In February of this year, three British schoolgirls from Bethnal Green, London, left the UK and flew out to Turkey, where they were last sighted preparing to cross over the border into Syria. It seems Shamima Begum, Amira Abase, both aged 15, and 16-year-old Kadiza Sultana had decided to join Islamic State. They were not the first British teenagers to do this, and as it rapidly became apparent, they were not the first school girls or young women from the UK to make this journey. In fact, one of their fellow classmates, 15-year-old Sharmeena Begum (no relation to Shamima), had made the very same trip just a few months before in December 2014.

However, something about this trio captured the media’s attention in a way that Sharmeena’s departure had not. Prior to the Bethnal Green girls leaving, it is estimated that between 50 and 60 girls and young women had left the UK in efforts to join Islamic State, yet none of these cases garnered quite the coverage sparked by these three girls from London. In looking at how the British media has portrayed these girls and their actions, we also need to ask why this story in particular captured the media’s imagination – and in doing so, consider how the media shapes our understanding of radicalisation and the route to extremism, as this in turn potentially shapes the efficacy of responses to such behaviours.

Politics and the Perception of the Bethnal Green School Girls

Shamima, Amira and Kadiza left little evidence regarding what led them to make their decision. There were no notes or messages explaining their motivations, at least none that have been made public. The one scrap of a clue the girls did leave behind was a shopping list, setting out who needed to buy what and dealing with the logistics of crossing the Turkish-Syrian border. Vikram Dodd, writing in The Guardian, repeats the details of the list, as if looking for answers in the fact that “an epilator is to be purchased at £50, as are two sets of underwear for two girls at £12.” While this list tells us that the girls were organised, that at least two people were involved in the planning (there were two sets of handwriting on the list) and, according to Tom Payne in The Daily Mail, the sum of money they decided they needed matches advice from Islamic State recruiters, it still can’t tell us what drove the girls to make such a dramatic decision.

With so little to go on, the media are left to construct their own version of events, filling in the silence left by the girls with a cacophony of possible explanations. As in other reports covering British women and girls joining Islamic State, the fact the girls were doing well at school and hence had a promising future ahead of them is the crux of the problem for the media. Why, the logic goes, would girls with so much available to them choose “a life where they will have to marry a fighter selected for them, never step foot outside without him, and become a household drone doing chores restricted to women”? (Sue Reid, Daily Mail).

The explanations put forward by the press are both predictable and political. To varying degrees, the school the girls attended, the police and security services, the government, and the girls’ families are all scrutinised and held accountable. While left-leaning journalism argues that a combination of cultural factors, normal teenaged behaviour and institutional failings led to the girls leaving for Syria, the conservative right turns to non-Western roots and habits, or the girls’ innate natures (for example, Zahra and Salma Halane are labelled “the terror twins” by the Mail Online), and finds fault with the families rather than the authorities.

Regardless of political affiliations, the mainstream media explanations for the girls’ actions repeat ideas, findings, and stereotypes explored in the rapidly swelling research library dedicated to the involvement of women and girls in extremist, militant or terrorist groups (see for example Bloom 2011; Victor 2004; Sjoberg & Gentry 2011; Gonzalez-Perez 2008). Romance or obsessive love; unhappy or traumatic domestic situation; brainwashing by charismatic man or – less often – woman; misguided ideas about women’s rights in society or in the group; being a social misfit; being vulnerable, naive and easily manipulated. These are the most common reasons research lists for women becoming involved in extremist groups – and all of these are touched on in some way by the British media’s portrayal of the Bethnal Green girls. And yet, what is absent here is the voice of the girls themselves. Without this, all else is speculative, and as Rajan has noted in her work on the media’s representation of women suicide bombers, women’s actions are “represented in ways that highlight them first and foremost as women, in line with common social ideologies about women . . . marked by the political ideologies of the nations/regions that produce them” (Rajan 2011, p.2). Thus, it is perhaps no surprise that the media finds the answers to the girls’ actions embedded in Western cultural stereotypes about female behaviour – stereotypes which match the political agenda of a particular press.

This is not to say that we should dismiss these ideas as possible explanation; rather, it is to highlight that the media portrayal of the girls’ decision is not necessarily offering us anything new empirically or objectively regarding their motives. However, there are some consistencies in the British media representation of the girls across the political spectrum, which immediately alert us to some of the fundamental assumptions that are being made in the way we understand extremism and radicalisation – which in turn underpin how we respond to such behaviour.

Failed Surveillance and the Fear of the Masses

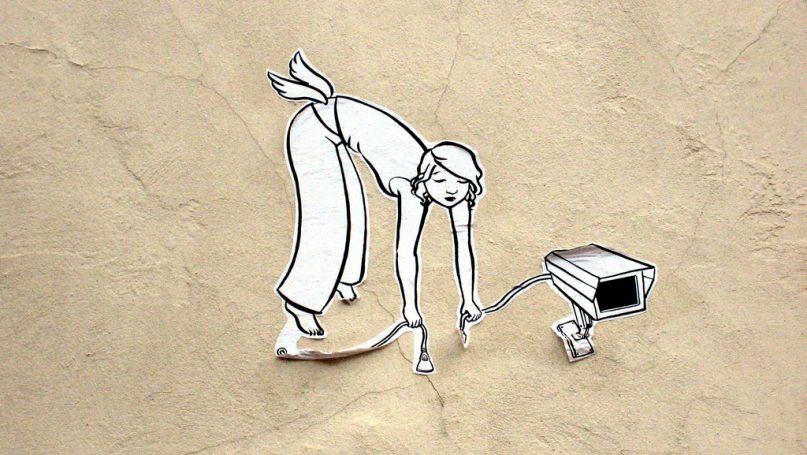

Across the British media coverage of the Bethnal Green girls, there are two prominent consistencies. One is the repeated use of two images in relation to this story, and the other is the importance accorded to the role of social media in every account. Indeed, these two aspects are potentially connected, although not in a way that is immediately apparent.

Two images were used again and again in the coverage of Shamima, Amira and Kadiza. Both were stills from surveillance camera footage at Gatwick Airport, as the girls were leaving the UK. The first shows the three girls walking through the airport together prior to check-in (see image here). The second is in fact three different shots, each of one of the girls passing through border control security. However, these separate images have been placed alongside one another in a way that, at a glance, suggests the girls passed through the gates simultaneously, looking for all the world like a girl band (see image here). The grainy quality of the images, coupled with the overhead perspective immediately alerts the viewer to the fact that these are surveillance images rather than photo-journalist shots and so on one level, these images demonstrate security cameras achieving their goal: they have recorded and traced the girls’ progress through Gatwick Airport. Yet the fact that these images are appearing in the media paradoxically also tells the viewer that there has been a failure in surveillance. If the supposed purpose of surveillance is to monitor in order to protect, be it through anticipating actions or intervention, these images are a poignant testimony to its failure: the CCTV cameras watched and recorded the girls’ passage through the airport, through security and out of the UK – but it did not prevent them going.

But at the same time, these images work to justify this failure to the viewer, particularly in comparison to other images representing female Islamist extremism. For example, the Mail Online reproduced images tweeted by another British woman known to have joined Islamic State, Aqsa Mahmood, showing herself and other British women in their new life, decked out in full niqab and burqa. In these photographs, the women’s commitment is visible, even if there is room for interpretation about to whom or what they are committed. By contrast, what we see in the image of the three friends strolling through Gatwick Airport is precisely just that – three teenaged girls, walking through an airport in the UK, looking like every other passenger passing beneath the cameras. In other words, these images show us that there is nothing to see; there are no outward signs of their intentions. These apparently radicalised girls passed as normal, and hence passed through security and out of the country under the watchful eye of security surveillance. As the media returns again and again to these images, the same question is being posed each time: if we can’t see radicalism even when we’re looking at it, how are we supposed to find it?

Arguably, this same anxiety emerges when it comes to discussions about the role social media played in the girls’ decision. In both the case of Shamima and Amira, as well as other teenagers and young adults who have gone to Syria, it is clear that social media such as Twitter, WhatsApp, Facebook and Ask.fm have all played a significant role in putting people in touch with members of Islamic State. Similarly, are all seen as part of what Sasha Havlicek describes in The Guardian as an “online communications strategy” on the part of Islamic State to target teenagers for radicalisation.

But these are forms of social media that almost everyone uses. In fact, it would be stranger if three teenage girls growing up in East London did not use them. Yet in the efforts by the media to explain the girls’ motivations, the internet and social media in particular become conduits that allowed “shadowy ISIS extremists” to target the girls’ iPhones and computers, while being ‘obsessed’ with your phone and being online all the time are sinister signs. However, as with the CCTV images, it is only hindsight that allows us to discern the exceptional from the average. When it emerged that Shamima had in fact contacted Aqsa Mahmood via Twitter, whose account was being monitored by counter-terrorist agencies in the UK, the Begum family lawyer demanded to know why “the family of that young girl do not have the customary knock on the front door” from the authorities. Again, surveillance had failed to do anything more than reveal, after the fact, that Shamima had asked to privately message Asqa on Twitter. Just as surveillance failed to detect the motives of the ordinary looking girls passing through the airport, so too did it fail to pick up the one tweet among the chatter of the internet that would result in an individual Twitter user taking radical action.

Anxiety and Mass Communication

Ultimately, this interrelated concern with the power of social media and the failure of surveillance is caught up with anxieties about mass culture: how do we spot the exceptional or the dangerous when it looks and operates like the rest of mass culture? If social media had this effect on these girls, what effect is it having on other users? How do we control or respond to the potential impact something as tenacious and pervasive as online media has on its unparalleled mass audience?

Although the terminology may be relatively new, these anxieties about communication with the masses are not. Work such as Laqueur and Alexander’s The Terrorism Reader (Laqueur & Alexander 1987) demonstrates that people have been concerned about the influence of messages communicated to mass audiences since the Ancient Greeks. Schlesinger et al. note that when the telegraph became widely used, people feared that the ability for news to travel rapidly would lead to “imitation effects”, with audiences replicating the newsworthy behaviour (Schlesinger et al. 1983, p.141). From the 1960s onwards, television has been given an increasingly central role in debates around terrorism and extremism, in a manner that assumes “an easily-persuaded, irrational mass audience, highly susceptible to televised propaganda” (Schlesinger et al. 1983, p.146), from which the critic is always exempt. Perhaps nothing exemplifies this fear quite as well as the decision by the British government to ban the broadcasting of Gerry Adam’s voice between 1988 and 1994, meaning that while images of the Sinn Féin leader could be aired, his words were voiced by actors – as if his voice alone was enough to terrorize or corrupt a vulnerable mass audience.

What we are seeing in the British media coverage of the Bethnal Green girls, then, are more traditional forms of broadcast and print media expressing the same anxieties about new media that were once expressed about themselves. But just watching television has not turned entire audiences into terrorists, so we need to question making too straightforward a connection between social media and radicalisation. As Brigitte Nacos’ insightful reading of fandom as a means for understanding the teenagers’ attraction to Islamic State suggests, the fact that so few people have decided to act on what they see online tells us that social media alone is not enough to lead to such radical shifts in behaviour. This is not to suggest that we should dismiss the idea that media forms impact the way audiences think and behave – indeed, as people like Schlesinger et al and Zulaika and Douglass argue (Schlesinger et al. 1983; Zulaika & Douglass 1996), the media representations of extremism and terrorism play a huge role in shaping the way not only the public, but politicians and researchers understand these actions. It is precisely because the mainstream media is crucial in how we construct the extremist that we need to be alert to trends and assumptions underpinning media representations. If we want to formulate an effective response to extremism and terrorism, we need to make sure we are responding to the specific factors that actually contribute to these choices, rather than to more generalised, persistent cultural anxieties that are caught up in the representation of the story. In other words, we need to respond to the facts, not to phantoms of our own making.

Responding to Radicalisation

So how does contextualising the representation of extremism and terrorism in this way help us to better understand the role different media play? First, it forces us to consider the specific influence different forms of media may have, rather than allowing us to rely on age-old stereotypes and assumptions about new media. For example, the language of ‘followers’, ‘following’ and ‘join us’ permeates social media in a way that is not present in other media forms, so perhaps this is one distinguishing feature of its impact. Second, it means we have to recognise that fears about mass influence lead to overinflated claims for the power of the media, which blindside us to some of the other very specific factors that contribute to a particular viewer or user responding to this content in a radical way. Ignoring the fact that the vast majority of viewers and users are not driven to make these choices risks leaving important contributing contexts unexamined.

Finally, being alert to the distinction between cultural fears and empirical fact is vital for protecting the very mass audience that generates these anxieties – protecting us from extremism, and from efforts designed to protect us. Rather than allowing us to straightforwardly accept that social media is now a space for non-lethal warfare, that needs to be patrolled and controlled by armies, censors, and surveillance teams, recognising that there is a specific set of factors that lead to radicalisation complicates the assumption that mass response is the answer to extremist behaviour.

Paying close attention to the specificities and nuances of a context that lead people to perceive and respond to things in particular ways is precisely the kind of subtlety the mainstream media struggles to represent. After all, while complexity makes good research papers, it does not make good headlines. Contextualising and analysing the media portrayals of these behaviours ensures we continue to add in this layer of complexity – and will ultimately help us produce more effective strategies for dealing with radicalisation.

References

Bloom, M., 2011. Bombshell: The Many Faces of Women Terrorists, London: Hurst & Company.

Dodd, Vikram, 2015. “London schoolgirls’ Syria checklist found in bedroom.” The Guardian, 9 March 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/09/london-schoolgirls-syria-journey-checklist-found-in-bedroom, accessed 23 May 2015.

Gonzalez-Perez, M., 2008. Women and Terrorism: Female Activity in Domestic and International Terror Groups, London: Routledge.

Greenhill, Sam, 2015. “Jihadi schoolgirl’s dad took her to hate preacher’s rally at 13.” The Daily Mail, 6 April 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3027035/Father-runaway-jihadi-schoolgirl-filmed-burning-flag-protest-admits-attending-says-took-daughter-demonstration-just-13.html, accessed 23 May 2015.

Halliday, Josh, 2015.”Syria-bound missing schoolgirl’s father urges her not to fall into clutches of Isis.” The Guardian, 22 February 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/22/uk-counter-terror-officials-criticised-syria-bound-london-schoolgirls, accessed 23 May 2015.

Iqbal, Nosheen, 2015. “The Syrian-bound schoolgirls aren’t jihadi devil-women, they’re vulnerable children.” The Guardian, 24 February 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/feb/24/syria-bound-schoolgirls-arent-jihadi-devil-women-theyre-vulnerable-children, accessed 23 May 2015.

Khaleeli, Homa, 2014. “The British women married to jihad.” The Guardian, 6 September 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/06/british-women-married-to-jihad-isis-syria, accessed 23 May 2015.

Laqueur, W. & Alexander, Y. eds., 1987. The Terrorism Reader : A Historical Anthology, New York: New American Library.

MacAskill, Ewan., 2015. “British army creates team of Facebook warriors.” The Guardian, 31 January 2015.

http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/jan/31/british-army-facebook-warriors-77th-brigade, accessed 23 May 2015.

Nacos, Brigitte L., 2015. “Young Western Women, Fandom, and ISIS.” E-International Relations, 5 May 2015. http://www.e-ir.info/2015/05/05/young-western-women-fandom-and-isis/, accessed 23 May 2015.

Narain, Jaya, Spillet, Richard & Akbar, Jay. “British ‘terror twins’, 17, who went to Syria tell family they are still in ISIS’s capital as hunt for on-the-run jihadi brides continues.” The Daily Mail, 13 May 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3079855/British-jihadi-brides-run-Iraq-EXECUTED-caught.html, accessed 23 May 2015.

Payne, Tom, 2015. “Socks, an epilator and mobile phones among items on runaway ISIS schoolgirls handwritten shopping list found in one their bedrooms after they disappeared.” The Daily Mail, 10 March 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2987485/Socks-epilator-mobile-phones-items-runaway-ISIS-schoolgirls-handwritten-shopping-list-one-bedrooms-disappeared.html, accessed 23 May 2015.

Rajan, V.G.J., 2011. Women Suicide Bombers: Narratives of Violence, London: Routledge.

Reid, Sue, 2015. “From joker to jihadi bride.” The Daily Mail, 3 March 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2978248/From-joker-jihadi-bride-exclusive-pictures-goofs-like-typical-London-schoolgirl-reveal-poisoned-mind-15-year-old-s-run-join-ISIS.html, accessed 23 May 2015.

Schlesinger, P., Murdock, G. & Elliott, P., 1983. Televising ‘Terrorism’: Political Violence in Popular Culture, London: Comedia.

Sinmaz, Emine, Reid, Sue and Marsden, Sam, 2015. “She loved Rihanna, clothes and make-up. The she fell under the spell of Islamists.” The Daily Mail, 13 March 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2994121/She-loved-Rihanna-clothes-make-fell-spell-Islamists-Jihadi-girl-s-father-tells-shadowy-ISIS-extremists-targeted-daughter-s-iPhone.html, accessed 23 May 2015.

Sjoberg, L. & Gentry, C.E. eds., 2011. Women, Gender, and Terrorism, Athens, GA.; London: University of Georgia Press.

Topping, Alexandra & Gani, Aisha, 2015. “School reaction to ‘Syria-bound’ schoolgirls: ‘it doesn’t make sense.'” The Guardian, 23 February 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/23/schools-reaction-syria-bound-schoolgirls-amira-abase-shamina-begum-kadiza-sultana, accessed 23 May 2015.

Verkaik, Robert, 2015. “Revealed – hundreds of desperate British women have proposed marriage to Isis extremists online after EIGHT schoolgirls followed the ‘jihadi bride trail.'” Mail Online, 23 February 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2965495/Revealed-EIGHT-British-schoolgirls-left-follow-jihadi-bride-trail-hundreds-desperate-women-proposed-marriage-Isis-extremists-online-thanks-jihadmatchmaker.html, accessed 23 May 2015.

Victor, B., 2004. Army of Roses: Inside the World of Palestinian Women Suicide Bombers, London: Robinson.

Zulaika, J. & Douglass, W.A., 1996. Terror and Taboo: The Follies, Fables, and Faces of Terrorism, London; New York: Routledge.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Considering the Whole Ecosystem in Regulating Terrorist Content and Hate Online

- Securitisation and Vernacular Discussions of Terrorism on Social Media

- Toxic Citizenship, Everyday Extremism and Social Media Governance

- Islamic State Men and Women Must be Treated the Same

- Post-Truth and Far-Right Politics on Social Media

- Critical Security Studies Needs to Better Consider the Intricacies of Social Media