The Economics of the Arab Uprisings:

Alternative Explanations and Heterodox Perspectives

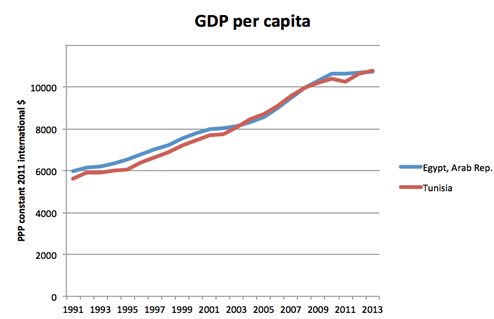

The wave of popular protests that unsettled the mostly autocratic political order of the Middle East in 2011 had its roots in economic concerns. This is palpable from the words of the protesters themselves: “Hosni Mubarak, you agent, you sold the gas and only the Nile is left to be sold” – “I am an Egyptian labourer […] where’s the money the companies are making […]?” (Brynen et al. 213). Early reporting on these protests, that would come to be known as “The Arab Spring”, characterised the movement as an uprising of the poor and poverty stricken whose numbers within society had increased to a point of inevitable retaliation. Despite this pervasive attitude of an overall degradation of the average person’s economic standing, evidence shows that Gini scores in most Middle Eastern countries have actually been improving. There has been an overall improvement in measurable equality in both Egypt and Tunisia since the mid-1970s. Furthermore, according to Figure 1, a steady increase in GDP/capita since the early 1990s is additionally perplexing. Simply, how is it possible that a protest movement, allegedly rooted in grievances over economic inequality and poverty, was initiated at a moment in time when, according to robust indicators, economic conditions in the region had actually been improving? To answer this question, a heterodox economic approach must be adopted that emphasises the “economics of perception”, whereby individual perception of economic conditions may be more deterministic of levels of political mobilisation than the calculated status of those standards.

In these pages, I will situate the 2011 protests within the historical context of the region’s general path of economic development in order to explicate the relationship between past choices by leaders and present responses by the populace. This will lead directly into a section on youth unemployment and its role in motivating protest movements, followed by a more explicit discussion of the economics of perception as they relate to economic inequality and the “flauntiness” of consumption by the political elite. As will be made clear here, “behavioural political economics” has blurred commonly held notions of what truly motivates abrupt instances of political mobilisation. This poses an interesting challenge to the deterministic understanding of classical “rational actor” decision-making, a mantra that has long been essential to contemporary political economic discourse.

Economic Liberalisation in the Middle East: A History of Compensation

The salient economic factors that motivated protest movements in 2011 have their roots deep in the past, initiating from a period a state consolidation in the first half of the 20th century. In the immediate post-colonial period, many countries in the Middle East ascribing by the “state sponsored kick start” theory of economic development began to devote resources and attention to building centralised economic systems, many with a socialist import derived from Nasser’s pervasive Pan-Arabism project (Brynen et al. 217). In this period, “statist economic policies” such as the nationalising of industry and the implementation of subsides on consumer products were implemented as a way of acquiring political support for newly formed states (217). The proliferation of quality education available to all people became a part of this statist model, with the average years of education increasing by 4.1 years in the period between 1970 and 2007 (Dahi 3). In this way, a culture of expectation was established in the region, with the state becoming a paternalistic entity that quickly faltered under the weight of commitments it had made to its now loyal and dependent populations.

A period of economic opening occurred across the region in the early 1970s, in response to declining growth rates and mounting debt brought on by years of unsustainably generous public policies (Brynen et al. 218). A predecessor to more vicious policies of structural adjustment conditionally implemented for IMF loans, the infitah (openness) period spearheaded by Egyptian president Anwar Sadat attempted to invigorate private sector led growth. However, these policies were ultimately co-opted by political considerations, resulting in the engrainment of a network of crony capitalists who enjoyed even greater participation in the policymaking process (Brynen et al. 219). Instead of creating a fertile environment for the expansion of private business, these policies forged quasi monopolies that favoured the ruling elite and prevented new firms from entering the market. With few exceptions, success in the private sectors of Middle East economies came to be determined more by patronage than entrepreneurship (Malik 296). With the glory days of Arab socialism far behind them, Middle East regimes began to find their populations increasingly difficult to satisfy. Expectations developed by the middle-class in the post-independence period became irreconcilable with the outcomes of neo-liberal reforms.

Although the political and economic elite of Middle East countries had achieved economic improvement in terms of statistical indicators (GDP/capita, Gini, etc.), Omar Dahi holds these to have been “Pyrrhic Victories”. Despite achieving economic growth and development in concrete terms, greater contextualisation and qualitative inspection reveals that “by the late 2000s, the Arab States had become virtual oligarchies with an isolated and ruling elite […] and had succeeded in alienating whatever social base they had left” (Dahi 6). It was the common opinion that inequity was the child of wealth being accumulated by the crony capitalist elite through corruptive means (Dahi 6).

Aside from having created a situation prone to widespread feelings of disenfranchisement in its own right, this history of economic development led by concerns for regime consolidation has had several secondary impacts worth noting. The proliferation of subsidisation on consumer products is an accessible method for autocrats to buy themselves political support, by making the cost of living in their country more reasonable. However, as has been the case in most Middle Eastern countries, the political benefits of this system rarely outweigh the negative economic consequences. It is difficult for a regime to remove subsidies once they are in place without popular resistance, as a price expectation is solidified through subsidisation, a change to which will frustrate consumers. In Egypt, where subsidisation of fuel alone eats up 20% of the state budget, measures to phase out subsidisation in early 2012 were abandoned due to pressures from consumers (Halime). Egypt has also maintained a longstanding reliance on food subsidies to ensure stability. However, by 2010 the country was subsidising bread by about three billion USD a year and was importing roughly half of the population’s intake of nine billion tons (Ciezadlo). When the Arab Spring erupted in Egypt, the rising cost of food even with subsidisation was a popular grievance being vocalised by the movement. This case of the “subsidy trap” highlights the shortsightedness of this economic tool to gain regime support.

Another damaging legacy of the development path pursued by many countries in the region is the continuation of a bloated and unsustainable public sector. Since independence, most Middle Eastern countries have used the public sector as a means of bolstering economic development in the absence of institutionalisation (Said 93). Since then, the public sectors of the Middle East economies have grown to be larger than those of the OECD economies, with the government continuing in their role as the preferential employer (Said 99). This, coupled with an underdeveloped private sector, has provided few opportunities for highly educated young graduates to enter the labour market.

Youth Unemployment and Political Mobilisation

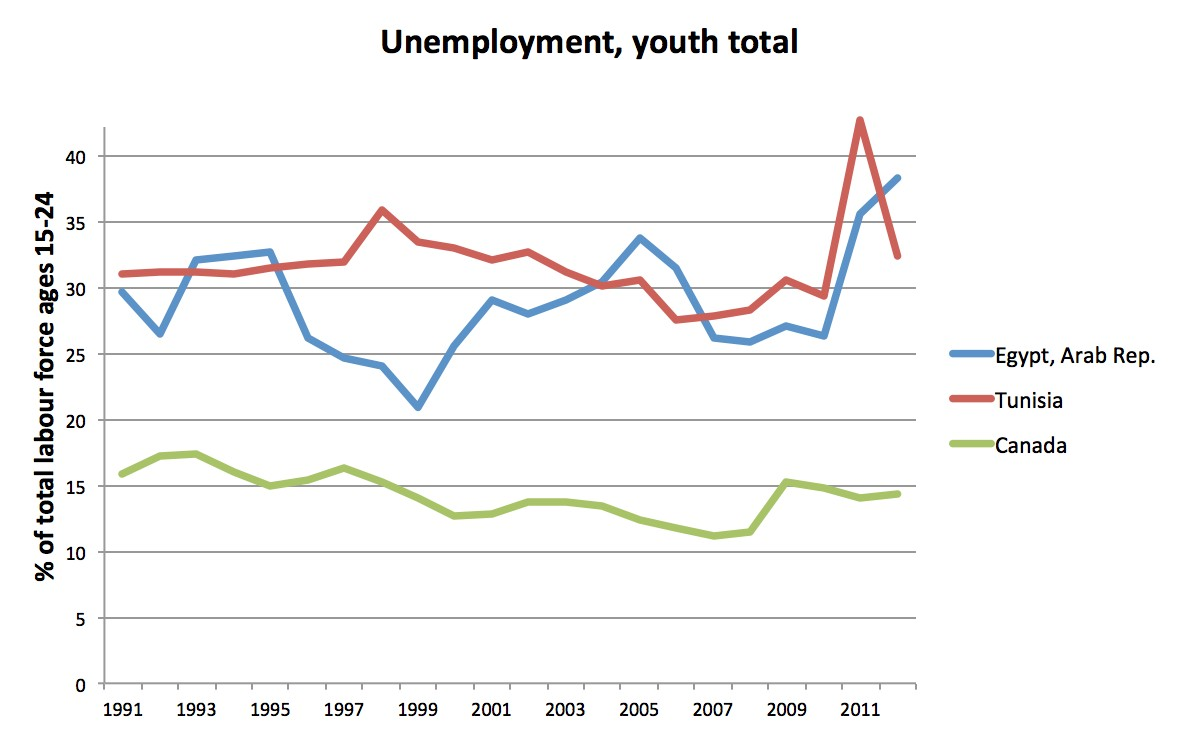

With high salaries, attractive benefits, and job security, public sector employment has typically been the way in which recent graduates desire to enter the workforce in Middle Eastern countries. Indeed, it has been observed that the public sector is the only sector in which many graduates search for jobs, as it is perceived almost as their right as a citizen, with many youth deciding to wait for public sector employment to open up instead of pursuing the few jobs that exist in the private sector (Said 117). However, as larger flows of graduates enter the labour market, this promise of public sector employment can no longer be sustained (Achy 9). This combination of high education, high expectations for sophisticated entry-level positions, and zero or negative growth in labour market demand has resulted in a politically dangerous unemployment gap in many countries in the region (Achy 3). Figure 2 demonstrates this, with the rate of Tunisia unemployed youth peaking at 42% around the time of the popular uprisings. This cohort of frustrated youth became disillusioned by their governments when their education did not secure them the type of job they had been promised (Achy 10). For many, this frustration has been translated into political mobilisation in the form of Arab Spring protests.

To better understand this link between an exasperated unemployed youth population and the propensity to participate in Arab Spring protests, Campante and Chor use an opportunity cost model and survey data to make several compelling claims. According to their study, generally speaking, countries in the Middle East that have increased the average years of schooling also have high degrees of unemployed young people (Campante and Chor 170-73). The combination of high educational attainment, a bleak job market, and high expectations for employment and income yields what the authors see as a low opportunity cost to engage in high intensity political activity such as anti-regime protests (Campante and Chor 175). The authors also note that educated individuals are generally more likely to participate in all kinds of political acts, including political demonstrations “whether because education increases awareness of political issues, fosters the socialisation needed for effective political activity, or generally increases so called civic skills” (Campante and Chor 174). Considering this, it appears that a relatively high degree of youth unemployment in most countries in the region forms a more deterministic motivator for high intensity political protests than a mere degradation of income or equality on a national scale. As Dahi has stated, these gains are best characterised as Pyrrhic Victories, in that they have come at such a high cost in terms of erosion to a social base that the country, from the perspective of the political and economic elite, may have been better off with lower national rates of GDP/capita. Surely, the political costs of this kind of economic development far overshadow any benefits.

Perceptions of Inequality: No “Gini in a Bottle”

While the actual Gini scores for countries such as Tunisia and Egypt had improved in the years prior to the Arab Spring, the claims of protesters points to a high degree of dissatisfaction with the distribution of wealth and opportunity – a degree great enough to prompt political mobilisation. What can be used to explain this? World Bank economist and scholar of global inequality and poverty Branko Milanovic poses the following answer, which tracks the underlying meaning of the “economics of perception”. Despite an actual decrease in economic inequality in most Arab states, the perception of inequality had increased in the period before the Arab Spring. Milanovic sees this process to be exacerbated and accelerated by globalisation and a media network obsessed with the lifestyles of the world’s most affluent. Simply, media is driven by consumer demand, and what consumers demand is information about the “top”. This “top” becomes excessively cognitively and economically distant as a globalised media regime demands to know about who is the best in any respect on the global level. For example, the marginal difference in the skill of the world’s number one tennis player and its hundredth is minimal, but the difference in sponsorship is gargantuan (Milanovic). In this way, the image of being the most successful in any regard, whether it is performance in sport or economic affluence, has a determinative effect on perceptions from below. Increasingly, this distinction between the “haves” and “have nots” has become skewed, with vast numbers of people placing themselves in the “have not” category regardless of their actual position on the global continuum of economic affluence.

Graham and Pettinato characterise this phenomenon in relation to a “frustrated achiever,” whereby relatively economically mobile individuals will look beyond their cohorts to reference their success, oftentimes characterising themselves as much worse off than they really are on a national or global scale. Much like the young Egyptian graduate who feels she deserves a high paying public sector job as her reward for spending time in formal education, the “frustrated achiever” is blind to his own privilege and covets the highest rungs of the socioeconomic ladder. In deeply unequal societies, international consumption standards are adopted, aided by an affluence focused global media, which instil additionally unrealistic economic expectations (Graham and Pettinato 129). In this model, which enjoys evidentiary import from the real world when one looks to the contemporary Middle East, subjective well being is impacted greatly by media and a focus on the global “top”, causing for relative economic standing to be more salient and politically deterministic than absolute economic standing.

Milanovic argues that in the Middle East prior to the Arab Spring, the proliferation of conspicuous consumption by the wealthy elites constituted the prime stimulus for enhanced public feeling of relative and perceived inequality. In the case of Tunisia, seemingly farcical examples of opulence enjoyed by the ruling Ben Ali family became unconcealable to the public as access to the Internet opened the floodgates of information. Soon, most of the country’s tech savvy (and mostly unemployed) youth were aware that the ruling family kept a pet tiger in their beachfront compound decorated with Roman artifacts, and that ice cream and frozen yogurt was regularly flown in from France to impress foreign dignitaries (Freeman). The unacceptability of this kind of conspicuous and unashamed consumption reverberated in social media circles, and further emphasised the depths to which corruption and nepotism had siphoned off much of the country’s capital. Hence, a combination of furry at the status of the elite, along with a general attitude that everyone, even the relatively well off, deserved more, resulted in massive political protests calling for the downfall of the regime in 2011.

To better understand the deterministic power of excessive and widely advertised conspicuous consumption, the inversion of the relationship can be analysed through a discussion of Keynes’ “The Economic Consequences of Peace.” According to Keynes, the pre-WWI elite of capitalist society “preferred the power which investment gave them to the pleasure of immediate consumption” (Keynes 18-19). He portrays this asymmetry of wealth and propensity to invest as the “main justification of the capitalist system,” whereby the public goods generated through investment by the economic elite, such as infrastructure and higher standards of living, could be jointly “owned” by the population as a whole, despite the reality that the vast majority of people truly owned a very small portion of the proverbial capitalist cake (Keynes 19-20). Had the rich in this period “spent their new wealth on their own enjoyments, the world would long ago have found such a regime intolerable” (Keynes 19) as the perception of economic inequality would be intensified through both the lack of public good generation and the establishment of an environment susceptible to feelings of relative inequality and deficiency. In a way, Keynes predicts the societal response to opulence being flaunted by the economic elite, as most Arab Spring protestors indeed found their current regimes to be “intolerable.”

Through this analysis, Milanovic, Graham and Pettinato, and Keynes demonstrate that it is not in an environment of inequality alone that regime threatening economic grievance will fester, but that the behaviour of the wealthy, whether it be the flaunting of their fortunes or the decision to be more discreet, will have a profound impact on the attitudes of the masses. Of course, measuring the degree of “flauntiness” of capital held by the elite in a society is nearly impossible, but this is no reason to ignore the real implications and explanatory power of how wealth is used by a regime’s elite. Certainly there is something that Gini alone cannot explain. It is in this space that the “economics of perception” must be addressed in order to anticipate and respond to situations of politically mobilised perceptions of economic inequality.

Conclusion: The Dawn of Behavioural Political Economics

After the preceding investigation of the history of economic development in the Middle East, the proliferation of youth unemployment in highly educated societies, and the role of conspicuous consumptions by elites, the answer to our guiding question becomes clearer. To understand why the Arab Spring emerged in January 2011, despite the improvement of several economic indicators viewed on the national level, one is forced to engage with the economics of perception. The spread of quality, state-sponsored education across the region, reliance on the public sector to mop up excess unemployment, and the hijacking of a competitive private sector in the interest of maintaining political power all set the stage for the outcomes of the Arab Spring. An unemployed youth population participating in a region-wide unveiling of the conspicuous consumption of elites drew on the history of economic development in the region to motivate political mobilisation. It is undeniable that emotions and perceptions played a central role in the Arab Spring, thus stripping traditional economic indicators of their prescriptive and anticipatory powers. From this analysis, a case for the importance of non-measurable political and economic factors is made. Though the abandonment of a strictly quantitative approach to political economy may be anxiety inducing for proponents of a long lived scholarly tradition, a new heterodox approach that raises qualitative and quantitative data to an equal platform has undeniable benefits for understanding our societies and predicting where they might be heading. I hope that in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, economists begin to adopt a “behavioural political economy” approach to their research that appreciates the economics of perception. Concepts like “flauntiness,” though complex and somewhat amorphous, should be engaged with to give models of economic development a new dynamic of pragmatism. Though heterodox, underdeveloped, and potentially confounding, these approaches to political economy, through an analysis of the Arab Spring, have proven themselves to be salient. They deserve our attention.

Appendix

Works Cited

Achy, Lachen. Tunisia’s Economic Challenges. Rep. Carnegie Middle East Center, n.d. Web. 19 Nov. 2013. <http://carnegieendowment.org/files/tunisia_economy.pdf>.

Brynen, Rex, Pete Moore, Bassel Salloukh, and Marie Joëlle Zahar. Beyond the Arab Spring: Authoritarianism & Democratization in the Arab World. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2012. Print.

Campante, Filipe R., and Davin Chor. “Why Was the Arab World Poised for Revolution? Schooling, Economic Opportunities, and the Arab Spring.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 26.2 (2012): 167-88. Web. <http://wcfia.harvard.edu/files/wcfia/files/rcampante_arab_spring.pdf>.

Ciezadlo, Annia. “Let Them Eat Bread: How Food Subsidies Prevent (And Provoke) Revolutions in the Middle East.” Foreign Affairs. N.p., 23 Mar. 2011. Web. 14 Nov. 2013. <https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/tunisia/2011-03-23/let-them-eat-bread>.

Dahi, Omar. “Understanding the Political Economy of the Arab Revolts.” Middle East Report 259 (2011): 2-6. JSTOR. Web. 11 Apr. 2015.

<http://www.jstor.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/stable/41407959?seq=5- page_scan_tab_contents – page_scan_tab_contents>.

Freeman, Colin. “Tunisian President Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali and His Family’s ‘Mafia Rule’” The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group, 16 Jan. 2011. Web. 12 Apr. 2015.

<http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/tunisia/8261982/Tunisian-President-Zine-el-Abidine-Ben-Ali-and-his-familys-Mafia-rule.html>.

Graham, C., and S. Pettinato. “Frustrated Achievers: Winners, Losers and Subjective Well-Being in New Market Economies.” Journal of Development Studies 38.4 (2002): 100-40. Web. <http://vanneman.umd.edu/socy699J/GrahamP02.pdf>.

Halime, Farah. “Middle East Leaders Cornered by Subsidies.” Financial Times. N.p., 12 Sept. 2012. Web. 14 Nov. 2013.

<http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/720b87e8-fccd-11e1-9dd2-00144feabdc0.html>.

Keynes, John Maynard. The Economic Consequence of Peace. New York, NY: Cosimo Classics, 2005. Archive.org. Web. <https://archive.org/details/economicconsequ01keyngoog>.

Malik, Adeel, and Bassem Awadallah. “The Economics of the Arab Spring.” World Development 45 (2013): 296-313. Elsevier. Web.

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.12.015>.

Milanovic, Branko. “Inequality and Its Discontents.” Foreign Affairs. 12 Apr. 2015. Web. 12 Apr. 2015. <http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/68031/branko-milanovic/inequality-and-its-discontents>.

Said, Mona. “Public Sector Employment and Labour Markets in Arab Countries: Recent Developments and Policy Implications.” Labour and Human Capital in the Middle East. Ed. Djavad Salehi-Ishfahani. Reading: Garnet Limited, 2001. 91-146. Print.

Written by: Stephen Reimer

Written at: McGill University

Written for: Myron Frankman

Date written: April 2015

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Exploring Stratification Economics’ Neglect of Intersectionality

- The Angolan Civil War: Conflict Economics or the Divine Right of Kings?

- Arab LGBTQ Subjects: Trapped Between Universalism and Particularity?

- China’s Increasing Influence in the Middle East

- Drones, Aid and Education: The Three Ways to Counter Terrorism

- Egypt’s Social Welfare: A Lifeline for the People or the Ruling Regime?