Home-grown extremists in the UK are an emerging problem for the British Government. The pressure on the British Government to respond and combat such a threat is ever-increasing. Its policy for tackling both violent and non-violent extremism – termed to be ‘a vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values’ is attempted through a strategy called ‘Prevent.’ This is one part of a four-point counterterrorism plan referred to as ‘Contest’, which has the aim of dissuading individuals from supporting or becoming part of terrorism.

The aim of Prevent is to act decisively before the event of radicalisation. This action has two central approaches with the first focusing on the conditions that allow discontent to occur, this often includes a community based focus on promoting cohesion. This is attempted through means including counselling, education and support networks. The second is tailored to the needs of the individual, who is believed to be ‘vulnerable’ to radical ideas. A defining measurement of the need to intervene is the extent regarding whether there is an adherence to British values. This is termed as ‘including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs.’ Despite the seemingly straight forward definition; the reference to ‘British values’ can be strongly associated with patriotism. Identifying the threat before it occurs relies on the extensive channels of communication to which the public is expected to play a key role. Therefore, if there is a misinterpretation which involves viewing an absence of patriotism as opposing British values, this could accelerate divisions within local communities and mistrust of government policy.

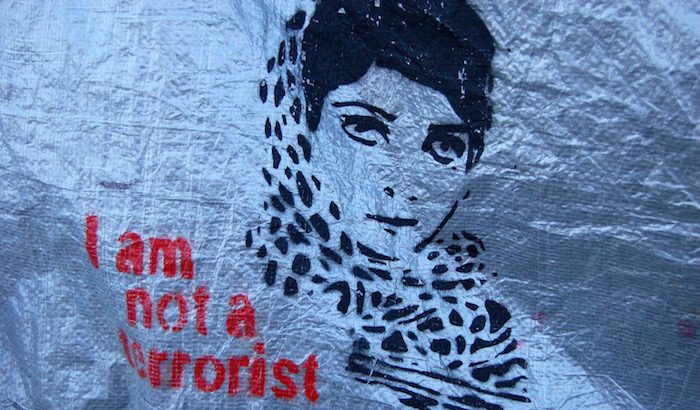

This point is further expanded upon by Rizwaan Sabir, a lecturer specialising in counter-terrorism at Liverpool John Moores University. Sabir agrees with the lack of clarity behind the definition of ‘British values’ and claims that the government is effectively outlawing dissent. This argument cites how a schoolboy had been reported to Prevent for pro-Palestinian activism. ‘The majority of Muslim parents do not believe in the supremacy of sharia [law], but if they disagree with some aspects of foreign policy, and their children pick up on that, then they could fall foul of this.’ Though the term ‘outlawing dissent’ can be considered controversial, it is worth noting that Sabir was wrongly arrested as a terror suspect while researching ‘Al Qaeda’ in 2008. He was later released without charge, demonstrating an unpleasant previous association with counterterrorism.

The theme of misinterpretations is also advocated by Mohammed Khaliel, an advisor to the Metropolitan police, who cites that due to the increased suspicions of Muslims, religious practices such a schoolgirl wearing the hijab are enough to intensify suspicion. The difficulty is that actions that can be deemed as abnormal or not demonstrating typically British behaviour, are susceptible to being reported. The need to identify a threat is powerful, while the consequences of overlooking unfamiliarity are all too evident. A repeat of the 7/7 bombings and the recent attacks in Paris and Belgium are seen as potential consequences for an absence of vigilance. This helps to understand why there is an absence of filter when it comes to suspicion. A stronger focus of Prevent on understanding and knowledge, especially concerning Islam, would be beneficial in not allowing certain communities and groups to be ostracised.

The Prevent scheme also fails to attain the necessary support from academics and students. One group of vocal critics towards Prevent are the National Union of Students (NUS). The organisation described the strategy as having ‘vague and not achievable’ expectations on universities and their staff, while reluctantly admitting that student unions would be expected to adhere to the policy. Such opposition has been organised into a mobile protest, a ‘Students not Suspects tour.’ The constant requirement to monitor and be vigilant does appear to encroach on freedom of expression, as demonstrated by the aforementioned academic opposition to the policy. The treatment of Sabir is also evidence of extreme vigilance and impulsiveness. However, given the nature of the terrorist threat, some may argue that the infringement into human rights is necessary in order to maintain national security.

It is evident with Prevent and other strategies such as ‘the interception of communications, equipment interference and the acquisition and retention of communications’ that the British state is attempting to expand its power and influence. The consequence of this is an uncertainty in defining ‘potential terrorist activity’, while such indecision increases there is more possibility of misplaced accusation and therefore mistrust of policy. The result is a society suspicious and fearful of itself and those who are meant to represent it. To change this, the Prevent strategy needs to be rectified to instead encourage cohesiveness and a better understanding of different ethnic groups – some of the core principles in any democratic society. Only when this has been achieved can those responsible for terrorist acts be pursued effectively.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Third Cinema and Social Science

- Does the Public Get What it Wants? The UK Government’s Response to Terrorism

- Why Time Matters When Proscribing Terrorist Groups

- Opinion – The Hypocrisy of the UK Government’s Plans for Girl’s Education in the Global South

- Terrorism in Africa: Explaining the Rise of Extremist Violence Against Civilians

- Contexts and Questions Around the UK’s New Protect Duty