This week I am back in New York after an absence of fifteen years – in other words, my previous visit enabled me to see for myself the Twin Towers. A year later, and those iconic buildings were devastated by two hijacked planes, which were deliberately flown into the World Trade Centre. While it was not the first time the WTC was targeted by terrorists (in February 1993 a massive truck bomb was detonated and killed six people but failed to destroy the complex), the spectacular and horrific collapse of the buildings alongside an attack on the Pentagon and the downing of United 93 near Shanksville resulted in the death of nearly 3000 people. The late Neil Smith, a New York resident and critical geographer, provided an initial assessment of the events and its aftermath.

Given all the ensuing debate and even controversy about how to re-develop a devastated World Trade Center and the immediate surrounds, I was eager to see for myself the memorial and in particular the museum dedicated to 9/11 and its aftermath. Before you get to the museum, one passes the memorial pools. Set in the ‘footprint of the original Twin Towers’ (to quote the 9/11 memorial brochure which is translated into a number of languages but not Arabic), the winning design by Michael Arad envisaged two ‘abyss-like pools’ (see Martin Filler’s review 9/11 memorial) with cascading waterfalls. The names of the nearly 3000 victims are inscribed in bronze around the pools themselves. IR scholar Roland Bleiker offered his thoughts on the memorial and public art more generally post 9/11.

Given all the ensuing debate and even controversy about how to re-develop a devastated World Trade Center and the immediate surrounds, I was eager to see for myself the memorial and in particular the museum dedicated to 9/11 and its aftermath. Before you get to the museum, one passes the memorial pools. Set in the ‘footprint of the original Twin Towers’ (to quote the 9/11 memorial brochure which is translated into a number of languages but not Arabic), the winning design by Michael Arad envisaged two ‘abyss-like pools’ (see Martin Filler’s review 9/11 memorial) with cascading waterfalls. The names of the nearly 3000 victims are inscribed in bronze around the pools themselves. IR scholar Roland Bleiker offered his thoughts on the memorial and public art more generally post 9/11.

If you as I did, walk slowly around both pools, and read every single name, you will not be surprised to learn that it can take 20-30 minutes to do so. As I arrived early in the morning, I had only security personnel and memorial employees for company. Given my location, it was surprisingly quiet, and sobering to look up to the sky and see an occasional passing jet. The memorial was opened in 2011, and when the prevailing winds are too strong the waterfalls are turned off. So the noise, look and feel of the memorial pools changes inter alia with the time of day and daily weather patterns.

If you as I did, walk slowly around both pools, and read every single name, you will not be surprised to learn that it can take 20-30 minutes to do so. As I arrived early in the morning, I had only security personnel and memorial employees for company. Given my location, it was surprisingly quiet, and sobering to look up to the sky and see an occasional passing jet. The memorial was opened in 2011, and when the prevailing winds are too strong the waterfalls are turned off. So the noise, look and feel of the memorial pools changes inter alia with the time of day and daily weather patterns.

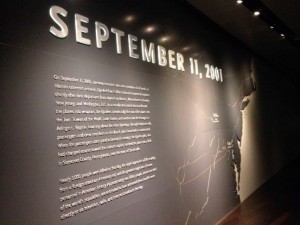

After my security screening, I entered the museum. As I intimated earlier, there is a strong presence of police officers and security staff at the memorial site and this does diminish once inside. If anything it seemed rather poignant going through an airport style security procedure – there were stories later that the 9/11 ring leader Mohammed Atta was testing US airport security prior to the September 11 2001 attacks. After passing the lengthy list of corporate sponsors written on a wall close to the screening area, you enter into the museum proper.

After my security screening, I entered the museum. As I intimated earlier, there is a strong presence of police officers and security staff at the memorial site and this does diminish once inside. If anything it seemed rather poignant going through an airport style security procedure – there were stories later that the 9/11 ring leader Mohammed Atta was testing US airport security prior to the September 11 2001 attacks. After passing the lengthy list of corporate sponsors written on a wall close to the screening area, you enter into the museum proper.

There are different ways of approaching the exhibition and exhibits – and in some parts of the exhibition you are allowed to photograph and others not (e.g. the historical exhibition). There are strict rules more generally in terms of how you are expected to behave both inside and outside the museum and prohibitions include, ‘Engaging in expressive activity that has the effect, intent or propensity to draw a crowd of on-lookers’.

For me the first part of the museum provides some context to that eventful day, with a large map depicting the plane movements, which is then interspersed with recordings of the relatives and friends of those who perished. As your scan the map, you can hear family members expressing shock, sadness, outrage and anger at what happened to those people who boarded four fuel laden planes on the Eastern seaboard all bound, or so they thought, for long flights to West Coast destinations.

One thing worth noting is that the February 1993 bomb attack on the Trade Center is enrolled in the accounting of the events and circumstances leading up to 11 September 2001 – this allows the museum to trace a longer geopolitical context, even if I do not recall reading/recording details about the long lasting legal battles involving the relatives of the dead and injured about who should shoulder responsibility for the 1993 bombing.

One thing worth noting is that the February 1993 bomb attack on the Trade Center is enrolled in the accounting of the events and circumstances leading up to 11 September 2001 – this allows the museum to trace a longer geopolitical context, even if I do not recall reading/recording details about the long lasting legal battles involving the relatives of the dead and injured about who should shoulder responsibility for the 1993 bombing.

Those legal battles regarding the 1993 bombing continued after 9/11 and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey were accused of failing to properly secure the underground parking facilities. Inadvertently, perhaps, it raises the question as to whether various US authorities, state and federal, should have anticipated and responded to the 1993 terrorist attack that followed. And in turn it reminds us that there were those, within the George W Bush administration, warning that there were opportunities to pre-empt such an attack in 2001.

All of which sits uneasily when you move on to the optimism (even hubris) that appeared to abound at the time when the World Trade Center complex was commissioned, funded, built and finally opened in the 1960s and 1970s. A detailed description of the imaginative and material labour involved in the making of the Twin Towers and other elements of the 16 acre Lower Manhattan site is offered up. Local geology, weather and proximity to the sea all made their presence felt during the construction process. Some of the foundational remains and the chipped and battered steps where some of the survivors clambered down are exhibited.

All of which sits uneasily when you move on to the optimism (even hubris) that appeared to abound at the time when the World Trade Center complex was commissioned, funded, built and finally opened in the 1960s and 1970s. A detailed description of the imaginative and material labour involved in the making of the Twin Towers and other elements of the 16 acre Lower Manhattan site is offered up. Local geology, weather and proximity to the sea all made their presence felt during the construction process. Some of the foundational remains and the chipped and battered steps where some of the survivors clambered down are exhibited.

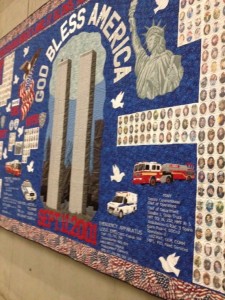

As one descends further into the lower reaches of the museum, the visitor is greeted with objects made in memorial to those who died – some of which appears quite bullish and confident in tone while others just seem terribly sad including the personal effects of the victims such as identity cards, bank notes, wallets, shoes and even a Sainsbury’s loyalty card from a British victim, Richard Dawson. He was one of 67 British citizens who died that day and I think I was drawn to him because I noticed by chance that we were born in the same year (1969). Dawson’s personal effects reside in a separate room, which allows you to find out more about all the victims through a touch screen archive. Each entry varies somewhat in terms of images, recollections and detail provided, however.

As one descends further into the lower reaches of the museum, the visitor is greeted with objects made in memorial to those who died – some of which appears quite bullish and confident in tone while others just seem terribly sad including the personal effects of the victims such as identity cards, bank notes, wallets, shoes and even a Sainsbury’s loyalty card from a British victim, Richard Dawson. He was one of 67 British citizens who died that day and I think I was drawn to him because I noticed by chance that we were born in the same year (1969). Dawson’s personal effects reside in a separate room, which allows you to find out more about all the victims through a touch screen archive. Each entry varies somewhat in terms of images, recollections and detail provided, however.

Although photography is prohibited in the historical exhibition, one should give credit for things that are tackled albeit discreetly. One example would be the ‘jumpers’ and the accusations made at the time and aftermath that much of the focus had been on those who had fought back on United 93, the families of the victims (e.g. the so-called ‘Jersey Girls’) and/or those attempted to secure the release of those trapped in the buildings (firefighters/police officers). Even on the 10th anniversary of 9/11, the ‘status’ of those who jumped was still subject to controversy about whether this group of men and women (possibly numbering some 200) were being marginalized (including visual images of tumbling bodies such as the ‘falling man’). In other parts of the museum, some recognition is given to dissent and resistance – from anti-war campaigners and conspiracy theorists who in their different ways questioned both the origins of the 9/11 attacks and the decision by the George W Bush administration to declare a war on terror in October 2011.

Although photography is prohibited in the historical exhibition, one should give credit for things that are tackled albeit discreetly. One example would be the ‘jumpers’ and the accusations made at the time and aftermath that much of the focus had been on those who had fought back on United 93, the families of the victims (e.g. the so-called ‘Jersey Girls’) and/or those attempted to secure the release of those trapped in the buildings (firefighters/police officers). Even on the 10th anniversary of 9/11, the ‘status’ of those who jumped was still subject to controversy about whether this group of men and women (possibly numbering some 200) were being marginalized (including visual images of tumbling bodies such as the ‘falling man’). In other parts of the museum, some recognition is given to dissent and resistance – from anti-war campaigners and conspiracy theorists who in their different ways questioned both the origins of the 9/11 attacks and the decision by the George W Bush administration to declare a war on terror in October 2011.

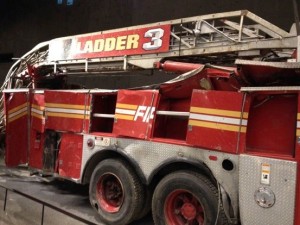

Other areas of the exhibition concentrate on surviving material objects; the remains of a fire truck, the tangled mess of one of the antennae that was once attached to the tower and abandoned bicycles and even pushchairs/strollers left by terrified parents/families enjoying a warm September’s day in Battery Park. Given the devastation of the immediate area, it is notable how many objects, big and small, are exhibited ranging from the pocket watch to a New York Fire Department fire axe. The archiving and storage of these objects plays a vital role in narrating and ‘feeling’ the immediate and longer–lasting impact of 9/11, especially when so much of the original site was pulverized by heat and subsequent building collapse.

Other areas of the exhibition concentrate on surviving material objects; the remains of a fire truck, the tangled mess of one of the antennae that was once attached to the tower and abandoned bicycles and even pushchairs/strollers left by terrified parents/families enjoying a warm September’s day in Battery Park. Given the devastation of the immediate area, it is notable how many objects, big and small, are exhibited ranging from the pocket watch to a New York Fire Department fire axe. The archiving and storage of these objects plays a vital role in narrating and ‘feeling’ the immediate and longer–lasting impact of 9/11, especially when so much of the original site was pulverized by heat and subsequent building collapse.

While IR scholars such as Michael Shapiro have in the past spoken about the World Trade Center and its reconstruction, I think there is more to be said about the embodied experiences of visiting the museum itself. The way in which the visitor is enrolled into the material cultures of 9/11 and its aftermath; the negotiation of the multi-scalar dimensions of the event itself (involving New Yorkers, US nationals and international citizenry), the memorialisation of the victims and their families (and the attention they are given within the museum); the prevailing geopolitical/historical contexts; and the affective atmospheres of nationalism and the war on terror itself –commemorating, commiserating and comforting.

While IR scholars such as Michael Shapiro have in the past spoken about the World Trade Center and its reconstruction, I think there is more to be said about the embodied experiences of visiting the museum itself. The way in which the visitor is enrolled into the material cultures of 9/11 and its aftermath; the negotiation of the multi-scalar dimensions of the event itself (involving New Yorkers, US nationals and international citizenry), the memorialisation of the victims and their families (and the attention they are given within the museum); the prevailing geopolitical/historical contexts; and the affective atmospheres of nationalism and the war on terror itself –commemorating, commiserating and comforting.

But there are people, moments and objects who and which offer up a different rendering of 9/11. As Sara Ahmed and Judith Butler remind us respectively, the war on terror ‘stuck’ to some bodies more than others, and some lives become more deserving of grief than others, and some objects attract more attention than others. Some things were lost forever. As Karen Till’s work on the places of memory in post-war Berlin shows, there is always work to be done in recording and recovering evidence of intentional forgetting and painful remembering.

As sailors and maritime lawyers know, there is a category of object called lagan – goods and wreckage that lies at the bottom of the seabed, which might be reclaimed in the future. What was and is submerged (but not necessarily lost) in favour of what emerged (let alone endured) remains very much a work in progress.

*All images by Klaus Dodds

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Incels: New Political Actors Emerging from the Manosphere?

- Opinion – Russia’s Bombing of Ukraine’s Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial

- Contexts and Questions Around the UK’s New Protect Duty

- Securitisation and Vernacular Discussions of Terrorism on Social Media

- Opinion – A New Balance in Sino-US Relations?

- The United Nations in Crisis: Geo-Political and Geo-Economic Challenges