Perhaps it is time to admit that I have the tendency to repeat myself when it comes to European integration and EU external relations. In my view, the history of this supranational organisation is essentially a history of political compromises among member states which ultimately formed the basis on which the Brussels based institutions could flourish during the last 60 years or so. More importantly, a fairly good indicator for the quality of a compromise is usually the degree to which the parties involved dislike it and the commentators from all corners of the political spectrum discredit respective results as disappointing. For that reason, and to my own surprise, I find myself in basic agreement with Prime Minister David Cameron. He argues that the latest proposal for a new settlement of the United Kingdom within the EU constitutes a decent result that deserves to be put in front of the British people in the form of an in-or-out referendum.

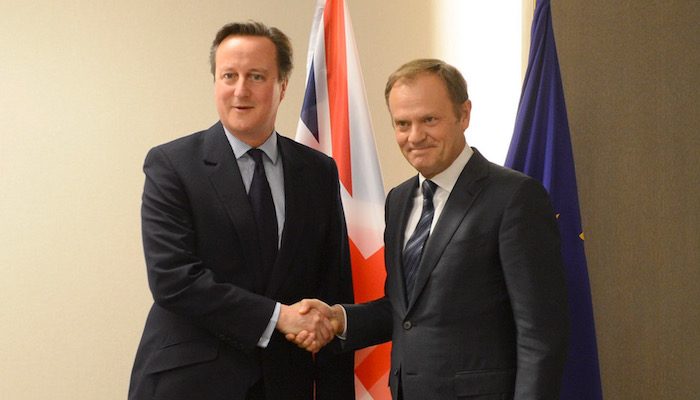

Of course ‘nothing is agreed until everything is agreed’, but, as it stands, the Draft proposal for a Council Decision (EUCO 4/16) contains a number of concessions going a long way in the direction of the concerns raised by British Eurosceptics. For the sake of further debate it is worthwhile to recall the substantive proposals that President Donald Tusk has put on the table in addressing four key areas of British discontent. Taken together, they may constitute a fundamental transformation of the current EU-UK relationship many people seem to be craving for.

As regards economic governance, the new deal guarantees to not place countries outside the Eurozone at a disadvantage; for example, by respecting their rights and competences in economic policy and allowing for different sets of rules if need be for the sake of their financial stability. In particular, there is no expectation that the UK will have to participate in the financing of further rescue efforts for the single currency despite the right to participate in all deliberations within the EU Council. The British Chancellor, George Osborne, should be very happy with such an outcome as it settles one of his deepest worries concerning the management of future monetary crises.

As far as efforts aiming to strengthen the competitiveness of the European economy as a whole are concerned, British negotiators were most likely met with open arms in Brussels. This is a goal widely shared by many fellow member states specifically in the Northern parts of Europe. It is hard to imagine that the lowering of administrative costs and regulatory burdens is something not welcomed by the liberally minded, natural European allies of the UK. Similarly, neither support for small and medium-sized enterprises, nor the fight against red tape in the form of unnecessary legislation, has been previously unheard of in established Union circles. The relatively broad support base for improved monitoring and review mechanism to ensure greater policy coherence in this area of economic policy should easily complement independent national efforts on both sides of the Channel. In fact, it might finally build up the critical mass necessary to spread the message further to the more remote parts of Southern and Eastern Europe.

On questions of national sovereignty the draft proposal speaks a very clear language as well: ‘the references to an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe do not offer a basis for extending the scope of any provision of the Treaties or of EU secondary legislation’ (EUCO 4/16, p. 9). There is no demand or expectation whatsoever that a UK government could suddenly develop a taste for further political integration. Instead, the new Council document acknowledges different paths to integration and thereby, deliberately or not, goes beyond the once popular formula of an EU journey towards an ‘unknown destination’. In the current phrasing a common destination does not even have to be the vague aspiration of all member states.

While some critics simply ignore the above as ‘Euro-speak’, the new deal has also made some considerable headway into the long-standing debate about a more meaningful implementation of the subsidiarity principle. Once seen as the saviour of the Maastricht Treaty, the governments of the member states on this occasion revived their intention to bring decision-making as closely as possible to the citizens. In their opinion, and including that of Prime Minister Cameron, an improved procedural mechanism (a red card rather than a yellow card system) should offer some true grit. If at least 16 out of the 28 parliaments in the member states continue to object to the work on a new piece of EU legislation the standard drafting process on EU-wide regulations and directives reaches a sudden death and has no chance of an easy comeback. While this may fall short of a genuine repatriation of legislative powers, it rather abruptly turns a small group of national legislatures into powerful veto players and constitutes a significant departure from the ordinary legislative procedure (OLP) of the Lisbon Treaty that had championed the European Parliament (EP) in such matters.

Last, and certainly not least, the draft proposal adds a fundamentally new interpretation to the operation of social security systems in the Union. Frequently singled out in recent weeks and months as the biggest stumbling block to a final settlement among the member states, the proposed wording merits closer scrutiny. The authors of the draft paper recognise a co-ordination rather than a harmonisation role for EU institutions when it comes to social security provisions, thus leaving room for continuing diversity in the domestic welfare regimes. The latter, however, implies an explicit recognition of regulatory failure in so far as people do not react to genuine market forces in their free movement but to the ‘false incentives’ created by more generous benefit systems. If this is indeed the case then both national and Union authorities should be allowed to introduce restrictive measures to the free movement of workers and to the extent necessary to re-establish the proper functioning of market forces.

Admittedly, it is quite an intellectual journey to deduce from this abstract reasoning in common market philosophy the real world emergency measures or safeguard mechanisms and then to apply these to the general case of welfare abuse or the specific case of in-work benefits. Nevertheless, the Tusk proposals do eventually foresee the possibility to authorise ‘a member state’ (the UK no doubt) to restrict in-work benefits for a total period of up to four years. Moreover, while such measures should most likely be the exception rather than the rule, further extensions or repeat actions are not excluded depending on the seriousness of the national crisis situation at hand.

It is fair to say that the current state of play stretches EU institutions quite far in return for the positive endorsement of the deal given by PM Cameron in the House of Commons. Remarkably, the document sorts out almost by stealth the vexed question how the proposed changes should find their way into the actual policy making process. No mention of additional protocols, white papers or further intergovernmental conferences. Rather, it is anticipated that most demands are easily accommodated via the speedy route of ordinary secondary legislation or directly incorporated into a future treaty revision.

Much more is at stake than the four themes addressed above – ultimately depending on the outcome of the forthcoming referendum: the role of the UK in global affairs, its trade relations with continental Europe, the inflow of foreign direct investment, its contribution to regional and global security and overall the type of political community it would like to be. Accordingly, one of the most outspoken critics of the deal in the House of Commons, the North East Somerset MP Jacob Rees-Mogg, doubted the negotiation skills of the PM. Later in the day, in an interview with BBC Radio Bristol, he seized the opportunity for a general polemic against the European integration project. In his account, neither Franco-German reconciliation nor the making of a global trade policy in the World Trade Organisation (WTO) had anything to do with the relative success of European integration. In his view NATO would deserve all the credit for peace in post-war Europe and British trading interests would be best served by striking bilateral agreements with other Westminster style democracies such as Canada and Australia.

In the light of such statements and blatant distortions of the truth one almost feels sorry for the more moderate voices in the Conservative party and the government ministers who came out in support of the in-campaign. The institutional and legal mechanisms around which the EU has been constructed over the years offer a rich set of procedures to de-politicise contentious issues and to find practical compromises for the member states. From trade wars to beggar-thy-neighbour policies, from migration waves to territorial demands, from aggressive business practices to blocked market access and from the use of scarce resources to competing cultural norms, the list is long around which disagreement and violent conflict may have developed in Europe. Observing many of the intergovernmental debates in the EU Foreign Affairs Council first hand, the former foreign minister of Germany, Joschka Fischer, once remarked how he could not help thinking that in a previous century governments would probably have preferred to settle the very same disagreements on the battlefield. While it is unlikely that technocratic EU trade deals with other world regions or major trading states spark a warm “we” feeling, they are one of the defining features of the global economy in the 21st century; and for that reason their contribution to genuine improvements in national welfare should not be discarded. I suppose nothing can stop the UK Independence Party’s (UKIP) Nigel Farage from claiming that an independent UK could renegotiate trade deals with the EU within days rather than weeks, although my bet in this respect would be on the expertise of Peter Mandelson. The one time EU trade commissioner suggesting a lost decade before new UK agreements would emerge similar to those between the EU and Canada or the EU and Switzerland.

Be that as it may, some real challenges for British politics are building up in the coming weeks and months with competing referendum campaigns fighting for the attention of the voters. Retrospectively, one can only look at these with a sense of irony and ask whether it has been indeed necessary to drag the membership debate into the public limelight or whether it could not have been settled within the more traditional parameters of EU politics. Remember George Soros who described the British-EU position already as ‘the best of both worlds’, a member state outside Schengen as well as outside the Euro-zone. If things go wrong, this may indeed spell the end of David Cameron as British prime minister, especially with another Scottish referendum knocking at the door. Clearly mistakes were made much earlier: caving in all too quickly to a perceived threat from UKIP and shying away from an internal debate with Eurosceptic backbenchers who try to placate their special interests with an alleged public interest in the exit option.

I am less sure though whether the PM did indeed study the intricacies of game theory before making his choices. If a new deal rather than Brexit was the prime intention, then a game of chicken is very risky indeed. This is, for example, well understood in the basic 2 x 2 version of the game around the choices of a cooperative or defective strategy by two players, i.e. two governments. It becomes, however, much harder to handle and to make any predictions when this game is played in a 1 to 27 constellation with an additional element of uncertainty due to the (theoretically neutral) mixed motives present in an overarching institutional arrangement ; in this case the administrative support structure of the Council and its Presidency. I will leave it to the mathematicians to quantify the likelihood of a welfare enhancing result for all parties involved, but praise the political instinct of Mr Cameron to change tactics halfway through the process and to re-engage with the standard European practice of bilateral diplomacy in contact with other heads of state and government and exploring the possibility to form broader coalitions with his natural allies throughout Europe.

Whether all these efforts will ultimately work remains to be seen at the ballot box. In the meantime, a rational look at the Tusk proposal leaves us not with one, but several, paradoxes at the same time. The sustained effort to accommodate all British tribulations with the EU has resulted in a slightly legalistic approach by which voters may feel tempted to react by ignoring the four key baskets and cast a vote on the basis of domestic issues and the performance of individual politicians. Despite the decent quality of the deal in its current form, the need to run a proactive and widely popular in-campaign will taint all chances to settle the EU issue within the Conservative party ‘once and for all’. On the other hand, if the no-campaign succeeds, the sovereign UK would become a rule-taker rather than a rule-maker as long as it would want to have continuing access to the single market along the lines of the Norwegian model. Finally, the quest for more independence from foreign policy coordination in Brussels may alienate important strategic partners of the UK, such as the United States and China, and subsequently weaken British positions in international politics.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Not So Bad After All: How US Foreign Policy Could Navigate a Multipolar World

- An ‘Expert’ Perspective on Brexit… Means Brexit

- Opinion – The Good, the Bad and the Ugly of COVID-19 Recovery Financing in Europe

- Is the Chagos Deal Really Under Threat?

- Brexit Never Rains, But It Pours

- The Days of May (Again): What Happens to Brexit Now?