Dhee is the story of a lesbian woman in Bangladesh, who charts out her life for readers to understand gender and sexuality politics. This eponymous publication is the first homosexual narrative ever published in a graphic comic format (presented in flashcards) in Bangladesh, released in September 2015. Dhee has come out to talk about diverse sexualities, and her strategy is both personal and political. This article explains certain philosophies and themes that have gone behind the making of Dhee, and also takes on some of the questions that Dhee raises about sexuality politics.

“I have felt different since childhood. Mother would always scold me to keep my hair tidy, to do the household chores or to play with dolls. But all I wanted to do was to go out and feel the wind in my hair.”

Dhee comes with a visionary feminist take to disrupt and revise the existing incipient male-dominated LGB activism scene in Bangladesh. Dhee is a lesbian woman, not a gay man, and she presents the complexities of a woman, who not only has to wade through a male-dominated society to find a footing, but also has to negate her queer sexuality in a heteronormative masculinist space of the Bengali society. Dhee is a production of Boys of Bangladesh (BOB), which is an organization predominantly by and for gay men. The comic strip is an advocacy tool of Project Dhee, a 14-month project funded by the US Department of State with three main components: the comic, a five-year strategy, and an action plan. The double bind that Dhee faces is crafted to not only make a political statement by saying that female members of the community can have sexual urges, and be queer too, but also by creating a critical space for the male gay members of society to look at their own privileges as men, and understand their own complicities in creating dominant narratives in the LGBT scene. Dhee breaks into that culture and shows the importance of relocating other narratives for a much more nuanced understanding of how we arrive at the places where we arrive. She makes us think about who gets to speak and who is spoken about. These are critical questions that can no longer be ignored, especially in feminist discourses where hegemonic and dominant narratives can exclude other voices.

Sexuality is still a sensitive topic to address in the larger socio-cultural sphere in Bangladesh. In classrooms, sexuality is not addressed. There is no formal sex education in the Bangladeshi classroom, and aspects of sex and sexuality are not generally discussed. If and when sex is addressed, it is within the context of Biology classes, very briefly mentioned, and only in terms of using protection and the dangers of STDs. In the context of development work, sexuality is addressed in the framework of reproductive health and services.

It is more than urgent for sexuality politics to be talked about in the political framework of agency, pleasure, and power to address the unjust relations and sexual violence among community members in Bangladesh. However, there is no longer a ‘complete’ silence around LGBT issues. The government recognized Hijra as the third gender in the country in 2013[1]. In August 2013, Dhaka Tribune, the latest English Daily in Bangladesh, called for the decriminalizing of same-sex relationships in its editorial (Dhaka Tribune: 2013). However, in September 2013, the government denied education on sexuality and refused to ensure gay rights in Bangladesh, against the UN recommendation, at the Sixth Asian and Pacific Population Conference. In January 2014, Roopbaan (Beautiful), the first ever LGBT magazine in Bengali got published in Bangladesh. There are now discussions and debates about same-sex sexuality on online forums and in social networks, especially after same-sex marriage was legalized in the US in 2015.

In an essay, Bangladeshi anthropologist Adnan Hossain wrote that “[c]ontemporary Bangladesh presents a rather paradoxical situation in terms of non-normative gender and sexualities” (Hossain 2009: 20). Hossain brings in the intersectionality of class, gender and sexuality to give an idea of what homosexuality could possibly mean in Bangladesh. “Hijra a cultic sub-culture of lower class non normative ‘males’ with extensive community rules and rituals is publicly institutionalized. […] In Bangladesh ‘transgenderism’ is not conflated with any form of homoeroticism in the popular imaginary. […] Gay groups emerged in Bangladesh from 2000 onwards among the middle/upper class males” (2009: 20-21). Hossain then explains that there is no Bengali word for ‘straight’ and that there is a lack of public discourse on homosexuality, and also that overarching heterosexuality “never allowed non-normative desire to rise to the status of a legitimate sexuality. Therefore fear of same sex desire or ‘homophobia’ could not gain adequate conceptual depth” (2009: 22). He writes that it is relatively easy for men from lower socio-economic status to obtain relative freedom and agency when it comes to their non-normative gender and sexuality expression, compared to men from upper socio-economic classes. Men in the middle/upper class grow up with a “‘classed social responsibility’ that they find difficult to disrupt” (2009: 22).

Dhee’s flashcards are now used as advocacy material in workshops to start dialogues around gender and sexuality in all the divisions in Bangladesh. Participants in the workshops are development practitioners, activists, researchers who work in areas of gender and sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), journalists and students. Through the advocacy workshops, Dhee aims to create spaces for knowledge production in an engaging, non-hierarchical way, where participants can reach understandings of sexuality through the sharing and understanding of personal narratives. Dhee does not aim to lecture on sexuality, but instead insists on sharing her own narrative, and invite others to share their own, attempting to queer everyone’s understanding of identity— to change the way we look at others and ourselves. By sharing her narrative, from childhood through adolescence, to her adulthood, Dhee highlights the importance of sharing personal narratives and situated knowledges. Race theorist bell hooks in Teaching to transgress, writes, “Personal testimony, personal experience, is such fertile ground for the production of liberatory feminist theory because it usually forms the base of our theory making […] when our lived experience of theorizing is fundamentally linked to processes of self-recovery, of collective liberation, no gap exists between theory and practice” (hooks 1994: 61-70). Personal stories enhance our capacity to know and connect, for which Dhee shares her moments of vulnerabilities, joy and agency, as she explores and expresses herself.

“And then one day, just like that, love happened. I felt real love! Thousands of colorful butterflies began fluttering around me. Breath fell short. I finally realized how heavenly it is to be in love. Those were the best days of my life!”

Dhee does not aim to represent, but to speak from, a specific position in society. Elements of Dhee’s story can be familiar for others, as Dhee invites readers to read her story in mediation with their own. Readers can connect to them from their own situated positions in society. Tony Adams and Holman Jones, in “Telling Stories: Reflexivity, Queer Theory, and Autoethnography”, wrote:

My experience—our experience—could be and could reframe your experience. My experience—our experience—could politicize your experience and could motivate and mobilize you, and us, to action. My experience—our experience— could inspire you to return to your own stories, asking again and again what they tell and what they leave out. (2011: 110)

Dhee highlights that sharing personal narratives is a political act. Personal narratives, or situated knowledges, which have been subjugated or ‘straightened’ by normative spaces we grow up in, can have insurrectionary affects that motivate others into thinking and acting. They can create queer affects, chart out alternate routes of desires and life paths that are not straight, linear or normative.

However, being the first ever (homosexual) lesbian narrative in Bangladesh, Dhee may also pose the risk of being read as the definitive homosexual narrative. Such a determinant counters the project of proliferating narratives to nuance our understanding of realities. The way the workshops are pedagogically designed, to encourage other narratives to emerge, highlights the importance of a defracted[2] reading of narratives, and the implication of such an action in queer spaces.

Queer affects can be disruptive, and can affect us into thinking, questioning and taking action. Through Dhee’s transitions, we get to see how Dhee had to fit in the normative society as a young adult, and shows how the space she grows up in can comport and be oppressive. Dhee does not only ‘add’ knowledge about diverse sexualities, but she also successfully points out that the ‘normal’ or the normative space is also problematic, and should be the entrance point to critique. By sharing her personal narrative, Dhee disrupts the heterosexual landscape, and takes that as an entrance point to critique and explain sexualities. Queer theorist Kevin Kumashiro in his essay “Toward a Theory of Anti-Oppressive Education”, wrote, “Otherness is known only by inference and often in contrast to the norm and is therefore only partial. Such partial knowledge often leads to misconceptions […] Learning about and hearing the Other should be done not to fill a gap in knowledge (as if ignorance about the Other were the only problem), but to disrupt the knowledge that is already there […] changing oppression requires disruptive knowledge not simple more knowledge” (Kumashiro 2000: 31-34). The rhetoric of tolerance and acceptance is not enough to address sexuality politics, and oppression around it. Dhee politicizes our understanding of sexuality when she problematizes and draws out the limitations of the normal.

The content of Dhee is in Bengali, which is an attempt to step out of the English discourse of sexuality. There is ample resource on sexuality in English, however much less in the Bengali language. Moreover, to address the larger realities of Bangladesh, and to reach mass readership, it only made sense to develop the content in Bengali. hooks in Feminism is for Everybody, wrote, “We have not produced a body of visionary feminist theory written in an accessible language or shared through oral communication. Today in academic circles much of the most celebrated feminist theory is written in a sophisticated jargon that only the well-educated can read. Mass-based feminist education for critical consciousness is needed” (hooks 2000: 112). Such a philosophy aligns with both the use of Bengali language and the medium of illustrations and flashcards. Not only have we, content developers, tried avoiding the usage of academic language to talk about gender and sexuality, but we have also used Bengali to reach readers who either do not read in English, or do not understand English. The use of illustrations is also an attempt to break away from the culture of academic writing. The images, dialogue and information on the back of each flashcard, are meant to engage readers of all ages. hooks wrote:

Most feminist thinkers/ theorists do their work in the elite setting of the university. For the most part we do no write children’s books, teach in grade schools, or sustain a powerful lobby which has a constructive impact on what is taught in the public school. I began to write books for children precisely because I wanted to be part of a feminist movement making feminist thought available for everyone (hooks 2000: 113).

The comic format is designed to appeal to adolescents and young adults, who usually do not have a healthy and positive platforms to know about identity and sexual orientations in Bangladesh. The flashcards thus will assist young readers to engage in thoughts and discussions with peers as well. The flashcards can also be used in workshops to start dialogues. Capturing the attention of people of different ages, and doing advocacy through visual storytelling, can be effective for humane communication and connection.

Due to the hegemonic nature of the western queer movement and discourse that influences LGBT movement all across the world, it is also important to step back and to understand the complicities of the western queer liberationist paradigm that creates norms around queerness as well. The theme of ‘coming out’ as a western, individualistic expression of one’s self-expression, which is regarded as a barometer of one’s degree of liberation, is also present in Dhee. One of the flashcards explains the concept of coming out, and shows Dhee’s dilemma if she should come out to her family or not. Regarding coming out, DarkMatter, a queer South Asian artist and activist collective, wrote in their essay The US is So Behind The Times:

Many queer folks in Palestine are not actually invested in ‘coming out’ or being ‘visible.’ Movement emphasis does not prioritise the ritual of ‘coming out’ and does not pressure Palestinians to ‘come out’ in order to be involved with movement work. People are critical of the idea that there even is a ‘closet’ let alone how the West associates being a ‘bad’ queer with being closeted (repressed) and a ‘good’ queer with being out (liberated?). What is more, coming out narratives rely on the personal choices of individuals — a framework that largely does not make sense for Palestinians who may see themselves as part of a larger family and community structure.

As a content developer, I found myself wondering about this, and the implications that coming out may have in a communal society in Bangladesh. Should Dhee have critiqued coming out as well, especially in the Bangladeshi context, where coming out is an alien concept? Moreover, what could visibility and individualism mean in the current world where there is so much flux— borders are being negotiated, re-affirmed, to stop floating bodies from spilling in; terrorist suicide bombings that dissipate the divide between self and other. How can we embrace and benefit from the concept of queer as fluidity and unknowability, as opposed to individualistic and exceptional visibility? How could Dhee have elaborated more on fluidity, rather than fixedness, to explain the ever changing landscapes of gender, body, sex, sexuality, race, nationalism, etc., which are otherwise consecrated into fixed and stable categories?

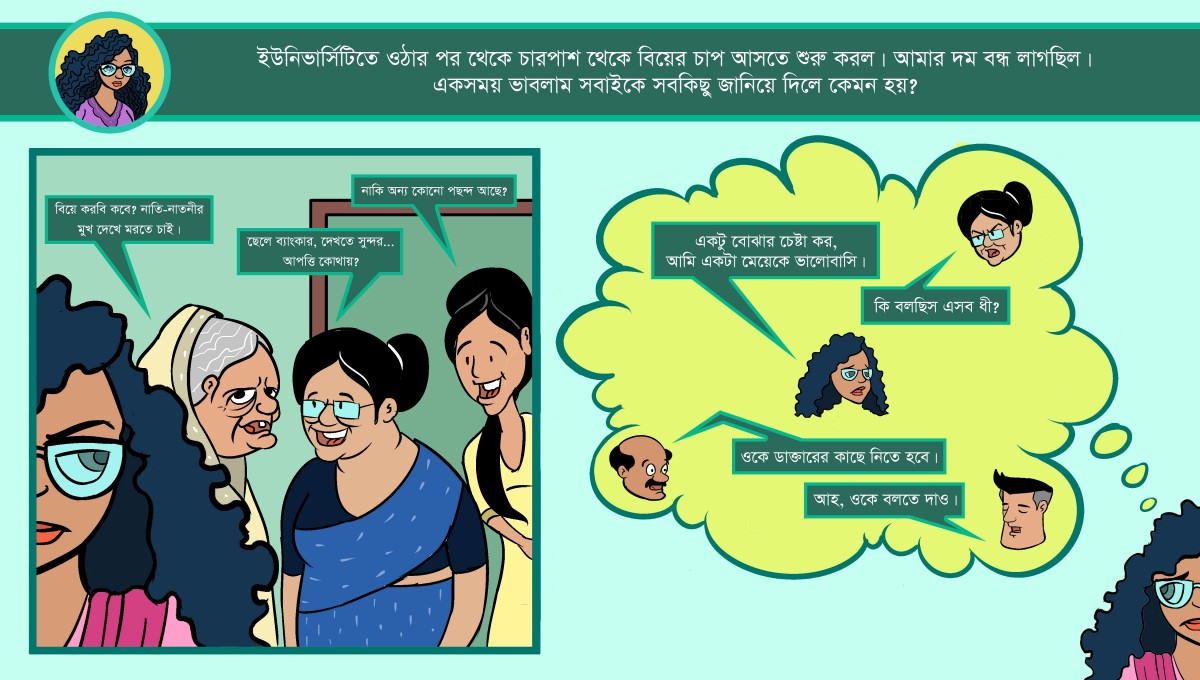

Top: “After I got into university, pressure to get married began mounting. I felt suffocated. I thought about telling the truth to everyone.” Left: “The potential groom is a banker, handsome, so what is the problem?” (mother in blue sari) / “I want to see the faces of my grandchildren before I die” (grandmother) / “Do you have anyone that you like?” (friend dressed in yellow) Right: “I love a girl and would like for everyone to try and understand me” (Dhee) / “What are you saying Dhee?” (mother) / “Dhee should be taken to a doctor” (Father) / “Let her speak!” (brother)

Queer theorist Jasbir Puar, in Terrorist Assemblages, thought of “queerness as not an identity nor an anti-identity, but an assemblage that is spatially and temporally contingent” (2007: 204). In contrast, for DarkMatter “‘Queer’ can be a radical challenge to sexual and gender oppression, but only in localised contexts, not as a globalising construct”. The concept of queer has been embraced by the LGBT community to express and establish identities. However, can queer be a mode of thinking, of conducting and of living that constantly challenges norms as a mean to constantly revise? Kumashiro wrote, “[d]isruptive knowledge, in other words, is not an end in itself, but a means toward the always- shifting end/ goal of learning more” (2000: 34). Can queer be an ever transgressing-transformative-generative project, through which we can constantly think and ask what is not being said, and whose voices are being left behind? The concept of queer can equip us to challenge the fixedness of categories that can be problematic. Now that Dhee has been published, we need to ask, what else Dhee could have said. Dhee brings in many different complexities, questions and visions. Dhee is not a closure to all the questions and concerns that have been raised all these years in Bangladesh, but is more of an entrance point to finally address these questions, and to raise more in the process. The politics around sexuality are manifold, and require constant revising. Through the workshops and advocacy programs that Dhee is doing in the country, it will be necessary to see where the discussions go, perhaps with the hope that an organic shift in understanding will take place among community members. Given that no conclusions were drawn out at the end of the comic, and that it was left to readers to figure out how would Dhee’s life turn out, the unknowability can be an essential attendant theme of the project, as opposed to deterministic knowings and conclusions.

Notes

[1]Activism around hijra rights has been visible and ongoing in Bangladesh for many years now. The new government policy is supposed to give hijras the right to identify as a separate gender from the binary genders of male and female, on all official documents, including passports. However, the pathologization of hijras continues. In 2015, government officials ‘delegitimized’ a group of hijras based on their male sexual organ, once again essentializing gender identity to the sexual organ a person is born with.

[2] Diffraction is a ‘thinking technology’ used by techno-science feminists Donna Haraway and Karan Barad. Nina Lykke in Feminist Studies explains that diffraction is a concept borrowed from Physics– “from optics and, and more generally, from the science of the interference of wave motions” (Lykke 2010: 154) that both these feminists employ to suggest that it is much more productive critical figure than ‘reflection’. “If we take the optical metaphors seriously, a reflexive methodology means using the mirror as a critical tool. Haraway notes that while this can be useful, it also has limitations if you seek alternatives and want to make a difference. For using the mirror as critical tool does not bring us beyond the static logic of the same. We can look critically at the reflection in the mirror, but no new patterns emerge” (2010: 155).

References

DarkMatter, The US is So Behind The Times (accessed 12 November 2015).

DarkMatter, Thoughts on the Queer International (accessed 20 November 2015).

Adams, Tony E. and Jones, Holman Stacy (2011) “Telling Stories: Reflexivity, Queer Theory, and Autoethnography”, SAGE: Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, Volume 11 (108), pp. 108-116.

hooks, bell (1994) Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (New York: Routledge).

hooks, bell (2000) Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate politics, Cambridge: South End Press.

Hossain, Adnan (2009) “Conceiving Sexual Agency: Sexuality, rights, homophobia, class and Islam in contemporary Bangladesh”, In plainspeak, Volume 9 (2), pp. 20-25.

Kumashiro, Kevin (2000) “Toward a Theory of Anti-Oppressive Education”, Review of Educational Research, Volume 70 (1), pp. 25-53.

Lykke, Nina (2010) Feminist Studies A Guide to Intersectional Theory, Methodology and Writing (New York: Routledge).

Puar, Jasbir (2007) Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in queer times (Duke university press: Durham and London)

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Decolonising Queer Bangladesh: Neoliberalism Against LGBTQ+ Emancipation

- Sex, Tongue, and International Relations

- Opinion – The Future of the Bangladesh Awami League

- Opinion – The BNP’s Dilemma in Bangladesh’s New Political Landscape

- Queering Genocide: How Can Sexuality Be Incorporated Into Analyses Of Genocide?

- Opinion – Counter-Terrorism and Intellectual Co-Optation in Bangladesh