Domestic Workers in the Shadows: A Normative Assessment of Modern Slavery in the UK

The problematic issues addressed by the Modern Slavery Bill 2015 in the United Kingdom have a strong link to the dire predicament faced by domestic workers. Domestic workers are a particularly vulnerable group, whose members are not rarely subject to systematic human rights abuses[1]. Due to the particular conditions surrounding domestic work, which imply various sources of vulnerability[2], exploitative labor practices are often enabled, amounting to present-day slavery or servitude. Despite significant advancements in international law concerning the protection of domestic workers, I argue that the current legal framework in the UK not only falls short of providing them with effective protection from enslavement and exploitation[3], but it also contributes to the furtherance of their victimization, allowing domestic labor to remain in the shadows[4]. In light of this, the envisaged legal remedy is two-fold: firstly, engaging in a serious commitment to human rights by devising an effective legislative scheme that appropriately addresses domestic workers’ vulnerability and places them, at the very least, in equal standing with other workers, thus redressing their legally condoned unequal treatment and bringing about formal equality; secondly, a structural reform is needed towards substantive equality[5], purporting to revert the disadvantage from which their discriminatory treatment stems, by means of revisiting the liberal principle of the public/private divide[6], which is currently used to obstruct legal compliance mechanisms, veiling modern slavery practices in the context of domestic work.

Modern Slavery and Domestic Work: Concept and Theory

Adopting a positivistic approach as a conceptual starting point, the prohibition of slavery under international law dates back to the United Nations International Convention on the Abolition of Slavery of 1926, which conceptualized slavery as the exercise of powers inherent to property or ownership over another person. It stands to reason that any attempt to strictly apply this outdated definition to the present time would be an anachronistic failure, though a critical approach of its provisions is useful, as they convey the abhorrent essence of the practice: the dehumanizing commodification of humanity[7]. The definitional contours of modern slavery as applied to domestic labor were assessed by the European Court of Human Rights (“ECtHR”) in Siliadin v France[8]. The ECtHR relied upon different international human rights instruments, including the legal framework of the International Labor Organization[9], to issue a landmark decision that illuminated how modern slavery is a multifaceted phenomenon[10]. The court distinguished the classical approach to slavery, which involves objectification, from the notion of servitude, encompassing loss of personal autonomy, grave denial of freedom, coercion and extreme dependency on employers[11], in that both concepts fall into the scope of Article 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights (“ECHR”). Furthermore, the court interpreted the ECHR in light of recommendations issued by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe[12], which emphasize domestic slavery as a new form of slavery in Europe that predominantly affects women who come from underprivileged socioeconomic backgrounds and are coerced into working in private households for little or no financial reward, facing all kinds of psychological and physical ill-treatment, as well as many constraints placed upon their freedom of movement.[13] It is vital to note that both slavery and servitude, albeit to some extent distinguishable, refer to the same overarching phenomenon of economic exploitation and forced labor, which is often elicited through a psychological dilemma posed to the worker: either being exploited or choosing material deprivation and destitution[14]. These conceptual clarifications of modern slavery in the realm of domestic labor further enlighten the application of other paradigmatic international human rights instruments[15].

Notwithstanding the illuminating insights provided by the positivistic standpoint, further elaboration is required on the substantive and normative dimensions of domestic workers’ modern enslavement under the labor and human rights theoretical umbrella. Modern slavery or servitude entails a relationship of exploitation and abuse that compromises the core values underlying the right to work: self-realization, self-esteem and dignity[16]. These values are intrinsically intertwined with the conceptualization of work as a meaningful job that allows workers to demand corresponding duties from other people, cooperate inside the community and build significant interpersonal relationships, thereby enabling autonomous and dignified lives[17]. Contrariwise, domestic slaves and serfs live under coercive control and are often isolated, facing economic dependency and different forms of ill-treatment[18], a situation that utterly antagonizes the foundational values of any plausible conceptualization of a human right to work. In addition to the labor-rights dimension, a normative approach, capturing the human rights ambit, firmly buttresses a range of universal and morally compelling rights to which domestic workers should be entitled, e.g., the right to be free from degrading and humiliating ill-treatment by the employer, an abusive pattern commonly identified in modern slavery practices[19]. It is reasonable to assert that no theoretical disagreement could go so far as to deny the high normative and moral relevance of protecting the right not to be exploited and the human right to dignified work[20], ensuing that their breach constitutes egregious human rights violations.

Both international law[21] and scholarly literature[22] explicitly acknowledge the deeply embedded vulnerability of domestic workers and highlight the need to appropriately address their fragile status in national legal orders to ensure their protection from modern slavery or similar ordeals. Modern slavery instantiates one of the paradigmatic evils that human rights so vehemently purports to annihilate, for it curtails their basic capabilities, hindering them from achieving human flourishing by freely living valuable lives of their choosing[23], deprives them of agency, liberty and autonomy[24] and profoundly breaches the core of their human dignity[25].

Structural Sources of Vulnerability

The sources of domestic workers’ vulnerability to abuse or “sectoral disadvantage”[26] are three-fold: social, economic and psychological[27]. Domestic workers are particularly vulnerable to exploitation by their employers because domestic labor is invisible and devaluated[28] owing to structural factors. Under the social dimension, the problem has at its roots the gendered nature ascribed to domestic work[29] i.e., in addition to domestic work often being undervalued and deemed to be menial[30], the majority of domestic workers is constituted by women[31]. In conformity with the deep-rooted patriarchal legacy challenged by feminists[32], domestic tasks are still perceived as an archetypically female domain, falling into the realm of the undervalued “reproductive work” performed by women in the private sphere of the household, as opposed to the highly valued “productive work” carried out in the public sphere of the labor market[33]. As a result of the deeply ingrained social prejudices that guide gender stereotypes, domestic work is relegated to a sub-standard category of work, which reflects on the economic dimension of the issue, namely low salaries. Impoverishment impels domestic workers to be economically dependent on their employers, thereby entailing “bargaining power hipo-sufficiency”[34]. In addition to social and economic aspects that contribute to the vulnerability of domestic workers, the psychological dimension must be underscored, consisting in the sense of intimacy that stems from the peculiar form of employment relationship created[35]. Intimacy often works to the advantage of the employer, who may be eager to pull the domestic worker into the private familial sphere and widen the margin of managerial power, hence reaffirming the status inequality inherent to the relation of subordination rather than establishing the boundaries required in a professional employment relationship, allowing for unbridled subjugation[36]. The social stigma faced by domestic workers instantiates these social, economic and psychological mutually reinforcing mechanisms that create particular conditions of vulnerability to abuse, which is aggravated by the fact that they are hidden away from the public eye.

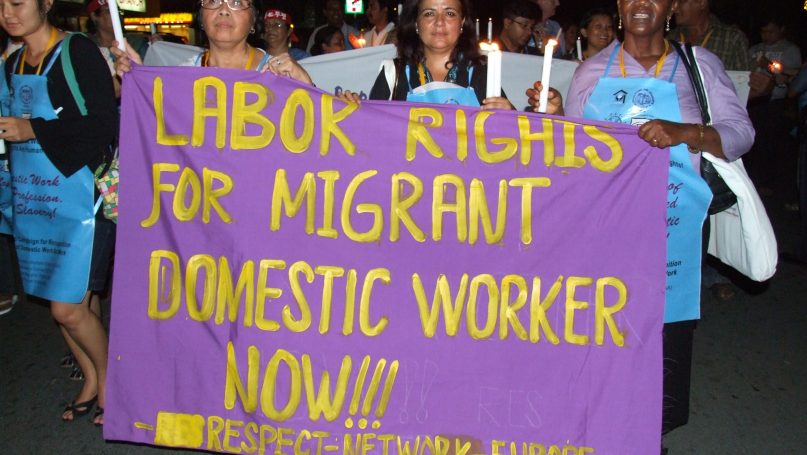

The illustrative case of migrant domestic workers presents even higher normative concern due to the increased vulnerability that arises from their migratory status. Generally speaking, migrant domestic workers originate from developing countries[37] and face, on top of the aforementioned sources of vulnerability, additional difficulties owing to inter alia lack of citizenship, absence of networks of support and extremely underprivileged socioeconomic status, making it harder for them to seek help from authorities when necessary. Immigrants are a historically disadvantaged group that is known to be marginalized and exploited[38], an assessment that also applies to certain racial and ethnic groups. In this sense, intersectional factors of disadvantage often come into play, e.g gender, race and class[39], ensuing certain migrant domestic workers’ aggravated underprivileged status of multiply-burdened subjects. The fact that a significant number is trafficked for domestic servitude[40] also ought to be factored into the equation, resulting in a scenario of extremely vulnerable individuals who are multiply-stigmatized by structural elements, thus requiring an appropriate legal framework of protection to address these issues and prevent further abuse[41]. Nevertheless, the vulnerability of domestic workers, particularly migrants, is reinforced rather than tackled by the current domestic legislation of the UK.

Legal Sources of Vulnerability: Critique and Normative Response

Structural sources of vulnerability are interlocked in a complex and dynamic interplay that perpetuates societal prejudices, contestable values and inadmissible inequalities that, to a large extent, are mirrored in the current legislative framework, which systematically incorporates and reproduces these disadvantages and injustices. As a result, modern enslavement in the context of domestic labor is virtually enabled by the legal-institutional machinery presently set in motion. Under a holistic approach, legislative provisions in the UK fall short of effectively providing the same level of protection attributed to other kinds of work to domestic labor, hence failing to meet the threshold of providing adequate protective standards for domestic workers. The systemic failure of unequal protection by law corresponds principally to the maintenance of the private/public divide, a liberal legal principle that has been the target of compelling attacks by feminist theorists precisely because of its enabling effect on systematic patterns of inequality such as recurrent gendered violence in the domestic sphere[42]. As previously noted, the workplace of the domestic worker overlaps with what is protected by law as the private life of the employer: his private household[43]. This peculiar feature of domestic employment blurs the line between the private and the public to the advantage of the employer, who profits not only from the structural inequalities of the relationship but also from the protection of his intimacy and private life[44]. Upholding the private/public dichotomy translates into the assumption that the private household transcends the boundaries of legitimate State interference and regulation[45], a pervasive principle in law that leaves domestic employment out of reach of protective labor standards and monitoring mechanisms, rendering accountability ineffective. Whilst law shies away from adequately tackling the problem, the power struggle within the employment relation tends to unravel to the detriment of the weaker party[46], as abuses are covered by the veils of privacy and impunity.

A second analytical layer invites a more careful examination of labor, immigration and criminal law provisions in order to assess how individual pieces of legislation address the vulnerability of domestic workers, especially migrants, and to what extent the goals of promoting equality and preventing discriminatory treatment are achieved when compared to other categories of workers. Under this fragmented approach to legislation, problematic legal vacuums can be identified. Firstly, several exemptions from protection are found in laws regulating health and safety standards at work, as well as regulations pertaining working hours[47], resulting in the explicit exclusion of domestic workers from the protective scheme of labor laws[48], hence violating formal equality. Moreover, classifying domestic workers as analogous to family under the law[49] entails the inapplicability of minimum wage standards, allowing for situations of increased impoverishment and economic dependence to the employer. Secondly, under immigration law, the special visa regime for overseas domestic workers ties them to their employers, limiting their autonomy by not allowing them to seek another employer[50]. The dilemma faced by many workers hence becomes either withstanding an abusive employment relationship or being deported to face destitution in their home countries[51]. A third path rests upon illegality as undocumented migrants, aggravating their status of “precarious workers”, i.e., unprotected by law and socioeconomically vulnerable[52], a tough ordeal illustrated by the lengthy and arduous judicial proceedings in Hounga vs Allen[53], a teenage undocumented migrant whose right to receive proper compensation for domestic work was only recognized when appealing to the House of Lords, which overturned previous understandings that the doctrine of illegality prevailed over the statutory tort of discrimination[54]. Thirdly, although modern slavery and servitude have been criminalized[55], the absence of monitoring mechanisms in the realm of domestic work is an obstacle that renders criminal provisions much less effective. The more vulnerable the worker, the fainter the chance of systematic abuse ever being reported, especially in face of the above described “legislative precariousness”[56] i.e., the failure of protective legal norms to treat domestic workers on an equal standing with other workers, either through explicit differentiation or implicit omission. This enables the perpetuation of a vicious circle of vulnerability bolstered by structural factors, especially in the case of migrants.

Therefore, in addition to undercutting legislative exemptions that compromise labor rights protection and bringing about adequate immigration law reforms to mitigate the inherent vulnerability of migrant domestic labor, compliance and monitoring mechanisms must be increased, including making labor inspections and access to adjudicatory proceedings a reality to domestic workers[57], with a view to inhibiting the commission of abuses and ensuring fair and equal protection for this disadvantaged category of workers.

Concluding Remarks

Modern slavery practices disguised as domestic work, an occupation that should be perceived, valued and promoted in consonance with its incommensurate contribution to the global economy[58], is both morally and legally inacceptable in a society that consecrates human rights as fundamental values that must be upheld above all. Under a normative approach of the State’s ethical and moral duties, the systemic legal failure to address domestic workers’ vulnerability and prevent abuses may be reverted by strengthening the equality and anti-discrimination framework in law, under a formal equality approach, as well as pushing forward additional legislative reforms to tackle structural factors of vulnerability that hamper law enforcement efforts, with a view to attaining substantive equality and effectively protecting domestic workers, a vulnerable group that stands on the convergence of multiple grounds of societal vulnerability and discrimination.

References

Anderson B., ‘Just Another Job? The Commodification of Domestic Labour’, in B Ehrenreich, AR Hochschild (Eds.) Global Woman: Nannies, Maids and Sex Workers in the New Economy (Granta 2003).

Anderson B., ‘Migration, Immigration Controls, and the Fashioning of Precarious Work’ (2010) 24(2) Work, employment and Society 300-317.

Bogg A. and Mantouvalou V., ‘Illegality, Human Rights and Employment: A Watershed Moment for the United Kingdom Supreme Court?’ UK Constitutional Law Blog (13th March 2014) available at <http://ukconstitutionallaw.org/> accessed 23 April 2015.

Collins H., ‘Is There a Human Right to Work?’, in Mantouvalou V (Ed.), The Right to Work: Legal and Philosophical Perspectives (Hart Publishing 2014).

Davidson JO, ‘New slavery, old binaries: human trafficking and the borders of ‘freedom’ (2010) 10(2) Global Networks 246.

Fredman S., Discrimination Law (Oxford University Press 2011).

—— , ‘The Role of Equality and Non-Discrimination Laws in Women’s Economic Participation, Formal and Informal’ Report, (Working Group on Discrimination against Women in Law and Practice, UN OHRCHR 2013) available at <http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WG/ESL/RoletEqualityandNonDiscriminationLawsinWomensEconomic.docx> accessed 23 April 2015.

Goldin A., ‘Labour Subordination and the Subjective Weakening of Labour Law’, in Davidov G & Langille B, (Eds.) Boundaries and Frontiers of Labour Law Goals and Means in the Regulation of Work (Hart Publishing 2006), 109-132.

Kalayaan, Report “Slavery by another name: the tied migrant domestic worker visa” available <http://www.kalayaan.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Slavery-by-a-new-name-Briefing-7.5.13.pdf> accessed 23 April 2015.

Lacey N., ‘Feminist Legal Theories and the Rights of Women’ in K Knop (ed.) Gender and Human Rights (Oxford University Press 2004), 13-56.

Mantouvalou V., ‘Are Labour Rights Human Rights?’ 3 European Labour Law Journal, 151-172.

—— , ‘Life After Work: Privacy and Dismissal’ LSE Law, Society and Economy Working Papers 5/2008 <http://ssrn.com/abstract=1111957> accessed 24 April 2015.

—— , ‘Human Rights for Precarious Workers: The Legislative Precariousness of Domestic Labor’, (2012) 34 Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal 101, 133-166.

—— , ‘Modern Slavery: the UK Response’ (2010) 39(4) Industrial law Journal 425.

—— , ‘Servitude and Forced Labour in the 21st Century: The Human Rights of Domestic Workers’ (2006) 35 Industrial Law Journal 395

—— , ‘The Many Faces of Slavery: The Example of Domestic Work’, Global Dialogue, (Summer/Autumn 2012) Volume 14, Number 2, Slavery Today, available at <http://www.worlddialogue.org/content.php?id=536> accessed 23 April 2015.

—— , ‘The Right to Non-Exploitative Work’, in The Right to Work: Legal and Philosophical Perspectives, Mantouvalou (ed) (Hart Publishing 2014), 39-60.

—— , ‘What is to Be Done for Migrant Domestic Workers?’, in Ryan B (ed.), Labour Migration in Hard Times (The Institute of Employment Rights 2013), 141-156.

McColgan A., ‘Reconfiguring Discrimination Law’ (2007) Public Law, 74-94.

Sen A., ‘Elements of a Theory of Human Rights’ (2004), Vol. 32, No. 4 Philosophy & Public Affairs, 315-356.

Endnotes

[1] V Mantouvalou ‘Human Rights for Precarious Workers: The Legislative Precariousness of Domestic Labour’ (2012), 34 CLL&PJ, 2.

[2] Ibid 3.

[3] Ibid.

[4] V Mantouvalou, ‘The Many Faces of Slavery: The Example of Domestic Work’, (2012) 14(2) GD, 2.

[5] S Fredman, Discrimination Law (OUP 2011), 232ff.

[6] Mantouvalou (n1) 19.

[7] Mantouvalou (n4) 5.

[8] Siliadin v France App no 73316/01 (ECHR, Judgment of 26 July 2005).

[9] ILO Forced Labour Convention (1930), in Siliadin v France, para 115.

[10] Mantouvalou (n4).

[11] Siliadin (n8) Para 122-124.

[12] Recommendations 1523(2001); 1663(2004).

[13] Siliadin (n8) para 49(b) and (c).

[14] J O Davidson, ‘New slavery, old binaries: human trafficking and the borders of “freedom” ‘(2010) 10(2) GN, 246.

[15] E.g., Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948, Art.4; International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, Art.8.

[16] H Collins, ‘Is There a Human Right to Work?’, in V Mantouvalou (Ed.) The Right to Work: Legal and Philosophical Perspectives(Hart 2014), 28ff.

[17] Ibid 33.

[18] Kalayaan, Slavery by another name: the tied migrant domestic worker visa Report available <http://www.kalayaan.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Slavery-by-a-new-name-Briefing-7.5.13.pdf> accessed 23 April 2015.

[19] V Mantouvalou, ‘Are Labour Rights Human Rights?’ (2012) 3 ELLJ, 164.

[20] — , ‘The Right to Non-Exploitative Work’, in Mantouvalou (n16).

[21] E.g., ILO Convention on Domestic Workers No 189 (2011), Preamble.

[22] Mantouvalou (n2).

[23] A Sen, ‘Elements of a Theory of Human Rights’ (2004), 32(4) P&PA, 332.

[24] Mantouvalou (n1) 21.

[25] Ibid.

[26] E Albin, Sectoral Disadvantage: The Case of Workers in the British Hospitality Sector’ in Mantouvalou (n19).

[27] V Mantouvalou, ‘What is to Be Done for Migrant Domestic Workers?’, in B Ryan (ed.) Labour Migration in Hard Times (IER 2013), 4.

[28] S Fredman, ‘The Role of Equality and Non-Discrimination Laws in Women’s Economic Participation, Formal and Informal’ Report, (UN OHRCHR 2013), 13.

[29] Mantouvalou (n1) 4.

[30] — (n7) 2.

[31] ILO, Report Domestic Workers Around the World (2013), <http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_173363.pdf> accessed 23 April 2015.

[32] N Lacey, ‘Feminist Legal Theories and the Rights of Women’ in K Knop (ed.) Gender and Human Rights (OUP 2004), 13ff.

[33] Mantouvalou (n1) 4.

[34] A Goldin, ‘Labour Subordination and the Subjective Weakening of Labour Law’, in G Davidov; B Langille (Eds.) Boundaries and Frontiers of Labour Law Goals and Means in the Regulation of Work (Hart 2006), 122.

[35] Mantouvalou (n27) 3.

[36] B Anderson, ‘Just Another Job? The Commodification of Domestic Labour’, in B Ehrenreich, AR Hochschild (Eds.) Global Woman: Nannies, Maids and Sex Workers in the New Economy (Granta 2003).

[37] Fredman (n28) 13.

[38] Mantouvalou (n1) 5.

[39] A McColgan, ‘Reconfiguring Discrimination Law’ (2007) PL, 83.

[40] Davidson (n14).

[41] Fredman (n28) 60.

[42] Mantouvalou (n1) 19.

[43] Ibid.

[44] V Mantouvalou, ‘Life After Work: Privacy and Dismissal’ LSE Law, Society and Economy Working Papers 5/2008 <http://ssrn.com/abstract=1111957> accessed 24 April 2015.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Goldin (n34) 119.

[47] The Working Time Regulations 1998, S19; Health and Safety at Work Act 1994, S51.

[48] Mantouvalou (n1) 5.

[49] UK Minimum Wage Regulation 1999.

[50] Mantouvalou (n1) 7.

[51] B Anderson, ‘Migration, immigration controls and the fashioning of precarious workers’ (2010) 24(2) WES, 303.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Hounga v Allen & Anor [2014] UKSC 47.

[54] A Bogg and V Mantouvalou, ‘Illegality, Human Rights and Employment: A Watershed Moment for the United Kingdom Supreme Court?’ UKCL Blog (13th March 2014) available at <http://ukconstitutionallaw.org/> accessed 23 April 2015.

[55] Coroners Act 2009, S71 and Modern Slavery Bill 2015.

[56] Mantouvalou (n1) 4ff.

[57] Fredman (n28) 74.

[58] Mantouvalou (n27) 2.

Written by: Carolina Yoko Furusho

Written at: University College London

Written for: Virginia Mantouvalou

Date written: April 2015

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Capitalism and the Rise of New Slavery: From Slave Trade to Slave in Trade

- Do Colonialism and Slavery Belong to the Past? The Racial Politics of COVID-19

- Turning Domestic into Political: The Case of Female Self-immolation in Iran

- CPEC: An Assessment of Its Socio-economic Impact on Pakistan

- Intermestic Realism: Domestic Considerations in International Relations

- The Islamic State’s Guidelines on Sexual Slavery: the Case of the Yazidis