In recent years, many observers of international politics tend to perceive Turkish foreign policy as increasingly moving away from its pro-Western orientation (Keyman, 2013; Kirisci, 2006; Muftuler-Bac, 2011). This is surprising given the extensive political, economic and military ties Turkey has with the USA and its European allies since the end of World War II. Turkey’s membership in NATO since 1952 – much before traditional European powers such as West Germany or Spain, its role as a founding member of the Council of Europe in 1949 – again before Spain, Portugal, and the Central and Eastern European states became members to that organization, and its integration into the European Union first with an Association Agreement in 1963, later on as a candidate country for accession, portray a picture where Turkey is irrevocably part of the European order. The institutional ties Turkey has with the European order are extensive and in many cases irreversible. In addition, its military and economic capabilities reflect a country with an ability to exert significant influence on the region it is located in (Muftuler-Bac, 2014). Given Turkey’s role in NATO and its potential membership in the EU, Turkey’s foreign policy in the Middle East has the capacity to impact both global dynamics and the European role in the region.

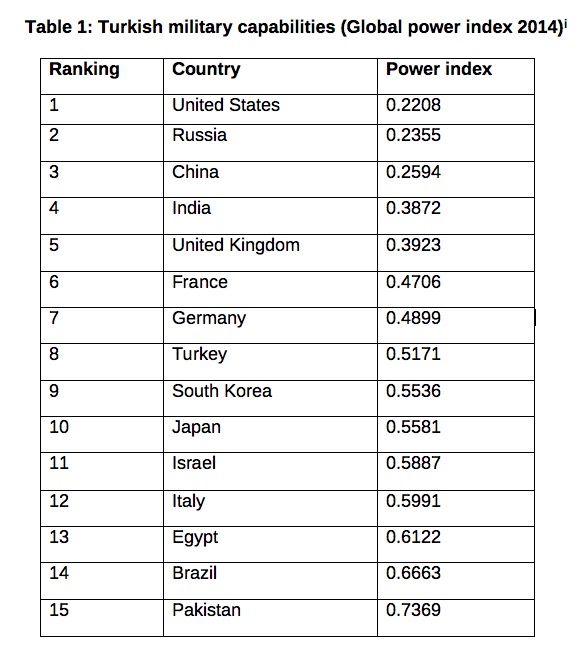

Turkey’s geostrategic position and its historical and cultural ties with its neighbors carry great potential to transform Turkey into a lynchpin in world affairs. This is particularly important in the currently highly turbulent period of international relations, specifically with the increased uncertainty in the region Turkey is located in. Given its geostrategic location, historical institutional ties with the Western and Middle Eastern countries, military and economic capabilities, one would have expected to see Turkey to assume a leadership role and a more proactive foreign policy. Yet, in recent years, Turkey’s foreign policy is increasingly ridden with multiple failures. To give some concrete examples, Turkey has no diplomatic relations with Israel – a one-time close friend and ally in the 1990s, with Syria or with Egypt. Its relations with Iran and Iraq are rocky, its European Union accession negotiations – ongoing since 2005 – are slowly coming to a halt and its most reliable ally, the USA, seems to have serious misgivings about their relationship. Even Turkey’s seemingly stable relations with the Gulf countries are deteriorating. There are, of course, other factors at play here that complicate Turkey’s relations with these countries and groups of states, so the main reason for this turbulence is not solely due to Turkey’s own foreign policy choices. Given Turkey’s ranking in the global power calculations as seen in Table 1, a higher degree of involvement in international affairs would have been expected.

It is not only the current ranking that is significant for us to assess Turkey’s global standing, but also its military spending which is substantial with 19.1 billion dollars in 2014 placing Turkey as the 14th highest spender globally in military expenditures. However, sheer military power is insufficient for Turkey to become a regional player as this needs to be bolstered by both economic and political clout. This seems to be where the gap between Turkey’s capabilities and its ability to influence regional and global politics lie. So what are the main obstacles Turkey faces in its foreign policy in the recent years? In particular, why did Turkey with all the capabilities at its disposal did not become a more effective player in regional and global politics?

Turkey’s choice

An important cornerstone of Turkey’s foreign policy outlook is its relations with the European Union. Turkey formulated its foreign policy objectives to become a member of the then European Community as early as 1959, two years after the Rome Treaty was signed. It negotiated an Association Agreement in 1963, a Customs Union Agreement in 1995, became an official candidate for EU accession in 1999 and began its accession negotiations in 2005. Despite a high level of commitment to EU political norms and criteria up until 2008, Turkey drifted away from its EU membership objective. An important factor leading to this divergence was the mixed signals coming from the EU: The EU suspended negotiations for 8 chapters at the end of 2006 due to the Turkish non-implementation of the Additional Protocol on the Customs Union to Cyprus. EU members such as France and Cyprus vetoed opening of chapters where the Turkish ability to meet the EU’s opening bench marks were largely met. The internal problems within the EU both towards further enlargement and towards Turkey’s accession in particular were reflected onto Turkey, leading to a loss of credibility for the negotiations process. Yet, Turkey’s own commitment to the EU process was also questionable as it moved away from the EU norms of liberal democracy, and adopted measures curtailing various freedoms. As the Turkish-EU relations deteriorated and accession negotiations stalled, Turkey moved away from Europe. However, Turkey’s European orientation is a critical anchor for Turkish political transformation and its democratic consolidation. The weakening of this anchor does not bode well for the future of Turkish-European relations, and also for Turkish democracy.

To give a sense of the deterioration in the Turkish democratic standards in the last five years, a quick look at various democracy rankings from Freedom House, to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index to the Freedom of Press Index and the World Gender Gap report seems to be sufficient. For example, in 2014, Turkey ranked 154th place out of 180 countries in the Freedom of Press rankings.[ii] Similarly, the Freedom House reports on Turkey lists the country as partly free, and Turkey ranks as 125th out of 140 countries in the 2014 Gender Gap Index[iii]. In all of these rankings, one is able to see a worsening of the democratic situation increasingly after 2011. This democratic deterioration is then reflected onto Turkey’s relations with Europe, but also its relative role in the Middle East region.

While Turkey increasingly moved away from Europe, its relations with its Middle Eastern neighbors went through similar ups and downs. Up until 2010, Turkey’s relations with its Arab neighbors blossomed. It adopted soft power tools of diplomatic engagement with all these countries, expanded its economic ties – both through trade and foreign direct investment, increased social interactions between Turkey and the Arab countries through tourism as well as the export of Turkish soap operas. However, the developments in the Arab world after 2010 came as an unexpected shock for Turkish foreign policy. The Arab Spring constituted a serious test for Turkey’s foreign policy of “zero problems” which more-or-less defined Turkish foreign policy since 2007 where the main objective was to eliminate all sources of tension with its neighbors, in particular the Middle Eastern ones.

The process of socio-political transformation in the Middle East since 2010 led to the collapse of authoritarian governments. Specifically, the old regimes in the Arab world found themselves confronted with demands of justice, freedom and democracy. The common denominator for all is that there seems to be a societal demand for increased political participation and basic liberties (Bellin, 2012). Despite its commitment to promoting democracy in its periphery, the European Union’s role in Arab spring has been largely ineffective (Hollis, 2012). As a result, Turkey had a prime opportunity to act as a regional actor promoting both democratic consolidation in the region and the transformation process in the Arab spring countries. This was partly because Turkey was perceived to be a democratic and secular country with a predominantly Muslim society, integrated into the European order and where there is a cohabitation of Islamic values together with Western life styles. These unique attributes of the Turkish political order have been perplexing for Turkey’s neighbors, but also for Western Europe. In the Arab world, there is a close monitoring of developments in Turkey, most notably by “liberal, secular and reformist groups … who see a possible way out from their own dilemma” (Benli Altunisik, 2008: 48). However, Turkey’s own democratic problems were reflected in its relations with the Middle Eastern countries. The once looked upon Turkish model of reconciling democratic norms with Islamic values lost its appeal as the Turkish democracy deteriorated. This is why the Arab Spring turned out to be a missed opportunity for Turkish foreign policy.

Conclusion

Turkey has always occupied a critical position in regional and global balances. Its geostrategic position, crude capabilities, historical and institutional ties in the international global governance structures constitute the basis for that position. However, the country seems to be facing an increased alienation in global affairs as its relations with traditional allies in the West as well as its newly established close relations with the Middle Eastern states go through various ups and downs. Turkey’s own democratic consolidation problems turned out to pose limitations on its ability to project power in the region, and widened the chasm with the European Union. Foreign Policy begins at home. In order to have a greater say in the world, Turkey needs to take a quantum leap towards liberal democracy. This seems to be most important challenge Turkish foreign policy currently faces.

Notes

[i] Global Firepower calculations (2014), http://www.globalfirepower.com.

[ii] Reporters without borders, Freedom of Press index, 2014, http://rsf.org/index2014/en-index2014.php

[iii] Gender Gap Report 2014.World Economic Forum. http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2014/economies/#economy=TUR

References

Bellin, Eva (2012). ”Reconsidering the robustness of authoritarianism in the Middle East: Lessons from the Arab spring”, Comparative Politics, 44 (2), 127-149.

Benli Altunisik, Meliha (2008) “The Possibilities and Limits of Turkey’s Soft Power in the Middle East”, Insight Turkey, 10 (2), 41-54.

Fontaine, R. and Kliman, D. (2013) ‘International Order and Global Swing States’, The Washington Quarterly, 36 (1), 93-109.

Hollis, Rosemary (2012) “No friend of Democratization: Europe’s role in the Arab Spring”, International Affairs, 88 (1), 81-94.

Keyman, Fuat (2013) Turkey’s Transformation and Democratic Consolidation, Pelgrave/Macmillan, London.

Kirişçi, Kemal (2006) “Turkey’s Foreign Policy in Turbulent Times,” Chaillot Paper, No. 92.

Müftüler-Baç, Meltem (2011) “Turkish Foreign Policy Change, its Domestic Determinants and the Role of the European Union”, South East European Politics and Society, 16 (2), 279-291.

Meltem Muftuler-Bac, (2014) Turkey as an Emerging Power: An analysis of its Role in Global and Regional Security Governance Constellations, Robert Schuman EUI.RSCAS paper 2014/52.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Turkish Foreign Policy after the 2023 Elections

- Turkey’s Role in Syria: A Prototype of its Regional Policy in the Middle East

- Deciphering Erdoğan’s Foreign Policy after Turkey’s 2023 Elections

- Opinion – Spain’s Request For NATO Coronavirus Aid: Will Turkey Answer?

- Opinion – NATO’s Expansion in Northern Europe Rests on Türkiye

- The Fragility of Turkish Democracy