To find out more about E-IR essay awards, click here.

—

This essay proposes that security is a practiced, strategically and pragmatically, to protect abstract or concrete value. This practice involves i) the means by which an existentially threatening aura is added to an issue, with reference to a particular object(s), and ii) the mobilization of apparatus to manage that issue. After outlining and problematizing some key features of Copenhagen School (CS) securitization theory, this paper, drawing on Balzacq (2009; 2011; 2015), will progress an understanding of the strategic-pragmatic nature of securitizing practices. Thereafter, in line with ideas from Floyd (2010; 2011), the paper will contend that any conceptualization of security requires the inclusion of security practices taken to address “threatening” issues. Thus arguing that security should be conceptualized as a strategic practice comprising the practices used to securitize an issue, i.e. securitizing practices, and the practices used to address it, i.e. security practices.

The Copenhagen School

Until the 1980s there was little self-conscious reflection on the assumptions that underpinned Security Studies. It was supposed that security related to military or diplomatic interactions between states, through which they ensured their own survival (Bilgin et al, 1998: 133-136). State interactions were set against, and justified with reference to, the ever-present dangers of a necessarily anarchic international system (Waltz, 1979: 88-90). However, significant Constructivist and post-structural reflective inquiry led to the emergence of several ‘broadening’ schools, endorsing examination of security beyond a state-centric military discourse, and highlighting the hazards of such a discourse (Buzan and Hansen, 2009: 200). What constituted ‘security’ became highly contested, creating an impasse (Waever, 2011: 469): If traditionalist approaches were rejected there was a danger that ‘everything will become security’; the analytical coherence and utility of the discipline would be lost (Khong, 2001: 232-36; Hampson, 2008: 9, 231). However, if no widening occurred theorists would be ill-equipped to examine ‘emerging’ security issues, such as mass migration, infectious disease, ethnic conflict, and transnational crime (Bilgin et al, 1998: 141). Furthermore, ethical concerns and the potential normative utility of security, and scholarship thereof, would be ignored (Bilgin et al, 1998: 141-142, 156-157).

The Copenhagen School (CS) offered a ‘solution’ to this impasse by situating their approach between traditionalists and radical broadening schools (McDonald, 2008a: 68; Waever, 1995: 49; Waever, 2011: 469). They maintained, in line with traditionalists, security is about survival and existential threats (Buzan et al, 1998: 21). However, existential security threats are not found in things, but are social constructs (ibid: 21-26): As Waever (2011: 467) puts it ‘securityness’ is ‘a quality, not of threats but of their handling, [securitization] theory places power not with ‘things’ external to a community but internal to it’; thus, security is a constitutive quality added to issues through a process of inter-subjective construction; i.e. securitization. Securitizing actors, generally political elites, securitizes an issue by persuading an audience(s) it is a matter of ‘security’ through illocutionary speech acts, presenting a logic that, if exceptional means aren’t used to manage the issue, some referent object will be destroyed (Buzan et al, 1998: 26). Thus, the existentially threatening aura added to an issue in the collective outlook of a group is indicative of its extreme prioritization; the existential nature of the perceived threat mandates exceptional action to manage the issue and secure the referent object (ibid: 26-27).

CS securitization theory is progressive, as it does not theoretically presuppose states are the only objects of security or securitizing actors,[1] allowing for limited broadening and endorsing the examination of environmental, economic, societal and political security issues (Buzan et al, 1998, see ch. 4, 5, 6 & 7). It also encourages a more reflexive analytical approach that provokes critical engagement with theoretical specifics (Wilkinson, 2007: 8).

Furthermore, CS demonstrates that security is a means by which societies prioritize issues in order to lift them above ‘normal’ politics (Buzan et al, 1998: 23-24). Thus, elucidating that any potential consequential utility of security lies in a society’s ability to use it to mobilize people and resources. This raises two questions: Who should use security? How should they use it?[2] CS offers relatively definitive a priori answers; preconditioning the theory so ‘desecuritization is preferable in the abstract’, and denying the possibility of security having widespread ethical utility (Buzan et al, 1998: 29; Waever, 2011: 469-470).[3] Thus, for CS, the normative utility of their approach lies in exposing the negative consequences of securitization in order to encourage desecuritization (Waever, 2011: 469). However, the explanatory power of the theory and analytical utility of the theoretical apparatus proposed, on which their normative assertions are contingent, have been doubted (Balzacq, 2011: ch.1 Browning and McDonald, 2011: 241-242; Wilkinson, 2007: 8-9). Assessing whether the Copenhagen School captures how security really functions may bring the credibility of their abstract dismissal of security’s value into question.

Securitization is a Speech Act?

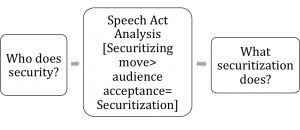

Balzacq (2011: 3) problematizes the CS theoretical framework based on their assertion that securitization is a conventional linguistic procedure, namely a speech act. CS supposes a complete illocutionary speech act, i.e the communicatory effectiveness of a conventional procedure and its immediate consequences, will achieve a securitizing actors desired ends (Waever, 1995: 55); the successful communication of meaning to an audience and acceptance of that meaning is indicative of securitization (Balzacq, 2011: 1). Thus, the CS approach is predisposed to analysis that follows a linear progression:[4]

The research focus is firmly on the speech act or ‘moment of securitization’ (Waever, 2011: 477). Here, the securitizing move is disassociated from the audience, who are assumed to be receptive and simply give or refuse acceptance (Buzan et al, 1998: 30-31). Resultantly, for CS, securitization is a ‘self-referential’ practice because it is in the process of referring to an issue as one of security, i.e. uttering certain utterances, that an issue is constituted as an existential threat (Buzan et al: 1998: 24; Waever 1995: 55). Balzacq (2011: 5) argues this claim stems from confusion between illocutionary speech acts and the ‘total situation of a speech act’ (including perlocutionary acts), or at least between illocutionary success and perlocutionary effects. Whereas illocutionary acts are conventional, and their communicatory success contingent on meeting four ‘felicity conditions’,[5] perlocutionary acts relate to the ‘desired causal result of many speech acts’ (ibid: 4-5). Perlocution is not conventional, but will be circumstance-specific and includes ‘all those effects, intended or unintended, often indeterminate, that some particular utterance in some particular situation may cause’ (Austin, 1962: 52, 101-32 cited in Balzacq, 2011: 5); it is more complex in nature and consequence than illocution, and is not fully encompassed in the CS model of securitization as “speech acts” (Balzacq, 2011: 6).

Resultantly, CS misrepresents the role of contextual factors and the audience in constituting security issues and the form of the securitization process itself. Focusing on speech acts is theoretically restrictive and leaves theorists predisposed to examination of illocution, rather than a complex inter-subjective process of securitization and the centrality of perlocutionary acts (Balzacq, 2009: 11; McDonald, 2008b: 564, 568). This has led to applications of securitization theory that disregard broader political, cultural and historical landscapes, and overlook the significance of power positions, structural constraints and facilitators, and audience agency (Balzacq: 2011: see ch.1); thus, leaving original formulations of securitization theory ill equipped in unfamiliar contexts, lacking theoretical dexterity, and tending toward state-centrism and elite-centrism (Booth, 2007: 166; McGahan, 2009: 3; Wilkinson, 2007: 10).

Securitizing Practices

Balzacq (2009: 12-18; 2011: 3-15) offers a conceptualization of security that confronts the problems highlighted above. To summarize, security is a dynamic strategic-pragmatic process, constituted by securitizing actors, and actions taken by those actors, understood within a particular context and shaped by audiences and relative power positions (Balzacq, 2011: 3). Balzacq (ibid) also re-conceptualizes securitization as a set of practices through which a variety of linguistic and political tools[6] are mobilized in order to add an unprecedented threatening aura to an issue, such that ‘a customized policy must be undertaken immediately to block its development’ (Balzacq, 2009: 20; Balzacq, 2011: 4). These conceptualizations guide analysts towards more holistic examinations of security and its functions; placing particular emphasis on the inter-subjective nature of the process and encouraging greater examination of how audiences constitute the form and consequences of security. Using these conceptualizations, it is possible to identify securitizing practices that encourage ‘the acceptance of empowering audiences of a securitizing move’ (Balzacq, 2011, 9). [7] These securitizing practices involve the mobilization of tools within a certain historical, cultural, political, and linguistic context to incept and foster inter-subjective understandings of certain issues as existentially threatening (Balzacq, 2011, 14). Securitizing practices derive meaning from their context; the practices and tools available to actors are shaped, and their effectiveness facilitated and constrained, by context and the predispositions of the audiences they are appealing to (ibid: 9-11). As such, the manner in which security issues are constructed will depend upon the nature of; the securitizing practices and tools used, the context, and the thoughts, feelings, desires, motivations and actions of all actors involved. Balzacq details a framework for analysis, covering three distinct levels (agents, acts and context) and identifying several interrelated units within each level.[8] From this framework, tailored context-specific methodologies can be devised for identifying and understanding securitizing practices, offering arguably greater explanatory power in a wider variety of contexts than CS, thus enhancing the analytical utility of securitization as a theoretical approach for understanding securitizing practices.

Securitizing Practices + Security Practices

However, neither of CS’ or Balzacq’s conceptualizations explicitly encompasses the entire practice of security. For Floyd (2011: 428-9), referring to the third and fourth felicity conditions of illocution, the problem is one of sincerity; securitizing actor must be sincere when making securitizing moves, i.e. securitizing actors must genuinely intend to use some extraordinary practice to manage “threatening” issues. Security practices must be sincerely proposed and executed to evidence the prioritization of an issue;[9] i.e. for a securitization to be complete there must be some sort of security practice following the securitizing move. Thus, Securitization = Securitizing Move + Security Practice (Floyd, 2010: 54).

Incorporation of this development into the schema proposed by Balzacq poses new challenges as a wider range of agents, acts, and contextual factors are constitutive of the securitizing move, and perlocutionary effects are central to the securitization. However, drawing on the essence of Floyd’s proposal, the constitution of an issue as one of ‘security’ includes the totality of practices used to securitize it, i.e. securitizing practices, and practices used to address it, i.e. security practices. Thus, security should be conceptualized as a strategic practice comprising securitizing practices and security practices. Security then, refers to the practices through which an issue gains and retains an existentially threatening aura in the collective outlook of a group and the tangible consequences of thereof.

This conceptualization can account for the fact that the nature of the security practices which a securitizing actor wishes to use shapes the securitizing practices mobilized and which audiences are appealed to. Furthermore, the CS linear framework for analysis described earlier is not presupposed under this conceptualization. Although securitizing practices are used to prioritize issues and involve them in security agendas in order to mandate security practices, this is not their only function (Vuori, 2008: 68: 78). In contexts where power is highly centralized and almost all government policy is related back to national security, e.g. DPRK, security practices are not exceptional, but the norm; in such contexts, it will be possible to use security practices before mobilizing securitizing practices to legitimize them.[10]

Securitizing practices are also regularly used for ‘reproducing the security status of an issue’ (Vuori, 2008: 76). Indeed, once security practices, e.g. military deployments or extraordinary immigration policies, have been enacted securitizing practices, e.g. strong security rhetoric and portrayals of an ‘enemy’ and ‘threat’, tend to intensify rather than diminish (Burke, 2007: 125). Members of the so-called Paris School also claim securitizing practices and security practices are routinely used by states, as a political technology, to control populations (Bigo, 2002: 65; Burke, 2007: 124; Vuori, 2008: 76). Whether or not these more radical perspectives outlined accurately depict security, they do highlight that the relationship between securitizing practices and security practice is more complex than CS, or to some extent Balzacq, account for.

The strategic practice of security often involves a set of cumulative and incremental processes whereby policy responses, media portrayals and mobilization of security policy serve to reinforce the construction of existential threats, while simultaneously facilitating further mobilization of security practices; consequently, it may be impossible to identify a moment of securitization. This conceptualization acknowledges that securitizing practices and security practices may well overlap and mutually reinforce each other. As McGahan (2008: 33) states ‘discourses of threat do not directly cause policy responses. Rather, they frame policy debates, widening or narrowing choices for legitimate and appropriate action.’ Indeed, securitization is not just a means of prioritization, but also a means of justifying, legitimizing, institutionalizing, and legalizing security practices (Balzacq, 2015: 4-7). Conceptualizing security as the sum total of securitizing practices and security practices allows for examination of how the two interact, rather than assuming simple causality.

Some Advantages

The conceptualization proposed is advantageous for several reasons. In line with CS assertions, at present, operationalizing this conceptualization would demonstrate security is generally the preserve of states or supra-national organizations, as they have the requisite power, and control of the political machinery. As Taureck (2006: 55) puts it the practice of security ‘is far from being open to all units and their respective subjective threats, but rather it is largely based on power and capability and therewith the means to socially and politically construct a threat.’ However, theoretically security could be used by anyone (e.g. civil society, supra-national organizations, academics and individuals) to protect anything and it is not presupposed that states are legitimate referent objects of security. Thus, allowing for deeper critical examination of how states (mis)use security and investigation of how it could be better used, including by other agents.

Critics may argue that, in abandoning the three-stage linear model outlined by CS, some of the value of the theory, found in its tight framework for analysis, will be lost. This will impact upon ease of application and specifics of applications will be more contested/contestable. However, this may be advantageous:

It manifests a requirement for rigorous investigation of contexts, power-relationships and cultural norms in understanding the relationships between securitizing actors, acts, audiences, and the practice of security. Furthermore, dispensing with a degree of formality will allow for more interpretive critical engagement and authorship of appropriate theoretical apparatus in unfamiliar contexts, and relating to unfamiliar issues. Rather than detracting from analytical utility, such a conceptualization may result in greater conceptual dexterity, theoretical reflexivity, and methodological pluralism, thus, increasing analytical utility.[11]

Additionally, in explicitly acknowledging a degree of interdependence between securitizing practices and security practices, a more holistic examination of practices of security may facilitate a deeper understanding of the pervasiveness and functionality of security in society. Indeed, as the importance of power relationships is emphasized, this conceptualization will have appeal to scholars who view security as a ‘political technology’ utilized in the perpetuation of the states position as a security provider (Bigo, 2002: 65; Burke, 2007: 124).[12]

Despite this, the conceptualization is not completely incompatible with positivist schools. Although the defining CS text (Buzan, 1998: 40) cautioned against any notion of objective security issues, Floyd (2011: 430) and Waever (2011: 472) reintroduce ‘objective’ existential threats[13] as a consideration; demonstrating that whether something actually threatens the existence of an object or value may be divorced from whether it is perceived or socially constructed as an existential threat. Indeed, acknowledging the existence of securitizing practices does not entail a denial of ‘objective existential threats’, merely that securitizing practices may be used as a means of handling an issue, whether or not a referent thing is (or can be) objectively threatening.[14]

Lastly, security is conceptualized as something that is utilized, for good or ill, from inception to conclusion, to ensure the protection of a certain value. It does not abstractly presuppose that the strategic practice of security is good or bad: While potentially augmenting the analytical utility of securitization theory, this conceptualization opens the door for the establishment of criteria to normatively assess the moral legitimacy of referent objects, and the consequential utility of strategically practicing security as a means of addressing issues.[15] Thus, it becomes vital to re-examine when and how security should be practiced. Developing a framework for judging when security could legitimately[16] be practiced requires further investigation. However, a tentative suggestion for what could constitute a legitimate referent object can be drawn from Human Security, which already informs the National Security policies of Canada and Norway (Axworthy, 2001: 19-23; Floyd, 2007a: 49-59; Floyd, 2011: 431; Suhkre, 1999: 265-269).[17]

Conclusion

Conceptualizing security as a strategic practice can elucidate how ‘the production and employment of security knowledge’, securitizing practices and security practices have ‘rendered peoples and social groups less secure’ (Bilgin, 2010, 620), while allowing for the possibility of utilizing security to protect morally legitimate concrete or abstract value. By placing the processes and practices involved in securitization and security management at its heart, the conceptualization outlined in this paper moves emphasis from purely discursive examinations of securitization, and endorses a more sociological understanding of how the strategic practice of security functions in reality. Emphasis on the centrality of audiences and the need to thoroughly contextualize any examination of a security issue make claims of Western-centrism and elite-centrism less justifiable. Moreover, in explicitly endorsing methodological pluralism, the conceptualization facilitates the organic development of a coherent, yet reflexive, theoretical approach for understanding the multi-facets of how security issues ‘emerge and dissolve’ and is compatible with positivist and post-positivist schools of IR. Thanks to Balzacq’s (2011: 36-37) framework for analysis the analytical utility of CS securitization theory is retained, if not enhanced. Whilst the inclusion of developments by Floyd (2007b, 2011) makes incorporation of normative approaches more tenable, opening the door to comprehensive normative assessment of the consequential utility of securitizing practices and the security practices. Thus, security should be conceptualized as a strategic practice comprising securitizing practices and security practices.

Bibliography

Axworthy, L. (2001) Human Security and Global Governance: Putting People First Global Governance, Vol. 7, 1: 19-23

Balzacq, T. (2009) “Constructivism and securitization studies” in The Routledge Handbook of Security Studies (Routledge) [Available at: http://graduateinstitute.ch/files/live/sites/iheid/files/sites/developpement/shared/developpement/cours/E777/Securitization_Balzacq.pdf Accessed on: 7/12/2014; page numbers as printed]

Balzacq, T. (2011) Securitization Theory: How security problems emerge and dissolve (Routledge)

Balzacq, T. (2015) Legitmacy and the “logic of security” forthcoming in Balzacq, T. Contesting Security: Strategies and Logics (Routledge) [Available at: http://samples.sainsburysebooks.co.uk/9781136162732_sample_787415.pdf]

Bigo D. (2002) “Security and Immigration: Toward a Critique of the Governmentality of Unease” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 2002 27: 63-92

Bilgin, P. Booth, K. and Wyn Jones, R. (1998) “Security studies: the next stage?” Naçao e Defesa, 84(2): 129–157

Bilgin, P. (2008) “Critical Theory” in: Williams P Security Studies (Routledge)

Booth, K. (2005) “Beyond Critical Security Studies” In: Booth, K. (Ed.) Critical Security Studies and World Politics (Lynne Rienner)

Booth, K. (2007) Theory of World Security (Cambridge University Press)

Browning, C. and McDonald, M. (2011) “The future of critical security studies: Ethics and the politics of security” European Journal of International Relations 19(2) 235–255

Burke, A. (2007) “Australia Paranoid” in Burke, A. and McDonald M. Critical Security in the Asia-Pacific (Manchester University Press)

Buzan, B. And Hansen, L. (2009) The Evolution Of International Security Studies (Cambridge University Press)

Buzan, B. Waever, O. and Wilde, J. (1998) Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Lynne Rienner Publishers)

Hampson, F. O. (2008) “Human Security” in in Williams, P. D. (Ed.) Security Studies: An Introduction (Routledge)

Floyd, R. (2007a) “Human Security and the Copenhagen School’s Securitization Approach: Conceptualizing Human Security as a Securitizing Move” Human Security Journal Volume 5: 38-59

Floyd, R. (2007b) “Towards a Consequentialist Evaluation of Security: Bringing Together the Copenhagen and the Welsh Schools of Security Studies ” Review of International Studies Vol. 33 (2) 327-350

Floyd R (2010) Security and the Environment: Securitization Theory and US Environmental Security Policy (Cambridge University Press)

Floyd, R. (2011) “Can securitization theory be used in normative analysis? Towards a just securitization theory” Security Dialogue 42: 427-439

Khong, Y. F. (2001), “Human Security: A Shotgun Approach to Alleviating Human Misery?” Global Governance 7(3): 231–236

McGahan, K. (2008) Managing Migration: The Politics of Immigration Enforcement and Border Controls in Malaysia Unpublished: Article forthcoming. [Available at: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=4osGz3rIpwcC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false]

McGahan, K (2009) “The Securitization of Migration in Malaysia: Drawing Lessons beyond the Copenhagen School” delivered at Paper presented at the annual conference of the International Studies Association, February 16-19, 2009

McDonald, M. (2008b) “Constructivism” in Williams, P. D. (Ed.) Security Studies: An Introduction (Routledge)

McDonald, M. (2008b) “Securitization and the Construction of Security” European Journal of International Relations Vol. 14 (4) 563-587

Reckwitz, A. (2002) “Toward a Theory of Social Practices: A Development in Culturalist Theorizing” European Journal of Social Theory Vol.5 243-263

Sarvimäki, A. (2006) “Well-being as being well a Heideggerian look at well-being” International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being Vol. 1, 1: 4-10 [Avaliable at: www.ijqhw.net/index.php/qhw/article/download/4903/5171]

Suhrke, A. (1999) Human Security and the Interests of States Security Dialogue 1999 30: 265-276

Taureck, R. (2006) “Securitization theory and securitization studies” Journal of International Relations and Development Vol 9 (1) 53-61

UNDP (1994) Human Development Report 1994 (Oxford University Press) [Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/255/hdr_1994_en_complete_nostats.pdf Last accessed on: 8/12/2014]

Vuori, J. A. (2008) Illocutionary Logic and Strands of Securitization: Applying the Theory of Securitization to the Study of Non-Democratic Political Orders European Journal of International Relations 14: 65-99

Wæver, O. (1995) “Securitization and Desecuritization” in Ronnie, D.L. (ed.) On Security, New York: Columbia University Press.

Waever, O. (2011) Politics, Security, Theory Security Dialogue 42: 465-480

Wilkinson, C. (2007) “The Copenhagen School on Tour in Kyrgyzstan: Is Securitization Theory Useable Outside Europe?” Security Dialogue 2007 38: 5-25

Wyn Jones R (2005) “On emancipation: Necessity, capacity, and concrete utopias” in: Booth. K, (ed.) Critical Security Studies and World Politics (Lynn Rienner)

Waltz, K. (1979) Theory of International Politics (Addison Wesley Publishing Company)

[1] This is not universally accepted; Booth (2007: 166-167) argues that any discourse-centric theory will necessarily be state-centric and elite-centric, as states and elites dominate discourse.

[2] The claim that conceptualizations of security should be developed with normative utility in mind remains puzzlingly controversial. Particularly when working with securitization theory, consideration of the conceptualization’s normative utility is vital. As Waver states ‘the securitization approach points to the inherently political nature of any designation of security issues and thus it puts an ethical question at the feet of analysts, decision-makers and activists alike: why do you call this a security issue? What are the implications of doing this – or of not doing it?’ (Wæver, 1999: 334).

[3] CS does add a caveat; stating ‘a vote for desecuritization comes directly from the theory… [but] the analytical set-up allows empirical analysis of the possible advantages of handling a particular challenge within the format of both security and non-security’ (Waever, 2011: 469).

[4] This characterization incorporates recent clarifications of securitization theory by Waever (2011, 476) in light of developments. By re-emphasizing the need to ask ‘who does security?’ before securitization and ‘what securitization does?’ afterwards Waever (2011) promotes ‘a more cumulative research programme’ that increases focus on other factors that may affect the process. For a more detailed account and theoretical justification of this model see Politics, Security, Theory (Waever, 2011: 476-477).

[5] These include; a preparatory condition (the existence of a conventional procedure), an executive condition (determining whether the procedure has been executed), a sincerity condition (whether participants sincerely have certain thoughts or feelings), and a fulfillment condition relating to whether actions accord with the procedure (Balzacq, 2011: 5).

[6] Tools are defined as ‘routinized sets of rules and procedures that structure interaction between individuals and organization’ (Balzacq, 2011, 17).

[7] This acceptance is presumed to be both moral and formal. Securitizing actors will generally strive for consent from both formal institutions and a wider public, as both will have a ‘direct causal connection’ with the actors desired goals (Balzacq, 2011, 9).

[8] See the ‘Levels and Units of Analysis in Securitization’ in Balzacq (2011: 36).

[9] To caveat, this is not to say that the securitizing actor will be sincere about the referent object they are trying to protect. Indeed, states often utilize ‘security’ in order to mobilize extra-political means to secure there own position as security providers or some other referent object, but do so in the name of something more palatable to their audiences.

[10] Balzacq (2010, 19) does allow space for this phenomenon, and includes policy tools as units of analysis in the acts level of analysis, defining one as ‘an instrument which, by its very nature or by its very functioning, transforms the entity (i.e., subject or object) it processes into a threat.’ However, he denies that ‘securitization predates security practices’ (Balzacq, 2015: 2).

[11] One methodological possibility emphasized by both Floyd (2007b: 42) and Balzacq (2011: 46-50) is process tracing. Incorporating process tracing as a methodological approach may encourage traditionalist engagement with securitization theory. This may is redoubled by Floyd’s (2011: 428, 431) assertion that considerations of “objective” existential threats should feature in accounts of securitization.

[12] The methodological pluralism of Foucauldian discourse analysis, in line with the Paris School (Bigo, 2002: 70), is another methodological possibility.

[13] This is a contentious point in securitization theory, with Waever (2011: 472) asserting, in line with positivism, that objective existential threats can be ‘measured scientifically outside politics’ whether or not they have a ‘security label attached’; while Balzacq (2015: 4), in line with post-positivism, contests objectivity can only refer to ‘the inter-subjective solidification of a social fact.’

[14] This paper was conceived with constructivism and post-positivism in mind; as such the justifications proposed may stand opposed to positivism; however, in essence, the conceptualization itself need not.

[15] A consequentialist framework could confront the problem of broadening. Security would have to be used selectively as the main danger of excessive broadening is that everything could become security, thus destroying its consequential utility; this would have to be incorporated into a framework of criteria for assessing moral rightness consequences of using security (see Floyd, 2007b).

[16] This refers to moral legitimacy, rather than simply popular support; conceptualizations will be highly contested. However, Floyd (2011) and Balzacq (2015: 1-11) and Waever (2011: 471-473) have already added enlightening contributions to this debate in relations to securitization.

[17] A connected possibility would require the development of a cross-disciplinary understanding of human well-being. Psychology (Sarvimäki, 2006: 5-9) can offer understandings of holistic well-being, incorporating material needs, in line with basic Human Rights (UNDP, 1994: 23), and non-material needs for emancipation, in line with the Welsh School’s ideas regarding emancipation (Bilgin, 2008 89-99; Booth, 2005: 259–278; Wyn Jones, 2005: 215–235).

—

Written by: George May

Written at: University of Birmingham

Written for: Professor Stefan Wolff

Date Written: December 2014

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Security as a Normative Issue: Ethical Responsibility and the Copenhagen School

- Multidisciplinary Approaches to Security: The Paris School and Ontological Security

- Climate Security in the United States and Australia: A Human Security Critique

- Outsourcing Security at Sea: Constructivism and Private Maritime Security Companies

- Is Security Possible? The Use of Face Coverings to Reduce Transmission of Covid-19

- The Protection Paradox: Why Security’s Focus on the State Is Not Enough