By Sony Hack Attack Revelations. Deadline | Hollywood, available at https://deadline.com/2014/12/japan-north-korea-talks-sony-hack-kidnapping-1201329188/ [last accessed 20 December 2014].

Weber, Cynthia. 2005. Imagining America at War: Morality, Politics and Film. London and New York: Routledge.

Weldes, Jutta, ed. 2003. To Seek Out New Worlds: Exploring Links between Science Fiction and World Politics. Houndsmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Zehfuss, Maja. 2003. Constructivism in International Relations: The Politics of Reality. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Future of Popular Geopolitics: Mega-Shark Cinematic Diplomacy

- Opinion – North Korea’s Nuclear Tests and Potential Human Rights Violations

- The Diplomat: Gender and Security in Popular Culture

- Plotting the Future of Popular Geopolitics: An Introduction

- Punk AF: Resisting Postmodern Interpretations of Punk Culture in World Politics

- Future of Popular Geopolitics: Croatia, Affective Nationalism and the World Cup