How Successful Have the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia been in dealing with the Khmer Rouge? A study of Bureau-shaping by Individual Bureaucrats.

Roger MacGinty writes: “…hybridity demands that we look backwards and ask questions about origins and antecedence” (MacGinty, 2011, p. 78), and it is with this in mind that it will be useful to trace the origins of the bureau-shaping process in Cambodia between June 21st 1997 to June 6th 2003. The fuse was lit on June 21st 1997 when co-Prime Ministers Norodom Ranariddh and Hun Sen sent a letter from Cambodia to the United Nations requesting assistance in the bringing to trial of members of the Khmer Rouge who had allegedly been involved in war crimes between 1975 and 1979. The six years of subsequent negotiations included various actors among whom were: The Cambodian People’s Party (CPP), The United Nations (UN) and separate states and associations.

My interest stems from a first visit to Cambodia in 2006 and an attempt to absorb the history of the past atrocities of the Khmer Rouge. This affected me deeply and increased my curiosity into how political conflict on this scale could develop into unprecedented atrocities. After tours of Cambodia in the summers of 2011 and 2013 and in the pursuit of my degree in International Relations, I became increasingly fascinated by forms of hybrid peace and the institutions which decide the peace-keeping format and the quality of peace achieved. In my final visit to Cambodia in September 2013, in the aftermath of the national elections, I had conversations with indigenous people who cited certain bureaucrats who had manipulated politics in their country. Of course these frustrations reflected the opinions of middle-aged, urban, working-class males, yet their opinion was not without value. One of the issues that was of obvious concern to them was the current administrative process of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). With these public perceptions of the contemporary ECCC the questions remain: has the ECCC been successful in dealing with the Khmer Rouge? How can success be defined? Whose success is it?

I also want to explore the phenomenon of bureau-shaping in the ECCC because of the factors that make it unique. It was the first international tribunal to earned the term ‘hybrid’ due to the multiplicity of organizations that were involved in the formation of the ECCC. In addition, unlike the tribunals of Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia which were born from an immediate international response, Cambodia only requested international support from war crimes which had occurred 18 years before. In those years, key events had driven Cambodia into a totalitarian state which been influenced by various individuals at home and prestigious actors abroad.

To explore and understand the bureaucratic influences in the formation of the ECCC, there is no lack of information. I have used recent literature (Fawthrop & Jarvis, 2004), (Kiernan, The Pol Pot regime: race, power, and genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79, 1996) and (Gottesman, 2003) along with letters, interviews and newspaper articles displaying a variety of views. There have been multiple articles which have explored the contemporary successes and failures of the ECCC through comparisons with other international tribunals such as the International Criminal Tribunal of Rwanda (ICTR) and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) (Stensrud, 2009) (Nouwen, 2006) (Mani, 2002). I have, however, chosen bureau-shaping, a subset of new institutionalism, as a useful method of understanding the origins of the ECCC. Bureaucracies in themselves are subject to rules which ensure that they are powerful enough to be efficient. However, in their very nature, they are not so powerful as to be autonomous and this, in turn, makes them accountable for their every decision (Cairney, 2012, p. 72). With multiple actors involved in the inception (and inevitably the outcome) of the ECCC, it fits neatly into this definition of a bureau. In the bureau itself, the key component is the individual who drives the shaping of the bureau in their own fashion, which is where Dunleavy’s bureau-shaping model becomes an important element in the understanding of the motivation of a bureaucrat. Dunleavy states that, unlike previous perceptions of the budget-maximising bureaucrat pursuing power, money and prestige, a bureaucrat’s goal is to mould policy within a bureau by promoting ‘positive values’ such as the provision of a collegial atmosphere and a central location, rather than ‘negative values’ of routine work and a peripheral location.

This dissertation will include a chapter on three groups relevant to this bureau-shaping process: Chapter 1, the Cambodian People’s Party will examine the roles of President Hun Sen and bureaucrat Sok An, Chapter 2, the United Nations will examine Thomas Hammarberg, The ‘Group of Experts’, Hans Corell and Kofi Annan, and, finally, Chapter 3, individual states will examine bureaucrats within the United States of America and China. Each chapter will begin with an introduction of the group and the circumstances leading to its involvement in the bureau-shaping process of the ECCC. The chapters will be divided into sections focusing on influences that will include: individual contextual backgrounds, initial aims in bureau-shaping the ECCC, analyses of events and the ultimate effects of the bureaucrats on the ECCC. The conclusion will contextualise the impact of the bureaucrats using Dunleavy’s bureau-shaping model, with a specific interest in determining whether a particular bureaucrat had pushed for ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ values.

LITERATURE REVIEW[1]

Roger MacGinty’s International Peacebuilding and Local Resistance explains the term hybridisation as the ability of multiple actors to function in the international arena. MacGinty writes that international peacebuilding is a hybrid clash between liberal peace and local actors. From this assumption, he provides four factors that are critical for hybrid peace: “the ability of liberal agents to enforce acceptance of liberal peace, the ability of liberal peace agents to incentivise local engagement with the local peace, the ability of local actors to present alternatives to the liberal peace and the ability of local actors to ignore, resist and subvert the liberal peace” (MacGinty, 2011, p. 9). Whether forms of liberal peace and local actors can coexist within the judicial mechanism is debatable. Sarah M.H. Nouwen’s ‘Hybrid courts’: The hybrid category of a new type of international crimes courts is a research paper in which, while considering and comparing the positive and negative aspects of multiple hybrid courts, she concludes that the hybrid court system is fundamentally flawed. She quotes Payam Akhavan’s description that they represent “judicial romanticism” (Nouwen, 2006, p. 213) (Akhavan, 2001, p. 31). On the other hand, Helen Horsington and Laura Dickerson, while accepting many of the flaws in the hybrid justice mechanism, see it as a possible future mechanism for international justice since the “hybrid KRT (Khmer Rouge Tribunal) reflects the social, cultural and historical context of the human rights atrocities… (and) has the potential to provide a meaningful process of accountability that is acutely important in a transitional post-conflict context.” (Horsington, 2004, p. 21) (Dickerson, 2003). While this hybridisation could provide an important international model for the way in which particular bureaux could be formed, where they are placed and how they were influenced by the ECCC, in these chapters the focus will be on the history of the formation of the ECCC in which an examination of Patrick Dunleavy’s Democracy, Bureaucracy and Public Choice is critical.

My main source of bureau-shaping literature comes from Patrick Dunleavy’s Democracy, Bureaucracy and Public Choice. The author seeks to explain the shaping of bureaux through his critique of two key figures in bureau-shaping: Anthony Downs and William A. Niskanen. While their initial theses attempt to provide an economic explanation, they both emphasise the role of the individual bureaucrat.

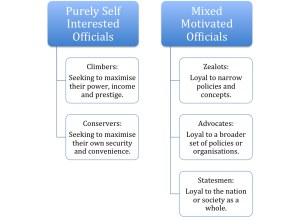

Anthony Downs’ Inside Bureaucracy presents a pluralist model in which the individual is the centre of the bureau. His fundamental idea is that bureaucrats are mostly motivated by self-interest. His conclusions are firstly: “Officials seek to attain their goals rationally: that is, in the most efficient manner possible… This means that all agents in the theory are utility maximizers. In practical terms, this implies that whenever the cost of attaining any given goal rises in terms of time, effort, or money, they seek to attain less of that goal, ceteris paribus.” (Downs, 1964, p. 4). Secondly, he categorises self-interested bureaucratic behaviour in this way, which I here reproduce in table-form (Downs, 1964, pp. 4-5):

Downs’ theory of bureaucracy promotes a pragmatic approach, while his attempt to categorise and simplify the behaviour of individuals presents a vital stepping-stone in the discussion of the bureau-shaping phenomenon of the ECCC.

Niskanen’s New Right Model is largely focused on economic functions and, unlike Downs’s theory, Niskanen underplays the self-seeking role of the individual while emphasising the role of the bureau: “the bureaucrat’s motives are: salary, perquisites of the office, public relations, power, patronage, output of the bureau… all are a positive function of the total budget of the bureau during the bureaucrat’s tenure” (Niskanen, Bureaucracy: Servant or master, 1973, pp. 22-3). Whilst the two models share some views about bureaucratic motivations, Nickanen argues that self-regarding motivations are critical in the promotion and increase of the importance of the bureau, and he writes that the objectives of bureaucrats are “a positive monotonic function of the total budget of the bureau during the bureaucrat’s tenure in office” (Niskanen, Bureaucracy and Representative Government, 1971, p. 38). In other words, the more individuals pursue their particular motives within a particular bureau, the more the bureau increases in power. Two other factors dominate the Niskanen Model which attempts to describe the relationship between the legislator and the bureaux. In this case study, the legislator demonstrates the need for a criminal tribunal and the bureau represents the external agencies involved in decision-making (CPP, UN, etc.). Niskanen describes the need for the bureau to produce a ‘maximum’ output for the legislative process, even though the inevitable outcome is that a particular bureau will provide a take-it-or-leave-it offer to the legislator. This model simultaneously advances a need for co-operation throughout a legislative process, but also a breeding ground for conflict between bureaux which seek to satisfy their own self-interested needs.

The Dunleavy Bureau-Shaping Model describes a need for a combination of, albeit ‘flawed’, welfare-maximising strategies as well as collective strategies to promote bureau-shaping. Dunleavy introduces three motivations for welfare-maximizing bureaucrats. The first motive is the placing of more emphasis on the acquisition of ‘non-pecuniary utilities’, such as prestige, influence, patronage and status (Dunleavy, 1991, p. 201). While these motivations concur with Downs and Nickanen, Dunleavy explains the need for bureaucrats to intertwine budget-maximising strategies with strategies for collective action. He proposes five collective strategies: major internal reorganisations, transformation of internal work practices, redefinition of relationships with external ‘partners’, competition with other bureaux and load-shedding, hiving-off and contracting out. These all became factors in the process towards the creation of the ECCC. Dunleavy also identifies certain bureaucrats who demonstrate this and states that “senior officials have much greater scope for exploiting individual strategies, so they are less likely to resort to collective strategies” (Dunleavy, 1991, p. 176). The higher the rank reached in a particular bureau, therefore, the greater the space to manoeuvre and to maximise individual self-interest.

Dunleavy’s second motivational factor is demonstrated by bureaucrats in the public sector seeking to prevent other officials increasing their pecuniary utilities, either by individual or by collective action, in order to divert resources to personal coffers. The third, and possibly most important, motivational factor is identified in self-interested officials who “have strong preferences about the work they want to do, and the kind of agency they want to work in” (Dunleavy, 1991, p. 202). This is expanded into several conditions which, he reasons, maybe either positive or negative (Dunleavy, 1991, p. 202):

- Positively Valued Staff Functions: individual innovative work; longer term horizons; broad scope of concerns; developmental rhythm; high level of managerial discretion; low level of public visibility

- Negatively Valued Line Functions: routine work; short-term horizons; narrow scope of concerns; repetitive rhythm; low level of managerial discretion; high level of grass roots /public visibility

- Collegial Atmosphere conditions: small-sized work unit; restricted hierarchy and predominance of elite personnel; co-operative work patterns; congenial personal relations

- Corporate Atmosphere conditions; large-sized work units; extended hierarchy and predominance of non-elite personnel; work patterns characterised by coercion and resistance; conflictual personal relations

- Central Location: proximate to the political power centres; metropolitan

- Peripheral Location: Remote from political contacts; provincial location; remote from high-status

These clearly polarized values are the issues which are debated and will be discussed throughout the dissertation. The perception of a central location, for example, is one such area of discussion. Should the ECCC have been cited at the source of the atrocities in Cambodia, with the people who have witness accounts? Or should it have been in the ad hoc International Criminal Court in The Hague, with all the necessary resources for the exercise of ‘liberal’ justice? In a study of bureau-shaping, it is Dunleavy’s assumption that the motivation of bureaucrats is the important catalyst in the development of hybrid judicial formation. It is also with Dunleavy’s more pragmatic approach in mind that I hope to examine the workings of the ECCC in their dealing with the Khmer Rouge.

My hypothesis is that individual bureaucrats of the CPP were successful in influencing the creation of their vision of the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia and yet, according to Dunleavy, they did so by promoting ‘negative’ values and moral stances that would have been unacceptable in a more liberal context.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The ultra-communist, Maoist faction of the Khmer Rouge was responsible for the deaths of 1.5 to 2 million soldiers and civilians between April 17th 1975 and January 7th 1979 (Kiernan, The Pol Pot regime: race, power, and genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79, 1996, p. 158) (Panh, 2003). These deaths were the result of a system of ethnic, political and ideological cleansing as well as torture, disease and mass starvation. Since the defeat of the Khmer Rouge by Vietnamese forces there had been several attempts to bring to justice surviving members of the perpetrators of these atrocities.

The first attempt to produce a suitable judicial mechanism came on July 15th 1979 with Decree Law 1, entitled “The People’s Revolutionary Tribunal at Phnom Penh to Try the Pol Pot-Ieng Sary Clique for the Crime of Genocide”. As this title states, the primary objective was to try Prime Minister, Pol Pot, and Foreign Minister, Ieng Sary, for the crimes of genocide. While it could be argued that this was a communist “show trial” to satisfy domestic demand, there were also representatives from the international community who were also involved with the demand, which included assigned Khmer Rouge American defence counsel, Hope Stevens, and a Japanese witness, Yasuko Naito. The trial produced various forms of evidence, including the use of 196 surviving witness accounts (Howard J. De Nike, 2011, p. 13). The conclusion of the trial was the sentencing of Pol Pot and Ieng Sary, in absentia, to be executed, and had little effect since both defendants fled to the Cambodia-Thai border where they remained for the next twenty years (Etcheson, 2005, pp. 14-17).

Other attempts at bringing the Khmer Rouge to justice have been attempted by individual states such as Australia and the US. In response to the deaths of two Australian citizens, killed by the Khmer Rouge in Tuol Sleng Prison, Australian Foreign Minister, Bill Hayden, and Australian consultant to the Department of Foreign Affairs, Gregory Stanton, first pushed for the Khmer Rouge to be tried in an ad hoc International Criminal Court in The Hague in 1986. Australian Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, however, eventually halted the initiative, through advice from the U.S. State Department (Stanton, 2003). The subsequent UN initiative of the Paris Peace Accord, signed on October 23 1991 brought the Khmer Rouge, under the name “Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea”, back into mainstream Cambodian politics. This followed the withdrawal from the country of the Vietnamese and the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC). The Khmer Rouge defiantly turned their back on a peaceful transition and were outlawed in 1994.

In the mid-1990’s, and before the beginning of the bureau-shaping process of the ECCC, the final attempts to hold the Khmer Rouge accountable for their actions were from the US Ambassador for War Crimes, David Scheffer. He attempted a U.S. prosecution of the Khmer Rouge for the murder of a US citizen in order to persuade Canada, Australia and Israel to do the same for their citizens. Amongst other proposals, he even attempted to buy Pol Pot directly from the Khmer Rouge (Etcheson, 2005, p. 156).

This is a short overview of the previous attempts that were undertaken to bring the Khmer Rouge to justice in the period leading up to June 21st 1997, when a full scale operation of negotiation and political manoeuvring began.

CHAPTER 1: The Cambodian People’s Party

In assessing the impact of individuals in the CPP on the shaping of the ECCC, it is important to understand the social and political state in which Cambodia found itself on June 21st 1997 (Ranariddh, Norodom, and Hun Sen. 1997). This was the key date on which the first official letter was delivered to the United Nations by Cambodia, calling for assistance in the formation of an international war tribunal. From this initial step towards bringing closure to the regime of the Khmer Rouge, it is possible to analyse key decisions and events to determine the extent to which individual bureaucrats influenced the formation of the ECCC.

The influence of Cambodian politics on the development of the ECCC before June 21st 1997 cannot be overstated. Unlike the international war tribunals that were set up in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, Cambodian atrocities had occurred 18 years before the setting up of international war tribunals were even a possibility. In that period, Cambodia had, to some extent, recovered, metamorphosing into a pluralistic political structure. In essence, Cambodia had been given the opportunity to stand on its own two feet and this vacuum allowed various powers to take control (Kiernan, The Pol Pot regime: race, power, and genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79, 1996). May 23rd 1993 marked the first peaceful election since the pre-Khmer Rouge era. The results gave a 45% majority to the National United Front for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful, and Cooperative Cambodia (FUNCINPEC), led by Prince Norodom Ranariddh. The CCP won 38% of the votes and was led by Hun Sen (Gottesman, 2003, p. 352). This caused an unsettling dual-government relationship, which was highlighted by the failed CPP coup d’état in July 1994. The incident caused Ministry of the Interior members Sing Song and Sin Sen to flee to Thailand, having succeeded in demonstrating the actual and potential power of the CPP. This would later become manifest in a full government takeover in July 1997. Evan Gottesman states that it was in this period that individual officials became increasingly motivated by personal advancement. He writes, “FUNCINPEC officials were more concerned with satisfying their superiors than with changing the way the country was governed” (Gottesman, 2003, p. 353). This is absolutely critical in determining the significance of individual bureaucrats in Cambodia and the power they wielded.

In their everyday life, Cambodians still bore the scars of the Khmer Rouge era. In a questionnaire from The Centre of Social Development to 632 people, 91% rejected the proposition that there be no trial of former Khmer Rouge leaders and 82% believed that the trial of Khmer Rouge leaders would be advantageous to national reconciliation (Fawthrop & Jarvis, 2004, p. 144). A further statistic of popular opinion was that 51% of voters believed that all regimes, both before 1975 and after 1979, should be brought to trial. This included the ‘regimes’ of the United States and of China. The statistic, of course, would have had unimaginable domestic and international ramifications if such justice were exacted. It was generally considered that trials would also be necessary to challenge the ‘culture of impunity’. Without answering the crimes of the Khmer Rouge, we can say, with Etcheson, that anarchy in Cambodia will remain a threat due to the excuse that ‘the Khmer Rouge were worse’ (Etcheson, 2005, p. 171). These figures and analyses are relevant to the examination of the actions of the CPP in the development of the ECCC and in the consideration of whether these actions appropriately reflect collective opinions and not simply the opinions of individuals.

In the CPP, Prime Minister Hun Sen and Cambodia’s chief negotiator Sok An were the two bureaucrats who had the most influence in the formation of the ECCC from a Cambodian perspective and, from analysing events that involved them, it is possible to determine the amount of personal influence they had, as well as the areas they influenced the most, whether positively or negatively.

Hun Sen’s impact on the negotiations during the shaping of the ECCC was critical. On September 20th 1999 at the 54th UN General Assembly, Hun Sen delivered a document to Secretary-General Kofi Annan which proposed three possible courses of action with United Nations involvement: to provide a legal team and participate in tribunal activity in Cambodia’s existing courts, to provide legal advice without direct participation, or to withdraw completely from the tribunal (Ehrisman, 2013, p. 33). This document is key in revealing Hun Sen’s individual preference for minimal international involvement and for the maintenance of his own power. By minimising international co-operation, bureaucrats would be able to influence judicial members and exercise their power and prestige without the risk of reprisals. Even in October 2002, evidence surfaced that Cambodian judges regularly had to pay 30 percent of their salary to bureaucrats in order to keep their jobs (Pike, 2002). If this were to become a feature of a Khmer Rouge tribunal, it would demonstrate negative values by creating a low level of managerial discretion, conflicting personal relations and, without international judges, extending the hierarchy and predominance of non-elite personnel.

Hen Sun’s call for Cambodian control of the ECCC in 1999 was not just an isolated feature of negotiations with the UN. As Prime Minister, he would publicly issue statements, as in December 1998 that: “…we should dig a hole and bury the past and look ahead to the 21st century with a clean slate” (Ciorciari, 2009, p. 66). This was not abnormal. Rama Mani stated that, in previous years, the CPP, Hun Sen in particular, refused to exhibit any genuine political will and often manipulated the judiciary (Mani, 2002, p. 72). A government meeting in February 2000 offers the clearest indication of non co-operation. Hun Sen addressed an anti-tribunal cadre telling them that there was “no need to worry about the tribunal, because he has successfully stalled progress on the negotiations… he would continue to stall the international community until all the key suspects had died of natural causes.” (Etcheson, 2005, p. 163). While Sen’s statements from the UN and from multiple news sources do suggest individual bias, the fact that Hun Sen used such radical statements in the midst of anti-tribunal factions suggests that elements within the CPP held considerable political power, with radicalised views against international co-operation. The strength of these views should be set against the statistic that showed an overwhelming popular need for a trial in order to reconcile the past. The CCP and Hun Sen, however, faced criticism from the opposition Sam Rainsy Party and international NGOs, and risked a high level of international visibility and the possibility of alienating aid and finance from international actors and investors. This, in turn, would prove costly as, “wealth accumulates in the hands of officials, generals and a few big businesspeople” (Gottesman, 2003, p. 357). The Prime Minister continued to highlight the nature of the top-down rule of the CPP and his own authoritarian role, while dominating negotiations with the United Nations which he used as a means of maintaining domestic political power.

The second prime mover with a considerable role in these negotiations was Sok An, known by many as the “minister of everything”. As head of the Cambodian Task Force in the Khmer Rouge Trial, he was prominent in drafting key laws, none more significant than the ‘Establishment of Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia for Prosecuting Crimes Committed during the Period of Democratic Kampuchea’. The fact that Sok An had multiple roles within the CPP, including Chairman of the Council for Demobilization of Armed Forces, Chairman of the National Tourism Authority of Cambodia and Chairman of the Council for Public Administrative Reform, to name but a few, illustrates two factors: firstly, that the lack of a division of labour in ministerial posts diminishes the actuality of democracy pertaining to that state, and, secondly, it appears that the CPP is driven by an elite subgroup of self-interested bureaucrats. Fawthrop and Jarvis describe how this lack of distribution of power was problematic in negotiations as “all important decisions are still made by a few people at the top… Sok An, the chairman and chief negotiator from the Cambodian side, was reportedly at the same time holding down no less than 47 other portfolios.” (Fawthrop & Jarvis, 2004, p. 187). On the other hand, Sok An was the most influential member of the CPP in the drive for the completed ECCC Law which was finalised on the June 6th 2003. On multiple occasions, Sok An showed willingness to continue to co-operate with the UN after they withdrew from negotiations in January 2002. Examples of this include his letter of January 22nd 2002 and his reference to Articles 26 and 27 of the Vienna Convention of the Laws of Treaties as common ground for the combining of both the “Establishment of Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia for Prosecuting Crimes Committed during the Period of Democratic Kampuchea” and the UNGA Resolution of December 2002. (Fawthrop & Jarvis, 2004, p. 200). This demonstrates a commitment to the development of a bureau dedicated to positive values such as: co-operative work patterns with the United Nations, the conferring of high-status social contracts and the establishment of a specialised war tribunal judiciary with longer-term horizons and a broad scope of concerns.

Because, every year, the need for a war-crime judiciary dwindles, as the Khmer Rouge generals die off, and as the need for international NGOs and voluntary associations is recognised, individual powers in Cambodia continue to influence the way that the bureau is shaped and possibly manipulated, with personal ambition and gain still predominating.

Individual actors within the United Nations were vital in the conception of the ECCC, but less so in the latter stages of the negotiations. It is important to stress that, while the United Nations is a congregation of 196 members, in this chapter I will be examining the individuals that held specific United Nation posts. The key bureaucrats are: Thomas Hammarberg, The UN Group of Experts, Han Corell and Kofi Annan. Before evaluating these individuals, it is important to examine the history of the role of the UN in Cambodia and its capacity to build bureaux for the protection of human rights.

The UN’s failure to assist in the trials of the Khmer Rouge can best be summed up in Thomas Hammarberg’s report of April 22nd 1999: “Twenty years ago, this Commission received a report on the mass killings and other large-scale atrocities in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge regime. There was, however, no real discussion of the report and no resolution was passed” (Hammarberg, Presentation to the UN Commission on Human Rights by Thomas Hammarberg, the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Human Rights in Cambodia, 1999). While this lack of interest can, to some extent, be attributed to Cold War politics and since Cambodia was still very much a political pawn, the UN was heavily criticized for not exercising its international powers. Not only did the UN fail to recognise the reality of genocide but they also allowed the Khmer Rouge to represent Cambodia in the UN until the 1991 Paris Peace Agreement which launched a fundamental realignment of Cambodian politics. This said, the UN’s failures were largely a combination of separate state influences. This will become a significant issue in the next chapter.

The timing, in 1997, of the UN intervention in Cambodia to develop an international tribunal is not surprising. The Rwandan genocide in 1994 and the on-going Yugoslav conflict from 1991 to 1999 triggered The Rome Statute at a diplomatic conference on July 17th 1998. This was convened to extend international law to hold individuals accountable under international law at an ad hoc International Criminal Court in The Hague. Cambodia was seen as a perfect proving ground for the practice of international law by this method, and it will become a pivotal factor in the discussion of the UN’s Group Of Experts, Hans Corell and Kofi Annan.

Thomas Hammarberg’s contribution, as the second UN Secretary General Special Representative of Human Rights in Cambodia, is critical. This was because he was one of the first international figureheads to acknowledge the effect that the Khmer Rouge genocide still had on Cambodian society. As he said, in a statement in 2001, about his initial appointment in 1996: “One message becomes clear: the crimes were not forgotten. Almost everyone I met was personally affected, had suffered badly and/or had close relatives who died… the overwhelming majority wanted those responsible to be tried and punished” (Hammarberg, Special Insert: Efforts to establish a tribunal against KR leaders, 2001). This recognition of the psychological stranglehold which the Khmer Rouge still had on Cambodian society caused Hammarberg to exercise his personal influence which, in turn, set off a chain reaction: “I suggested informally during the UN Commission on Human Rights session in April 1997 that a paragraph be included in the Cambodia resolution. The paragraph should mention the possibility of international assistance to enable Cambodia to address past serious violations of human rights” (Hammarberg, Special Insert: Efforts to establish a tribunal against KR leaders, 2001).

As the UN Secretary General Special Representative of Human Rights, his liberal position came as no surprise. Hammarberg had been a former executive director of Amnesty International, the primary objectives of which are based around the dissemination of information about human rights and the support of the individual to “challenge and enable people to take action and demand, support and defend human rights and use human rights as a tool for social change” (Amnesty International , 2014). In turning this philosophy into practical governance, Hammarberg, in June 1997, along with UN human rights officers David Hawk, Brad Adams and Christophe Peschoux, became catalysts in persuading co-Prime Ministers Hun Sen and Norodom Ranariddh to sign the letter to the UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, which would call for a hybrid Khmer Rouge tribunal (Etcheson, 2005, p. 160). While Hammarberg lacked a ‘forceful hand’ to shape the ECCC, he provided an ideological platform and ignited the bureau-shaping mechanisms essential to the creation of the ECCC through his historical background and his individual influence. The practicalities and details would inevitably be left to the UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan and his ‘Group of Experts’.

Commissioned by the UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, in accordance with the December 12th 1997 Resolution 52/135 entitled “Situation of Human Rights in Cambodia”, the Group Of Experts revealed information, the importance of which cannot be overstated. Without their reports, the UN would not have been able accurately to negotiate past ideological roadblocks in Cambodian society nor be able to introduce an international form of liberal peace. The Group of Experts included: the former Governor-General of Australia and judge in the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), Ninian Stephen, a further judge of the ICTY, Muritian Rajsoomer Lallah and the UN Human Rights committee member, American Steven Ratner. These three individuals effectively symbolized international justice as representatives of three separate continents, whilst also being specialists in the fields of international criminal bureau-shaping. From July 1998 to February 1999, the Group of Experts investigated the practicalities of forming an international criminal court for trying the crimes of the Khmer Rouge. While agreeing that the tribunal should be limited to ‘those most responsible’, their recommendation advanced the notion of an ad hoc international tribunal with features similar to other on-going international tribunals. The installation of a Rwanda-like ‘truth-telling’ mechanism and the inclusion of the same Prosecutor from the ICTR and ICTY tribunals were among the proposals (Stephen, Lallah, & Ratner, 1998). While this appeared to maximise the influence of a UN-driven criminal court, however, the Group Of Experts suggested neutral territory for the court by granting it a location within South-East Asia. This seems logical, since it granted access to vital evidence without the need to transport material over vast distances, whilst maintaining a discreet separation from CPP influence.

The most profound recommendation by the Group Of Experts was the setting up of a full panel of judges appointed by the UN which would exclude any Cambodian judiciary influence. Steven Ratner cites four specific reasons for their recommendation: the inadequacy of the Cambodian legal framework, the lack of Cambodians in the legal profession, the deplorable state of legal infrastructure, such as prisons and reform institutions, and, lastly, the Cambodian culture of lack of respect for any impartial criminal justice system (Ratner, Abrams, & Bischoff, 2009). These were certainly factors that hindered Cambodia’s apparent right to exercise domestic justice, but the recommendation to provide a pure ad hoc international criminal trial was fundamentally flawed. By removing Cambodian influence in the ECCC, Cambodia lost any sense of ownership, any attempt to increase knowledge of international judicial standards and also any chance of reforming its own judicial sector which had been yet another victim of the Khmer Rouge regime. At this stage, it would have been possible to push for hybridity in the ECCC which “may be more likely to be perceived as legitimate by local and international population because they both have representation on the court” (Dickerson, 2003, p. 310) but this was not considered by the Group of Experts who continued to report their attempts to grant practical, short-term solutions in exacting international justice. In terms of individual bureaucratic gain, with Ninian Stephen and Rajsoomer Lallah’s previous experience of being judges in the ICTY, it could have been feasible that the promotion of an ad hoc trial would also improve their future career prospects in a move from the ICTY to the ECCC. However, an ad hoc tribunal was widely considered the norm and was unanimously supported by human rights NGO’s such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International (Fawthrop & Jarvis, 2004, p. 168). In conclusion, the report failed to consider the opportunity to extend a long-term administrative advancement in judiciary reform for a country that lacked unbiased and organised courts. On the other hand, the report directly addressed the most effective process for “Cambodia to move away from its incalculably tragic past and create a genuine form of national reconciliation for the future” (Stephen, Lallah, & Ratner, 1998). The report was a pivotal starting post in the negotiations with Kofi Annan and Hans Corell in the period between 1999 to 2003.

Hans Corell, former Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs and the Legal Counsel for the United Nations, was instrumental in using the Group Of Experts’ report and in assisting in the amendment of multiple Cambodia draft laws which were key in the negotiations with the CPP. Corell’s previous experiences as Ambassador and Under-Secretary for Legal and Counsel Affairs in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 1984 to 1994 put him in an ideal position to influence the shaping of the ECCC after the Cambodian government rejected the Group Of Experts’ recommendations. On December 23rd 1999, Corell, along with his legal deputy H.E. Ralph Zacklin, mapped out certain provisions which were considered essential for inclusion by the UN in the negotiations. These included: the requirement of an international majority of judges, the reorganisation of the composition of the court, as well as a reassessment of the roles of co-prosecutors and investigatory judges. These concerns had been reflected in several ‘Non-Papers’ (informal messages) of which one was sent to Kofi Annan on January 5th 2000. This message suggested that “…the United Nations could be accused of assisting what many would describe as a sham trial” (Fawthrop & Jarvis, 2004, p. 164). The fallout from such an accusation would cause further mistrust between the UN and the Cambodian parties and, as Tom Fawthrop wrote, “This Non-Paper-quintessential Hans Corell-was a defining moment in what was from the onset a marriage of convenience, in which neither groom or bride understood or trusted each other” (Fawthrop & Jarvis, 2004, p. 165). This is perhaps a perfect example of the intransigence of the UN in their programme of promoting their vision of international justice without attracting the label of the next “League Of Nations”. Negotiations between Corell and the Cambodian government were to continue, with trepidation, on both sides. Corell left Phnom Penh on 7th July 2000 in the belief that an understanding had been reached on the outcome of the negotiations. This understanding would grant greater respect to the proposals of the Group Of Experts and would include these recommendations:

Cambodian majority of judges at all levels of the court, but moderated by the requirement for a “super-majority” requiring at least one of the foreign judges to participate in any judgment; each side was to have an autonomous prosecutor and investigating judge who were to have equal status, and a mechanism (a pre-trial chamber) had been devised to resolve any disputes between them; the tribunal was to follow Cambodian procedure, with the possibility of drawing from international procedure in cases of lacunae; its jurisdiction would involve both domestic and international law; and the government had written into the Draft Law a commitment not to seek any pardons or amnesties (Jarvis, 2002, pp. 608-609)

Corell found himself at the centre of a dispute in which he felt that the Cambodian parties were attempting to adopt double standards on numerous issues and were failing to acknowledge the UN as equal partners. Finances were one of these thorny issues. The ICTY and the ICTR accounted for $100,000,000, or 15% of the UN budget, a year (Nouwen, 2006, p. 191). Corell raised the issue of financial assistance on multiple occasions and made it clear that he would not approve the full financial assistance of the ECCC by the UN unless the UNs demands were met. As with the concept of a hybrid court, there would be a sharing of the financial load. From a letter from Minister Sok An on January 22nd 2002 and after the Cambodian government had brought the ECCC draft law to parliament without the consent of the UN, Corell came to the conclusion, “that the Extraordinary Chambers, as currently envisaged, would not guarantee the independence, impartiality and objectivity that a court established with the support the United Nations must have.” (Corell, Daily Press Briefing by the Office of the Spokesman for the Secretary-General, 2002). Corell orchestrated the subsequent withdrawal of the UN from legal negotiations on February 8th 2002 in response to a lack of agreement and communication. But, by maintaining a firm stance on the upholding of international law, he also kept the UN’s worldwide reputation intact. Kofi Annan would become the leading figure in the negotiations on behalf of the UN from February 2002 to June 2003.

UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan was not only a grassroots actor in the negotiations, but his individual influence was crucial. As holder of this high office, Annan’s role was to be a spokesman for the oppressed and deprived whilst maintaining his perceived role as an independent, impartial figure of integrity (The United Nations, 2012). He was the main channel of communication in the turbulent negotiations, which began with Hun Sen’s letter of demands in September 1999 but grew with the UN withdrawal in February 2002 and proceeded to the inception of the ECCC in June 2003. All UN decisions went through Annan and he used Corell’s ‘Non-Paper’ in a letter of February 8th 2000 which included the rejection of previous amnesties and the guaranteed arrest of those deemed to be most responsible. Annan’s deepest concerns were the corruption of the Cambodian judiciary and, through his own experience with the early negotiations with the Cambodian government, his recognition that they had not demonstrated the active commitment to the creation of the ECCC. This would be essential when it came to implementing any agreement. This would also be critical in establishing a future court and getting it up and running and making sure that it ran efficiently and expeditiously (Corell, Justice for the Killing Fields: Re-negotiating the Khmer Rouge Genocide Court for Cambodia , 2003).

The eventual breakdown of communications in February 2002 prompted Annan’s most significant decision which was to resist total withdrawal from ECCC negotiations, even when his legal advisors, Hans Corell and Ralph Zacklin, advised against this. Craig Etcheson suggests that this was primarily due to past UN failure to protect the people of Rwanda in 1994 (Etcheson, 2005, p. 161). Annan was not afraid to discuss past failures, with suitable and sincere regret, whilst proposing their use as building blocks for the reform of future international justice systems:

The United Nations association with the worst atrocities of recent civil wars was a terrible stain on the organisation. But this (Rwanda) was a painful reminder that we could use: a shock to us all that we could turn into a productive and powerful instigator of reform (Annan & Mousavizadeh, 2012).

In a pivotal meeting with a Cambodian delegation headed by Sok An on January 6th 2003, Annan, driven by past failures and with a personal vision to reform, undermined Corell’s idea of an international majority court and was prepared to sacrifice the concerns of the UN delegation in order to form a Cambodian majority court with fewer Khmer Rouge figures on trial. Many NGOs, including Amnesty International and Asia’s head of Human Rights Watch, Brad Adams, have criticized this decision. Adams said that: “No one in the U.N. or elsewhere will ever copy the Cambodian model… It’s the lowest standard the United Nations has been willing to go” (Brady, 2009). On the other hand, it is possible that, without the UN agreement to sacrifice a few of these conditions, Cambodia would have formed their own domestic tribunal outside the parameters of international law which, in turn, would have undermined the UN, which was in the midst of trying to establish a criminal court in Sierra Leone. Annan’s actions ensured that the UN still had a significant representative role in the ECCC, while the credibility of international law remained intact.

Hammarberg and Annan symbolized the humanitarian branch of the UN. Hammarberg created the initial platform on which the UN could negotiate with Cambodia. Annan, while a major figure throughout the seven years of negotiations, was instrumental in regaining the confidence of the Cambodian Government whilst keeping many of the UN’s essential conditions intact. The importance of the Group of Experts and of Hans Corell are, however, somewhat undervalued. The Group of Experts’ investigation and report was a turning point, since it gave the UN a strategy for combating the Cambodian ‘culture of impunity’ and corruption. Without the Group of Experts’ report and thorough investigation, the UN’s role could easily have been deflected to support a trial which would have been considered ‘sham’ by international standards. Hans Corell spearheaded the legal opposition to the Cambodian counter proposals and it was this which propelled him into being possibly the most significant actor in the UN’s fight to shape the bureau that would become the ECCC. Without Corell’s practical, unrelenting determination to produce a trial incorporating equal levels of influence and to keep open a clear line of communication between Cambodian officials and Annan, it could be argued that Cambodian officials would have been in a position to exercise total influence over the ECCC today, thus undermining the authority of the UN in what could be one of the most damaging and dangerous political failures of the 21st century.

CHAPTER 3: Individual States

The Khmer Rouge and their atrocities had worldwide significance. Until 1991, and because of Cold War geo-politics, the Khmer Rouge was acknowledged as the international representative of Cambodia and, as such, had important political leverage. On four separate occasions, Western powers voted against the removal of the Khmer Rouge from their seat in the UN (Gottesman, 2003, p. 44). While the death toll of international citizens between 1975 and 1979 must have been considerable, the exact figure is unknown. The only foreign death indications are from the records at S-21 Tuol Sleng Prison where 79 foreigners were killed: 1 Arabian, 4 Americans, 2 Australians, 1 Briton, 3 French, 6 Indians, 1 Javanese, 1 Laotian, 1 New Zealander, 28 Thai and 29 Vietnamese (Documentation Center of Cambodia, 1999). Even in the build-up to the negotiation process of the ECCC, between 1994 and 1998, ten foreign workers were killed by the Khmer Rouge, including Christopher Howes, a UK citizen for a British NGO Mines Advisory Group (MAG) in March 1996 (Hyslop, 2011). It is clear, therefore, that many countries had an interest in the progress of the hybrid initiative of the UN.

The contribution of individual states to the ECCC was most conspicuously in the form of financial aid. With an estimated ECCC budget of $56 million, international donors were expected to pay $43 million (Ciorciari, 2009, p. 78). By December 2013, Japan had donated the greatest amount with 42% of the total, while Australia contributed 11%, the USA 11%, Germany 6% and the United Kingdom 6% (ECCC Budget and Finance Offices, 2013). To understand the influence of bureaucrats within states beyond the jurisdiction of the UN presents a significant challenge. Whereas the individuals within the CPP and the UN formed part of a clearly defined hierarchy with purpose and direction in the process of bureau-shaping, the bureaucrats from other various states have motivations that encompassed both international and domestic issues. This made the identification of individuals and their motives in bureau-shaping outside the state they are representing, particularly difficult. The states and bureaucrats that were most influential in these negotiations were: the United States of America and China.

Because of its powerful international role in the recent past, the US’s involvement in the bureau-shaping process was curious to say the least. The US was partly responsible for the rise of the Khmer Rouge since they had, themselves, launched a mass bombing campaign on Cambodia from 1970 to 1975 which killed thousands. In the 1980’s, the USA, still in the midst of Cold War geo-politics, developed a programme to support the Khmer Rouge and they reduced domestic coverage of their brutality. Such tactics included providing the Khmer Rouge with $12 million dollars worth of food. The 1980 CIA report stated that the Khmer Rouge stopped murdering people in 1976 and simply covered up the deaths of at least 500,000 Cambodians. According to Prince Norodom Sihanouk’s intelligence reports, the CIA was training the Khmer Rouge in Thai camps in order to overthrow the Vietnamese-backed Hun Sen government (Kiernan, The Cambodian Genocide and Imperial Culture, 2005). Despite this chequered record, the US would be seen as a third unofficial significant party (the others being the CPP and the UN) from the beginning of the negotiations. Two major events swung the position of the US: on April 30th 1994, the US passed the Cambodian Genocide Justice Act which guaranteed US support for the bringing to justice of members of the Khmer Rouge for their crimes against humanity between April 17th 1975 and January 7th 1979. The second event, in November 27th 1997, was when Hun Sen and the Cambodian Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Co-operation, Ung Huot, sent US President Bill Clinton a letter requesting support: “The Royal Government of Cambodia would be most grateful to the United States government if help could be provided, according to US laws, to set up an international criminal tribunal and to bring to trial the Khmer Rouge leadership while they are still alive…” (Scheffer, 2008, p. 3). This was very well received and the US suggested numerous forms of infrastructure for the setting-up of the ECCC. The first suggested form was made public on April 28th 1998 in the US government spearheaded draft UN Charter Chapter VII which aimed to establish the International Criminal Tribunal of Cambodia (ICTC) in The Hague (Scheffer, 2008, p. 3). The ICTC method would present significant advantages for the USA. A court in the similar vein as the ICTY and the ICTR would continue the advancement of a new worldwide order under the banner of fair justice and democracy, as well as denouncing the International Criminal Court which had been seen as a threat to USA sovereignty with its accusation of US judicial influence (Etcheson, 2005, p. 157). Institutions from within, or funded by, the US, such as Yale University’s Cambodian Genocide Program and the Documentation Centre of Cambodia (DC-Cam), held a significant amount of documentation and statistics that would be critical in any form of judicial mechanism, and so the US held a considerable amount of political leverage. The individuals assigned to the representation of the US’s interests in the development of the ECCC consisted of a mass of officials and specialists and, most notably, USA Senator, John Kerry, and the US Ambassador of War Crimes, David Scheffer.

While the US Senator for Massachusetts, John Kerry, gave a much documented and much disputed account of Cambodia in his “Christmas in Cambodia” in 1968 (The Washington Post, 2004), he was a bureaucrat who had had first hand experience of the confusion of the Vietnam War which triggered the events of the emergence of the Khmer Rouge. He was a credible overseer of US interests, while understanding the complexities of developing the ECCC. Working alongside David Scheffer, Kerry’s most significant influence on this operation would be his proposal of a ‘hybrid panel of judges model’. He set out a mechanism, later utilised by UN officials, by which there were to be three Cambodian judges and two foreign judges on the judicial panel and any decision could only be made with four consenting votes. This would ensure a ‘super-majority’ with neither Cambodian nor international judges gaining dominance from within the ECCC. This was agreed upon by Hun Sen on April 29th 2000 and would trigger similar hybrid models elsewhere, specifically with co-investigating judges and co-prosecutors. As opinion moved away from the initial US proposal of an ad hoc tribunal, support shifted to the hybrid model which revealed a clear desire not to deny Cambodia a degree of sovereignty as well as guaranteeing unequivocal commitment to a programme of reparations. As individual bureaucrats, both Kerry and Scheffer found themselves often taking the role of a catalyst in the negotiations between the CPP and UN, a role which was critical, not only on an international level, but on the US domestic level, just as the Bush Administration was coming into power. Craig Etcheson comments on this: “During the last years of the Clinton Administration, the OLA (Office of Legal Affairs) was deluged with practically daily calls and meetings about the Khmer Rouge tribunal from senior US officials. In contrast… (there were) only two calls from Washington about the tribunal during the first two years of the Bush Administration” (Fawthrop & Jarvis, 2004, p. 184). With the impending change of US foreign policy, the individual influence of Kerry, Scheffer and other US bureaucrats on the speeding up of the bureau-shaping process of the ECCC, such as the provision of deadlines on a UN-Cambodia agreement on the June 15th 2000, cannot be overstated (Stephen Heder, 2001). On the other hand, John Ciorciari would acknowledge that, as US domestic issues reduced their interest in the ECCC, the US under the Bush Administration had inadvertently “created uncertainty about where the real bargaining authority lay.” (Ciorciari, 2009, p. 80).

China’s connection to the Khmer Rouge was, arguably, just as eccentric and indefinable as the US’s had been. On September 30th 1976, a Khmer Rouge revolutionary, Keav Meah, said: “The greatest friend of the Kampuchean people is the People’s Republic of China” (Mertha, 2014, p. 1). China’s history of aid to the Khmer Rouge had been directly influenced by the sour relations between China and Vietnam. A 1977 Khmer Rouge report showed that China had shipped thousands of tons of military hardware, including fighter jets, ammunition and communication equipment, to Cambodia (Nhem, 2013, p. 51). Yet the assistance in arms would be only one of many forms of support that China would give the Khmer Rouge. There is no doubt that this was a Chinese form of geo-politic initiative designed to apply political pressure on Vietnam on two geographic fronts. However, for the citizens of Cambodia, this would have deadly consequences. Since the collapse of the Khmer Rouge, China has denounced any involvement with them and, even to this day, Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia, Zhang Jinfeng, maintained, on December 22nd 2010: “The Chinese government never took part in or intervened into the politics of Democratic Kampuchea”. These denials shaped their baleful influence on the development of the ECCC.

China provided a substantial obstacle to the assistance provided by the US and did all they could to block the development of the ECCC. Chinese bureaucrat, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhu Bangzao, said on November 7th 2000: “It should be up to the Cambodian people to decide without foreign influence… China has not and will never apply pressure on the Cambodian government over this question” (Bangzao, 2000). To say, however, that the Chinese lacked any particular influence in the ECCC is false. The Human Right Watch 2000 report confirmed that, in June 1999, Chinese Foreign Minister Tang Jiaxuan lobbied Cambodian officials to resist any form of international involvement in the ECCC (Human Rights Watch Staff, 2000, p. 178). Thomas Hammarberg also comment on this relationship, saying: “The Chinese were actively working against any further UN initiative. In a meeting with the Chinese Ambassador in Phnom Penh, he argued that the issue of the Khmer Rouge was an ‘internal’ matter…” (Fawthrop & Jarvis, 2004, p. 179). Various Chinese bureaucrats typically followed the party lines of publicly denying interference but then exercising influence behind closed doors. It can be assumed that the Chinese were unwilling to develop an internationalized, hybrid criminal court, as this would unearth their previous affiliations with the Khmer Rouge. To bring these affiliations to an international criminal court would have had a profound effect on China’s increasing political influence and reputation in the world arena. While this lobbying was certainly an issue in the early development of the ECCC, Chinese interference dwindled as soon as it was agreed that numbers being tried in the ECCC were between 5 to 10 Khmer Rouge and no international defendants.

In conclusion, the US played a key role by being the diplomatic catalysts, as personified by John Kerry and David Scheffer, in a sensitive and complicated international negotiation. The inauguration of President Bush, on January 12th 2001, inevitably shifted the focus of US foreign policy and reduced their influence in the ECCC. As for China, its bureaucratic influence followed domestic party lines in an attempt to conceal past affiliations which could have affected its burgeoning powers on the international scene.

CONCLUSION

To determine whether the negotiation for the ECCC provided a platform for a successful bureau, it is important to reintroduce Patrick Dunleavy’s bureau-shaping model. Dunleavy states that senior bureaucrats wield the largest influence during the inception and creation of public policy. The main section of the dissertation has already identified those senior powerful bureaucrats, but whether their influence created a ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ bureaucracy, according to Dunleavy, is an area that will be discussed in this conclusion. It is important, firstly, to establish which bureaucrats had their primary initiatives included in the final June 6th 2003 ECCC Law, in order to determine the level of influence which they had on the development of the ECCC (Royal Government of Cambodia and the United Nations, 2004).

| Group | Bureaucrat | Initial Initiatives | ECCC Law: Successful/ Unsuccessful |

| CPP | Hun Sen | · Proposed to the UN: 1) A legal team and participation in tribunal activity in Cambodia’s existing courts. 2) Legal advice without direct participation. 3) Withdrawal completely from the tribunal. | Unsuccessful |

| · Proposed to minimise Khmer Rouge defendants. | Successful(Chapter 2) | ||

| Sok An | · Set out Cambodian majority hybrid tribunal within Cambodia boundaries. | Successful(Chapter 3) | |

| UN | Thomas Hammarberg | · Fostered diplomatic relationship between the CPP and UN. | Successful |

| Group of Experts | · Counter-proposed Ad hoc international tribunal without Cambodian judiciary | Unsuccessful | |

| · Location within South-East Asia. | Unsuccessful | ||

| Hans Corell | · Required an international majority of judges. | Unsuccessful | |

| · Suggested reorganisation of the composition of the existing court. | Successful (Chapter 10) |

||

| · Sought the reassessment of the roles of co-prosecutors and investigatory judges. | Successful(Chapter 6 and 7) | ||

| · Pursued equal levels of funding from the CPP and international sources. | Unsuccessful | ||

| Kofi Annan | · Cancelled previous amnesties and pardons for Khmer Rouge members facing charges of crimes against humanity and genocide. | Successful (Chapter 12) |

|

| · Attempted to increase the number of Khmer Rouge defendants. | Unsuccessful | ||

| · Proposed the appointment of single independent international prosecutor and single investigating judge. | Unsuccessful | ||

| · Proposed majority of international judges, to be appointed by the Secretary-General. | Unsuccessful | ||

| Individual States | US | · Constructed and laid out supermajority judiciary mechanism (John Kerry). | Successful(Article 9) |

| · Proposed tribunal outside the ICC but at The Hague. | Successful(Chapter 14) | ||

| China | · Proposed Cambodian tribunal with no international influence. | Unsuccessful |

This table goes some way towards creating a picture in which the initiatives of bureaucrats became part of the fundamental construction of the ECCC and which, in turn, indicates their overall influence on the progress and the results of the ECCC. However, it will take the discussion of their specific goals, under the guidelines of Dunleavy, to determine whether the ECCC, from its inception in the years from 1997 to 2003, has developed a reasonable chance to succeed. In terms of bureau-forming successes and failures, it is often difficult to pinpoint the exact causes and effects and, in the case of the ECCC, the number of actors and agencies involved make accuracy even more elusive. Dunleavy’s categorization of positive and negative values is helpful in the tabulation of the organisational features of bureaux (Dunleavy, 1991, p. 202):

Staff versus Line Functions

- Positive Valued Staff Functions: individual innovative work; longer-term horizons; broad scope of concerns; developmental rhythm; high level of managerial discretion; low level of public visibility

- Negatively Valued Line Functions: routine work; short-term horizons; narrow scope of concerns; repetitive rhythm; low level of managerial discretion; high level of grass roots/public visibility

In establishing which bureaucrats were instrumental in developing positive Staff Functions, those in the UN undoubtedly pushed for all such positive values, especially when mapping out a broad scope of concerns which could have plagued the ECCC. The Group of Experts’ report was able to highlight Cambodian domestic problems, from the corruption of Cambodian bureaucrats in the judicial sector to the substandard infrastructure which would have simultaneously undermined the legitimacy of the tribunal while leaving domestic judiciary standards unchanged. The antithesis of this group was represented by Hun Sen who suggested minimal, ageing defendants and an all-Cambodian judiciary advocated short-term goals and a narrow scope of concerns which would, indeed, “dig a hole and bury the past” (Ciorciari, 2009, p. 66). In all of this, it should not be forgotten that Han Corell, although some of his proposals proved unsuccessful, was an important influence on the establishment of ‘positive’ staff functions and by his example, on strict moral standards (Dunleavy, 1991, p. 202):

Collegial versus Corporate Functions

- Positively Valued Collegial Functions: Small-sized work unit; restricted hierarchy and predominance of elite personnel; co-operative work patterns; congenial personal relations

- Negatively Valued Corporate Functions: Large-sized work units; extended hierarchy and predominance of non-elite personnel; work patterns characterized by coercion and resistance; conflictual personal relations

The bureaucrats who advocated a positive collegial atmosphere were those who represented China, including Foreign Minister, Tang Jiaxuan, who petitioned and lobbied against any form of hybrid tribunal. Whilst the idea of a hybrid tribunal is supposed to be a synthesis of the positive aspects of separate entities, hybridity inevitably leads, according to Dunleavy, to a negative corporative atmosphere. US Senator John Kerry’s initiative to install a judging panel of three Cambodian judges and two international judges, where decisions might only be established with a super-majority, might create work patterns which would be characterised by coercion and resistance because of the conflicting interpretations of Cambodian and international law. The result could very well lead to conflicting personal relations on account of the standstills and time wasting in court proceedings. Kerry’s initiative, however, forms Article 9 of the finalized ECCC Law (Royal Government of Cambodia and the United Nations, 2004) which was accepted by both CPP and UN parties after negotiations and which highlights the level of influence of the US bureaucrats. However, Kofi Annan recognised this and fought to reduce the level of hybridity by attempting to appoint a single independent international prosecutor and a single investigating judge. The corporate triumphed over the collegial, even though Dunleavy classes the collegial atmosphere as being ‘positively valued’ and necessary to the running of a successful bureau. In the end, all bureaucrats in the CPP, UN and the US pushed for the corporate atmosphere option against the collegial aspirations of China. In their desire to close the process to international interference and to promote a single entity tribunal, the Chinese bureaucrats supported the positively valued collegial atmosphere which was the only one that could have succeeded in the long run. Hybridity, then, this “judicial romanticism”, depended on a delicate balance of powerful opinions and, as such, needed the support of large work units and an extended hierarchy. Geography also played a part (Dunleavy, 1991, p. 202):

Central versus Peripheral Location

- Positive Valued Central Location: Proximity of the political power centres; metropolitan

- Negatively Valued Peripheral Location: Remote from political contacts; provincial location; remote from high-status influence

The choosing of a bureau location is generally more subjective then rational. John Kerry, David Scheffer and the U.S. delegations’ suggestion of the ECCC to be centred on the ICC in The Hague has particular advantages, as it already had the necessary personnel, resources and political contacts to initiate a tribunal. On the other hand, while a large quantity of documentation which would be vital to the tribunal had been archived in DC-Cam at Yale University, a court in Europe would alienate Cambodian residents and those most affected by the atrocities who could provide vital witness accounts of the crimes between 1975 and 1979. While the Group of Experts’ idea of a court in an undisclosed location within South-East Asia attempted to satisfy this concern, it still did not give the Cambodians a sense of ownership of their own court. Hun Sen and Sok An would also highlight these concerns and successfully push for the ECCC to be established in Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital. While it could be argued that the ECCC was established near to the political power centre, it was situated, in fact, on the periphery of Phnom Penh’s metropolitan centre. To Dunleavy, The Hague offered the ideal location for the ECCC as it was the unofficial capital of international justice and a geographic centre which is easily accessible to the various actors involved in the ECCC. It is with this in mind that, while unsuccessful, the Group of Experts, Hans Corell and the US advocated a ‘positive’ central location.

In conclusion, the Dunleavy bureau-shaping model only partially supported my hypothesis. The most influential bureaucrats in these historic years were Hun Sen and Sok An, who ensured a judiciary Cambodian majority within the boundaries of Cambodia. While their primary proposals dominated the final ECCC Law, Dunleavy shows that the majority of these promoted negative values which would subsequently hinder the functioning of the ECCC. The US also exercised a large amount of influence by suggesting hybrid mechanisms, but these would also be deemed negative. On the other hand, while the UN provided a minimal level of influence, their proposals would have provided positive values, especially in the areas of staff functions and a central location. While lining up the analysis of the development of the ECCC against the Dunleavy bureau-shaping model, we can see only a partial indication of the bureaux success – the most significant analysis of the success of the ECCC can only be accomplished at the conclusion of the tribunal. In March 2014, only Case 001 with one defendant, Kaing Guek Eav, has been sentenced with Case 002, 003 and 004 still on-going (Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, 2014). Numerous factors still hinder the current functioning of the ECCC including judicial incompetency, allegations of corruption and financial aid. The defendants of senior Khmer Rouge officials are reaching old age and poor health seen, significantly, in the release of Alzheimer’s victim Ieng Thirith in September 2012 (British Broadcasting Corporation, 2012). The most significant factor in determining the success of the ECCC now, is time.

Akhavan, P. (2001). Beyond Impunity: Can International Criminal Justice Prevent Future Atrocities? The American Journal of International Law , 95 (1), 7-31.

Amnesty International . (2014, 01 01). Amnesty International: What We Do . Retrieved 01 10, 2014, from https://www.amnesty.org/en/human-rights-education/what-we-do

Annan, K., & Mousavizadeh, N. (2012). Interventions: A Life of War and Peace. London: Penguin Group.

Bangzao, Z. (2000, 11 07). China Won’t Pressure Cambodia on Khmer rouge trial. (A. Press, Interviewer) Associated Press.

Brady, B. (2009, 12 09). Cambodia’s first war crimes trial marred by flaws. Retrieved 12 12, 2013, from Los Angeles Times: http://articles.latimes.com/2009/dec/06/world/la-fg-cambodia-trial6-2009dec06

Brinkley, J. (2009). Cambodia’s curse: the modern history of a troubled land. New York: Public Affairs.

British Broadcasting Corporation. (2012, 09 16). Khmer Rouge ex-minister Ieng Thirith released. Retrieved 12 13, 2013, from British Broadcasting Corporation: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-19615534

Cairney, P. (2012). Understanding Public Policy . New York: Palgrave Macmillan .

Caswell, M. (2011). Using classification to convict the Khmer Rouge. Journal of Documentation , 162-184

Ciorciari, J. (2009). On trial: the Khmer Rouge accountability process. Phnom Penh: Documentation Center of Cambodia.

Corell, H. (2002, 02 08). Daily Press Briefing by the Office of the Spokesman for the Secretary-General. (F. Eckhard, Interviewer)

Corell, H. (2003, 03 11). Justice for the Killing Fields: Re-negotiating the Khmer Rouge Genocide Court for Cambodia . Retrieved 12 11, 2013, from Jurist Legal Intelligence : http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/forum/forumnew101.php

Dickerson, L. (2003). The Promice of Hybrid Courts. American Journal of International Law , 97 (2), 295-310.

Documentation Center of Cambodia. (1999, 05 14). Foreigners Killed at S-21. Retrieved 11 26, 2013, from Documentation Center of Cambodia: http://www.d.dccam.org/Archives/Documents/Confessions/Confessions_Killed_S_21.htm

Downs, A. (1964). Inside Bureaucracy. Chicago: Longman Higher Education.

Dunleavy, P. (1991). Democracy, bureaucracy and public choice: economic explanations in political science. New York: Harvester.

ECCC Budget and Finance Offices. (2013, 12 31). ECCC Financial Outlook. Retrieved 02 01, 2014, from Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia: http://www.eccc.gov.kh/sites/default/files/Financial%20Outlook%20-%2031%20Dec%202013%20Final%20version%20corrected.pdf

Ehrisman, K. M. (2013). The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia: Gauging the (In)Effectiveness of a Locally-Run Tribunal. Creighton International and Comparative Law Journal , 25-37.

Etcheson, C. (2005). After the killing fields: lessons from the Cambodian genocide . Westport: Praeger.

Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. (2014, 01 01). Case 001. Retrieved 01 12, 2014, from Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia: http://www.eccc.gov.kh/en/case/topic/1

Fawthrop, T., & Jarvis, H. (2004). Getting away with genocide? elusive justice and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal . London: Pluto Press.

Gottesman, E. (2003). Cambodia: After the Khmer Rouge. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Hammarberg, T. (1999, 04 22). Presentation to the UN Commission on Human Rights by Thomas Hammarberg, the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Human Rights in Cambodia. Retrieved 12 04, 2013, from http://cambodia.ohchr.org: http://cambodia.ohchr.org/WebDOCs/DocStatements/1999/Statement_22041999E.pdf

Hammarberg, T. (2001, 09 14). Special Insert: Efforts to establish a tribunal against KR leaders. Retrieved 12 11, 2013, from The Phnom Penh Post: http://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/special-insert-efforts-establish-tribunal-against-kr-leaders

Horsington, H. (2004). The Cambodian Khmer Rouge Tribunal: The Promice of a Hybrid Tribunal. Melbourne Journal of International Law , 5 (1), 1-21.

Howard J. De Nike, J. Q. (2011). Genocide in Cambodia: Documents from the Trial of Pol Pot and Ieng Sary. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Human Rights Watch Staff. (2000). World Report 2000: The Events of 1999. New York: PolitHuman Rights Watch .

Hyslop, L. (2011, 03 02). Cambodian court upholds convictions for murder of British mine-clearer. Retrieved 11 30, 2013, from The Telegraph : http://www.telegraph.co.uk/expat/expatnews/8356766/Cambodian-court-upholds-convictions-for-murder-of-British-mine-clearer.html

Jarvis, H. (2002). Trials and Tribulations: The Latest Twists in the Long Quest for Justice for the Cambodian Genocide. Critical Asian Studies , 34 (4), 607-624.

Kamm, H. (1998). Cambodia: report from a stricken land. New York: Arcade Publications.

Kiernan, B. (2005, 04 01). The Cambodian Genocide and Imperial Culture. Aztag Daily , pp. 20-21.

Kiernan, B. (1996). The Pol Pot regime: race, power, and genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lambourne, W. (2008). The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: Justice for Genocide in Cambodia? Law and Society Association Australia and New Zealand (LSAANZ) Conference (pp. 1-11). Sydney: Whither Human Rights.

Lint, W. d., Marmo, M., & Chazal , N. (2014). Criminal Justice in International Society. London: Routledge

MacGinty, R. (2011). International Peacebuilding and Local Resistance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mani, R. (2002). Beyond Retribution: Seeking Justice in the Shadows of War. Oxford: Polity.

Mertha, A. (2014). Brothers in Arms: Chinese Aid to the Khmer Rouge, 1975–1979. New York: Cornell University Press.

Nhem, B. (2013). The Khmer Rouge: Ideology, Militarism, and the Revolution that Consumed a Generation: Ideology, Militarism, and the Revolution That Consumed a Generation. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Niskanen, W. (1971). Bureaucracy and Representative Government. New York: Aldine-Atherton.

Niskanen, W. (1973). Bureaucracy: Servant or master. London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

Nouwen, S. M. (2006). ‘Hybrid Courts’: The hybrid category of a new type of international crimes courts. Utrecht Law Review , 2 (2), 190-214.

Panh, R. (Writer), & Panh, R. (Director). (2003). S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine [Motion Picture]. Cambodia, France: Institut national de l’audiovisuel.

Pike, A. (2002, 10 01). Diary Entry 1: Battambang The Judge. (PBS) Retrieved 12 14, 2013, from Frontline World: http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/cambodia/diary04.html

Quinn-Judge, S. (2006). The Third Indochina War: Conflict between China, Vietnam and Cambodia, 1972-79 . London: Routledge.

Ratner, S., Abrams, J., & Bischoff, J. (2009). Accountability for Human Rights Atrocities in International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Royal Government of Cambodia and the United Nations. (2004, 10 27). Law on the Establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers. Retrieved 12 15, 2013, from Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia: http://www.eccc.gov.kh/sites/default/files/legal-documents/KR_Law_as_amended_27_Oct_2004_Eng.pdf

Scheffer, D. (2008). The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. In C. Bassiouni, International Criminal Law (pp. 219-255). Chicago: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Shany, Y. (2014). Assessing the Effectiveness of International Courts. Oxford: Oxford

Stanton, G. H. (2003, 03 17). Seeking Justice in Cambodia. Retrieved 11 25, 2013, from Genocide Watch: http://www.genocidewatch.org/seekingjusticecambodia.html

Stensrud, E. E. (2009). New Dilemmas in Transitional Justice: Lessons from the Mixed Courts in Sierra Leone and Cambodia. Journal of Peace Research , 46 (1), 5-15.

Stephen Heder, B. D. (2001). Seven Candidate for Prosecution: Accountability for the Crimes of the Khmer Rouge. War Crimes Research Office, Washington College of Law, American University and Coalition for International Justice. War Crimes Research Office.

Stephen, N., Lallah, R., & Ratner, S. (1998, 02 18). Report of the Group of Experts for Cambodia established pursuant to General Assembly resolution 52/135. Retrieved 12 13, 2013, from Unakrt Online: http://www.unakrt-online.org/Docs/GA%20Documents/1999%20Experts%20Report.pdf

Subedi, S. P. (2011). The UN human rights mandate in Cambodia: the challenge of a country in transition and the experience of the special rapporteur for the country . The International Journal of Human Rights , 15 (2), 249-264.

The United Nations. (2012, 01 01). The Role of the Secretary-General. Retrieved 12 01, 2013, from The United Nations: http://www.un.org/sg/sg_role.shtml

The Washington Post. (2004, 08 09). Kerry’s ‘Christmas in Cambodia’. Retrieved 02 03, 2014, from The Washington Post: http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2004/aug/9/20040809-090612-9480r/

[1] ACRONYMS

| ECCC | Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia |

| CPP | Cambodian People’s Party |

| UN | United Nations |

| US | United States of America |

| FUNCIPEC | National United Front for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful, and Cooperative Cambodia |

| ICC | International Criminal Court |

| ICTR | International Criminal Tribunal of Rwanda |

| ICTY | International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia |

| ICTC | International Criminal Tribunal of Cambodia |