To speak of the Cold War in Asia is to position the history of Asia in the second half of the twentieth century in the complicated rivalry between the two superpowers – the United States and the Soviet Union. During that time, although an Asian country’s actions might have been driven by its own domestic concerns – nationalism, independence and nation building – the local systems were highly conditioned by the interests and decisions of the superpowers. In line with the post-revisionist stance,[i] this paper attempts to analyze the causes of the Cold War in Asia by examining the interactions of the two superpowers – their “intentional moves” toward each other, whether covert or overt – in four major wars and arrangements in postwar Asia. It argues that the Asian Cold War stemmed from a three-stage interplay of the two superpowers in the early regional conflicts. These three stages are cooperation, competition and confrontation. The earliest targeted moves from each side can be traced back to the stage of “competition;” however, each stage contributes to an initial development of the Asian Cold War: suspicions which arose from the failed “cooperation” between the two superpowers in the Chinese civil war evolved into cautious “competitions,” a stage signified by the U.S. change of occupation policies in Japan and the contests in the Korean War, and ultimately led to an open “confrontation” in the Vietnam War.

Mistrust Grown from Failed Cooperation: The Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War has been oftentimes regarded as the very start of the Cold War in Asia. While the two superpowers seemed to respectively support opposite national parties – with the U.S. assisting the Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Soviet Union supporting the Communist Party of China (CPC) – neither did they directly intervene during the civil war by sending forces of their own, nor did they clandestinely engage in a heated competition for spheres of influence on Chinese soil. Instead, their separate national interests in China primarily determined their actions in the civil war: the U.S. pursued its longstanding commercial interests, and also had a strategic interest in a strong China that would be able to fill a power vacuum caused by the absence of Japan in China in postwar period, while the Soviet Union tried to establish a buffer zone and secure the railway and ports in Manchuria and Xinjiang for its security and special interests. Their focus on individual interests could sufficiently explain the reasons why both advocated a coalition government of the KMT and CPC, why the Soviet Union maintained recognition of the ROC regime until 1949 – even when the Communist forces won victory in 1949 – so as to avoid provoking U.S. military intervention, and why the U.S. withdrew from the civil war to prevent the loss of “American prestige and recourses.”[ii]

Given the two superpowers’ lack of conspicuous conflicting interests and provocative moves toward each other, the argument of considering the Chinese civil war to be the origin of the Cold War in Asia thus does not hold water. That said, the joint engagement of the Chinese war still roused notable attention on each side, as seen in the heated U.S. debate over whether the government was too “soft on Communism” and a continuous political controversy of the question of “who lost China” lasting until late 1980s, thereby planting seeds of suspicions later in time.[iii]

A Cautious Competition –The Stage of “Probe and Test” for each other’s intentions –

The U.S. reversal of occupation policies in Japan and the Korean War

The skepticisms were spawned between the two superpowers after their first cooperation faltered in the Chinese civil war, and were heightened by the deadlock over trusteeship in the split Korean peninsula in mid-1947. Efforts made by the Allied Powers were continuously challenged by the arbitrary moves of the Soviets – a postwar plan of creating “a five-year provisional Korean government with a four-power trusteeship” and a later resolution of UN General Assembly that required a “peninsula-wide elections for a national assembly” with “an establishment of a supervisory body” were formally discarded as the Soviets established the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the North in September 1948 against the Allied-supported Republic of Korea. [iv]

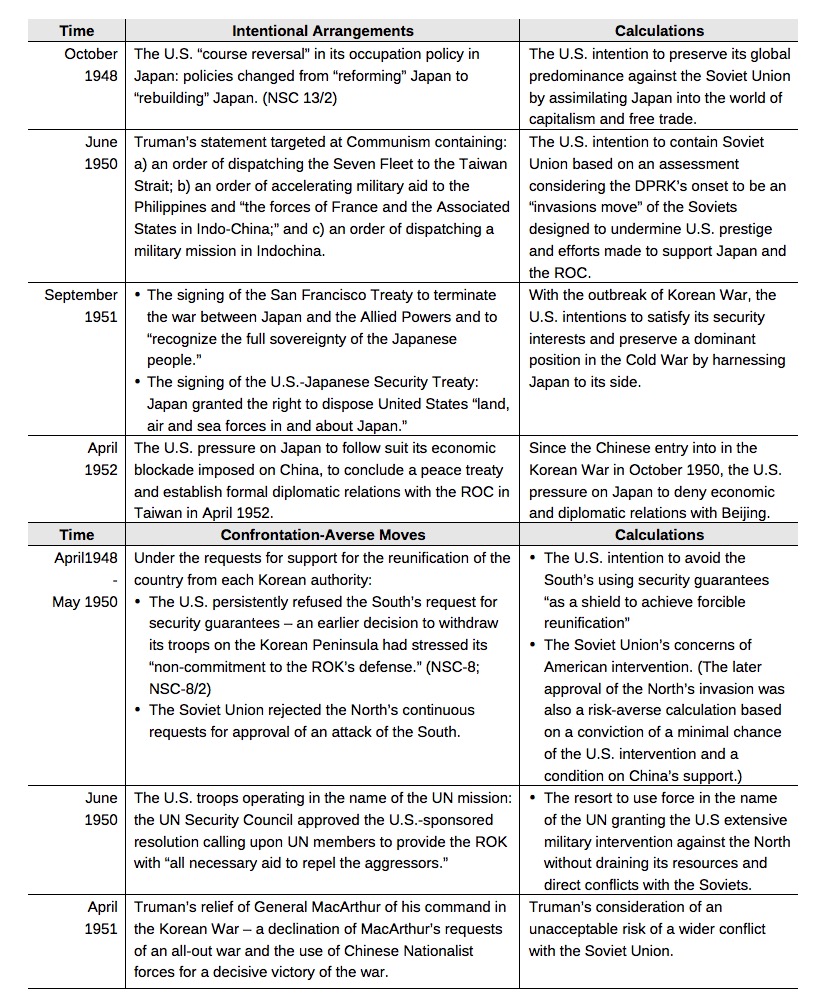

The growing mistrust between the U.S. and the Soviet Union had soon evolved into a palpable competition, albeit with caution, from the U.S. reversal of its occupation policy in Japan in October 1948 that culminated in the end of Japanese occupation in 1952, to the two superpowers’ “indirect” conflicts in the Korean War (1950-1953). (See Table 1.) Three characteristics can be noticed in this stage: 1) the suspicions from the two superpowers had been substantiated through careful actions targeted at each other; 2) the goals of each side’s cautious moves were to avoid confrontations and to serve as a litmus test for each other’s intentions; and 3) this stage of “probe and test” for each other’s intentions comprised two elements: intentional arrangements and confrontation-averse moves.

Table 1: Intentional Arrangements and Confrontation-Averse Moves of the Superpowers, 1948 – 1953

Resources: National Security Council, document NSC-13/2, 7 October 1948, in U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS), 1948, vol. 6 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1974), pp. 858-62; “Statement by the President,” 27 June 1950, in U.S. Department of State, FRUS, 1950, vol.7 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 196), pp.202-203; U.S. Department of State, United States Treaties and Other International Agreements 1952, vol.3, part 3 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1955), pp. 3329-40; 3161-91; National Security Council, NSC 8, 2 April 1948, in U.S. Department of State, FRUS, 1948, vol. 6, The Far East and Australasia (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1974), pp. 1164-65.

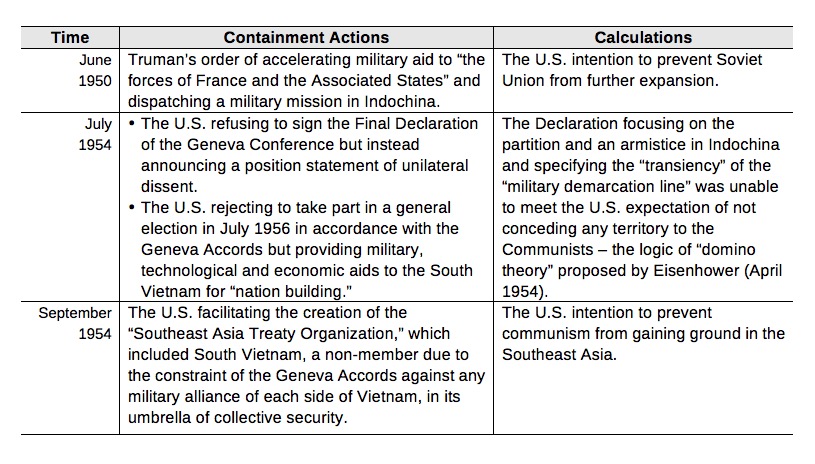

Confrontation – Provocative Moves without Reservation – The Vietnam War

For the U.S., the Cold War mindset – an antagonism towards Communism – consolidated itself in a plan to prevent Communist expansion in Indochina in February 1950. The imminent danger of the Soviet Union’s aggression was recognized in a National Security Council document, NSC-64, which clearly stated “the threat of communist aggression against Indochina” to be “only one phase of anticipated communist plans to seize all of Southeast Asia.”[v] This perceived threat from the Soviet Union was later confronted by a series of U.S. actions to contain the Soviet Union’s expansion in Indochina. (See Table 2.) The U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War thus proved to be an intentional move to overtly thwart Communist penetrations, driving the previous “probe and test” stage of competition into an open confrontation.

Table 2: The U.S. actions in preventing communist expansion in Indochina, 1950 – 1954

Resources: U.S. Department of State, FRUS, 1952-1954, vol. 16, The Geneva Conference (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1981), pp. 1540-42; Alice Lyman Miller and Richard Wich, Becoming Asia: Change and Continuity in Asian International Relations Since World War II (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2011), pp. 98-99.

For the Asian countries, the Cold War was not only the context in which they acted, but also the determining factor of their future development. For the two superpowers, the Asian theater was entangled with local nationalism and the interests of indigenous parties, thereby making it rather difficult to identify the other’s intentions and moves. The origins of the Asian Cold War should be sought not only in a superpower’s intentional move from a single event, but also in a sequence of early interactions of the superpowers in different settings. A pattern, as this paper’s observation of a three-stage development, could thus be found to adequately interpret the Cold War in Asia.

Notes and References

[i] Taking into account the regional situations and the complicated interlacing of events in the emergence of the Cold War, the post-revisionist view argues that the Cold War was instigated by “an interest-driven power struggle” between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Alice Miller, “The Origins of the Cold War: Alternative Interpretations” (class lecture, The International Relations of Asia Since World War II, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, February 11, 2014)

[ii] U.S. Department of State Policy Planning Staff, PPS39, 7 September 1948, in U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS), 1948, vol.8, 146-55 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1973).

[iii] Alice Lyman Miller and Richard Wich, Becoming Asia: Change and Continuity in Asian International Relations Since World War II (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2011), p.32.

[iv] Alice Lyman Miller and Richard Wich, Becoming Asia: Change and Continuity in Asian International Relations Since World War II (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2011), pp. 66-67

[v] National Security Council, document NSC-64, 27 February 1950, in U.S. Department of State, FRUS, 1948, vol. 6 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1974), pp. 744-47.

Bibliography

Miller, Alice Lyman and Wich, Richard. 2011. Becoming Asia: Change and Continuity in Asian International Relations Since World War II (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2011).

U.S. Department of State Policy Planning Staff, PPS39, 7 September 1948. U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS), 1948, vol.8, 146-55 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1973).

National Security Council, document NSC-64, 27 February 1950. U.S. Department of State, FRUS, 1948, vol. 6 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1974).

—

Written by: Emily S. Chen

Written at: Stanford University

Written for: Alice Miller

Date written: June 2014

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Importance of Western and Soviet Espionage in the Cold War

- Social Constructivism Vs. Neorealism in Analysing the Cold War

- Cuban Intelligence after the Cold War: A Case Study in Adaptation and Influence

- Were Fukuyama, Mearsheimer or Huntington Right about the Post-Cold War Era?

- Did Oleg Gordievsky’s Espionage Hasten the End of the Cold War?

- Revisiting Cold War Rhetoric: Implications of North Korean Strategic Culture