This is an excerpt from Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives – an E-IR Edited Collection. Available now on Amazon (UK, USA, Fra, Ger, Ca), in all good book stores, and via a free PDF download.

Find out more about E-IR’s range of open access books here.

In the title of the article, I have reproduced the topic proposed by the editors of the collection, however, I consider the stylistic formula ‘Russians in Ukraine’ to be rather confusing and unable to grasp the essence of the problem. The idea of Russians in Ukraine being a national minority similar to, for instance, Hungarians in Romania or Slovakia, Swedes in Finland, or even Russians in Estonia, is in fact profoundly fallacious. And not because of the scope of inclusion – I will talk about that later. But it is this idea that underlies western policies towards Ukraine and the current crisis. According to that idea, the Ukrainians, with the moral support of the West, are trying to free themselves from the centuries-old Russian colonial oppression, while Moscow resists it in every way, and as soon as it ‘lets Ukraine go’, European values will triumph in Ukraine.

Before the crisis, the inadequacy of the European perception of the Ukrainian reality was more or less harmless. Except that it was gradually smoothing the way for ‘inevitability’ of the choice between Russia and Europe – naturally, in favour of ‘the European choice’. During the crisis, such an approach has led to encouraging the inflexibility of the position of the Kiev government that came to power riding the wave of the Maidan, and that in turn has contributed to the loss of Crimea and to the civil war in the South-East.

Russians in Ukraine do not represent such a distinctive national group as other large minorities in other countries. The thing is that both contemporary Russians and Ukrainians (at least, inhabitants of the lands of the former Russian Empire, that is the majority of contemporary Ukraine) originate from the people of common (All-Russian, ‘Orthodox’) identity, where the differences between Great Russians (‘Russians’) and Little Russians (‘Ukrainians’) were rather of regional or sub-ethnic nature. I think that it would be more correct to consider Russians, alongside Ukrainians, to be a state-constituting nation of Ukraine within its 2013 borders, and not a national minority. It is worth noting that almost half of ethnic Ukrainians prefer to speak Russian in private life.

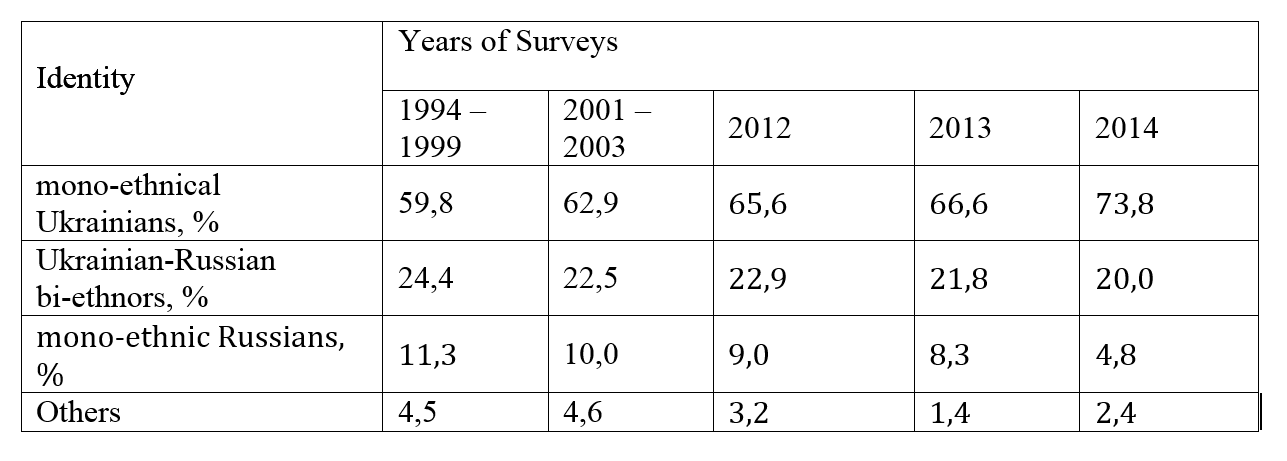

In order to provide an adequate description of the ethnic structure of the population of Ukraine, Ukrainian sociologist Valeriy Khmelko introduced the concept of ‘bi-ethnors’, i.e. people with ‘double’ Ukrainian-Russian identity (Khmelko, 2004). Representative surveys of the population of Ukraine carried out during the last 20 years are summarised in this table:

As can be seen from the table, the share of mono-ethnic Ukrainians has increased by 10%, compared to the first survey, and the proportion of bi-ethnors has decreased, similarly to the number of mono-ethnical Russians, which is down by almost 30%. 2014 numbers are quite predictable due to the loss of Crimea, where the population is mostly Russian. Since Ukrainian civil identity has been shaped not only by ethnic Ukrainians, it is important to ask what has played a decisive role in the formation of Ukrainian civil identity. As Ukrainian researcher Aleksey Popov argues, it was the creation of the USSR with the quasi-statehood of its union republics. In the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Russian-speaking population started to identify themselves with Ukraine (Ukrainian SSR) – ‘we live in Ukraine, so we are Ukrainian citizens, “Ukrainians.”’ It was particularly facilitated by the linguistic proximity of the Russian and Ukrainian languages, and had led to the fact that despite mixed population (Russian and Ukrainian speaking), there was no division into national communities, as was the case in the Baltic republics, in Transcaucasia, in Central Asia, and in the Russian autonomous republics of Caucasia. Partly because of the total absence of any conflicts between Russians and Ukrainians on the domestic level, the establishment of an independent Ukraine in 1991 was achieved practically seamlessly.

However, that lack of manifestation of the Russian element in Ukraine had its limits. Many Russians, and Ukrainians who identify with Russian culture and language, voted for Ukrainian independence from Russia, but did not support Ukraine’s exit from Russia’s sphere in favor of Western Europe. Similarly, support for independence did not mean support for a gradual ousting of Russian language – a tendency that at the time was only of a declarative sort. Moreover, the citizens clearly did not foresee that dramatic decline in the living standards. Russians and the Russian-speaking population above all have responded to the situation with a strong desire for closer ties with Russia and for the state status of Russian language, which found its expression during the presidential election of 1994. Ever since, practically every election has registered the splitting of the country into two Ukraines: the absolute majority of the Russian-speaking population voted for one presidential candidate, and the absolute majority of the Ukrainian-speaking population for their opponent.

At the same time, the Russian element in Ukraine does not represent a unified force. Russians do not have an influential party of their own, although the presence of such ethnic parties is an integral feature of other European countries. Belgium, for instance, is divided into parties by ethnic markers (Flemish and Walloon); Hungarians in Romania, Slovakia and Serbia; Albanians in Macedonia and Montenegro; Swedes in Finland; the peoples of Spain (the Basques, the Catalonians, the Galicians, etc.) – all of them have their own parliamentary parties. Therefore, one can often unmistakably count how many votes a national party would get – for the noted Hungarians, Swedes, and Albanians, that number corresponds to their share in the total number of voters in their country. In Spain or, for example, in Great Britain, with its Scottish and Welsh nationalists, such results fluctuate noticeably, thus apparently reflecting ethnic proximity as well.

In Ukraine, however, there have only been substitutes for Russian parties – such as the Communist Party (CPU) or the Party of Regions (PoR). Some of them, such as the CPU, reflected not so much the Russian but Soviet identity. Others – the PoR, tried to present themselves as representatives of industrial South-East, while forgetting their declarations after coming to power and ignoring the interests of their supporters.

The type of Ukrainian identity that has developed over years, and which has been shared by Russians and representatives of national minorities, can be referred to as a ‘civil identity’. Importantly, the Ukrainian ‘civil identity’ was not anti-Russian and it presupposed sympathies toward Russia and Russian culture, therefore it was acceptable for Russians in Ukraine. Importantly, the devotion to this identity has been shared until recently by the absolute majority of the citizens of our country.

However, along with ‘civil identity’, another identity type has played a significant role in the events of the end of 2013 and 2014, namely ‘political identity’. It presumes adherence to a certain assortment of political positions and it defines the community of people united by: a) the Ukrainian language, b) hatred for ‘colonial’ past in the USSR/Russia, c) memory of the 1932-1933 Holodomor seen as genocide of the Ukrainians, and d) reverence for OUN-UPA nationalist guerrillas and ‘heroes of the nation’ like Bandera, Shukhevych, and others. That is the community the third President of Ukraine, Viktor Yushchenko, used to call ‘my nation’. Those who do not share that assortment of predicates are not considered by the proponents of this identity to be ‘real Ukrainians’ and, according to them, should be re-educated. This type of identity, until recently, was shared by an apparent minority of Ukrainian population, which, although constituting a majority in the West of the country and prevalent among some elite groups – people of letters, diplomats, etc. – still constituted less than 15% of the total population. The reservation ‘until recently’ is important here, as I would argue that the events of 2014, the loss of Crimea, and the war in the South-East, have essentially changed the balance between the two types of identity in favour of the ‘political’ one, with a considerable part of Russians and Russian-speaking Ukrainians now holding with it. However, it is difficult to say how large that group exactly is until corresponding research has been carried out.

Numerous surveys demonstrate that there are two issues causing the drastic polarisation of Ukrainian society: the status of the Russian language and the preferred integration vector (to the West or to the East). It is no accident that the pretext for the beginning of mass protests in the Autumn of 2013 was the decision by Yanukovych to delay the signing of the Association and Free Trade Agreement with the EU. The first issue on the agenda of the Ukrainian parliament on the day of Yanukovych’s ousting on 22 February 2014 was the repeal of the liberal Kolesnichenko-Kivalov language law, which triggered the protests in the South-East that were later called ‘the Russian Spring’. In addition, in the past year another topic has joined the two, which has contributed to the split in the Ukrainian society, namely the preferred form of power structure in Ukraine: unitary state or federation.

When it comes to the status of the Russian language, this topic had mostly served as an electoral ‘friend-or-foe’ marker used by presidential candidates and parties who relied on the support of the South-East (demanding the elevation of that status). However, after coming to power, those presidents (Kuchma, Yanukovych) and parties (Party of Regions) used to give up their promises wishing not to antagonise ‘over trifles’ the part of population and the elite, which may be lesser in numbers but is more active politically. Especially since before Yushchenko came to power (in 2005), the gradual ousting of Russian language went at a slow pace, although from 1991 to 2005, the number of pupils in schools with Russian as instruction language decreased by more than half, from 54% to 24%.

Since 2005, the frontal attack on the Russian language has commenced in all areas of social life, first of all in education and the media. The process continued but was slowed down after Yanukovych came to power in 2010. In 2012, as a preparation for another electoral cycle, the team of Yanukovych had backed the Kivalov-Kolesnichenko Language Law (K-K) that elevated the status of the Russian language in those regions where it has been used by the majority of population, however, without imposing it where the apparent region majority would oppose that elevation. That law was in full accordance with the norms of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages and, as surveys demonstrated, such a compromise was supported by the explicit majority of the society and had entirely met the recommendations by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe from 7 July 2010 on providing languages with more rights, particularly in higher education, electronic media, and local government bodies (Council of Europe, 2010). Nevertheless, both public support (albeit unspoken) and recommendations by European experts did not hinder the opposition from launching a campaign against the K-K law. All opposition parties in the Verkhovna Rada soon had a common language bill advanced that, in fact, presupposed total Ukrainisation.

The K-K law had been repealed by Verkhovna Rada, but the repeal was never signed and the law is formally still in place. However, amendments to the law are being prepared to entirely emasculate the rights of the Russian language. There is little doubt that the current Verkhovna Rada elected in October 2014 will vote in favour of those amendments; there is limited representation of regions with high percentage of Russian-speaking population in that parliament, with 55 deputies from the South-East – Donetsk, Lugansk, Odessa, and Kharkov regions, 24 of whom represent ‘Petro Poroshenko Block’ and ‘The Popular Front’ party of Arseny Yatsenyuk – both openly anti-Russian. In contrast, Kiev and Western regions – Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil, and Chernivtsi – have 257 deputies. The large number of anti-Russian deputies from the South-East regions is due to two factors: the fact that they were included into nation-wide lists of pro-Maidan parties and the low attendance of voters in the South-East in general – and the voters of opposition parties in particular.

The events of the Autumn of 2013 and the Spring of 2014, referred to as a ‘coup d’etat’ by one part of the society (about one third) and a ‘conscious struggle of citizens who get united to protect their rights’ by another (a bit more than a third) (Mirror Weekly, 19 November 2014), were followed by the loss of Crimea and the war in the South-East. They also led to the marked aggravation of inter-civilian confrontation that, although not solely inter-ethnical (Ukrainians vs. Russians), does include such element.

Meanwhile, the information warfare against the militia of the South-East (‘the Russian Spring’) and Russia using all the resources of public and private (owned by oligarchs) mass media was in full swing, and, after the creation of a special Information Ministry by the new Ukrainian government, it will only increase. Total mopping-up of the information field from those who disagree with the mainstream narrative (‘Russia is aggressor, there are terrorists and regular Russian army fighting against Ukraine in the South-East…’) was effectively achieved by the end of 2014. The residents of the South-East and everyone in general who does not support the mainstream narrative are being labeled as ‘Moskals’, ‘Little Russians’, ‘fifth column’, and often are just dehumanised and designated by such terms as, for instance, ‘Colorados’.

Patriotic hysteria leads to mass cases of conflicts on interpersonal level, with decades-old friendships wrecked and families disintegrated, and in those regions of the South-East where the protest against the government is strangled by repressions (Dnipropetrovsk, Odessa, Kharkiv), cases of ‘guerrilla warfare’ are being registered, luckily with no casualties.

In order to evaluate the degree of hatred cultivated by ‘fighters of the information warfare’, I would refer to a case of a recent charity fair organised by teachers and eight-formers in a high school in Nikolayev as fund-raising for the participants of the so-called ‘anti-terrorist’ operation on the East of the country. Among the products prepared by schoolchildren and advertised for sale there were, for example, ‘tanks on Moscow’ cookies and stewed fruit drink called ‘the blood of Russian babies’ (Korrespondent.net, 2014).

The government legitimises radical Russophobe organisations by co-opting its activists into power structures, including those of law-enforcement. Thus, the position of the chief of Kiev regional police was filled by a deputy commander of the ‘Azov’ battalion, known for their usage of Nazi symbols. The commander of that battalion, Andrey Biletskiy, with the support of the ruling ‘Popular Front’ party, has been elected to the Verkhovna Rada from one of Kiev’s majority districts. Apart from him, a number of other nationalist-radicals known for their Russophobia have been elected to the parliament from majority parties’ lists, including ‘the Radical Party’ of Oleh Lyashko. There were no cases registered of the country leaders – the President or the Prime Minister – distancing themselves from the actions and radical anti-Russian rhetoric of their coalition partners. Moreover, Prime Minister Yatsenyuk himself actively participates in the fomentation of that anti-Russian hysteria. All of this promotes the intensification of the degree of hatred towards Russia and, one way or another, towards Russians. Among other things, the fomentation of ethnic strife is furthered by torch-light processions of nationalists held on a regular basis (with the government’s acquiescence) under the slogans ‘Glory to the nation, death to enemies’, ‘Ukraine above all’, and ‘Moskals to the knife!’ in many cities of the country, including Kiev and even Odessa.

The 2 May tragedy in Odessa was doubly horrifying: first of all, because of mass killings of the people, and second, because of the response of a considerable part of Ukrainian society to those events. The tragedy did not rally the society; on the contrary, it split it into those terrified by the events and those who directly or indirectly justified it by referring, inter alia, to the fact that there were ‘Colorados’ who were killed – not Ukrainians but enemies.

However, it cannot be claimed that it is Russians living in Ukraine who serve as enemies in the Ukrainian public discourse prevalent today. The enemy is mainly defined not in ethnic terms but ideologically – it is in the first place an opponent of the ideology universally propagated by the current government. Nevertheless, the civil confrontation in Ukraine is not entirely deprived of ethnic biases. The lack of commiseration, empathy, or compassion in relation to the death of ‘Colorados’ in Odessa, ‘jokes’ on the blood of Russian babies on a school charity fair, the openly Russophobe art exhibition titled ‘Kill a Colorado’ that took place in Kiev in December – those are not accidental events. They have been prepared by Ukrainian intelligentsia, just as the bloody civil war that led to the dissolution of Yugoslavia had been prepared by Serbian and Croatian scholars in arts and humanities.

One of the testimonial examples is a book published in Kiev in 2006, authored by a member of a Ukrainian Union of Writers and the former parliamentary deputy, Ivan Diak. The book is featured as a scientific edition: the academician of Ukraine National Academy of Sciences, Nikolai Zhulinskiy, was its supervisor and one of the reviewers was the head of the Ministry of Education and Science in the current Ukrainian government, Sergey Kvit (in the past, the activist of a right-wing radical organisation ‘“Trizub” named after S. Bandera’) (see: Diak, 2006). The book is a digest of xenophobic and chauvinistic views. It indicates, for example, that ethnic minorities (and particularly Russians in Ukraine) provided with the living space by the titular nation, are a potential ‘fifth column’ that could be used by Russia in its fight with Ukraine. There are several measures proposed to counteract that, specifically, an absolute isolation of minorities from their historical homeland, stimulation of political conflicts within minorities (the book directly refers to Ukrainian Russians), countrywide upbringing of children in the spirit of ethno-nationalist ideology, as well as compulsory Ukrainisation and introduction of ideological censorship of mass media.

If the tendencies we observe today persist, there is a high probability that the political conflict will develop into an ethnic one. With that in mind, room for the search for a break in the deadlock of a civil war is greatly narrowed, one of the reasons being the lack of any public discussion. Attempts to discuss some topics that would seem quite innocent for European discourse, for instance ‘federalisation’, are now elevated to the rank of crime on the whole.

Already, Ukraine President Viktor Yushchenko had set out against federalisation. In 2005, the head of Luhansk Oblast Administration Viktor Tikhonov and the former head of Kharkiv Oblast State Administration Yevhen Kushnaryov, who had publicly come out in favour of the federalisation of Ukraine, had criminal proceedings instituted against them for alleged separatism. And Yushchenko himself had openly admitted in 2006: ‘I will never accept the topic of federalisation and separatism. It’s a stab in our roots’ (Fakty.ua, 2006). Today, the topic of federalism is treated with disregard just in the same way. While addressing the Parliament on 27 November 2014, Petro Poroshenko categorically declared: ‘No federalisation!’ (Lb.ua, 2014). The topic is identified with separatism and disintegration of the country, and thus it remains informally banned.

References:

Council of Europe (2010). Available at: http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/education/minlang/Report/Recommendations/UkraineCMRec1_en.pdf (Accessed: 16 Dec 2014).

Diak, I. (2006) Piata kolona v Ukraine: zagroza derjavnosti. Kiyv

EMaidan (2014) ‘In Kiev, an exhibition under the slogan “Do not Pass By: Kill” Colorado!’ Available at: http://emaidan.com.ua/15448-v-kieve-otkrylas-vystavka-pod-lozungom-ne-proxodi-mimo-ubej-kolorada/ (Accessed: 28 January 2015).

Fakty.ua (2006) ‘Prezident Ukrainy Viktor Yucshenko “Federalizm I separatism eto nosh v nashi korni”’. Available at: http://fakty.ua/46445-prezident-ukrainy-viktor-yucshenko-quot-federalizm-i-separatizm—eto-nozh-v-nashi-korni-quot (Accessed: 29 January 2015).

von Hagen, M. (1995) ‘Does Ukraine Have a History?’ Slavic Review, 54(3), pp. 658-673.

Himka, J. (1999) Religion and Nationality in Western Ukraine: The Greek Catholic Church and the Ruthenian National Movement in Galicia. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

LB.ua (2014) ‘Poroshenko Iklyuchaet Federalizatsiyu’. Available at: http://lb.ua/news/2014/11/27/287446_poroshenko_isklyuchaet_federalizatsiyu.html (Accessed: 29 January 2015).

Korrespondent.net (2014) ‘At the charity fair in Nikolayev treated “The Blood of Russian babies”’. Available at: http://korrespondent.net/ukraine/comunity/3453219-na-shkolnoi-yarmarke-v-nykolaeve-uhoschaly-krovui-rossyiskykh-mladentsev (Accessed: 28 January 2015).

Khmelko, V. (2004) ‘Linguistic and ethnic structure of Ukraine: regional differences and trends of change since independence. Scientific Notes of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy,’ Social science, 32.

Miller, A. (2003) The Ukrainian Question: Russian Nationalism in the 19th Century. Central European University Press.

Minakov, M. (2014) ‘Moses und Prometheus. Die Ukraine zwischen Befreiung und Freiheit,’ Transit: Europäische Revue, 45, pp. 55-70.

Mirror Weekly (2014). Available at: http://zn.ua/UKRAINE/okolo-30-ukraincev-schitayut-maydan-gosperevorotom-159252_.html (Accessed: 16 Dec 2014)

Pogrebinskiy, M. (ed.) (2013) The Crises of Multiculturalism and Problems of National Politics. Moskva Ves`mir.

Pogrebinskiy, M. (ed.) (2010) Russian Language in Ukraine. Khar’kov: HPMMS.

Pogrebinskiy, M. (ed.) (2005) The “Orange Revolution”: Ukrainian version. Moskva: Evropa.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – War in Ukraine: Why We Should Say No to International Civil Society

- ‘Eastern Ukraine’ is No More: War and Identity in Post-Euromaidan Dnipropetrovsk

- Opinion – Rethinking History in Light of Ukraine’s Resistance

- Opinion – Putin’s Obsession with Ukraine as a ‘Russian Land’

- Opinion – The Myth of Being Anti-Racist and Anti-War in the Ukraine Conflict

- Opinion – Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s Leadership and Europeanness in Ukraine