To find out more about E-IR essay awards, click here.

—

Democratization, the State, and the National Interest: Explaining South Korean Policy Toward the United States, 1987-2014

Six decades following the official establishment of their security alliance, the Republic of Korea (ROK) and the United States are enjoying a new period of robust cooperation and mutual good feelings in their bilateral relationship. Despite lingering elements of actual and potential disagreement in their policy outlooks, Seoul has been eager to remain a valuable and contributing member in the US-led regional and global architecture, and Washington has reaffirmed its commitment to defending the ROK and supporting its various foreign policy efforts, particularly regarding the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Traditional cooperative activities between the two allies, such as combined military exercises and regular meetings between both working and high-level officials, are continuing in a systematic manner and gradually expanding in scale and scope. In view of such trends, a report published in 2014 by the US Congressional Research Service states that in recent years bilateral relations “arguably have been at their best state since the formation of the US-ROK alliance in 1953.”[i]

The optimism that currently prevails in the ROK-US relationship is puzzling. During much of the previous decade, mainstream analysts observed an atmosphere of considerable tension and unease between South Korea and the United States, with some even going so far as to predicting that their alliance would not survive. Various factors contributed to this weakening of bilateral ties, but none were as fundamental as the perceived and actual decline of South Korea’s traditional commitment to maintaining and strengthening the alliance relationship that took place after its democratic transition in the mid-1980s. Observing an upsurge of anti-American sentiment within the South Korean public and Seoul’s outspoken intransigence toward Washington in several important policy agendas, the New York Times bluntly stated in 2003 that while “for half a century the United States [had] had no more stalwart ally in Asia than South Korea,” it had since then turned into “one of the Bush administration’s biggest foreign policy problems.”[ii]

The trajectory of South Korean foreign policy during the period that roughly comprises the last two decades thus yields compelling empirical questions. Why did Seoul’s commitment to the ROK-US alliance wane in the aftermath of democratization? More important, what explains its subsequent revitalization, or more precisely, return to the traditional equilibrium? Answering such questions in a systematic manner should be a task of exceptional value for students of East Asia’s political development and interstate relations, especially now that the Obama administration’s policy toward this key region places a renewed emphasis on strengthening bilateral engagements.[iii]

This essay aims to provide a structured understanding of South Korea’s contemporary policy toward the United States by examining it from a “state-centric” or “statist” perspective. Statism, following Stephen D. Krasner’s seminal study, is the image of the state as an autonomous actor whose main function is to pursue goals that are associated with the general interest of the society as a whole, as opposed to the particular interests of any of its constituent individuals or groups. These goals can be properly termed the public or national interest. In short, unlike previous studies on the subject which largely neglect the independent role of the state, my analysis of South Korean foreign policy is grounded upon “an intellectual vision that sees the state autonomously formulating goals that it then attempts to implement against resistance from international and domestic actors.”[iv]

My central argument is that the resilience of South Korea’s commitment to the ROK-US alliance is explained in large part by the unique capabilities and preferences of the ROK’s central decision-makers—that is, its state.[v] Although South Korea’s national interests have been inextricably tied to the ROK-US alliance throughout much of its modern history, the process of democratization that began in the mid-1980s temporarily disrupted its historical commitment to maintaining strong bilateral ties with Washington by increasing the influence of “progressive” elites and special interest groups in its political environment.[vi] However, the ROK-US alliance has survived and even flourished due to the decisive influence that Seoul’s central decision-makers have retained in the process of formulating foreign policy, coupled with the “rationalizing effect” that the North Korean threat has had on their strategic outlooks. A close examination of major policies implemented by South Korea’s central decision-makers shows that their preferences regarding the ROK-US alliance have remained remarkably consistent in the years following democratization, and that they have worked with extraordinary unanimity and vigor to ensure a substantial level of alliance commitment despite resistance from newly empowered domestic forces. In short, although dynamics driven by domestic societal interests and aspirations did have significant impact on the ROK’s foreign policy, they were ultimately overridden by the general strategic concerns of central decision-makers who remained highly sensitive to the requirements of security competition on the Korean peninsula.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, I briefly examine previous studies on South Korea’s post-democratization policy behavior toward the United States. In doing so, I suggest that the societal interest group-centered approach to politics that underlies much of the existing research at best provides an incomplete analytical framework in attempting to make sense of the overall direction of South Korea’s foreign policy during the period in question. Next, I outline my alternative statist framework, which primarily draws on the work of Krasner but also incorporates the insights of other important theoretical literature as well. This framework is then used to explain the trajectory of South Korean policy toward the United States, focusing on the developments that have taken place in the wake of its democratic transition in the mid-1980s. I finish with a conclusion that highlights the main theoretical and policy implications of this analysis.

The Previous Literature

Numerous analysts in the past decade observed a decline in South Korea’s traditional commitment to its alliance with the United States, and explained this as a result of the changes that had occurred in the values, sentiments, and interests harbored by influential segments of the South Korean society. They pointed to South Korea’s democratic transition as the critical development that had provided the backdrop for such changes. Byung-Kook Kim, for example, argued that the democratic reforms had enabled the political rise of the so-called “386 Generation,” whose members had led the struggle against South Korea’s former authoritarian regimes. The historical experience of the new generation had caused many of its members to harbor critical views of the United States and downplay its role in South Korea’s national security. In a democratizing political environment, these elites also found that flaunting their nationalist vision in foreign affairs can be useful in bolstering their own legitimacy and political standing vis-à-vis more moderate leaders.[vii] The rise of this “progressive” age group to the center of South Korean politics in the wake of democratic transition thus opened the door for previously latent anti-American sentiments to make a strong impact on Seoul’s behavior toward the United States.[viii]

Some writers also highlighted the role of special interest groups that, for ideological or material reasons, harbored resentment toward the United States and the ROK’s traditional security relationship with that country. Over the years preceding political democratization, South Korea had grown into an open and prosperous country that was remarkably well-integrated into the global economy. When a powerful wave of new information technologies (IT) swept through the globe during the last decade of the twentieth century, the South Koreans quickly became some of the world’s most proficient users of these technologies. With more than 30 million citizens among a population of 45 million having daily access to the internet and the number of mobile phone and personal computer users among the world’s highest by the first decade of the 21st century, social actors in South Korea came to attain an unprecedented capacity for political action. The so-called “IT revolution” enabled what Hyug-Baeg Im has termed “neo-nomadic” political participation, in which citizens take advantage of cutting-edge tools of communication and networking to engage in highly mobile, spontaneous, and expeditious forms of collective action to influence the process of political agenda-setting and decision-making.[ix] Coinciding with the progress of South Korea’s institutional opening, the immediate effects of this profound social change was that previously marginalized societal actors—such as citizens’ groups, non-governmental organizations, and non-mainstream media—were elevated to positions of newfound political significance, along with the anti-American or anti-alliance values many of them espoused.[x]

Compared to the downward turn in the ROK-US relationship that followed South Korea’s democratization, the perceived and actual revitalization of the alliance that has taken place in recent years has been relatively understudied. However, it is clear that most existing observations on the renewed strength of bilateral ties tend to assume that the resurgence of conservative societal forces has constituted the main countervailing factor against the disruptive impact of democratization. The most simplistic application of this pluralist logic is found in the widespread notion that the dominance of pro-US forces within South Korean politics, epitomized by the election of the conservative Lee Myung-bak to the presidency in 2008 and that of his successor Park Geun-hye in 2013, by itself explains the current health of the alliance. This is the standard view that is often alluded to in media reports and policy-oriented overviews on South Korean politics.[xi] Scholarly treatments have also seen the alliance’s revitalization as a phenomenon led by alliance-friendly societal interests. For instance, in his conclusion of the same study cited above, Byung-Kook Kim took note of “the beginning of the conservative societal forces’ drive to organize into a counterbloc and to bring the issue of military security to the fore,” implying that the conservative elements of society that harbored more traditional threat perceptions might potentially be able to revitalize the ROK-US alliance, provided that they succeeded in seizing the upper hand over their progressive rivals.[xii] Dong Sun Lee also cited the lingering power of the old conservative elites in South Korea’s government and media as a critical factor that moderated the destabilization of the alliance, although he nonetheless doubted that their political clout would be able to prevent the alliance’s downfall altogether.[xiii]

The reasoning contained in much of the literature reviewed above tacitly assumes that the character of political outcomes is ultimately decided by the capabilities and preferences of societal actors, and therefore reflects the influence of a well-established tradition of social scientific research known as pluralism.[xiv] Extended to the study of international politics, the pluralist approach challenges the traditional state-centric view of realism, suggesting that

states (or other political institutions) represent some subset of domestic society…representative institutions and practices constitute the critical ‘transmission belt’ by which the preferences and social power of individuals and groups are translated into state policy.[xv]

As a basic rule, the pluralist paradigm does not place a meaningful distinction between public and private actors. All state institutions are seen as highly constrained by societal pressures, and the officials who work through them, at best, another interest group among many.[xvi] The practical implications of this perspective are twofold. On the one hand, policymakers who seek to preserve the solidarity of the ROK-US alliance in democratic South Korea should, first and foremost, look for ways to promote the strength of alliance-friendly societal forces within its political environment. On the other hand, one should nevertheless expect bilateral ties to be unstable in the long run, prone to decline according to the ever-changing balance of political influence among different societal groups.

Studies that focus on the interests and aspirations of societal groups have contributed immensely to our understanding of Seoul’s foreign policy behavior in the wake of democratic transition, and indeed form the groundwork of a large portion of the analysis that will be laid out in this article.[xvii] However, as will become evident throughout the course of my discussion, any analysis that places exclusive weight on the competitive political pressures exerted by societal groups provides at best a partial explanation of the trajectory of South Korea’s contemporary policy toward the United States, and by extension, the broader consequences of East Asia’s political transitions. From a theoretical perspective, two inherent limitations of a pluralist approach immediately stand out. In the first place, an interest-group centered theory has difficulty explaining instances in which an essential continuity is observed in a state’s long-term policy behavior in the midst of large-scale socio-political change. Finding that the aims of official policy-makers tend to basically converge toward a certain direction or priority despite significant shifts in prevailing societal sentiments or ideals would, at the least, point to the need to identify a new explanatory variable that an interest-group oriented perspective fails to capture. Second, pluralist analyses have limited use in making sense of decisions taken by political leaders that directly contradict the aims and activities of major domestic groups. It is especially unclear how the “bottom-up” reasoning of pluralism can accommodate instances, such as those covered in my case study, where central decision-makers implement major policies that even provoke intense conflict with their own societal base of support.

A Statist Perspective

The fundamental shortcoming of the previous literature lies in the fact that their underlying paradigm of government behavior fails to account for the unique role of central decision-makers in the formulation of foreign policy, opting instead to treat them as mere interpreters or reactors within an ever-changing constellation of societal pressures. By contrast, the analytical framework employed in this essay sees the state as an autonomous actor that pursues objectives distinct from those pursued by any particular societal group. This statist or state-centric view was powerfully expounded by Krasner in his 1978 study, Defending the National Interest. In this work, Krasner articulated an image of foreign policy as a product of the state’s effort to pursue goals associated with the general material or ideological interests of society—the national interest—against resistance from both foreign and domestic actors. In the discussion that follows, I will adapt Krasner’s arguments to elaborate a statist framework that can illuminate the course of South Korea’s post-democratization foreign policy.

The Concept of the State

For Krasner’s statist image of foreign policy, the concept of the state is not coterminous with government but with the components of government that are characterized by a “high degree of insulation from specific societal pressures and a set of formal and informal obligations that charge them with furthering the nation’s general interests.”[xviii] The recognition that these bodies can act in a coherent and strategic manner to implement their preferences in foreign policy is a central premise of statism. This is not an unreasonable assumption. Note J.P. Nettl’s eloquent observation in his influential study:

The fact is that this international function is an invariant; countries with a low degree of “stateness” in the intrasocietal field have to make special differentiated provisions accordingly (like the special status of the British Foreign Office vis-à-vis other governmental bureaucratic organizations, the awkward duality and conflict between interstate and interparty relations among Communist states, and finally the very special status of foreign affairs in federal societies like the United States and Switzerland, where they are one of the primary raisons d’être for the claim for stateness on the part of the federal government)…Whatever reasons there may be for talking about the British government rather than the British state do not affect Britain as a state (or national actor) viewed from the point of view of the international arena (or system).[xix]

As Nettl points out, virtually all advanced countries have adopted some form of institutional arrangement to endow certain core bureaus and officials in their governments with a significant amount of concentrated and independent authority in foreign affairs, despite the fact that in many of them, the dominant political ideology emphasizes the decentralization of power. According to Krasner, such “central decision-makers” or “central state actors” in the United States include the President (i.e. the White House) and the Secretary of State. The ROK’s central state actors can similarly be said to comprise the Presidency (i.e. the Blue House) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with the possible addition of the Ministry of National Defense.[xx] The success of these institutions, and the political legacies of the individuals that lead them, are not evaluated in terms of their service to any particular societal interest but by their contribution to the overall well-being of the society. Their insulation from particularistic societal pressures and the broad-based character of their mandate endow the President and other core executive officials with a special capability and incentive to guide the policymaking process in the direction of what they perceive as the nation’s general interests.

The distinctiveness of the foreign policy preferences of central state actors gives substance to the concept of the “national interest.” Following Krasner, the national interest can be inductively defined as “an empirically validated set of transitively ordered objectives that [does] not disproportionately benefit any particular group in a society.”[xxi] This is an intriguing definition, and it is useful to consider its two dimensions separately. In the first place, for any collection of policy objectives to be dubbed the national interest, their benefits or costs must not consistently fall on a specific segment of society, and in this way, they must be related to the society’s “general” interests.[xxii] Again, it is not unreasonable to think about certain political objectives in these terms. Although writers who espouse a pluralist image of politics typically reject the notion of such general interests altogether,[xxiii] the conceptual differentiation between the public or general welfare and the particular needs of private groups has always been an integral part of Western political thought, and in particular, the classical liberal tradition implicit in modern governmental practices and institutions. Friedrich A. Hayek recognized that the task of securing the general interests of society was the single most compelling justification for the coercive powers of government, arguing that the central concern of such acts was not in directly satisfying some agglomeration of private desires but in “creating conditions likely to improve the chances of all in the pursuit of their aims.”[xxiv] A practical application of this distinction can be found in the consistent emphasis Hayek placed throughout his intellectual career on the need for a formal and equally applicable system of rules—commonly known as the “Rule of Law”—in the sustainment of individual freedom and societal progress, and also in his efforts to expose the folly of domestic political schemes based on the notion of “social” or distributive justice. The former plausibly increases opportunities for any randomly chosen individual to use his own knowledge to attain his freely chosen ends—if not immediately, then almost certainly “‘on the whole’ and in the long run.” The latter, by contrast, he saw as little more than hollow rationalizations for the arbitrary application of governmental power to satisfy the parochial claims of special interest groups.[xxv]

The qualitative difference between policies that are related to the general interests of society and those that merely satisfy the demands of special interest groups is conducive to Krasner’s assertion that policies that further the national interest can only be defined and pursued “in terms of the preferences of central decision-makers, that is, the state.”[xxvi] As F.R. Cristi notes, for all its emphasis on limiting government power even the liberal tradition à la Hayek “distinguishes sharply between civil society and the state…the negative tasks ascribed to the state are determined and sustained by the action of the state itself.” On the basis of this distinction, Hayek himself accepted that “whenever the normal working of civil society becomes in any way imperiled, so that its spontaneous order must be converted into an organization…the power to declare an emergency belongs to the state.”[xxvii] Precisely due to the pluralistic nature of modern society, only the state has the overarching authority and resources necessary to identify and enforce decisions that effectively address the general condition of the whole community. Hence, for the purpose of empirical inquiry, it is useful to think of the national interest as “the goals that are sought by the state.”[xxviii]

Second, the notion of a national interest is only tenable if the policy goals associated with it are pursued for an extended period of time with a priority ranking that remains largely constant. As Krasner notes, this allows us to isolate the preferences of central state actors from those of societal interest groups: “For any single decision it is possible to impute a rank-order of objectives, but if this changes from day to day or even from year to year, it would be misleading to use the term ‘national interest.’ One would better look to bureaucratic preferences or societal pressures to understand the actions taken by central decision-makers.”[xxix] Put differently, the notion that the state can act in a coherent manner to promote a national interest that is distinct from some combination of private interests is viable only if the state’s commitment to a certain set of policy goals withstands the test of time, which may encompass leadership turnovers, regime transitions, and large-scale social transformations. In turn, the resilience of general foreign policy objectives amidst shifting societal coalitions and attitudes can only be fully understood with reference to the national interest.

Pursuing the National Interest in the Wake of Democratization

An analytical framework which holds that the state can act in a unified manner to pursue goals associated with the national interest does not deny that the activities of societal interest groups can influence foreign policy outcomes. However, rather than focusing on how competing societal groups use political institutions to assert their needs and desires in public policy, a statist analysis highlights the state’s ability to control the private groups within society in order to secure its independently determined goals.[xxx] Whether the particular societal preferences that are strengthened through the process of democratic opening will prevail over the national interest ultimately hinges on how much power or influence the state retains vis-à-vis societal interest groups in the realm of foreign policy. In more formal terms, the strength and preferences of the state still have causal primacy in determining the trajectory of the nation’s foreign policy in the wake of democratization. Provided that the state has managed to retain its core institutions and functions during the process of regime transition, a combination of three factors endow central state actors with a considerable ability to cope with the impediments generated by the rise of societal forces. The first two, identified by Krasner, derive from the capabilities and institutional mechanisms that are available to state actors. The third underscores the impact of the international system.

In the first place, a well-established state can exercise political leadership to defend the national interest from the more egregious consequences of interest group penetration. Owing to their political clout and the sheer centrality of the issues that they handle, central decision-makers are endowed with a capability for persuasion and manipulation that is not available to private individuals and groups. They can appeal to values that enjoy widespread concurrence in society and clearly define specific foreign policy agendas in terms of general societal concerns (e.g. national security). This allows the state to shape the attitudes held by influential political actors and broad segments of the civil society and override the activities of those who remain recalcitrant to a degree that virtually no private actor can emulate.[xxxi] It is especially important to note that, should they fail at the task of extracting societal support, central decision-makers still possess considerable authority and resources within the structure of government that allow them to move forward with policies that they deem critical to the national interest. The President, in particular, is especially capable of imposing his will on policy outcomes via “his selection of bureau chiefs, determination of ‘action-channels,’ and statutory powers.”[xxxii]

Second, central state actors can gain an upper-hand over societal interest groups in the realm of foreign policy by controlling the “decision-making arena” in which policy issues are settled. Decisions on particular policy questions can vary significantly, depending on whether they are taken in arenas that are highly sensitive to pressure from narrow interest groups or in those that are relatively independent from such pressure.[xxxiii] Recognizing this, when the President or other central state actors perceive a core national interest in a certain policy issue, they try to keep the relevant decision-making process within political arenas that are relatively insulated from societal pressures. In this effort, they are significantly aided by the distinctiveness of international politics as a realm of policy. As Krasner argues, despite the “claim that there is little difference between domestic and international politics, the fact remains that there is no domestic equivalent to war, and there are few analogs to the kinds of solidary appeals that political leaders can make when the state acts in the international system.”[xxxiv] By redefining policy issues in terms of broad political goals such as war prevention or national competitiveness, central state actors can keep the locus of decision within policy-making arenas in which a relatively high degree of autonomy, and perhaps even secrecy, is ensured.

Finally, assertive political leadership and active attempts to shape favorable decision-making conditions will most likely take place in a setting of a highly constraining international environment. This is what might be termed the “rationalizing effect” of international systemic pressures on the behavior of a state. From a descriptive standpoint, it is quite accurate to say that key officials, as individuals, enter their positions with various foreign policy visions, not all of which are conducive to the promotion of the national interest. However, while these visions need not disappear immediately or completely upon taking office, the incentives and constraints generated by competition in an anarchic international system causes the foreign policy outlook of rulers in all but the most secure and confident of states to embrace the imperatives of the national interest. In particular, a potentially dangerous adversary tends to quickly make its presence felt in the minds of central decision-makers. Once this happens, statesmen become highly sensitive to the varying effects of policy choices on the nation’s overall capability to deal with this threat. Policy stances that are revealed to have been self-defeating or gratuitous will be modified, and determined efforts will be made to compensate for the setbacks that have already been incurred.[xxxv]

In sum, the statist framework provides a way of thinking about the foreign policy decision-making process and its outcomes that can overcome the limitations of the previous pluralist approaches while still accounting for the impact of domestic societal actors. On the one hand, a state-centric perspective recognizes that democratization can undermine the pursuit of the national interest by strengthening the influence of particular societal groups in the foreign policy decision-making process. On the other hand, the state does not idly stand by. Especially when stimulated by the pressures of the international system, it actively employs a formidable array of resources and maneuvers in order to defend the national interest against the degenerating impact of particularistic societal interests. In this framework, then,

the state is a genuine entity with a life of its own that acts as the true representative of national interests…Society might be powerful enough to sometimes trump the state, but the latter is generally not merely the reflection of aggregation of the former’s interests, as is the case with the more ‘pluralist’ theory of the state adopted by liberals.[xxxvi]

Finding that the foreign policy of a particular country is primarily driven by the power and preferences of its central decision-makers, who in turn are provided with incentives for “rationality” in view of the state’s objective standing within the international system, would point to the usefulness of explicitly state-centric approaches to the study of international relations, such as those set forth by “neorealist” or “neoclassical realist” scholars. My main goal in the following case study, however, is not to lend support to any specific research program or claim within the realist tradition but simply to show that its statist corollary is an adequate starting point for illuminating the sources of foreign policy. The case of South Korea’s policy toward the United States in the aftermath of its democratization is well-suited for the purpose of evaluating the plausibility of the statist framework, because it exhibits “high values” of elements highlighted by both pluralism and statism, such as a political environment that has become highly sensitive to the demands of newly empowered societal actors and exceptionally well-developed state institutions. In other words, it represents a case in which opposing predictions made by competing theoretical frameworks are usefully pitted against each other.[xxxvii] It is to this case that we now turn.

The Case: Democratization and ROK Policy Toward the United States

The explanatory power of a state-centric image of foreign policy is revealed by an examination of major South Korean policy decisions in the aftermath of democratization. While there have been significant changes in the constraints and challenges presented by the domestic political environment in terms of Seoul’s stance towards the ROK-US alliance, maintaining and strengthening bilateral ties with the United States has always remained the first order of the ROK’s foreign policy. On the surface, the process of democratization that began in the mid-1980s did weaken Seoul’s traditional commitment to the alliance, as the state’s historical supremacy in the foreign policy realm was challenged by the rise of powerful domestic interest groups. Armed with compelling ideological agendas and mistaken strategic beliefs, these groups had considerable success in undermining the centrality of the ROK-US alliance in South Korean foreign policy in favor of promoting political autonomy and inter-Korean solidarity. However, such disruptive tendencies were countervailed by the political leadership exercised by central decision-makers, who recognized the value of the ROK-US alliance in view of South Korea’s immediate and long-term national interest.

Nationalism, Special Interests, and Alliance Troubles

At a first glance, the changes that took place in Seoul’s behavior toward the United States after democratic transition in the mid-1980s seem to lend credence to the explanatory potential of pluralist approaches. Despite having been brought about partly as a result of US pressure, democratization in South Korea presented the ROK-US security relationship with what was perhaps the most severe trial it had ever experienced.[xxxviii] After the Chun Doo-hwan administration officially legalized dissident political activities that were suppressed throughout the authoritarian period, progressive elites who had spearheaded the struggle for democracy gained new influence within the South Korean government. In the presidential election of 1992, former dissident leader Kim Young Sam became the first civilian president to be elected since 1960, albeit as a candidate of the ruling Democratic Liberal Party. The decisive power shift came in 1997, when Kim Dae-jung—the internationally renowned leader of South Korea’s democratic movement—won the presidency. The control of the executive branch by former opposition leaders was then extended and reaffirmed in 2002 with the election of Roh Moo-hyun. In addition to this series of achievements in presidential elections, the new elites steadily increased their influence in the legislature. In the 12th National Assembly election of 1985, political parties commonly designated as “progressive” collectively won 24.2 percent of the seats. By the 17th National Assembly election of 2004, this proportion had risen to a majority of 57.1 percent.[xxxix]

Consistent with the observations made in the previous literature, a substantial proportion of the new elites who made their way into the mainstream of South Korean politics following democratization did in fact harbor nationalist sentiments and revisionist attitudes that had been cultivated during the years they had spent struggling against authoritarianism. Many of them alleged that the United States had supported the previous authoritarian regimes and, by extension, the oppression and violence they had practiced on their own citizens. Thus, as Ki-Wan Lee notes, if the progressive leaders who gained power with the victory of Kim Dae-jung in 1997 did not advocate outright anti-Americanism, they at least sought to “maintain a certain distance” between themselves and the United States.[xl]

Moreover, while many of these elites were more or less sincere about their nationalistic beliefs, some also found it politically useful to position themselves publicly against the United States and arouse mass sentiments against the ROK-US alliance. “In so doing,” Dong Sun Lee writes, “they could accuse old pro-alliance elites of succumbing to sadaejuui (serving great power)….new elites thus countenanced or even instigated public outbursts of nationalist sentiments for electoral gains.”[xli] Simply put, democratization had decreased the benefits of supporting political compromises on critical national agendas for individual politicians, instead making them more vulnerable than ever to the influence of popular nationalistic sentiments. As a case in point, when a massive wave of “candlelight protests” erupted in late 2002 over an incident in which two teenage girls were accidentally run over and killed by a US armored vehicle, then-presidential candidate Roh Moo-hyun won a surprise victory on what was regarded by many as an essentially anti-American platform. Mainstream politicians generally remained silent on the agitations or gave support through various means, even when they were accompanied by illegal protests or the mass circulation of misleading, exaggerated, or false claims regarding the incident. While, as Yang-sup Shim argues, it would certainly have been desirable for political elites to urge restraint and put forth more determined efforts to keep the protests under control, most simply could not afford to do so lest they undermine their own political standing or opportunities for re-election.[xlii]

Undergirding this political trend was the unprecedented empowerment of special interest groups—including intellectuals, activist organizations, and media outlets—that were hostile to the traditional role of the United States in South Korean politics or sought to use alliance-related issues to further their own political agendas. As Byung-Kook Kim observes,

wherever and whenever U.S. military troops became an issue, an NGO sprang up, networked with already existing activist groups into a broad but loose coalition, and launched its own media campaign by setting up a website, uploading defiant ideas onto other sites’ opinion pages, and urging netizens to join in political demonstrations.

Online news sites operated by NGOs such as Ohmynews and Pressian became highly accessible vehicles for the dissemination of anti-American or anti-alliance ideas. These sites gained a substantial following among the youth who, weary of conservative newspapers such Chosun Ilbo and Donga Ilbo that had traditionally dominated South Korean media, had been eager for “new ways to express, exchange, and develop ideas.”[xliii] In short, the activist groups took full advantage of the new opportunities and capabilities generated by institutional opening and the IT revolution. Just as South Korea’s new elites often found it politically advantageous to advocate revisionist positions in regards to the ROK-US security relationship, the new interest groups found that leading the politicization of alliance issues “[offered] an ongoing platform with which they [could] remain in the political spotlight and continue to develop their organizations during this period of democratization.”[xliv]

The collective impact of these new forces in the nation’s political environment led to a number of high-profile policy moves that seemed to reflect an overall decline of commitment to the ROK-US security relationship on the part of the South Korean government. As a case in point, the ROK government actively engaged Pyongyang with a view to enhancing “national solidarity (minjok gongjo),” apparently at the expense of policy coordination and collaboration with the United States. As a part of the Kim Dae-jung government’s famous “sunshine policy” and Roh Moo-hyun’s “policy of peace and prosperity,” South Korea supplied the North with generous material aid of over 8.8 billion dollars between 1998 and 2008, and pursued various cooperative initiatives such as the establishment of an industrial complex at the North Korean city of Kaesong and a tourist region at Mount Kumgang.[xlv] Such overtures by Seoul to promote inter-Korean reconciliation engendered a considerable level of friction within the alliance, as Washington preferred that aid to North Korea be granted on a conditional basis and in concert with other efforts to induce change in Pyongyang’s behavior (e.g. economic sanctions), especially in regards to its nuclear and missile development. Even after North Korea conducted its first nuclear test in October 2006, the ROK government insisted that cooperative projects such as those at Kaesong and Mount Kumgang continue, to the dismay of US officials.[xlvi]

Aside from assertively pursuing engagement with the North, political leaders in Seoul also promoted policies that were meant to directly address the nationalist desire to put the ROK-US relationship on a more equal footing. For example, upon inauguration President Roh demanded the revision of the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) between Seoul and Washington, which had become a key political agenda for the nationalists after the death of the two schoolgirls in 2002. Many of Roh’s nationalist supporters despised the fact that the SOFA granted to US courts primary jurisdiction over US Forces, Korea (USFK) service members in criminal cases that involved acts committed while on duty.[xlvii] Although SOFAs in other countries and international norms in general recognized the right of the “sending state” to exercise primary jurisdiction in such cases, the nationalists maintained that the SOFA was a fundamentally unfair document that epitomized the unequal relationship between the ROK and the US.[xlviii]

Most significantly, on various occasions the ROK government seemed to place greater policy priority on gaining autonomy from the United States than maintaining the close bilateral partnership that had been carefully cultivated during the period of South Korea’s modernization. This apparent tendency became especially salient during the period of Roh Moo-hyun’s presidency, when the ROK government translated the emphasis on autonomy into a bold policy initiative by asking the US for the return of the authority to exercise operational control (OPCON) over the ROK armed forces during wartime. As I will elaborate in the next section, the request essentially reflected a desire to do away with the highly integrated wartime command structure of the alliance in favor of a more “autonomous” or “independent” command structure. Of course, the proposal was sometimes explained in strategic terms, citing the elevated international status and capabilities of the ROK and the changes in its regional security environment.[xlix] However, the fact that the transfer of wartime operational control was seen by many progressives as a crucial step towards recovering “national sovereignty over military affairs,” and that Roh himself spoke of the transfer and its attendant initiatives as an effort to “break the [ROK’s] psychological dependence and state of dependence” on the United States suggests that it was principally motivated by nationalist idealism rather than acute strategic calculation.[l] In short, if the ROK’s political leadership had previously pursued the integration of the ROK and US military command structures as a means to institutionalize US involvement in South Korean security, they now sought “autonomy” at the expense of that close integration.

As a result of the bilateral frictions generated by these and other changes in South Korea’s attitude and policy behavior toward the United States, the solidarity of the ROK-US alliance suffered a visible decline. With key elements of the South Korean leadership apparently being uncommitted or even hostile towards the bilateral security relationship, many officials in Washington and American public opinion likewise grew increasingly lukewarm toward the prospect of continued US military support for South Korean security. Just as some South Korean politicians had not hesitated to make public their feelings of resentment or criticism against the US, a number of key American officials more or less bluntly expressed their displeasure at ROK conduct and a willingness to reconsider US policy in the region in view of the apparent changes in South Korean sentiments. For example, in January 2003 former secretary of state James A. Baker III told the New Millennium Party chairman Han Hwa-gap during his visit to Washington that “when Corazon Aquino asked U.S. military troops to leave, we left without any second thought…the same is with Korea.” Secretary of defense Donald H. Rumsfeld reportedly stated in a separate conversation with ROK officials that “many Americans will welcome military withdrawal from South Korea.”[li] As the perceived rift between Seoul and Washington continued to widen, some observers warned that it would be only a matter of time before the “requiem” of the alliance would be heard.[lii] Democratic transition had brought back society—or more specifically, competing societal preferences—as a force to be reckoned with in the realm of foreign policy, to the detriment of the ROK-US security relationship.

State-led Efforts for Alliance Revitalization

As described above, the ROK-US alliance underwent considerable turmoil as a result of South Korean democratization. Yet in retrospect, it is obvious that the forces unleashed by democratization have failed to break or even significantly weaken the alliance. Indeed, it is safe to say that South Korea’s commitment to the alliance has experienced appreciable revitalization after what has turned out to have been a brief period of uncertainty. The substance of this revitalization will be examined in the analysis of several major South Korean policy decisions that will follow shortly. Before doing so, however, it is useful to briefly review its main causes.

The reaffirmation and reinforcement of the ROK’s commitment to its alliance with the United States attests to the considerable power and autonomy that has been retained by the South Korean state vis-à-vis societal forces in the post-democratization period. During its period of modernization, the experience of the Korean War and a continuing situation of security vulnerability contributed to the formation of what some scholars have referred to as an “overdeveloped state”—that is, a state that exercised a high degree of control and dominance over civil society—in South Korea.[liii] While democratization invariably led to the decline of the state’s traditional power as a political actor, it is nonetheless meaningful that the democratization process took place within the context of strong, well-developed state institutions. South Korean central decision-makers retained predominant roles in foreign policy decision-making process, and thereby were able to reassert the primacy of the national interest over particularistic societal concerns.[liv]

What has been the nature of the state’s power and preferences in post-democratization South Korea? Three points deserve emphasis. In the first place, a central component of the ROK state’s capability after democratization is the lingering power of the president in national policy-making. While the crux of the democratic reforms of 1987 was the selection of the president through direct nationwide elections, the amended constitution continued to endow the democratically elected president with a remarkable amount of power vis-à-vis the national assembly or its constituent political parties. Particularly in matters of national security and foreign relations, the president acts as the de facto initiator and ultimate leader in virtually all key decisions, negotiations, and legislative acts. Indeed, the preeminent role of the president in national policy has prompted intellectuals and the media to frequently criticize the office and its incumbent as the “imperial presidency,” and lament situations in which the National Assembly acts as a mere “rubber stamp” for the president’s policy decisions.[lv]

Second, even in foreign policy issues that are characterized by a high degree of public salience, the specific content of the relevant policy decisions have largely remained the prerogative of central decision-making bodies that enjoy a high degree of insulation from particularistic societal pressures, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of National Defense, or key bureaus under the control of the Blue House. As such, the aforementioned report by the US Congressional Research Service observes that “the president and the state bureaucracy continue to be the dominant forces in South Korean policymaking, as formal and informal limitations prevent the National Assembly from initiating major pieces of legislation.”[lvi] Such tight control maintained over the substance of policy by the state has been especially important in pushing ahead with controversial or unpopular decisions and mitigating the damage incurred by major policy proposals—such as “wartime OPCON transition”—that are often difficult to retract due to the popular nationalistic sentiments or special interests that become attached to them.

Finally, the persisting North Korean military threat was a key factor that determined the direction in which central state actors steered South Korea’s foreign policy. Possessing the world’s fourth-largest standing military at 1,190,000 active-duty manpower, the DPRK has maintained constant numerical superiority over the ROK in terms of conventional military forces in the post-Cold War era, a substantial proportion of which are forward-deployed in order to enable swift and devastating attacks on South Korean territory. During the past two decades, North Korea has also steadily reinforced a wide range of “asymmetric capabilities”—including the world’s largest special-operations force, long-range artillery that pose a direct threat to Seoul, and a formidable stockpile of chemical and biological weapons—in which South Korea already has a marked disadvantage.[lvii] To make matters worse, the North’s military power has been vastly amplified in recent years with the materialization of Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions. Without a firm security guarantee by the United States, complete with its “nuclear umbrella,” the North Korean regime’s nuclear weapons would grant it a decisive upper-hand in the inter-Korean balance of power by allowing it to effectively hold the entire South Korean population hostage. Such military capabilities have provided the basis of a vast and growing list of rhetorical threats and localized military provocations against the South, which make clear that North Korea’s aggressive intent has not changed in the post-Cold War era.[lviii]

The reality of the North Korean threat reinforced the pragmatism of South Korea’s central decision-makers, and their views and policies accordingly became more alliance-centered over time. Notably, as Dong Sun Lee argues, even the ex-progressive activist Roh Moo-hyun came to adopt more pragmatic positions toward the United States as he gained political experience, largely because even he “could not disregard the North’s military strength altogether.”[lix] Tasked with ensuring the long-term welfare of what undeniably remained a small, weak state in a region characterized by intense security competition, South Korean central decision-makers had no choice but to come to terms with the insuperable limitations of “self-reliance,” and by extension, the need to maintain and strengthen the ROK-US alliance.

Recognizing the state as an independent and, in a crucial sense, rational actor that can define and pursue the national interest in view of its position within the international environment helps make sense of the overall character of Seoul’s behavior towards Washington in the aftermath of democratization. Although there have been limited attempts to realize newly invigorated nationalist visions in the ROK-US bilateral relationship, concrete policy decisions made by Seoul’s central decision-makers indicate that their foreign policy priorities have not been fundamentally altered; rhetoric aside, they have consistently identified the prospects of South Korea’s political integrity and continued national development with the strength of its security relationship with the United States. This is made clear by the three examples discussed below: first, President Roh Moo-hyun’s pursuit of a free trade agreement with the United States; second, Seoul’s efforts to reconcile its policy with the requirements of US military strategy at both the regional and global levels; and third, the development of what came to be known as the “wartime OPCON transition” plan after it was originally proposed in 2003. All three involve policies initiated during the period of Roh Moo-hyun’s presidency, which is widely regarded as the time during which “progressive” clout within the ROK’s political atmosphere was at a historic high. Moreover, all three deal with highly politicized issues that attracted enormous attention from domestic societal actors, and remain subjects of intense controversy in South Korean political debates to this day. As such, taken together, these examples of Seoul’s policy behavior toward the United States demonstrate the autonomy and power exercised by the ROK state in the foreign policy decision-making process, and how its perception of the surrounding strategic realities are translated into active attempts to strengthen the ROK-US alliance.

The ROK-US Free Trade Agreement. Notwithstanding his anti-American image and the consistent emphasis he placed on progressive economic policies, President Roh made the landmark proposal to enter bilateral negotiations for a free trade agreement with the United States (KORUS FTA) in January 2006. This came as a bitter surprise to many of Roh’s former nationalist followers, who lambasted the initiative as a betrayal of the progressive agenda in favor of a US-friendly, “neo-liberal” market fundamentalism. A panoply of political leaders and civil society organizations who had supported Roh’s presidential campaign during the candlelight protests of 2002 now led demonstrations against his policy in a loosely organized coalition called the “Headquarters of the Pan-national Movement to Stop the Korea-US FTA (hanmi FTA jeojee bomgukbon).” Coupled with dissent from within the government itself, this pronounced opposition dealt a severe blow to Roh’s political support base and turned the KORUS FTA into the single most controversial policy issue of the second half of his presidential term.[lx]

Despite the costly domestic political backlash that it generated, the Roh government pursued the KORUS FTA in a remarkably resolute and coherent manner. Such coherence was enabled in large part because Roh delegated almost complete authority over the ROK approach to the negotiations to a small group of experienced officials within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Particularly instrumental in this regard was Roh’s trade minister Kim Hyun-jong. Appointed as the chairman of the newly established “FTA Promotion Committee” via presidential directive on June 8, 2004, Kim exercised overarching control over all aspects of the government’s policy for bilateral trade agreements, including (1) formulating the government’s direction and strategy for the FTA negotiations, (2) assessing the value of establishing an FTA with any particular nation or region, (3) drafting the FTA itself, (4) evaluating the effects of any particular FTA on domestic industries and formulating necessary complementary measures, and (5) supervising the public relations effort to build national support for the FTA.[lxi] Given these comprehensive and far-reaching powers, Kim orchestrated the Roh government’s overall policy on bilateral trade agreements from the time he took office as minister in July 2004 until the conclusion of the KORUS FTA negotiations three years later. While the resulting draft agreement would still need to be ratified by the National Assembly, the members of its various committees and other governmental bureaus were institutionally barred from making significant inroads into the negotiation process itself.

Aside from entrusting the implementation of his decision to a central state body that was highly insulated from extraneous pressures, Roh often used his political clout as chief executive to expedite the negotiations. He did this mainly by communicating to the relevant actors—both domestic and foreign—of the immense priority he was placing on bringing about the FTA. At one point, Roh urged Kim Hyun-jong to “negotiate with an all-business attitude, and never worry about alliance issues or political factors,” since he would be “taking on all political responsibility.” Furthermore, during crucial points in the negotiation process, Roh personally supported Kim’s efforts by directly collaborating with President Bush via telephone, reassuring his counterpart in Washington of his dedication to drafting the agreement.[lxii] Such efforts at reassurance significantly contributed to a favorable policy outcome by convincing Roh’s officials that their political livelihoods depended on the success of the negotiations, and US partners that their investments in the negotiation would not come to a dead end. On the basis of this streamlined process, South Korea succeeded in settling the terms of the highly complicated bilateral agreement with the United States on April 2007—a mere fourteen months after the first negotiations had officially begun.[lxiii]

As such, the key driving force behind South Korea’s pursuit of the KORUS FTA was President Roh’s capability and willingness to override domestic opposition in order to secure the national interests that were tied to the deepening of trade relations with the United States. What did such national interests consist of? It is easy to understand that, from an economic standpoint, the FTA was promoted as a decisive opportunity to stimulate much-needed structural adjustments in South Korea’s domestic industries and to secure continued national competitiveness in a globalizing world economy. In the midst of a global trend for the negotiation of bilateral trade agreements (which began after a major World Trade Organization-centered effort at multilateral compromise floundered in September 2003), Roh saw the KORUS FTA as the first in a series of bilateral agreements that would help secure stable export markets and provide the competitive pressure needed to encourage industrial innovation and growth.[lxiv]

There is no question, however, that the Roh government also pursued the KORUS FTA with exceptional vigor because it viewed the agreement as a practical means to strengthen the ROK-US security relationship. While Roh took care to exclude this aspect from public statements of the rationale for the FTA for fear of undermining the ROK’s position in the bilateral negotiation process, the fact was that the security dimension of the KORUS FTA was so prominent that the agreement was sometimes referred to as an “economic alliance with the United States.”[lxv] There was a widely held expectation that the KORUS FTA would reinforce US commitment to South Korean security by increasing the level of economic interdependence between the two countries. Enhancing bilateral ties in such a manner was seen as especially important in view of the tensions that had characterized the alliance during the early days of Roh’s presidency. Indeed, the fact that the ROK government decided to resume imports of US beef and agreed to the reduction of the so-called “screen quota” for American films as a part of the FTA despite the outcry that such decisions were bound to raise among influential domestic interest groups suggests that, in addition to expectations of economic benefits, alliance considerations were critical to the calculation of ROK decision-makers.[lxvi] That the timing of the presidential approval and subsequent negotiations for the FTA coincided with a period spanning highly-publicized international developments—including the conclusion of the fourth round of the so-called “Six-party Talks” in September 2005, the first North Korean nuclear test of October 2006, and the beginning of consultations on the wartime OPCON transition initiative—also indicates that Roh and his key officials pursued the agreement with a high sensitivity to its alliance-strengthening potential.[lxvii]

In sum, the ROK government’s decision to pursue an FTA with the United States can be regarded as a state-led effort to strengthen the ROK-US alliance. Identifying a core national interest in a closer economic and political relationship with the United States, President Roh sought to augment bilateral ties through what was arguably the single boldest foreign policy initiative of his presidency. Societal opposition against the initiative was overridden through assertive presidential leadership, and by concentrating the relevant decision-making authorities within a highly insulated policy arena—that is, a key bureau within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The strength of this interpretation becomes obvious when one considers that the centralized, “closed” manner in which the KORUS FTA initiative was carried out soon became a major target of criticism from the nationalist opposition.[lxviii]

Accommodation of US Strategic Requirements. In the post-Cold War era, and especially after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Washington sought to adjust its military postures and capabilities to enable flexible and effective responses against newly emerging threats, including both “rogue states” and non-state actors (i.e. terrorist organizations) that might seek to acquire and use weapons of mass destruction.[lxix] This led to two developments in US policy that had heavy implications for the ROK-US alliance. In the immediate term, the US continued to wage its “War on Terror” through large-scale military operations in the Middle East, presenting its allies with perplexing questions on how to adjust their moral and material support for Washington’s war efforts. In the longer term, the US planned to shift the focus of its global military posture away from the stationing of large, permanent forces in key locations abroad in favor of a “rotational presence in smaller facilities that impose less of a footprint on the host nation.” The intent was to transform US forces deployed in each major region to take on a more flexible and expeditionary character, ready to respond to a wide range of unspecified threats on the basis of “capability, not mass.”[lxx] In line with such shifts in its strategic thinking, Washington began to redeploy USFK troops stationed north of Seoul to bases located in South Korea’s rear area, such as Osan and Pyeongtaek, in order to “make it easier for the USFK to be sea-lifted or airlifted swiftly for out-of-peninsula missions.”[lxxi]

Such prominent changes in US global and regional strategies caused substantial controversy in South Korea. To begin with, South Korean non-governmental organizations and progressive politicians joined popular movements around the world in opposing the US-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. When the South Korean government began to review the possibility of dispatching troops to support the US war effort, a large number of civil society organizations and national assemblymen from both the opposition and ruling parties mounted a series of mass protests across the country, turning troop dispatch into a highly salient political issue.[lxxii] Aside from opposing the wars, nationalist intellectuals also leveled vicious criticisms against the broader trends in US military strategy toward Northeast Asia and the Korean peninsula. For example, they argued that accommodating US efforts to task the USFK with wider regional functions would increase the risk that the ROK might become “entrapped” in a regional conflict against its will. In addition, some feared that the southward redeployment of the USFK would increase the likelihood of US preemptive strikes against North Korea, as its troops would be moved outside the range of North Korean artillery.[lxxiii]

Yet, precisely because it was perceived to have such potentially costly implications in terms of domestic opinion and perhaps even short-term security interests, it is all the more remarkable that the ROK adopted a basically accommodative stance toward America’s strategic decisions. In the first place, after a shared understanding on its importance was confirmed through a series of meetings between the ROK Defense Minister and the US Secretary of Defense, final agreement on the “strategic flexibility” of the USFK was issued by ROK Foreign Minister Ban Ki-moon and US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in January 2006. It followed that Seoul would cooperate with US efforts to reconfigure its regional force posture and accept greater burdens for defending against the North Korean threat (which by implication also meant that the ROK would continue to provide increased financial support for the US military presence on the peninsula).[lxxiv] Incidentally, the agreement drew criticism for not having been subject to approval by the National Assembly despite the substantial changes it would entail for ROK-US security cooperation.[lxxv]

The ROK also committed a significant number of its troops to aid the stabilization effort in Afghanistan and Iraq through a number of separate decisions. Among these, especially important was the Roh government’s decision in February 2004 to dispatch a reconstruction support division consisting of approximately 3,000 troops to Iraq, making it the third-largest contributor in the US-led international coalition.[lxxvi] Although the so-called Zaytun Division’s unprecedented size and the fact that a substantial number of troops that comprised it were drawn from combat-oriented forces—such as the Special Warfare Command and the Marine Corps—ignited particularly fierce resistance from hundreds of progressive organizations and national assemblymen,[lxxvii] President Roh succeeded in amassing enough support from key political actors to gain approval for the dispatch from the National Assembly. Especially crucial in this regard was his success in persuading the ruling Uri Party, which had opposed the dispatch due to ideological reasons despite the fact that it had originally entered the political arena as a party comprising Roh’s core progressive supporters. As a forty-member minority party, the Uri Party was a beleaguered group within the National Assembly, regarded with high suspicion by both the conservative Grand National Party and the progressive Democratic Party which it had split away from. It thus had little choice but to enhance its prospects of political survival by cooperating with the President’s initiative, despite its vaunted commitment to progressive ideology.[lxxviii]

South Korea’s accommodation of US strategic requirements, as shown in its acceptance of strategic flexibility for the USFK and large-scale commitment of troops to Iraq, must be understood as an attempt to preserve and strengthen the ROK-US alliance. As Jae-Jeok Park notes, failure to cooperate with America’s core military strategy has led to the de facto discontinuation of the US alliance with some countries in the past, as New Zealand found when it attempted to undermine Washington’s extended deterrence strategy by placing a ban on the visit of US nuclear-capable assets to its bases. In view of such precedents, ROK policymakers seem to have recognized that they could risk the irreversible deterioration of bilateral ties by refusing to cooperate with US efforts to achieve strategic flexibility on the Korean peninsula. “From the South Korean perspective,” Park correctly observes, “the fear of alliance entrapment resulting from accepting USFK flexibility was a distant prospect—but the loosening of the US-ROK alliance was a serious concern.”[lxxix] Similarly, key officials in Seoul viewed troop dispatch to Iraq as a means to secure deeper US involvement in South Korean security affairs, particularly in regards to dealing with the issue of North Korean nuclear development.[lxxx] The following comment made by Roh Moo-hyun in the aftermath of his term neatly illustrates this reasoning:

Someone who is not the President is free to have any opinion on it. But the President must work to maintain that indispensable friendly relationship between the ROK and the US….later, the Zaytun unit provided sizable emotional leverage as we tried to tackle various pending issues in the ROK-US relationship.[lxxxi]

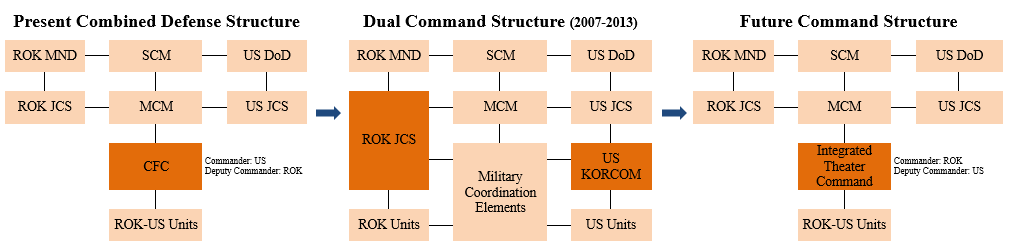

Changes in the Wartime OPCON Transition Plan. In 1978, Seoul made an effort to firmly institutionalize the ROK-US security relationship by leading the establishment of the Combined Forces Command (CFC), which transformed the alliance’s main war fighting headquarters into an integrated command system—similar to the NATO in Europe—composed of more or less equal numbers of ROK and US military staff and yet still headed by an American general.[lxxxii] President Roh’s request for the “return” of wartime operational control in 2003 essentially called for the dissolution of this integrated command system and its role in the alliance’s wartime military operations.[lxxxiii] According to Roh’s nationalist supporters, the integration of ROK-US command structures within the US-led CFC constituted a fundamental infringement upon South Korea’s national sovereignty, and made it likely that US interests would be prioritized over ROK interests in the event of a war. As such, the transition plan agreed to between the ROK and the US during the period of Roh Moo-hyun’s presidency envisioned replacing the CFC with two separate command organizations, with the ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff “leading” wartime operations on the Korean theater and a future “US Korea Command (KORCOM)” taking a “supporting” role. “Military coordination elements” would be established across individual units and functions to handle the bilateral coordination and collaboration currently ensured by the integrated command structure (see figure 1). In short, as Young-Han Moon argues, the transition implied that South Korea’s defense structure would become fundamentally disentangled from the present “ROK-US combined defense system.”[lxxxiv]

As arguably the boldest and most concrete policy move that arose out of the nationalist fervor unleashed by democratization, Roh’s proposal for wartime OPCON transition generated enthusiastic responses from both domestic public opinion and policymakers in Washington. As mentioned above, South Korean nationalists touted the transition as an affirmation of national pride and sovereignty. The popular perception that the military threat from North Korea had significantly decreased as a result of Seoul’s efforts to promote inter-Korean cooperation and dialogue served to support their claim that South Korea was ready to exercise autonomy in security affairs. Thus, as Roh Moo-hyun himself appears to have genuinely believed, a substantial proportion of the ROK populace came to view the US-led wartime command structure as a symbol of South Korea’s continuing state of “dependency” on the United States, and the transition as a crucial step towards achieving “self-reliance in national defense.”[lxxxv] Interestingly, such domestic enthusiasm was matched by similarly welcoming attitudes from the United States. The George W. Bush administration viewed Roh’s initiative as an opportunity to simultaneously enhance the strategic flexibility of the USFK and alleviate anti-Americanism in South Korean public opinion. The Barack Obama administration has also supported the transition with a similar reasoning, with the added expectation that it would contribute to Washington’s efforts to increase partner countries’ roles in international cooperation and, crucially, reduce defense spending abroad.[lxxxvi]

In recognition of such converging sentiments and expectations, even the conservative administrations that succeeded the Roh administration have, at least in principle, expressed commitment to executing the wartime OPCON transition. Considering the gusto with which the proposal was originally made, there is a real possibility that explicitly advocating an indefinite postponement of the transition or revoking the plan altogether will result in a severe nationalist backlash and even loss of international prestige.[lxxxvii] Barring the outbreak of a severe military crisis on the Korean peninsula, it would be politically untenable for any ROK government or serious presidential candidate to publicly reject wartime OPCON transition as a basically desirable policy goal.

Despite this highly constraining political atmosphere, central decision-makers in Seoul have employed a variety of maneuvers in order to preemptively mollify the alliance-disruptive implications of the original wartime OPCON transition plan, aided by the near-exclusive control they exercise over the substance of the transition policy. Most obviously, they have taken the initiative in continuously delaying the transition period. In 2007, the Roh government reached bilateral agreement with the Bush administration that the transition, complete with the dissolution of the CFC, would take place on April 17, 2012.[lxxxviii] After taking office in 2008, the conservative Lee Myung-bak administration immediately called for a reassessment of this timeline, claiming that it reflected a distorted perception of the North Korean threat and a failure to appreciate the value of strong ROK-US ties. The growing intensity of Pyongyang’s provocative acts—including the sinking of the ROK naval corvette Cheonan that took the lives of 46 sailors—served to bolster Lee’s argument that a 2012 transition would be premature. As such, in a summit meeting in June 2010, the Lee and Obama administrations agreed to push back the transition period to December 2015.[lxxxix] In April 2014, the Park Geun-hye and Obama administrations agreed to reconsider the 2015 timeline as well, citing the deterioration of the regional threat environment that had resulted from North Korea’s development of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles. Then, at the 46th annual ROK-US Security Consultative Meeting that took place in October 2014, the ROK Minister of Defense Han Min-koo and the US Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel agreed on the second postponement of the transition, this time to an unspecified, “appropriate date.”[xc]

The latest agreement to push back the wartime OPCON transition timeline underscores another significant development in Seoul’s approach to the transition initiative. Aside from postponing the transition period, South Korean central decision-makers have also attempted to implement changes in the process and content of the wartime OPCON transition plan itself, with a view to minimizing its debilitating impact on the existing ROK-US combined defense system. At their October 2014 meeting, the ROK minister of defense and the US secretary of defense agreed to “implement the ROK-proposed conditions-based approach to the transition,” as opposed to pursuing it with a view to any strictly designated period. The “conditions” stated in their Joint Communiqué included the acquisition of “critical ROK and Alliance military capabilities,” particularly against the threat of North Korean nuclear weapons and missiles, and a “security environment on the Korean Peninsula and in the region…conducive to a stable OPCON transition.”[xci] Placing the OPCON transition plan into such a framework creates a considerable amount of ambiguity as to when the transition might actually take place, since neither Seoul nor Washington can reliably predict or influence the future course of Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons and missile development, much less devise a “once and for all” defense mechanism against it. At least for the time being, this lends the current combined defense system a considerable degree of stability.

Moreover, preliminary reports issued by the Ministry of National Defense state that a revised plan on the alliance’s post-OPCON transition command structure being refined by ROK and US officials envisions the establishment of an “integrated theater command” that closely resembles the current CFC, albeit with the difference that it would be headed by a ROK general, with a US general as his deputy. Figure 1 illustrates the key features of this newly envisioned structure vis-à-vis its two alternatives: the existing combined defense system centered on the CFC and the “dual command” structure that provided the conceptual framework of ROK-US consultation on wartime OPCON transition between 2007 and 2013. In each structure, the portions in bold indicate the main warfighting headquarters that exercise operational control over the alliance’s military units in the event that war breaks out on the peninsula. While the original “dual command” structure retains the Security Consultative Meeting (SCM) between the ROK Ministry of National Defense (MND) and the US Department of Defense (DoD) and the Military Committee Meeting (MCM) between the ROK and the US Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) as core upper-level bodies for bilateral security consultation, it envisions the ROK JCS and the US KORCOM as two separate theater commands that independently exercise operational control over ROK and US units, respectively, during wartime. By contrast, the new “integrated command” structure unifies wartime operational control authority under a single ROK-US theater command, much like the combined defense system does today.

Figure 1 [cii]

Although it remains to be seen how bilateral discussion on this future command structure will evolve (especially since the timing of its implementation has become uncertain), we can be reasonably certain that the new structure under review contains an intent to extend the core elements of the existing ROK-US combined defense system, even if wartime OPCON transition should formally take place in the near future.[xcii] If the original transition plan agreed to during Roh Moo-hyun’s presidency mainly aimed to increase the “autonomy” of South Korea’s security policy by separating its military command structure from the alliance, a future ROK-US integrated command structure quite explicitly aims to preserve the mutually constraining nature of a combined defense system in order to maintain the institutional framework that ensures the solidarity of the ROK-US alliance.