This is an excerpt from Nations under God: The Geopolitics of Faith in the Twenty-First Century.

Available now on Amazon (UK, USA), in all good book stores, and via a free PDF download.

Find out more about E-IR’s open access books here.

In recent years, religion has moved from being considered marginal to the study of international relations and global order to assuming an increasingly prominent role in the discipline. The fragile consensus that states were to deal with religion internally began to crumble in the 1990s, and fell apart entirely after 9/11, as experts turned to religion as simultaneously a central problem to be resolved (the agenda of surveillance) and as its own solution (the agenda of reassurance). This is new religion agenda. Tony Blair has described it as the ‘two faces of faith’.[1] This agenda has gained a prominent foothold in contemporary international public policy circles. Good religion should be restored to international affairs, it suggests, while bad religion should be reformed or eradicated. This approach privileges religion as the basis from which to formulate foreign policy, develop international public policy, and orientate human rights campaigns. It organises expert knowledge production and informs government and non-governmental decision-making in contemporary international affairs. It structures the global governance of religious diversity and shapes fields of social, political and religious practice and possibility in particular ways.[2] Following a brief introduction to this framework, this chapter examines the effects of the religion agenda in a specific context, that of Sahrawi refugees living in south-western Algeria, one of many contexts in which the global dynamics of good religion/bad religion have been brought to life. In the process, it introduces an approach to religion and world politics, developed in my forthcoming book Beyond Religious Freedom, that interrogates the distinction between religion as construed for reasons of power, including the good/bad religion framework, and a broader field of social and religious practice of those without it.[3] This juxtaposition offers a glimpse of the politics of global advocacy for religious toleration by revealing the mixed consequences for many Sahrawi refugees of the representation of their camps as ‘ideal spaces’ occupied by religiously tolerant individuals.

The Two Faces of Faith and the Religion Agenda

The two faces of faith serves as shorthand for an interpretive frame, form of expert knowledge, and normative orientation that has provided the discursive scaffolding for much of the so-called return of religion to international affairs over the past two decades.[4] This template pre-structures the field in which many scholars and decision-makers, particularly in Europe and North America, approach and respond to questions involving religion and international public life in scholarly discussions, media conversations, and public policy debates. It serves as a reliable, easy to access language in which to speak about religion that provides a shared point of departure for public policy debates and discussions. It is now often taken for granted in such debates and discussions that irenic religion should be restored to international public life: cementing the moral foundations of international order, providing depth and moral sustenance to claims for international human rights, facilitating the spread of freedom, and promoting human flourishing through advocacy for inter-faith understanding. The return of peaceful religion is lauded as an overdue corrective to secularist attempts to quarantine benevolent religious actors and voices. In the words of Canadian Ambassador of Religious Freedom Andrew Bennett,

In Canada and I’d say the liberal western democracies, we’ve pushed any expression of faith so far into the private sphere in the last half-century or so that we’ve sometimes forgotten how to have that faith-based discourse, and engage faith.[5]

Bennett and other advocates for the religion agenda seek to persuade their listeners that religion and religious actors are especially relevant to global politics because they are uniquely equipped to contribute to relief efforts, nation building, development, and peace building. Good religion is an agent of transformation. It is important and necessary for politics and public life to unfold democratically and for religious freedom to flourish globally. Religion ‘done right’ is an international public good. Tolerant faith-based leaders and authentic religious texts are said to be waiting expectantly in the wings, biding their time while they wait for the public authorities to come to their senses and grant religious voices and actors their proper place in international public life. Religious goods and actors are celebrated as contributors to global justice campaigns, engineers of peace building, agents of post-conflict reconciliation and countervailing forces to terrorism. With a little help from the authorities, the story goes, peaceful religion will triumph over its intolerant rivals.

This conciliatory side of the two faces narrative is reflected in international political projects of striking reach and variety. Global public policy areas subject to this framing include transitional justice efforts, human rights advocacy, development assistance, nation and public-capacity building efforts, religious engagement, humanitarian and emergency relief efforts, and foreign and military policy. Religion appears in this rendering as a potential problem and its own solution, insofar as interfaith cooperation, religious freedom and tolerance can be engendered and institutionalised and extremists marginalised. A proliferating number of generously funded projects are occupied with discerning and engaging peaceful religion and projecting it internationally through states, international tribunals, and international and non-governmental organisations. As this global infrastructure is put in place, a religion-industrial complex is taking shape.

Other global projects, and sometimes the same ones, are consumed by equally pressing efforts to identify and reform intolerant religion and ensure that it is not projected internationally. This less euphemistic side of the ‘two faces’ narrative is concerned with surveilling and disciplining intolerant and divisive religion. When it assumes such forms, it is claimed, religion becomes an object of securitisation and a target of legitimate violence. States are expected to work together with international authorities to contain or suppress dangerous and intolerant manifestations of politicised religion.[6] This fearful, restive religion is associated with the violent history of Europe’s past and much of the rest of the world’s religious present, including the wars of religion during the European Reformation and afterwards, and the intolerance and fanaticism associated with certain forms of what today is often named as religious extremism. Bad religion is understood to slip easily into violence, unlike peaceful religion, which curbs it. Bad religion is sectarian religion, and associated with the failure of the state to properly domesticate it—or, in some cases, of religion to properly domesticate itself.

The two faces of faith reproduce a number of conventions for conceptualising religion that have been discussed and deconstructed in recent years in an impressive literature that spans academic disciplines. Yet it is also distinctive, in some sense, in that religion is not only no longer private—as José Casanova argued in the 1990s—but also takes on specific new forms of publicity, demands new kinds of partnerships and presses forward new agendas with a surprising alacrity and remarkable degree of self-assurance. Initiatives pairing religious institutions and leaders with government offices are being launched, mandates for moral and spiritual reform are drafted and centres for interfaith understanding are built, all with great fanfare.[7] A small army of international public authorities with significant financial means and unflagging political will is awaiting an answer to the question of how to locate and promote tolerant, free religion.[8] Purveyors of the two faces narrative have an answer that has proven compelling to many concerned donors, governments, and other actors: certain religions, and certain forms of certain religions, need to be recognised, reorganised and rescued without delay from secularist condemnation and marginalisation.

Religious inputs and religious actors need to be named, promoted and propelled into the international public spotlight to serve as global problem-solvers. Others need to be disciplined, shunned, or reformed. In this view, religions and religious actors are identifiable. It is obvious who they are. They are inherently different and distinguishable from secular actors. And, importantly, they have allegedly been excluded. My own work questions these claims in favour of an alternative approach to contemporary religion in relation to global politics, law, and society. I have argued, for example, that religion has not been excluded but has assumed different forms and occupied difference spaces in different regimes of governance, often understood as secular.[9] I have suggested that religion might be approached as part of a complex and evolving, shifting series of fields of contemporary and historical practice that cannot be singled out from other aspects of human activity but also cannot be merely reduced to them. I have sought to resist the adoption of any singular, stable conception of religion, instead acknowledging the vast, diverse and shifting array of practices and histories that fall under the heading of religion as the term is used today.[10]

Yet the two faces model retains a certain appeal. It is easy to understand. It provides structure and simplicity for academics, advocates, bureaucrats, journalists, and others struggling to understand a world in which religious leaders, institutions and traditions appear to be gaining significance. It reduces complex social and historical fields, dizzying power relations and diverse and shifting fields of religious practice into a one-size-fits-all policy prescription that meets the needs of those with limited background or interest in religion. The recipe is simple: identify and empower the peaceful moderates and marginalise or reform the intolerant extremists. Many governments, think tanks, foundations, foreign policy pundits and self-proclaimed religion experts traffic in the baseline assumption that when religious moderates are identified and empowered—and fundamentalists identified and reformed—then the problems posed by extremist forms of religion will fade and religious freedom, rights, and toleration will spread unimpeded across the globe. This logic is being institutionalised, to varying degrees and in accordance with local elite sensibilities, in governments around the world, including the US State Department’s Office of International Religious Freedom and, most recently, Office of Faith-Based Community Initiatives. The Europeans and Canadians are not far behind.

An important assumption underlying the two faces discourse is often overlooked in the excitement over the so-called return of religion. The two faces embodies the presumption that academic experts, government officials and foreign policy-makers, especially ‘religious’ ones, know more or less what religion is, where it is located, who speaks in its name, and how to incorporate ‘it’ into foreign policy and international public policy decision matrices. This questionable assumption enables academics, practitioners and pundits to leap straight into the business of quantifying religion’s effects, adapting religion’s insights to international problem-solving efforts, and incorporating religion’s official representatives into international political decision-making, public policy and institutions. And this is precisely what they are doing. Governments, international organisations and even much of the academic literature on religion and international relations treat religion as a relatively stable, self-evident category that is understood to motivate a host of actions, both good and bad.

My book suggests that religion is not an isolatable entity and should not be treated as such, whether in an attempt to separate it from law and politics or to design a political response to it. Any attempt to single out religion as a platform from which to develop law and public policy inevitably privileges some religions over others, leading to what Lori Beaman and Winnifred Sullivan have described as ‘varieties of religious establishment’.[11] Scholars and practitioners working internationally and comparatively need to consider the implications of this critique, and work to embed the study of religion in a series of more complex social and interpretive fields. This requires disaggregating and complicating the category of religion in relation to politics, culture, law and society. It requires considering what the world looks life after we move beyond the ideology of separation. It involves exploring the disjuncture between the forms of official religion that are sanctioned by expert knowledge and produced through specific acts of legal, constitutional and governmental advocacy for religious freedom, tolerance and rights, on the one hand, and the various forms of religion lived by ordinary people, on the other. While these fields overlap and are always entangled with each other, and also with institutional religion, in complex formations, they cannot be collapsed entirely, as is often the case in contemporary international scholarly and policy discussions on religion and politics.

Legal and political advocacy for specific conceptions of religious freedom, tolerance and the rights of religious minorities shape both religion and politics in context-specific and variable ways. These efforts stand neither outside history nor above politics. At the same time, and critically, local practices often work outside of, exceed and confound the utopian legal, political and religious imperatives associated with the ambitious aspirations of the religion agenda. Exploring the consequences of distinguishing in specific contexts between religion as construed for reasons of power, and religion as lived by those without it, calls into question the stability of the category of religion that anchors both the agenda of reassurance and the agenda of surveillance. Attempts to realise religious freedom, religious tolerance and religious rights both shape and constrain religious possibilities on the ground.

The Good Sahrawi and the Politics of Religious Tolerance

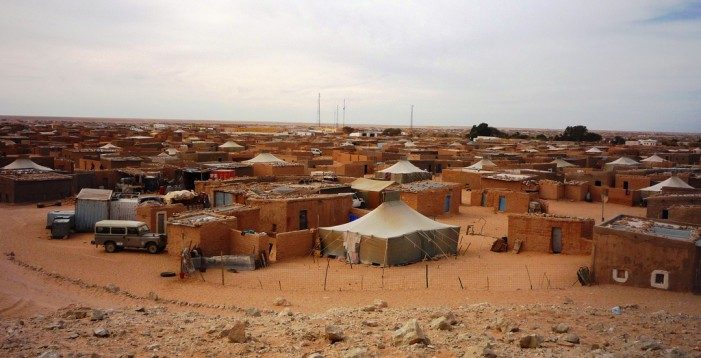

Located in Tindouf province in south-western Algeria, the Sahrawi refugee camps were established in the mid-1970s to accommodate Sahrawis fleeing Moroccan forces during the Western Sahara War. Situated on a flood-prone desert plane known as ‘The Devil’s Garden’ with limited access to water and scarce vegetation, and governed by the Polisario Front, the camps depend almost entirely upon foreign aid. In this context, European and North American constructs of good religion, bad religion, progressive Muslims, religious freedom and inter-faith dialogue—all constructs associated with the religion agenda—have shaped both transnational and intra-Sahrawi politics.

According to Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, the Polisario has

successfully projected the Sahrawi camps as ‘ideal’ spaces inhabited by ‘good’ refugees, in part by reflecting mainstream European and North American normative preferences for the development of a ‘good’ and ‘progressive’ Islam.[12]

In interactions with non-Sahrawi audiences and potential donors, particularly those from Europe and North America, she explains, Polisario leaders make reference to notions of secularism and religious tolerance in an effort to represent the ideal nature of the camps and their inhabitants to audiences that are presumably primed to react positively to these terms. Yet this projection is only one among several different representations of the refugees in the leadership’s repertoire, and which representation is utilised in any given interaction depends on the audience. This strategy enables the Polisario leadership to tap into a substantial and diverse array of political and financial support both inside and outside the camps. Supporters provide material aid and engage in lobbying campaigns in their home countries on behalf of the Polisario’s political objectives. The latter involves most notably the attempt to reclaim a degree of sovereign authority over Western Sahara from the Moroccan government, which has controlled the disputed territory for four decades. From the late 1800s until the mid-1970s, when the Polisario Front launched an armed rebellion, the territory was occupied by Spain and known as the Spanish Sahara. Under pressure from Morocco and the US, Spain reneged on its promise of independence and in 1975 agreed to a joint Moroccan and Mauritanian occupation, later exclusively Moroccan. Half the Sahrawi population subsequently fled into Algeria and became the refugees they remain today. The US continues to support Morocco’s refusal to hold a referendum on independence, while the UN formally recognises Western Sahara as a non-self-governing territory—Africa’s last colony.[13]

From the perspective of the global politics of religious tolerance, the strength of Fiddian-Qasmiyeh’s account lies in her focus on a triangular set of relationships that have evolved between evangelical humanitarian groups (the Defense Forum Foundation, Christ the Rock Community Church and Christian Solidarity Worldwide-USA) that are active in the camps, Polisario leaders and the Sahrawi people.[14] There is a particularly tight connection linking the Polisario and the evangelical humanitarian groups. As Fiddian-Qasmiyeh explains, ‘the Polisario’s determination to activate not only evangelists’ humanitarian assistance but also their political support is arguably, at least in part, as a result of these organations’ proven dedication and efficiency in so prominently lobbying on behalf of “the Sahrawi people”’.[15] The Sahrawi’s purported ‘religious tolerance’ is a critical ingredient in this alliance. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh observes, for example, that Defense Forum Foundation representative and pro-Sahrawi activist Suzanne Scholte:

has widely transmitted accounts of the Sahrawi’s receptivity to Christianity and overarching religious tolerance in the international arena, including before the US Congress and the UN Decolonization Committee on numerous occasions since 2002. … Several other evangelists have lobbied for the Polisario on Capitol Hill and before the UN Decolonization Committee, including (in October 2009) Dan Stanley, senior pastor from RockFish Church, who reportedly led the first prayer session in the camps, and Cheryl Banda and Janet Lenz from Christ the Rock Community Church.[16]

This supportive relationship between the Polisario and their foreign humanitarian supporters also generates particular forms of intra-Sahrawi politics. As Fiddian Qasmiyeh explains, ‘the international celebration of the Sahrawi refugee camps’ success is … directly associated with and even dependent upon the concealment, or discursive minimisation, of everyday Muslim identity, practice and institutions’.[17] Maintaining the appearance of ‘religious tolerance’ depends upon what she describes as a ‘tyranny of tolerance’—or ‘system of repress-entation, which purposefully centralises certain groups, identifiers and dynamics while simultaneously displacing and marginalising those which challenge official accounts of the camps.’[18] Journalist Timothy Kustusch’s description of a 2008 interfaith dialogue session in the camps confirms this, noting that ‘to avoid potential tension, only a few political leaders from the Polisario Front (the independence movement of the Sahrawi people), local religious leaders and volunteers from Christ The Rock were invited’.[19] As Fiddian-Qasmiyeh explains, ‘the Sahrawi ‘audience’ was restricted to those who had already officially demonstrated their allegiance to the official script of “tolerance”’.[20] Dissenting, unofficial scripts were inadmissible. Janet Lenz, founder of Christ The Rock’s Sahrawi project, observed of the session that, ‘while a few of the attendees at the inaugural session did attempt to debate, the proceedings were for the most part peaceful and cordial’. For Lenz, the achievement of tolerance and peacefulness hinge on what Fiddian-Qasmiyeh identifies as ‘the repression of “debate” or contestation on-stage, recreating the camps as spaces of unequivocal acceptance of the religious Other’.[21]

There is an interesting tension between religious tolerance as construed by the Polisario-evangelical axis of cooperation, on the one hand, and those Sahrawis whose ‘individual, familial and collective priorities and concerns may be irrevocably different from those of Polisario and evangelical actors alike’ on the other.[22] This Polisario–international humanitarian axis of cooperation leaves little or no space for dissenting Sahrawi voices to be heard, not only when confronted with non-Sahrawi audiences but also, and critically, within the Sahrawi community itself:

Although the Polisario has the potential to ‘ingratiate themselves’ with their supporters through representations of the camps as unique spaces of religious freedom and tolerance and of ‘the Sahrawi people’ as inherently welcoming of evangelical groups, these performances equally have the potential to create an irreconcilable rupture not only with other, non-evangelical donors (including ‘secular’ Spanish ‘Friends of the Sahrawi’), but also between the Polisario and the very refugees which this organization purports to represent. The enactment of such debates and contestations, however, is suppressed in the camps via strategies of repress-entation which limit the audibility, visibility and very presence of those actors whose individual, familial and collective priorities and concerns may be diametrically opposed to those of key donors and the Polisario alike.[23]

These particular Sahrawi refugees’ lack of voice and agency in these circumstances illustrates who and what is excluded when international religious freedom, tolerance and inter-faith dialogue—and the material benefits that follow in their wake for those in a position to claim them—capture the field of emancipatory possibility as unchallengeable political and social goods in a particular context.[24] These dynamics are central to the politics of the religion agenda, which is distinguished by a strong commitment to the global realisation of these purportedly universal goods and goals.[25]

The diverse experiences and complex power relations uncovered by Fiddian-Qasmiyeh speak to the potential of discriminating analytically between religious tolerance, freedom, and rights as construed by those in power and the practices of ordinary people who are subjected to these techniques of governance. Doing so reveals a gap or tension between expert and ‘governed’ religion—heuristics described in more detail in my book—and the practices of ordinary people who often experience complex and shifting relationships to the institutions, orthodoxies and authorities that allegedly represent them, whether understood as secular, religious or neither. The Sahrawi case also speaks to the transformative effect of a particular conception of ‘religious tolerance’, cemented in a political partnership between external supporters and local Polisario leaders, on the lives of potential dissenters and others not in power, in this case the average refugee. Finally, it attests to the value of attempts to apprehend Sahrawi practices and histories on their own terms, even or especially to the extent that they appear as unintelligible or illegible to legal and normative frames such as religious tolerance or religious freedom, rather than seeking to assimilate them into these templates. This may be, in part, what Markus Dressler and Arvind Mandair are referring to when they call for releasing the ‘space of the political from the grasp of the secularisation doctrine’.[26] Doing so allows us to bring international human (and religious) rights advocacy back into history,[27] acknowledging its debts to particular histories and conceptions of secularity, tolerance, subjectivity and religion. To fail to do so is risk remaining within, and reproducing, the specific discourses of religious tolerance, freedom and rights purveyed by those in power. It risks losing sight of diverse aspects of Sahrawi, and many other histories and experiences, beyond religious freedom.

Note

[1] Tony Blair, ‘Taking Faith Seriously’ New Europe Online, January 2, 2012.

[2] As Courtney Bender observes, ‘insofar as religious “freedoms” appear to operate outside of the articulation of various state powers in social scientific models of religious pluralism, they emerge as free-floating tools, strategies, and “capacities” that can be exported or that can be used to judge the religious lives of individuals and groups in other parts of the world.’ Bender, ‘Secularism and Pluralism’, unpublished paper, June 2012.

[3] Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, Beyond Religious Freedom: The New Global Politics of Religion (Princeton: Princeton University Press, forthcoming 2015).

[4] Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, ‘International Politics after Secularism’, Review of International Studies 38, Issue 5, Special Issue, ‘The Postsecular in International Relations’ (December 2012): 943-961.

[5] Olivia Ward, ‘Meet Canada’s Defender of the Faiths’, The Toronto Star, February 14, 2014.

[6] See for example the Report of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, ‘Engaging Religious Communities Abroad: A New Imperative for US Foreign Policy’, Report of the Task Force on Religion and the Making of US Foreign Policy, Scott Appleby and Richard Cizik, co-chairs (Chicago: February 2010). Peter Danchin sums up the Report’s recommendations: ‘the strategy proposed in the report is thus to continue to kill religious extremists while simultaneously engaging Muslim communities through all possible bilateral and multilateral means—through, e.g., the machinery brought into existence by the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 (IRFA) or international organizations such as the UN and its specialized agencies.’ Danchin, ‘Good Muslim, Bad Muslim’, The Immanent Frame, April 21, 2010.

[7] An example is the KAICIID Dialogue Centre (King Abdullah Bin Abdulaziz International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue), located in Vienna, which according to its website ‘was founded to enable, empower and encourage dialogue among followers of different religions and cultures around the world’. The Centre describes itself, rather improbably, as ‘an independent, autonomous, international organisation, free of political or economic influence’.

[8] In some sense, Casanova’s Public Religions in the Modern World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994) may be seen as having opened the floodgates for public consumption and eventual acceptance of this narrative.

[9] Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, The Politics of Secularism in International Relations (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008).

[10] Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, ‘The Specific Order of Difficulty of Religion’, The Immanent Frame, May 30, 2014.

[11] Lori G. Beaman and Winnifred Fallers Sullivan, eds., Varieties of Religious Establishment (London: Ashgate, 2013).

[12] Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, ‘The Pragmatics of Performance: Putting “Faith” in Aid in the Sahrawi Refugee Camps’, Journal of Refugee Studies Vol. 24, no. 3 (2011): 537.

[13] Stephen Zunes, ‘The Last Colony: Beyond Dominant Narratives on the Western Sahara Roundtable’, Jadaliyya, June 3, 2013.

[14] Working in the camps since 1999, Christ the Rock provides US summer host families for Saharawi children, teaches English in the Smara camp, and develops programs to ‘build bridges between people in the United States and Saharawis forced to live in the arid Saharan Desert’. Timothy Kustusch, ‘Muslim Leaders and Christian Volunteers Host Religious Dialogues in Saharawi Camps’, UPES, April 2, 2009.

[15] Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, ‘Pragmatics of Performance’, 539.

[16] Ibid., 539.

[17] Ibid., 537.

[18] Ibid., 542.

[19] Kustusch, ‘Muslim Leaders and Christian Volunteers Host Religious Dialogues’.

[20] Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, ‘Pragmatics of Performance’, 542.

[21] Ibid 542.

[22] Ibid 544.

[23] Ibid., 544, citing Barbara Harrell-Bond, ‘The Experience of Refugees as Recipients of Aid’, in Refugees: Perspectives on the Experience of Forced Migration, edited by Alastair Ager (London: Pinter, 1999): 136–168.

[24] Wendy Brown makes a related argument in Regulating Aversion: Tolerance in the Age of Identity and Empire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008). For a perceptive attempt to rethink and refashion the theory and practice of tolerance in western democracies see Lars Tønder, Tolerance: A Sensorial Orientation to Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[25] For a reconsideration of these efforts see the publications of the Luce Foundation-supported project, Politics of Religious Freedom: Contested Norms and Local Practices, including the forthcoming volume Politics of Religious Freedom, edited by Winnifred Fallers Sullivan, Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, Saba Mahmood and Peter Danchin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

[26] Markus Dressler and Arvind Mandair, ‘Introduction: Modernity, Religion-Making, and the Postsecular’, in Secularism and Religion-Making, edited by Markus Dressler and Arvind-Pal Mandair (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 18. Dressler and Mandair describe three distinct trajectories in the critique of secularity: ‘(i) the socio-political philosophy of liberal secularism exemplified by Charles Taylor (and to some extent shared by thinkers such as John Rawls and Jürgen Habermas); (ii) the postmodernist critiques of ontotheological metaphysics by radical theologians and continental philosophers that have helped to revive the discourse of political theology; (iii) following the work of Michel Foucault and Edward Said, the various forms of discourse analysis focusing on genealogies of power most closely identified with the work of Talal Asad’. Ibid., 4.

[27] Samuel Moyn, The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2010).

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Chimera of Freedom of Religion in Australia: Reactions to the Ruddock Review

- Secularism: A Religion of the 21st Century

- Opinion – Navigating Epistemic Injustices Between Secularism and Religion

- Religion in International Relations and the Russia-Ukraine Conflict

- Probing the Intersection of Religion, Gender, and Political Violence

- United Moderate Religion vs. Secular and Religious Extremes?