Conflict in Phnom Penh and Capitol Hill: An Analysis of U.S. Policy Towards Cambodia Between 1969-1973

The Second World War came to a close in September 1945. Yet, armed conflict continued in Southeast Asia, with the First Indochina War fought between the League for the Independence of Vietnam (Viet Min) and French colonial forces. A Report to the National Security Council (NSC-68) on April 12, 1950, enhanced the policy of containment by presenting the developing hostilities between the United States and Soviet Union as a zero-sum game: win or lose. As a result, Southeast Asia would become a frontline in the Cold War. This was confirmed by the outbreak of the Korean War just a month later, prompting the U.S. to become entangled, both diplomatically and militarily, in the region. Cold War hostilities would eventually intensify within Vietnam and consequently the U.S. would be at war for over a decade. Throughout the Cold War and to the present day, the Vietnam experience looms in the political psyche of the American nation. This is heavily represented in popular culture by film and literature in addition to its common use as an analogy by policy-makers in discussion addressing contemporary military intervention. However, the monopoly bestowed to Vietnam vis-à-vis superpower interplay in Indochina can be questioned, less emphasis is placed on neighbouring Cambodia.

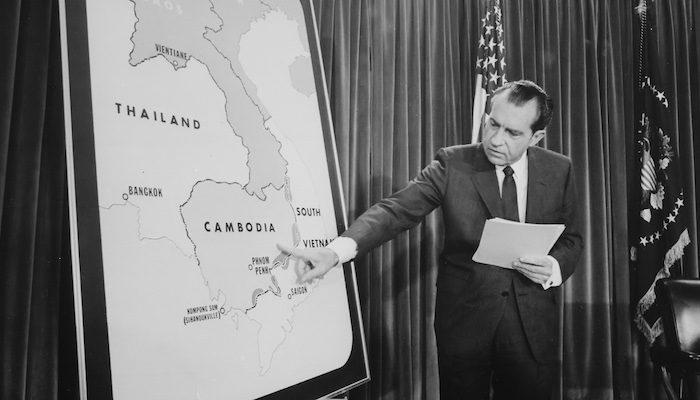

According to Clymer (2004a), the U.S. had no diplomatic or consular representation in Cambodia until 1950, which explains the severely limited U.S. interest and familiarity in Cambodian affairs. Yet, once dedicated to preventing the spread of communism in the sub-continent dubbed ‘Indochina’, the tactics of U.S. policymakers would develop beyond several national constituencies. During the peak of the Vietnam War, the Administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson escalated the American military campaign, involving the covert use of special forces teams across the Cambodian border. Although limited military action started under the Johnson Administration, resolute American involvement in Cambodia came about after the 1968 U.S. Presidential election; Richard M. Nixon was sworn in as the 37th President of the United States. Elected as a self-proclaimed “peacemaker” (Nixon, 1969), Nixon’s legacy has been documented by scholars on somewhat contrary grounds.

The presidency of Richard M. Nixon remains an area of deep interest for scholars. A significant figure within the Nixon years was Henry Kissinger; who served as Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs 1969-1975, and then Secretary of State 1973-1977. Kissinger’s influence was so great that Nixon and Kissinger are often conjointly discussed. While there is ample scholarly works on U.S. politics during the Nixon-Kissinger era, consideration for the successes and failures of their policies toward Cambodia is more limited.

This diplomatic history-based project will examine U.S. policy towards Cambodia, beginning with Nixon’s coming to office in January 1969 until the passing of the War Powers Act of 1973. This project draws on primary material so as to develop an evidence based analysis. Furthermore, the use of secondary sources has allowed the study of a deep range of distinct standpoints. At the heart of this project is the aim of examining the core strategy of the Nixon Administration towards Cambodia. The underlying objective of the the project is to advance the case that the U.S. role in Cambodia – which can often be eclipsed by the Vietnam War – warrants higher scrutiny by scholars. The project will include two chapters. Chapter One will outline the major policy paths from 1969 through to 1973. This chapter will allow for analysis of U.S. involvement in Cambodia as well as considering the impact on the target country itself. Chapter Two aims to measure the repercussions of the U.S. approach to Cambodia on policy-making in Washington. Initially, the chapter will critically reflect on the centralised style of policy-making during the period. It will also examine numerous controversies regarding the execution of Nixon’s strategy, such as the covert bombing of Cambodia under Operation Menu. It will be argued that Cambodia should be seen as a leading reason for the consequent attempts by Congress to limit presidential war powers. This chapter shows that President Nixon’s foreign policy not only had implications abroad but would also lead to permanent changes within U.S. policy-making.

CHAPTER ONE – President Nixon’s Strategy and Central Policies towards Cambodia

The Kingdom of Cambodia gained independence from French Indochina in 1953. By 1953, Cambodia, often referred to as ‘Kampuchea’ by the local populace, was led by King Norodom Sihanouk. Sooner after, Sihanouk would abdicate the throne in order to engage in party politics. Despite proclaiming neutrality, Cambodia would become an active participant in the Vietnam War. Even more so after a coup de état in 1970, during which the then Minister of Defence, Lon Nol, was installed as head of a pro-U.S. regime.

While in theory, the decision to expand U.S. involvement in Cambodia was to impact upon events in neighbouring Vietnam. The case will be made that in practise, the action taken shaped Cambodia itself, so profoundly, that this episode warrants close scrutiny. This section will analyse several policy initiatives, in order to set out the central pillars of U.S. involvement in Cambodia. Firstly, the military incursions, Operation Menu and the Invasion of Cambodia. Secondly, Operation Freedom Deal and political support to the post-Sihanouk regime in Cambodia (Lon Nol’s Khmer Republic). Throughout is the attempt to critically review these policies and reflect on the consequences of Nixon’s approach towards Cambodia.

Operation Menu and the 1970 Invasion

The Nixon Administration would look to a policy called ‘Vietnamization’: the concept that the South Vietnamese military would takeover the defence of the Republic of Vietnam (ROV) from the Americans. In the pursuit of this policy – between 1969-1975 – the U.S. would bomb Cambodia so extensively that it would account to “three times the amount dropped on Japan in the closing stages of World War II” (Chandler, 1991, p.225). The justification behind this level of violence was the mission to destroy North Vietnamese communist sanctuaries in eastern Cambodia. In 1969, a fortnight before his inauguration President-elect Nixon, in a memorandum to Henry Kissinger, demanded a “precise report on what the enemy has in Cambodia” (Nixon, 1969). He went on to express his desire that a “definite change of policy toward Cambodia [should] probably be one of the first order of business when we’re in” (Nixon, 1969). This illustrates the speedy resolve of the new administration to enhance U.S. operations in Cambodia.

Alongside this resolve, the change of presidency amended the means by which the U.S. would peruse its strategy: “The White House was now occupied by men who were prepared to take risks that Johnson had rejected and to ignore limits that he had recognized” (Shawcross, 1979, p.73). The White House’s preliminary strategy on Cambodia was to destroy enemy sanctuaries along the Ho Chi Minh trail on the border frontier, in order to undermine the North Vietnamese military campaign. It was anticipated that action would target the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), the North Vietnamese military headquarters for operations in South Vietnam. In an attempt to pinpoint the logic behind this policy, Kiernan states “As the Vietnam War ground on, the U.S. became more determined than ever to rid itself of the disadvantage it faced while Vietnamese communist troops were able to take refuge in sanctuaries just across the Kampuchean border” (2004 p.285). This quote helps to explain the relevance of Cambodia within wider U.S. strategic aims.

In the first book of his memoirs, Kissinger (1979) recalls that from day one, the president was for a more active policy towards Cambodia. In March 1969, after a conclusive meeting of the National Security Council (NSC): Nixon ordered Operation Menu, this began a prolonged period of secret bombing of Cambodia. Fittingly, it began with Operation Breakfast. Once the first mission remained unnoticed by the media, “it would now have been hard for the White House to insist on only one attack” (Shawcross, 1979, p.26). Accordingly, Operation Menu would remain secret for a year with flight records falsified. Shawcross (1979) divulges that very few senior officials were informed and that official records didn’t just conceal the raids but failed to state that they had even occurred at all. The account of Shawcross has shown the determination of the Nixon Administration to keep the expansion of U.S operations in Cambodia undisclosed. It is worth noting that one conceivable reason for this approach was the desire from the White House to publically endorse American military de-escalation within the Vietnam context. This was the central policy from which Nixon had received his mandate from the American people.

Despite the secretive approach regarding the formation of this policy, the implementation of Operation Menu was done with much more purpose. To demonstrate: “During the next fourteen months, 3,875 sorties were flown by U.S. Air Force B-52s…a total of 108,835 tons of bombs” (Morocco, 1988, p.140). Despite the grand scale of bombing illustrated by Morocco, for scholars it remains a highly contentious issue as to whether the decision to bomb Cambodia complimented U.S. foreign policy objectives. Many scholars forward the case that Operation Menu had little impact on Vietnam but that it resulted in extensive consequences for Cambodia (Morocco, 1988; Clymer, 2004; Kiernan, 2004). This suggests that the Nixon Administration misapprehended the effects of their actions.

The primary consequence can be identified as the instability brought upon the Government of Cambodia, which was led by Prince Norodom Sihanouk. The Prince – who had ruled Cambodia since independence from France in 1953 – took a neutral stance in the Vietnam War despite the threat of North Vietnamese domination and U.S. diplomatic pressure. Yet, to maintain his nation’s neutrality, Sihanouk took a laissez-affaire approach towards North Vietnamese presence along the Ho Chi Min trail and to border infringements by ROV forces. Naturally, this approach frustrated the Americans, who were keen to see the Vietnam conflict draw to a close. This helps to explain why the U.S. sought to take the issue into their own hands by bombing the eastern border. Increased violence ensued, along with hostile developments within domestic Cambodian politics which in turn damaged stability and weakened the authority of the Sihanouk government. It is worth noting that the Prince can be complimented for the use of his personal leadership and brinksmanship to avoid falling hostage to either Communist aggression or American proxy status. In spite of this, almost exactly one year after the start of Operation Menu, he was removed from power after a coup and replaced by the pro-U.S. Lon Nol.

Nonetheless, the development of pro-American leadership in Phnom Penh failed to alter Nixon’s initial approach towards Cambodia, as is demonstrated by his second major policy initiative – the 1970 invasion. On April 28, 1970, the order was given to action the invasion of Cambodia (NSDM 58, 1970). Two days later, the scope of the operation was presented to the American public in a televised Presidential address. Nixon affirmed “Tonight, American and South Vietnamese units will attack the headquarters for the entire Communist military operation in South Vietnam” (Nixon, 1970). With a strong tone of alarm, Nixon attempted to justify his decision by citing his commitment, as Commander in Chief, to protect U.S. national security and the lives of American soldiers in South Vietnam. In a direct challenge to the logic presented by Nixon, Schlesinger makes the observation that “The enemy bases and the threat to American forces had existed in Cambodia for years; there was no sudden emergency in April 1970; indeed, the enemy had already largely evacuated the sanctuary areas by the time the invasion began” (1974, p.189). After the speech, Nixon and Kissinger enjoyed a private viewing of the film Patton – a meaningful act apropos Nixon’s desire for an American victory of his own making. Moreover, as 30,000 U.S. soldiers stormed the border and proceeded to hunt enemy sanctuaries, Nixon compared his choice to invade with Kennedy’s “great decision” with regards to the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis (Schlesinger, 1974, p.189). This demonstrates an unwarranted sense of grandeur on the part of Nixon. On reflection, the association between Cambodia and earlier American triumphs is rather unhelpful due to the exclusivity of the situation in Cambodia.

It can be argued that the invasion was only of limited success, if any at all. COSVN, the flagship target of U.S. action, was not found. Kiernan claims that as a result of the invasion and increased bombing raids, “Peasants were killed – no one knows how many – and Communist logistics were somewhat disrupted” (2004, p.285). Such a poor outcome, as presented by Kiernan, raises warranted doubts over the credibility of the American strategy. At home, as the scale of anti-war protests rose across American campuses, Nixon branded the Cambodian incursion as “the most successful operation of this long and difficult war” (Nixon, 1970). In an attempt to qualify the operation’s contribution to Vietnamization, Nixon announced an accelerated withdrawal of forces from Vietnam.

In the short term, it is generally agreed that “President Nixon’s Southeast Asia policy of Vietnamization and withdrawal weathered the domestic storm caused by the Cambodian incursion” (Nalty, 2000, p.198) Clymer’s account, which argues that “The bombing had little impact on the war in Vietnam, but it had ominous consequences for, Cambodia” (2004b, p.11) be used to question the Nixon Administration’s analysis. Likewise, in response to the increased U.S. involvement and use of air power; “North Vietnamese and Viet Cong pushed their sanctuaries and supply bases deeper into the country…the war spread” (Kieran, 2004, p.286). This assessment offers support to the argument put forward in this section.

Significantly, even the account from the official U.S. Air Force History records state “the border crossings of April and May 1970 inaugurated more than a decade of foreign conflict or civil war, attended by famine, disease, and mass slaughter” (Nalty, 2000, p.195). This seeming concession from the U.S. establishes that after the invasion, war and violence spread. A resulting outcome of the increase in violence was that the U.S. would become entrenched and further beholden to support its ally, Lon Nol, thus explaining the continuation of U.S. air power in Cambodia. This relationship will be examined in the next sub-section.

Maintaining the Lon Nol regime: Military Aid and Operation Freedom Deal

One of the first associations involving Lon Nol and the U.S. was in 1964. In 1963, after Sihanouk discovered that the U.S. were covertly supporting the Khmer Serei – a republican and nationalist force – relations broke down, which resulted in the closing-down of the American military aid programme. Shawcross reports a final meeting between the then Minister of Defense, Lon Nol, and General Taber, head of the U.S. mission. During the meeting, which was expected to be merely an act of diplomatic courtesy, Lon Nol departed from the official Cambodian Government line, expressing his sadness to see the end of the U.S. mission and implied that the decision was taken by Sihanouk alone (Lon Nol cited by Shawcross 1979, p.61). On reflection, the Lon Nol-Taber meeting is significant due to the exposure of his contempt for Sihanouk. It led to the U.S. considering Lon Nol as an important potential candidate as successor to lead post-Sihanouk Cambodia. The meeting could thus be seen as the foundation of the union between the respective parties and more importantly, the origins of the ensuing Lon Nol-Nixon alliance.

In 1970, U.S.-Cambodia cooperation was something of a novelty in international relations. It is worth noting that a Pentagon report published in 1959 on the people of Cambodia stated that “their horizons were limited to village, pagoda and forest… they cannot be counted on to act in any positive way for the benefit of U.S. aims and policies” (Department of Defense, cited in Shawcross 1979, p.55). Despite this, just one decade later, in 1969, Cambodia was to be used as the next major tool in the execution of the central U.S. foreign policy in Southeast Asia: Nixon’s Vietnamization. Its most likely true that the U.S.’s general dissatisfaction towards Cambodia was still valid in 1970. However, it was hoped that a new leader could take Cambodia on a course that would be beneficial to U.S. policy.

The competence and decision-making of Lon Nol has been heavily critiqued in many scholarly works on Cambodia (Shawcross, 1979; Chandler, 1991; Nalty, 2000). Yet, it can be conceded that his defiance towards the North Vietnamese Communists was unwavering. Nalty (2000) notes that even President Nixon was fascinated by the willingness of the new government in Phnom Penh to defy Hanoi. As a result, the U.S. overlooked Lon Nol’s weak army and flawed leadership to form an alliance, which could be described as a relationship formed with the heart rather than with the head. This shows that apart from the shared dislike of North Vietnam, there was little definitive logic which supported backing Lon Nol. Accordingly – “He clung to office for four years as Cambodia collapsed around him” (Chandler, 1991, p.5).

As a direct result of the policy to ally with Lon Nol’s Khmer Republic surfaced the military campaign called Operation Freedom Deal 1970-1973. U.S. bombing was restricted to a forty-eight kilometre area: from the Mekong River to the Vietnamese border. Despite this, Morocco (1988) records that a total of 3,634 sorties, which accounts for 44% of the total number, were flown outside of the Freedom Deal boundary. This quote demonstrates a clear continuation of the improper and concealed approach established by the prior, but still ongoing, Operation Menu.

Accompanying the air mission was direct support to Lon Nol’s army and government; this was a complicated process involving U.S. military attachés and diplomatic staff from Phnom Penh, Saigon and Bangkok. The U.S. provided arms and ammunition to the remodelled Khmer National Armed Forces (FANK) which was modelled on the staff structure of the U.S. Army. In contrast to previous U.S. aid to Cambodia in the Sihanouk era, Nixon’s aid to the Khmer Republic was comprehensive and continuous in nature. To indicate the level of Nixon’s commitment to Lon Nol, between 1970-1974 the U.S. had provided “1.8 billion dollars in assistance” (Tucker, 2011, p.376).

The task of facilitating a pro-U.S. government in Phnom Penh proved to be far more gruelling for the U.S., “Hanoi responded by stepping up its backing for the indigenous Khmer Rouge Communist movement” (Morocco, 1988, p.149). Accordingly, Operation Freedom Deal which launched in 1970, would aim to defend Lon Nol’s forces against not only against the North Vietnamese but also the Cambodian Government’s domestic adversary- the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) [Often referred to as the Khmer Rouge]. It is worth noting that the CPK was an underground organisation, since it highlights the complexity of Cambodian politics during the period. In order to gain wider support from Cambodians, the CPK operated under the emblematic banner of the Royal Government of the National Union of Kampuchea (GRUNK).

“North Vietnam and the Cambodian Communist insurgents, at last with a common enemy, formed an alliance for the first time against the latest US proxy, the government of Lon Nol” (Haas, 1991, p.16-17). This quote shows that the U.S. were now engaged with the enemy on multiple fronts. The use of U.S. air power was initially enacted to defeat the North Vietnamese. However, in order the maintain the pro-U.S. Khmer Republic, bombs would now be targeting the home-grown anti-Lon Nol CPK-led forces. Indeed, after Operation Menu and Operation Freedom Deal, Chandler claims that the principle effect of these actions “was to push main force Vietnamese Communist units deeper into Cambodia, where they soon began to take apart Lon Nol’s poorly trained forces” (1991, p.204). This action therefore prompted a full-scale ground war with the North Vietnamese and Vietcong forces inflicting heavy causalities on FANK, which directly threatened the survival of the Khmer Republic.

The case can be made that an additional consequence of U.S. policy was the emergence of Civil War in Cambodia. “In the Sihanouk era, few Cambodians were willing to desert their fields to engage in rebellion or other political activity” (Chandler, 1991, p.4). By 1969, Chandler’s description of Cambodians as an obedient creed was no longer relevant. The escalation of U.S. operations in 1969 had induced a sense of general militancy and rebellion. The increased violence and killing in Cambodia amplified support for the Khmer Communists, who were using anti-U.S. rhetoric to exploit the sway of Khmer nationalism. In time, U.S. policy funded and maintained a fragile regime against the Cambodian Communists – a resilient enemy that had made gains from the home-grown support after earlier and on-going U.S. bombing. This points to the further unforeseen consequences of Nixon’s approach to Cambodia.

After two years in power, despite thousands of U.S. bombing raids in support of his forces, Lon Nol and FANK were losing ground. In 1972, in a letter to President Nixon, as well as expressing his gratitude for the President’s “unconditional and very active support”, Lon Nol wrote that “we will need a new contingent for some thousand additional weapons” (Lon Nol, 1972). Despite receiving “almost exactly one million dollars per day” (Kiernan, 2004, p.413) in U.S. aid, the Lon Nol regime was deteriorating rapidly. Shawcross (1979) reveals that FANK field commanders were operating almost autonomously from the control of the national government, even selling U.S. supplies to the enemy to enhance their private assets. Therefore, at times, the Lon Nol–Nixon arrangement failed to benefit either party. The clear absence of leadership and strategic astuteness on the part of Lon Nol suggest major misgivings at the heart of Nixon’s strategy of sponsorship and patronage for the Cambodian leader.

One major and evident weakness of Nixon’s approach to Cambodia was its dependence on Cambodian-South Vietnamese-Thai cooperation. While Lon Nol, in short, wanted U.S. aid, the U.S. naively bid to assign South Vietnam and Thailand to the defence of their fellow pro-U.S. neighbour, the Khmer Republic. While these nations were united in opposition against North Vietnamese aggression, there is value in disclosing the conflictual hostility between the three states which goes back to wars between the early empires of Angkor, Siam and the Anamities. Such tension was even conceded by a U.S. official during a meeting of the Washington Special Action Group (WSAG) in 1970. Thomas Karamessines, Deputy Director of the CIA admitted “Both the South Vietnamese and Thai [governments] are looking for border adjustments at Cambodia’s expense” (Karamessines, 1970). This was largely ignored by the Nixon Administration, which was adamant on increasing the use of foreign troops in place of U.S. troops, in addition to the use of ROV pilots and soldiers supporting U.S. operations in Cambodia. This example demonstrates that the policy stance of the U.S. towards Cambodia was crippled with a lack of awareness of regional sensitivities and recent bilateral relations.

The general mistrust between the three nations – Khmer Republic, Thailand and ROV – would have an adverse effect on U.S. strategy. This is qualified by Nalty (2000), who states that Cambodian front-line officers mistrusted ROV pilots. As a result of this mistrust, U.S. forward air controllers directed air strikes in Cambodia in place of ROV personnel. Consequently, a disproportionate number of air strikes would be directed by the U.S. military at a time when the American role was meant to be lessening; this was due to Congressional acts which will be discussed in the next section. Nalty also conveys scepticism towards Nixon’s plan to involve the Thai military in support of Lon Nol’s Khmer Republic when he claims – “Toward Thailand, Cambodians felt suspicion… for Thai rulers had once controlled the western portions of the Khmer Republic” (2000, p.278). Aside from the general distrust between the cited nations and peoples of Southeast Asia, the negative rapport between Cambodians and Vietnamese would prove to be the most serious complication and source of trouble for the U.S. strategy.

Cambodians were generally hostile towards the Vietnamese “whether from the South or the North” (Nalty, 2000, p.278). This lack of distinction proved unhelpful for U.S. policy which relied on Cambodians fighting with ROV forces against the North Vietnamese communists. Aside from territorial disputes over the area known as Kampuchea Krom in Southern Vietnam, racial tensions had flared up after an increase in anti-Vietnamese protests. This even led to the murder of ethnic Vietnamese villagers in Cambodian towns, particularly ones which had been heavily bombed by Saigon. Thus in return, ROV pilots therefore had little concern about bombing Cambodian civilians, indeed Shawcross (1979) even reveals that airman were paying bribes in order to be permitted to go out seven days a week over Cambodia. Commenting on the conduct of ROV forces operating alongside the U.S. in Cambodia, Shawcross wrote “Cambodia was open house for the South Vietnamese Air [Force]… they behaved as if they were conquering a hostile nation, rather than helping a new ally” (1979, p.174-5). As a consequence, rising civilian causalities and the inaccuracy of aerial bombardments played into the hand of Khmer nationalism and the recruitment of the CPK. Ironically, the Americans were financing the anti-communist South Vietnamese to carry out operations. This ultimately benefited the communist Cambodian insurgency which was originally allied to North Vietnam. This further demonstrates the ill-judged and short-term outlook of Nixon’s decision to expand the Vietnam War into Cambodia.

Like the Khmer Republic itself, which surrendered to the CPK leadership on April 16, 1975, Operation Freedom Deal had a prolonged demise. Nixon’s strategy for Cambodia was damaged after the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin resolution was repealed and the Cooper-Church amendment passed; measures taken by Congress on Cambodia will be discussed in full in the next section. In 1973, as fighting between FANK and forces loyal to the CPK/GRUNK alliance intensified, a cease-fire was declared after the Paris Peace Accords was signed on January, 28th. Yet, from February, the bombing campaign continued in an attempt to target CPK forces. Congressional opposition, although persistent, did not thwart Nixon’s continuing covert air support and aid to Lon Nol; “U.S. Air Force tactical fighter bombers were soon operating in direct support of beleaguered Cambodian forces on the ground, although such strikes were officially denied by the U.S. government” (Morocco, 1988 p.146).

After the Paris Peace Accords, the suspension of bombing in Vietnam and Laos meant that the U.S. Air Force was concentrating solely on the Cambodian campaign, with strikes illegally directed straight from the U.S. embassy in Phnom Penh. At this point in the conflict, scholars including Owen and Kiernan (2006) state that Cambodia stands as the most bombed country in history. Secondary consequences after the surge of bombing, included the thousands of new casualties and disruption of agriculture, leading to famine and to people fleeing into the overcrowded capital city, Phnom Penh. Arguably, this created the conditions and chaos that heightened the difficulties of the government of the Khmer Republic, at a time when it was engaged in a fierce campaign against the CPK. In hindsight, the case can be made that the role of the U.S. increased the likelihood of a victory for the CPK and the beginning of the Democratic Kampuchea regime led by the now-notorious leader, Pol Pot.

In short, Nixon’s policy of supporting the Khmer Republic was undermined by Hanoi’s response in aiding Lon Nol’s adversaries. After 1973, CPK forces got stronger and more organised, thus becoming more independent from North Vietnamese supervision. This was partly due to funding from Hanoi’s geopolitical foe during this period: China. This was where Sihanouk resided in exile as the reluctant puppet figurehead of GRUNK, where he had no power over what happening on the ground. On reflection, the association with Sihanouk increased support for the communists, as, “nationalism, not just Communism drove the movement now” (Shawcross, 1979, p.281). As the North Vietnamese lost their supervisory role of the CPK, the U.S. were engaging in a frenzied bombing campaign, in between, two warring Cambodian factions in a situation which itself had been crafted by previous U.S. action. On September 21, 1972, it was two years into the Cambodian Civil War, the Pentagon announced an important milestone – it was the first week since 1965 that a week had passed without the death of an American solider in Vietnam. Yet, within the Cambodian ‘civil war’ were the footprints of a wider proxy vendetta between Washington and Hanoi: a conflict designed to buy time for Kissinger to rescue the prestige of his nation at the negotiating table in Paris (Morocco, 1988).

The expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia was designed to help the position of Saigon Government in the conflict with the North Vietnamese. In contrast, it benefitted their adversaries in Hanoi much more significantly. It’s architect Nixon, elected to reduce American involvement and to bring the Vietnam conflict draw to a close. Vietnamization was the intellect behind a “show of force intended to prod Hanoi into accepting American terms for a negotiated settlement of the War” (Morocco, 1988, p.149). Arguably, however, Vietnamization was a false premise. It had little outcome on Vietnam but came at a high price for the people of Cambodia. By mid 1970 – after a year of intense covert bombing – the U.S increased its involvement in Cambodia following the proclamation of the Khmer Republic.

The U.S. had taken to a dubious leader: Lon Nol. Despite receiving “almost exactly one million dollars per day” in U.S. military and economic aid (Kiernan, 2004, p.413), years later Lon Nol’s Cambodia was in a worse position than at its beginning in 1970. In one of his last pieces of correspondence in the White House, in 1974, Nixon wrote privately to Lon Nol stating “I am convinced that under your vigorous leadership and that of your government, the republic will succeed” (Nixon, cited by Shawcross 1979, p.325). In contrast with this outlook, even the official U.S. Air Force account concedes – “The Khmer Republic seemed leaderless” (Nalty, 2000, p.410).

This section has maintained that Operation Menu and Operation Freedom Deal both contributed to a proxy war between Lon Nol backed by the U.S. against Pol Pot’s forces. In 1973, the U.S. had withdrawn from its combat role in Vietnam after the Paris Peace Accords. Yet despite Nixon’s notorious claim that he had achieved “peace with honor in Vietnam and in Southeast Asia” (Nixon, 1973), it did not take long for full-scale war to ensue in both Vietnam and Cambodia. By the end of April 1975, both Saigon and Phnom Penh were under communist control.

CHAPTER TWO – The Domestic Predicament: Implications for Presidential War Powers

After nearly two decades of armed conflict, Saigon fell to North Vietnamese forces on April 30, 1975. As Vietnam began its transition to unification, the United States was in political and social upheaval. Just one-year prior, after numerous criminal deeds characterised as the ‘Watergate’ scandal, President Richard M. Nixon had left the White House: the first time a serving U.S. President was to resign in disgrace. Still, the purpose of this chapter is not to address the overall legality of U.S. government and politics during the Nixon years. Rather, it is to analyse the conduct of the Nixon Administration vis-à-vis policy-making towards Cambodia.

This chapter will examine U.S. policy-making towards Cambodia between 1969-1973; in addition, it will show that Nixon’s policies led to tensions within the U.S. Government. The second sub-section focuses primarily on efforts by Congress to limit war powers of the President. In sum, this chapter proposes that the main repercussion of the U.S. approach towards Cambodia was changes to policy-making in Washington. Furthermore, that the domestic storm caused by Nixon’s provocative approach to Cambodia led to a constitutional contest between the White House and the U.S. Congress. In due time, this would overwhelm Nixon’s approach to Cambodia and contribute to his political demise.

Centralised policy-making under Nixon and Kissinger

At the onset of the Nixon Administration, Henry Kissinger reworked the National Security Council (NSC) system and revised it to serve the needs of the new president. The NSC was born from the 1947 National Security Act, which was signed by President Harry S. Truman. It was formed to provide the U.S. Government with a principal forum for national security and foreign policy matters in response to Cold War hostilities. Suri notes that President John F. Kennedy had begun the process of converting the NSC from an “administrative organ” to a “policy-making body” (2007, p.205). Further changes to the policy-making system, in particular reforms to the NSC, went hand in hand with Nixon’s policy approach in Southeast Asia: “…[Nixon] and Henry [Kissinger] saw it as a vital first step in extricating the United States from Vietnam” (Dallek, 2007, p.85). By using the NSC as their “personal creature” (Suri, 2007, p.205), Nixon and Kissinger were able to craft a system which “indisputably aimed at enlarged Presidential control over foreign policy” (Dallek, 2007, p.8). In a memorandum from Kissinger to President-elect Nixon on December 27, 1968, Kissinger set out his proposal for a new NSC system. Kissinger critiqued the NSC structure under previous U.S. administrations, claiming that “in recent years the NSC has not been used as a decision-making instrument”, adding that a new structure would provide the president with the “recommendations of all interested agencies” (Kissinger, 1968). Yet in practise, ironically, under Kissinger’s management the role of the NSC in foreign policy coordination and involvement of other government agencies was severely reduced.

Throughout Nixon’s Presidency, within the executive branch, there was a severe lack of genuine consensus over U.S. policy towards Cambodia. Yet, this seeming constraint failed to alter the decisive style of Nixon’s foreign policy. It is imperative to examine relations within the Nixon Administration in addition to pinpointing the key tools at the disposal of the White House. In particular, the handling of the foreign policy bureaucracy. A meeting of the NSC on April 22, 1970 can be examined. During the meeting, held prior to the invasion of Cambodia, senior members of the NSC advised that American involvement should be limited to air support. This was to Nixon’s displeasure. Due to President Nixon’s insistence that “there should be no note taker” (Nixon, 1970), there is no official record of the meeting. However, Siniver (2008) relying on secondary accounts, reveals that many of those present argued that a U.S. invasion of Cambodia would yield no benefits to the administration or to the overall war effort. This indicates the unpopularity of the decision to invade Cambodia, even within the higher circles of the Nixon Administration. Yet it is clear that achieving consensus on operations in Cambodia between senior members of the U.S. Government was not a priority for President Nixon.

Moreover, difficulties were still found – even with those who backed Nixon’s position. In his memoirs, Kissinger recalls that Vice-President Spiro Agnew made the case for strong U.S. involvement, even explicitly expressing that there shouldn’t be any “pussyfooting about” (1979, p.490). This infuriated Nixon, who was eager to be “the strong man of the meeting” (Kissinger, 1979, p.499). In an attempt to lessen further acts of dissent from senior U.S. Government officials. the new Washington Special Action Group (WSAG) would be given an enhanced role within policy-making towards Cambodia. Four days after the NSC meeting of April 22, Nixon ordered the invasion of Cambodia in a memorandum titled “Actions to Protect U.S. Forces in South Vietnam” (NSDM 57, 1970). Notably, it designated WSAG as the “implementing authority” of measures for Cambodia, suggesting a much reduced distinction between policy-formation and operational implementation in the Nixon White House. Having considered the NSC meeting of April 22, arguably the significant disagreement over a major foreign policy issue suggests that even under Kissinger’s reformed NSC system “insecurity and vulnerability pervaded the government” (Suri, 2007, p.205).

The formation and implementation of Nixon’s Cambodia policy was an intricate process, far removed from traditional foreign policy organs of state. Alterations made by Kissinger to the policy-making process centralised power and led to what was has been described as “a Mini-State Department in the White House under the direction of his Assistant for National Security Affairs” (Schlesinger, 1974, p.190). As suggested by the quote, the changes made set Nixon and Kissinger’s national security apparatus against the Department of State. As a result, the Diplomatic Service and its chief policy experts were kept in the dark over many key decisions. Likewise, only Kissinger accompanied the President in important meetings with foreign heads of state. As a result, the Presidency of Nixon is used by Schlesinger (1974) in his book, The Imperial Presidency, as the central example to exhibit the decline of the traditional separation of powers in foreign affairs.

Right from the first stage of the U.S. involvement, Vietnam and Indochina specialist NSC staff “were not aware of operation Menu” (Siniver, 2008, p.80). Even further detached during the whole process was the Department of State. On March 15, 1969 the secret bombing of Cambodia commenced: the “President ordered immediate implementation of Breakfast plan” (Memorandum of Telephone Conversation, 1969). In contrast, the Department of State released a strategy paper on Cambodia stating that “our general objective would be to restore…the 1954 accords for Cambodia” (Bundy, 1969). For contextual purposes, the 1954 Geneva Accords was an agreement which settled the military situation within Cambodia including the withdrawal of the French Army. The Department of State’s strategy paper was released on the exact same day that that Nixon gave the order to implement Operation Breakfast. This demonstrates how out of the loop the State Department were. Nearer to the end of the Nixon Administration when the U.S. were maintaining the regime of Lon Nol; this set-up had changed little. Siniver (2008) reveals that while WSAG were establishing an aid fund to Lon Nol channelled through Australia, the Department of State were pondering whether to even deliver medical supplies to the Khmer Republic. The diminished role of the State Department during the Nixon years is highly relevant to the central emphasis of this chapter, as it reduced the extent to which the administration could be held to account.

Dallek reveals that during the first 100 days of the Nixon Presidency, “Kissinger had 198 individual or group meetings with the President”; in contrast, during the same period, Secretary of State William Rogers and Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird “attended only thirty meetings” (2007, p.100). Simultaneous to the decline in the influence of the State Department and Department of Defense, Schlesinger notes that “…White House aides were no longer channels of communication” (1974, p.222). These aides instead became more powerful, superseding figures such as the Secretary of State. Notably, while these figures appeared to be as powerful as cabinet members; “they were not, like members of the cabinet, subject to confirmation by the senate or…interrogation by committees of the Congress” (Schlesinger, 1974, p.222). Hence, by relegating key office holders such as the Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense, key actors in the Nixon-Kissinger administration were able to conduct operations in Cambodia free of any congressional oversight. As a result of these major changes in the policy-making process, Shawcross’ assertion that the main features of Nixon’s foreign policy “were subjected to no formal debate at all” (1979, p.84) is therefore credible.

Aside from the lack of accountability; another area worthy of scrutiny is Nixon’s handling of the U.S. military, in particular the U.S. Air Force (USAF) for operations in Cambodia. Despite being able to “call upon sixty planes a day. Each plane could carry a load of approximately thirty tons of bombs” (Shawcross, 1979, p.23); Nixon was far from satisfied with the U.S. military’s implementation of his strategy. On December 9, 1970 during a telephone conversation with Kissinger, Nixon stated “The whole goddamn Air Force over there farting around doing nothing…it’s awful” (Nixon, 1970). Nixon stressed that the “dammed Air Force can do more” (1970); he even markedly proposed that propeller aircraft, used by the National Guard, were made air worthy for use in Cambodia. It wasn’t just political institutions that Nixon antagonised, his approach to Cambodia made nemeses in all areas of the U.S. government.

Due to the uncompromising secrecy of the policy, very few military commanders were told about Operation Menu – even “The Secretary of the Air Force, Dr. Robert Seamans, was kept in ignorance” (Shawcross, 1979, p.29). This meant pilots were forced to lie to superiors about sorties – which at times – were directed by a “back channel to the military” from Washington (Siniver, 2008, p.92). This situation was undesirable for practical and moral reasons; it in effect it bypassed the military code of conduct and chain of command. This ultimately helped to bring down the policy itself. By 1973, Shawcross (1979) reveals that Major Hal Knight had written to Congress to complain about the secret bombing, this was for two reasons. First, that they been bombing a country which was not at war with the United States. Secondly, about the final reporting process of the bombing targets, which “flew in the face of basic military principle” (Hersh, 1983, p.61). These revelations about Operation Menu also hindered Nixon’s subsequent policy, Operation Freedom Deal; “by late 1972 Congressional criticism of the bombing was coming to a head, fuelled by revelations to Congress by former servicemen of the earlier secret Menu operations” (Morocco, 1988, p.148). This points out that Nixon’s obstinate and uncompromising approach would come to undermine his policy.

It is generally agreed that Nixon ran a highly centralised political operation (Suri, 2007; Siniver, 2008; Schlesinger, 1979; Dallek, 2007). This meant distant government departments and agencies had significantly less influence on policy-making in the Nixon White House. Tensions with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in particular affected the U.S. approach to Cambodia. Nixon saw the CIA as “liberals who…might consider themselves socially superior to him” (Siniver, 2008, p.107). Siniver claims that his “had a detrimental impact on the president’s ability to manage the crisis without bias” (2008, p.107). On reflection, the general argument put forward by aforementioned scholars, that Nixon had bias against the CIA, has potency. The example of the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) – the North Vietnamese Military Headquarters for operations in South Vietnam can be examined. The destruction of COSVN was heralded by Nixon as one of the primary motives for the 1970 invasion of Cambodia. Yet, Powers reveals that the “CIA conceded that they did not have triangulation” (1981, p.279) of the suspected facility. As a result, the U.S. had invaded a country to destroy a target which nobody was sure actually existed (Powers, 1981). This demonstrates that Nixon’s prejudice of the ‘socially superior’ intelligence agencies carried bearing on the decision-making process towards a major pillar of Nixon’s approach to Cambodia: the decision to invade.

In summary, Nixon’s lack of faith in surrounding institutions combined with his obsession with secrecy meant that policy-making during this period produced “a charade of secrecy, back-channelling, exclusion, and evasion, orchestrated from the first by Nixon and Kissinger” (Siniver, 2008, p.109). The counter view can be recognised that Nixon is not unique but part of a wider tradition of Cold War U.S. leaders who would act alone in foreign policy decisions such as Presidents: Harry S. Truman, Lyndon B. Johnson, John F. Kennedy. Despite this, it is clear that the Nixon Presidency took centralised decision-making to a new level. The political culture associated with the downfall of the Nixon presidency, known as Watergate, accompanied an ‘imperial’ approach to foreign policy-making (Schlesinger, 1974). After the decision was taken to invade Cambodia, 250 State Department officers signed a letter to the Secretary of State William Rogers, criticising U.S. involvement. Indeed, the backlash within the executive branch – including from within the military namely personnel involved with Operation Menu and even members of Kissinger’s NSC staff – would soon spread to the legislature. From 1969 to 1973, further opposition to Nixon’s Cambodia campaign only increased his resolve and determination. Even to the extent that “the secret became more important to the White House than the bombing” (Hersh, 1983, p.54).

Congressional offensive against U.S. involvement in Cambodia

Schlesinger (1974) concedes that the Cold War and age of global intervention, reduced the role of Congress in U.S. foreign policy. While this is generally agreed amongst scholars- (Dumbrell, 1997; Gaddis, 2007; Walton, 2012), it is equally convincing that the most successful pillars of U.S. foreign policy such as the Marshall plan and the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) were products of Executive-Legislature cooperation. This consideration was not reflected in any way by Nixon’s approach to policy-making – as set out in the last section– he operated within a custom-built and centralised process, far removed from the traditional foreign policy bureaucracy. As a result, the Presidency of Nixon could be described as a paradox as it led to a “transition towards greater Congressional impact on foreign policy” (Astor, 2006, p.124). This section will make the case that Nixon’s policy on Cambodia contributed to the commotion within U.S. domestic politics at the time. Likewise, it could be viewed as the chief cause for dire relations between Capitol Hill and the White House – this snapping point would lead to permanent changes within U.S. policy making.

Despite the significant opposition to the Vietnam War by members of Congress and the public, Congress did not start to exercise its constitutional authority until covert bombing operations in Cambodia were revealed. Despite the side-issue status awarded to Cambodia by some scholars, the country still warranted its own autonomous and top-secret policy approach from the White House. The secret B-52 bombing raids were first revealed by William Beecher of the New York Times in 1969 (Clymer, 2004b, pp.6-7), generating large condemnation and galvanizing the anti-war movement. In response, the administration asked J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to find suspected leaks within the government. An NSC aide to Kissinger, Morton Halperin, was among several staff members to be wiretapped; with the FBI ordering “not to keep any records of the wiretaps” (Reeves, 2001, pp. 75-76). Later on, Nixon’s infamous ‘plumbers’ unit was – which used for spying on political opponents – could be viewed as an offshoot of the practise used following the bombing was made public. Jentleson states that “Watergate wasn’t a foreign policy scandal” (2014, p.176). Despite this, on reflection, parallels can be drawn between the unlawful political activities of the Nixon Administration and its secretive, ‘imperial’ approach to foreign policy. This indicates that Nixon sought to centralise power in domestic policy, in the domains of U.S. external relations and national security.

On top of the Operation Menu bombing which began in 1969, Nixon’s decision to publically announce the 1970 Invasion of Cambodia furthered public apprehension. The reaction to the invasion was astonishing: one week later, four students had been killed by the National Guard and 100,000 protesters had gathered outside the White House. Due to the unprecedented scale of protest; the “anti-war movement was an important influence on U.S. policy” (Jentleson, 2014, p.176). On reflection, it is doubtful that the protesters – of whom Nixon referred to as “bums” (Nixon cited by Bundy, 1998, p.156) – provoked any change of Nixon’s stance. Yet, arguably the main outcome was its effect on Congress. Congress, in particular the Senate, was irritated after Nixon failed to consult them about U.S. action in Cambodia. Thus, Congress reflected the public mood by passing the 1971 Cooper-Church Amendment, which prohibited American military involvement in Cambodia. In the White House, the situation was so tense that Nixon’s Chief of Staff, Harry R. Haldeman, on May, 9 1970 recorded in his diary: “I am concerned by his condition [Nixon]. The decision, the speech, the aftermath killings, riots, press, etc.; the press conference” (1994, p.196). Haldeman’s account implies that the domestic uproar, which came in response to Nixon’s unilateral approach to policy-making, impacted the President’s mentality in relation to decision making of policy towards Cambodia.

The U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia, particularly Cambodia, provoked Congress to challenge “the scope of the respective congressional powers and the President’s powers in war-making” (Cooper, 1971, p.60). On January, 5, 1971, the Cooper-Church amendment to the Foreign Military Sales Act legislated that U.S. forces would withdraw from Cambodia by June, 30 1970, including the termination of support for the Khmer National Armed Forces (FANK). The amendment forms a significant chapter in U.S. foreign policy, in part due to its status as the “first-ever decision by Congress to restrict presidential war powers” (Siniver, 2008, p.87).

By 1973 Congressional criticism of Operation Menu had amplified. The Senate Armed Services Committee undertook a review into allegations that the U.S. Air Force made thousands of secret B-52 raids into Cambodia. Senator Stuart Symington concluded that the raids had little positive impact, “setting in motion a chain of events which has brought the Cambodian communists to the gates of Phnom Penh” (Symington, cited in Morocco 1988, p.148). Aside from the Senate’s negative perception of U.S. involvement in Cambodia, there were further reasons for concern in regards to the Congressional stance on the matter. The decision to allocate funds for the bombing of a neutral country without any consultation with Congress “raised serious questions as to the constitutionality of the actions” (Morocco, 1988, p.149). In addition, the administration falsified the official records of the raids. Shawcross (1979) reveals that missions over Cambodia were in fact recorded to have taken place over Vietnam. As a result, it was proposed that the charge of falsifying records of U.S. operations in Cambodia should be included in the articles of impeachment against President Nixon. The proposal was defeated in the House of Representatives Judiciary Committee on August 1, 1974 by 26-to-12. Yet just the suggestion itself that the matter of Cambodia could bring down a U.S. president, demonstrates notable significance.

The U.S. Congress overturned Nixon’s veto to pass the War Powers Act of 1973. This requirement meant that the White House would have to consult with Congress within forty-eight hours of the introducing of U.S. forces into conflict. This measure also introduced the sixty-day rule, that the President must achieve permission from both houses if U.S. operations are to continue after the period of initial deployment. It is worth considering that these measures represent permanent changes to U.S. policy-making. Notably, the War Powers Act also repealed the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which underpinned U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution allowed President Johnson to sanction unconstrained presidential authority to escalate the war in Vietnam – described by Siniver as a “carte blanche” or blank cheque (2008, pp.71-72). This is significant, as it demonstrates that the congressional offensive against presidential war powers not only attended to U.S. action in Cambodia, but wider American participation in the region. Aside from addressing direct military involvement, Congress directed efforts at limiting military and economic aid to Cambodia. Aid, like the use of bombing raids, stood as a vital component of Nixon’s Cambodia strategy. It was seen to be critical in order to enhance the capabilities of the Cambodian forces whilst simultaneously targeting Communist forces and adversaries of the pro-U.S. Khmer Republic. After years of President Nixon’s misuse of public funding for support to the Khmer Republic, which placed the desires of Lon Nol as supreme to constitutional procedure, the U.S. Congress attempted to limit the ability of the president.

Largely, Congress had managed to reduce the U.S. role in Cambodia. Yet Nixon continued the air war over Cambodia and military aid via the Military Equipment Delivery Team, Cambodia (MEDTC): which was active up until 1975. Overall, the Khmer Republic was reliant on U.S. support. Accordingly, Kissinger (1979) places the blame for the loss of Cambodia on Congress for interdicting further bombing in 1973. Yet this assessment can be challenged. In October 1973, in a message to Admiral Noel Gayler, Commander in Chief, Pacific Command of the U.S. Navy, the head of MEDTC, Brigadier General Cleland, admits that: “in strategic terms, the government at Phnom Penh had been on the defensive since 1971 and could not regain the initiative” (Cleland cited by Nalty 2000, p.412). This suggests – regardless of the actions of Congress taken in 1973 – Lon Nol faced evitable defeat, thus Nixon’s strategy of supporting Lon Nol was unsustainable. Unsustainable in the external setting, as even with U.S. support, under Lon Nol’s incompetent leadership, FANK were unable to convert the high levels of American assistance into military gains. Also, unsustainable in the domestic setting, as the secretive and belligerent nature of Nixon’s strategy alienated Congress, within an existing environment of estranged relations in Washington. Even a sympathetic biographer of Kissinger admitted that “the domestic divisions…destroyed the remaining prospects for a sustained policy in Southeast Asia” (Isaacson, 1992, p.270).

After the Watergate scandal was exposed, Nixon’s popularity fell, on top of the already high levels of resentment towards the U.S. Government from the growing anti-war movement. Nixon’s domestic downfall would weaken his control of foreign policy agendas. While it is largely agreed, that the Vietnam War aided the downfall of the Nixon Administration, it has been argued that Cambodia in particular took public discontent to to new height. This view in endorsed by political historian Robert D. Johnson: “The Cambodian invasion…served only to incite the public further…more so than any other single event during this tragic era” (1995, p.98).

Opposition to U.S. involvement in Cambodia was so great that leaders of the U.S. Senate would openly disagree with their President. Prior to this, such dissent on a matter of war and peace was unprecedented. After years of secret bombings and military incursions. Opposition to U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia, particularly Cambodia, was widespread within Congress and the public. Nixon’s approach to Cambodia specifically stands as a central example of the excesses of Presidential power. After the secret bombing was exposed, and the announcement of the 1970 invasion, anti-war sentiment went through the roof. In qualification, Bundy discloses that “In March [1970], 46 percent favoured withdrawal…by January 1971 [it had risen] to 73 percent” (1998, p.160). This, amongst other causes, drove a president – with one of the strongest electoral mandates in U.S. political history – into resigning. It could be argued that one legacy created from this period is scepticism, even fear, within Congress of presidential power. Even so that today, this remains an unsolved issue. In short, the evidence suggests that efforts by Congress to limit war powers of the executive branch came as a reaction to the centralised and unilateral nature of policy-making during the Nixon Administration.

Conclusion

On January 27, 1973, President Nixon claimed he had achieved the ambiguous objective of “peace with honor in Vietnam and in Southeast Asia” (Nixon, 1973). In reality Nixon’s policies, if anything, led to increased conflict and national humiliation. Moreover, the U.S. had no “alternative for ending the war except the application of more force”; under Nixon the U.S. escalated its role in Cambodia, which has been described as an “erratic course” (Dallek, 2007, pp.107-188). The escalation, principally the secret bombing and 1970 Invasion of Cambodia, was directly linked to wider U.S. strategic aims in Vietnam. Cambodia has been labelled by Shawcross (1979) as a Sideshow, similarly, as a pawn on a superpower chessboard by Haas (1991). Nevertheless, while there is merit to these points, it can also be argued that to simply view Nixon’s actions in Cambodia as a classic act of Cold War realpolitik is misguided. It has been shown that Cambodia warranted its own autonomous approach from the Nixon White House and underpinned Nixon’s overall strategy for Southeast Asia. This project has made the case that by 1973, Nixon’s policies ignited out-and-out war in Cambodia and political conflict in Washington. To conclude, it can therefore be said that U.S. policy towards Cambodia during this period is worthy of higher scrutiny by scholars of U.S. foreign policy.

It was argued in Chapter One that the Nixon-Lon Nol alliance was inadvisable. Indiscriminate U.S. bombing of Cambodia aided communist forces which proved detrimental to the goal of maintaining of a pro-U.S. regime in Phnom Penh. The increased violence and chaos that developed under the U.S. backed Khmer Republic revived historical racial hatred between the Cambodian and Vietnamese people. The consequent Cambodian Civil War during the Khmer Republic – which lasted from 1970 until 1975 – could be seen as a continuation of the U.S. war with Vietnam: fought in a neighbouring territory and paid for with Cambodian blood. While it is true that “to attribute all Cambodia’s suffering solely to decisions made or ratified by President Nixon represents an oversimplification” (Nalty, 2000, p.196), it remains convincing that Nixon’s approach was reckless: viewing Cambodia as a quick fix in addressing the looming American defeat in neighbouring Vietnam.

As noted in Chapter Two, Nixon’s contentious approach to Cambodia was made possible by a highly centralised policy-making process, directed by Henry Kissinger. The policy-making process under Nixon and Kissinger defied tradition, thus alienating not only the legislature but also major institutions within the executive such as the Department of State. After the revelations of the secret Operation Menu raids in 1969, the importance of Cambodia within the U.S. domestic sphere was astonishing and led to a “contest of wills between the U.S. Congress and the beleaguered executive branch” (Chandler, 1991, p.225). Consequently, this would lead to permanent changes to presidential war powers and the resurgence of Congress in the field of foreign policy, culminating with the War Powers Act of 1973. Despite the blatant public criticism and Congressional resistance of the Nixon Administration’s policies towards Cambodia, the President was persistent to endure – viewing the capacity to bomb Cambodia almost as a symbol of his presidency. This stubborn approach antagonised Executive-Congressional relations to such an extent that it contributed – beside the illegal political activities known as Watergate – to the downfall of a U.S president.

President Nixon remained in office until August 9, 1974. Equally, the U.S. did not fully relinquish its involvement in Cambodia until just before the fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge in 1975. Yet it is conceivable that the unsustainable nature of the policies implemented between 1969 and 1973 predestined the parallel fate of both Nixon’s presidency and Cambodia. In his memoir, In retrospect, former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara concedes that the U.S. perused the wrong approach towards Vietnam (1995). No such concession has been made on Cambodia by Richard Nixon or Henry Kissinger.

In closing, U.S. policy towards Cambodia between 1969 and 1973 was treacherous because of the political implications in Washington and tragic consequences in Cambodia. Cambodia itself was an independent and somewhat neutral nation in 1969. By 1973, after years of secret bombing and U.S. invasion, Cambodia had been entangled within the neighbouring geo-political conflict in Vietnam. Between 1970 and 1975, “an estimated half-million Cambodians, most of them non-combatants, lost their lives” (Chandler, 1991, p.215). After the victory of Pol Pot, the worst was still to come for the people of Cambodia.

Bibliography

Books

Astor, G. (2006) Presidents at War: From Truman to Bush, The Gathering of Military Power to Our Commanders in Chief, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Bundy, W. (1998) A Tangled Web: The Making of Foreign Policy in the Nixon Presidency, London: I.B. Tauris Ltd.

Chandler, D. (1991) The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution since 1945, United States of America: Yale University Press.

Clymer, K. (2004a) The United States and Cambodia, 1870-1969: From Curiosity to Confrontation, London: Routledge.

Clymer, K. (2004b) The United States and Cambodia, 1969-2000: A Troubled Relationship, London: Routledge.

Dallex, R. (2008) Nixon and Kissinger: Partners in Power, Great Britain: Penguin Books.

Dumbrell, J. (1997) The Making of US Foreign Policy, Great Britain: Manchester University Press.

Gaddis, L. (2007) The Cold War, London: Penguin Books.

Haas, M. (1991) Genocide by Proxy: Cambodian Pawn on a Superpower Chessboard, United States of America: Praeger Publishers.

Hersh, S (1983) The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House, United States of America: Simon and Schuster.

Isaacson, W. (1992) Kissinger: A Biography, United States of America: Simon and Schuster.

Jentleson, B. (2014) American Foreign Policy, United States of America: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Johnson, R. (1995) The Peace Progressives and American Foreign Relations, United States of America: Harvard University Press.

Kiernan, B. (2004) How Pol Pot Came to Power: Colonialism, Nationalism, and Communism in Cambodia, 1930-1975, United States of America: Yale University Press.

Kissinger, H. (1979) The White House Years, Great Britain: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

McNamara, R. (1995) In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam, United States of America: Vintage Books.

Morocco, J. (1988) The Vietnam Experience, War in the Shadows, United States of America: Boston Publishing Company.

Nalty, B. (2000) Air War over South Vietnam 1968-1975, United States of America: Air Force History and Museums Program.

Powers (1981) The Man Who Kept the Secrets: Richard Helm and the CIA, New York: Pocket Books.

Reeves, R. (2001) President Nixon: Alone in the White House, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Schlesinger, A. (1974) The Imperial Presidency, Great Britain: Andre Deutsch.

Shawcross, W. (1979) Slideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia, Great Britain: André Deutsch.

Siniver, A. (2008) Nixon, Kissinger, and U.S. Foreign Policy Making: The Machinery of Crisis, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Suri, J. (2007) Henry Kissinger and the American Century, United States of America: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Tucker, S. (2011) The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History, United States of America: ABC-CLO, LLC.

Walton, D. (2012) Grand Strategy and the Presidency: Foreign Policy, War and the American Role in the World, Abingdon Oxon: Routledge.

Online Archival Documents: The Digital National Security Archive (DNSA)

A Report to the President by the National Security Council. ‘United States Objectives and Programs for National Security’ (NSC-68). April 12, 1950. Available at http://search.proquest.com/dnsa/docview/1679067494/A7CB31683591454BPQ/1 [Accessed 11 January 2016].

Memorandum. ‘Proposal for a New National Security Council System’. December 27, 1968.http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/dnsa/docview/1679068868/B74FBBC589D74894PQ/1 [Accessed 09 February 2016].

Memorandum. ‘Report on Cambodia from President-elect Nixon to Henry Kissinger’. January 08, 1969. Available at: http://search.proquest.com/dnsa/docview/1679103795/A4241085C91546BEPQ/1 [Accessed 11 January 2016].

Memorandum, Department of State. ‘General Strategy and Plan of Action for Viet-Nam Negotiations’. March 15, 1969. Available at: http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/dnsa/docview/1679051228/9C99436ECE424F23PQ/2 [Accessed 13 March 2016].

Memorandum of Telephone Conversation. ‘Order to Implement Operation Breakfast’. March 15, 1969. Available at: http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/dnsa/docview/1679095794/6FAE196E75B44182PQ/9 [Accessed 12 March 2016].

National Security Decision Memorandum (NSDM 57). ‘Actions to Protect U.S. Forces in South Vietnam’. April 26, 1969. Available at: http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.uwe.ac.uk/dnsa/docview/1679090472/5B0AF1C775014649PQ/4 [Accessed 16 January 2016].

National Security Decision Memorandum (NSDM 58). ‘Actions to Protect U.S. Forces in South Vietnam’. April 28, 1969. Available at: http://search.proquest.com/dnsa/docview/1679103122/6E27E07C9633467DPQ/1 [Accessed 16 January 2016].

Memorandum of Conversation. ‘Meeting of WSAG Principals on Cambodia’. May 14, 1970. http://search.proquest.com/dnsa/docview/1679125420/6A4325877A4F4C36PQ/2 [Accessed 02 January 2016].

Memorandum of Telephone Conversation. ‘Bombing of Cambodia’. December 9, 1970. Available at: http://search.proquest.com/dnsa/docview/1679137033/9A78F79B19094DCDPQ/4 [Accessed 15 March 2016].

Cable, United States Embassy Cambodia. Top Secret. ‘Letter from Lon Nol to President Nixon on Military Assistance’. November 10, 1972.

http://search.proquest.com/dnsa/docview/1679103771/3C5A6E28BABF448CPQ/1 [Accessed 02 January 2016].

Internet Sources

Richard Nixon: Inaugural Address, January 20, 1969. The American Presidency Project. Available at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=1941 [Accessed 27 November 2015].

Meeting of the National Security Council, April 22, 1970. Document 248. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v06/d248 [Accessed 12 March 2016].

Richard Nixon: Address to the Nation on the Situation in Southeast Asia., April 30, 1970. The American Presidency Project. Available at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=2490 [Accessed 08 December 2015].

Richard Nixon: Address to the Nation on the Cambodian Sanctuary Operation, June 3, 1970. The American Presidency Project. Available at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=2530 [Accessed 14 December 2015].

Richard Nixon: Address to the Nation Announcing Conclusion of an Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam. January 23, 1973. The American Presidency Project. Available at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=38 [Accessed 14 December 2015].

Owen, T. and Kiernan, B. (2006) Bombs Over Cambodia, Available at: http://www.yale.edu/cgp/Walrus_CambodiaBombing_OCT06.pdf [Accessed 12 December 2015].

Written by: Oliver Omar

Written at: University of the West of England, Bristol

Written for: Dr Stephen McGlinchey

Date Written: April 2016

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- ‘Almost Perfect’: The Bureaucratic Politics Model and U.S. Foreign Policy

- Jimmy Carter’s Liberalism: A Failed Revolution of U.S. Foreign Policy?

- The Puzzle of U.S. Foreign Policy Revision Regarding Iran’s Nuclear Program

- An “Invitation to Struggle”: Congress’ Leading Role in US Foreign Policy

- Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge: U.S. Arms Transfer Policy

- Two Nationalists and Their Differences – an Analysis of Trump and Bolsonaro