During the Cold War a narrow ‘traditional’ concept of security, focused on military threats to the nation state, was dominant. After its end however, there was a proliferation of theorising that attempted to explain security in the context of an evolving threat landscape, resulting in the widening and deepening of the field. In the 21st Century the Global War on Terror, the Arab Spring, and continued insecurity in Sub-Saharan Africa have all led to major debates within security theory but none have yet proved transformational. The threat now at the forefront of global consciousness however, could prove to do so, with the recent UN Security Council resolution determining that “ISIL constitutes a global and unprecedented threat to international peace and security” (UN Security Council, 2015). In this essay I’m going to examine the analytical challenges that Islamic State (IS) presents to security theory and whether there needs to be a fundamental shift to explain and support appropriate action to the threat landscape produced by IS.

I will begin with a brief overview of current security theory, focusing on the difference between ‘traditional’ (Traditional Security) and ‘widener-deepeners’ (Critical Security) approaches before setting out the functions of IS and how they can be reflected in a threat environment. Using this threat environment I will then examine the challenges IS presents to Traditional Security (TS) theory and conclude that the narrow boundaries of this approach limit its usefulness as a concept to explain and respond to IS. I will then reflect on IS within Critical Security (CS), based heavily on Fierke’s (2007) interpretation, to identify whether a constructivist approach enables CS to overcome the challenges faced in TS. I determine here that although CS provides a better fit for the dynamics of IS, there are still some fundamental questions that remain unanswered. I conclude on whether the rise of IS requires a fundamental shift in security thinking or whether it will be through a further evolution of CS, and making full use of the freedom afforded by a constructivist approach.

Security Theory

In this section I will outline the dimensions along which competing theories are organised, give a brief overview of the key debates in Security Studies and outline the two overarching approaches that I will use to analysis the challenges IS poses to security theory.

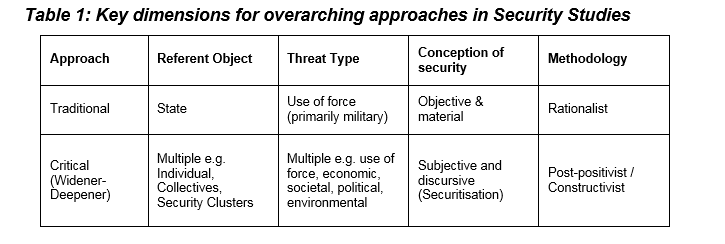

Analytical approaches in Security Studies have evolved over time, driven by a combination of great power politics, technology (primarily arms and communications), world events, academic debate and institutionalisation (Buzan and Hansen, 2009). There is a lack of consensus on the meaning of security with some suggesting this is due to security being insufficiently explicated (Baldwin, 1997:10), whilst others have labelled it an ‘essentially contest concept’ (Buzan, 1991), meaning that the term is value laden to the extent that there cannot be a “single definition which corresponds to reality ‘out there’ across time” (Fierke, 2007:32). So that I can appropriately examine the challenges IS poses to security theory I will briefly outline how the key debates have shaped the field with reference to the two overarching approaches, set out in Table 1.

The first debate is what the referent object is and what threat types we are securing against. This sets the boundaries of what can be secured. During the Cold War the field was dominated by a ‘traditionalist’ approach, where the focus of Security Studies was war and it could be defined as “the study of threat, use and control of military force” (Walt, 1991:212). The emphasis was on the nation state and the threat of interstate war, with the state the referent object within security. The end of the Cold War, and the realisation that there were other objects to secure from multiple types of threat, resulted in the branching out from the state-centric, military-political conception of security. The ‘wideners’, added economic, societal, political and environmental to military threats and the ‘deepeners’ added additional units of analysis that could be the referent object in addition to the state (Cavelty and Mauer, 2010). Comparing Walt’s definition to that of Buzan, who stated that security is “the pursuit of freedom from threat and the ability of states and societies to maintain their independent identity and their functional integrity against forces of change” (Buzan, 1991:432), demonstrates the shift in thinking and the expansion of the scope of security.

The second debate relates to the approach to epistemology, which concerns how security is defined and the principles and guidelines for how knowledge is acquired. ‘Traditionalists’ have focused on the objective material security threats studied from a positivist/rationalist viewpoint. ‘Wideners-deepeners’ have focused on security being a political process that can transform in meaning over time, making it a contested term. They have focused on subjective and discursive conceptions from a post-positivist/constructivist perspective (Buzan and Hansen, 2009; Cavelty and Mauer, 2010).

Finally, I will also introduce the concept of securitisation, which emerged from the Copenhagen School and fits into CS. Only by presenting an issue in security terms can it become a security issue. For this to happen you require an actor who can declare a threat to a referent object and an audience that accepts it as an existential threat to that object (Waever, 2005:153). This will be pertinent when I analyse the security of the population living within IS, and the question of who they have to securitise their threats.

Defining IS and Its Threat Environment

Understanding the threat environment is a pre-requisite for analysing the challenges IS poses to TS and CS theories. I will therefore start by defining the functions of IS before placing them into the threat environment.

Over the last 10 years IS has demonstrated the characteristics of: a non-state actor, through its insurgency against the US in Iraq and participation in the Sunni-Shia civil war; a transnational terrorist organisation, by planning and carrying out major global attacks; a transnational religious body, by using modern communications to proliferate its ideology and recruit new joiners through hijrah (emigration) to the Caliphate; a state, by capturing territory and declaring a Caliphate; and a regional criminal organisation, by perpetrating human rights abuses and by securing illicit revenue streams.

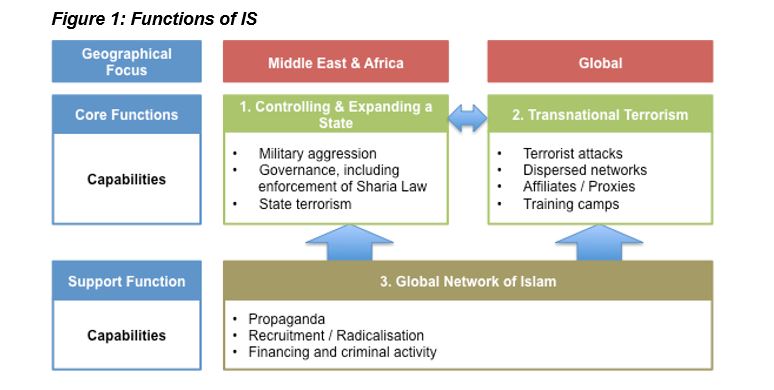

This makes describing IS as a single homogeneous entity a challenge and I therefore believe, as I examine below, the best way to consider IS within security theory is to break it out into three distinct functions. These can each be considered as referent objects and placed into the threat environment. They are two core functions of (1) Controlling & Expanding a State and (2) Transnational Terrorism, supported by (3) a Global Network of Islam.

1. Controlling and Expanding a State (Core Function)

The 1933 Montevideo Convention sets out the qualifications a state must have under international law as: (1) a permanent population; (2) a defined territory; (3) government; and (4) capacity to enter into relations with other states (Montevideo Convention, 1933:Article 1). Whilst IS controls population and territory, it is the population and territory of invaded states, and its governance is only in embryonic form. In addition, it is important to consider how IS has established its authority and control, through the extreme violence and cruelty against minorities, civilians and enemy combatants (Yihdego, 2015). As well as further damaging its legitimacy as a state, this behaviour can be usefully considered in the context of state terrorism, defined as:

“The intentional use or threat of violence by state agents or their proxies against individuals or groups who are victimized for the purpose of intimidating or frightening a broader audience” (Jackson et al., 2009)

It also completely rejects the sovereignty of other states (Bileat, 2015), which directly conflicts “The territory of a state is inviolable” (Montevideo Convention, 1933:Article 11). Finally, the response of the international community outlines that it is unlikely to be able to enter into relations with other states, as a state.

“ISIL is certainly not a state…It is recognised by no government nor by the people it subjugates. ISIL is a terrorist organization, pure and simple.” (Obama, 2014)

However, it isn’t disputed that IS holds certain state-like properties. It controls a conventional military force, holds territory and provides limited services to the population it controls. Therefore, even though it is not legitimate, it is useful in the context of security theorising to define IS ‘the State’ as a core function, characterised by military expansionism, state terrorism, limited governance and strict enforcement of Sharia law.

2. Transnational Terrorism (Core Function)

IS’s credentials as a global terrorist threat are not in dispute after recent attacks in Europe, Africa and the Middle East, demonstrating its range of capabilities and a breadth of targets. Various scholars (Wood, 2015; Williams, 2015; Yihdego, 2015) suggest IS is a new type of terrorist organisation due to its hold of territory and conventional military capability. However, the terrorist acts (threat) experienced by threatened populations remains the same, irrespective of whether IS holds territory. Therefore, I will proceed by maintaining transnational terrorism as a core function; separate from IS ‘the State’.

3. Global Network of Islam (Support Function)

The final function of IS is the global network it has leveraged to support the advancement of its two core functions. Its adaptability to modern technology, use of the Internet as a propaganda tool (Yihdego, 2015) and its extreme variety of Islam have all contributed to it becoming successful at recruiting foreign fighters and strengthening its state and terrorism functions.

In addition to linkages to the core functions of IS, I believe that its global network is an issue for security. A challenge currently facing the international community is the battle against radicalisation, which is not occurring at the state or terrorism level, but through this expanded network. It is therefore important that it is considered as a separate support function sitting within IS.

Identifying the Threat Environment

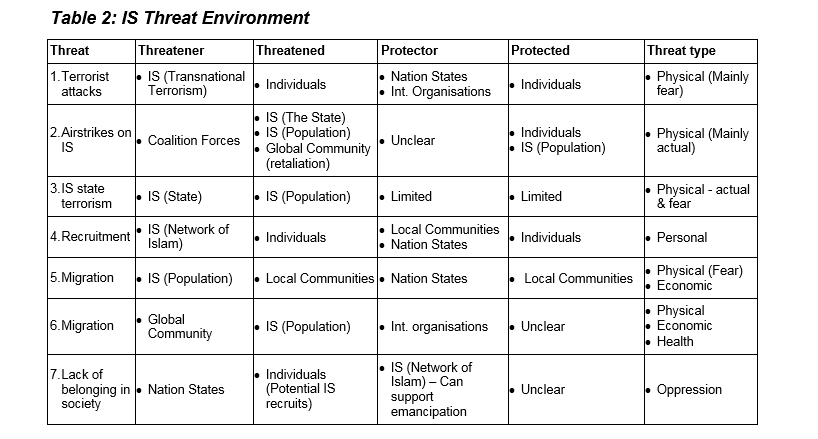

Having defined the functions of IS I can now place them in the threat environment. I will use Fierke’s construction of security as a set of relationships, which includes a threatener, the threatened, the protector and the protected (Fierke, 2007:46). An initial review of the threat landscape demonstrates the complexity and the challenges faced with providing an approach that can consider the diversity of threats experienced.

Using this threat environment as a guide for what the theory needs to encompass, I will now consider the challenges IS poses to TS and CS.

Challenges to Traditional Security Theory

There are three major challenges posed by IS to TS. Firstly, the use of the state as the referent object when considering threats to the Global North. Secondly, realism assumptions which presume IS behaves as a rational actor. Thirdly, the ‘narrowness’ of TS leaves a major gap in the provision of security for the population living under IS.

Are States a Suitable Referent Object for Threats to the Global North?

‘Traditionalists’ privilege the state as the referent object and focus on external threats. The threats IS project externally experienced in the Global North are associated with terrorist acts, migration and the radicalisation of individuals for recruitment. These threats transcend borders and IS ‘the State’ is not the threatener in any of these instances. The threateners are the other core functions that TS doesn’t recognise (Terrorism & Global Network). There is the challenge that you can address the terrorist attacks through addressing IS ‘the State’ but I do not believe this is the case. IS’s lack of willingness to compromise (Hamid, 2015), its rallying call for Global Jihad, and the fact that a high proportion of its terrorist attacks are carried out by ‘sympathisers’ rather than directed by its leadership (Hegghammer and Nesser, 2015), limit the usefulness of these threats being considered with the state as the referent object.

In support of TS, the state does play a role as protector against terrorist attacks, primarily through the intelligence services and border controls. However the state as the referent object is still limited as it is not able to recognise the role that a range of actors play to protect migrants (NGOs) and challenge radicalisation (Community groups, friends, family). Finally, the fact a Coalition is now bombing IS ‘the state’, within another state, challenges TS theory, which only considers external state on state threats. Intervention in internal affairs amounts to a challenge to sovereignty that is prohibited within the approach.

In summary, the complexity of the relationships and actors means that addressing IS using only states as referent objects limits the ability to provide a complete view of the threat landscape.

Do Realism Assumptions Hold?

The second challenge is whether IS resembles a traditional state actor for realist theories to be applicable (Buzan and Hansen, 2009). In particular, can IS be considered rational i.e. selfish, self-maximising and preoccupied by its own survival. IS’s objectives are to expand the Caliphate whilst eliminating neutral parties through either absorption or elimination, in preparation of an apocalyptic battle with the West (Cockburn, 2015; Weiss, 2015). Although IS has demonstrated that it is a strategic actor (Williams, 2015), a combination of its beliefs and contradictory objectives mean that it is difficult to consider it rational, within the frame of realism and what is expected from a rational state. Two brief examples demonstrate this.

Within TS, a rational actor is preoccupied with its own survival. The intensification of its foreign terror attacks in 2015 has provoked a predictable international response that threatens its survival (Hamid, 2015). In addition, if considering IS only as a state, carrying out terrorist attacks do not appear self-maximising, unless it is considering it a key driver of recruitment.

Secondly, the violence that it has distributed in Syria and Iraq, whilst supporting its objective of ‘absorption or elimination’, is also likely to alienate IS from the population and have a negative impact on its ability to govern and expand the Caliphate in the long-term. This also challenges IS’s rationality within the boundaries of TS.

What about Threats Projected Internally?

The final challenge, in part due to the narrowness of the conditions set in TS, but also due to the Global North’s dominance of security discourse, is the inability of TS to recognise the security of the population living within IS held territory. It considers threats between states but not the threats posed by a state on its population, leaving no actor to play the role of protector. In IS territory, these threats have been so extreme that you could argue they amount to state terrorism. In addition to being threatened by IS, the population has to contend with threats from Coalition airstrikes. Once more, state led attacks on IS ‘the state’ do not privilege the population with security status and therefore it remains unprotected.

From the examination set out above, I believe it is clear that although TS does allow us to understand some of the dynamics relating to the threat environment, the complexity of the relationships, the argument that IS breaks realism assumptions and the inability of TS to address the security of the population mean TS is limited in its use.

Challenges to Critical Security Studies

Before addressing challenges to CS, I will first set out how CS is able to overcome some of the issues faced in TS. Firstly, it allows us consider alternative referent objects and include internal as well as external threats. By defining relationships in ‘security clusters’, different participants can be mapped out and understood. The actors and objects in Table 2 are examples of security clusters. Secondly, it allows a different construction of the concepts and epistemology of security, allowing a more flexible approach to understanding and responding to threats. For example, the ability to be able to frame IS in its own historical context is hugely valuable to help understand its behaviour, rather than having to attribute specific values based on realist assumptions. There are however two challenges I will consider with CS. Securitisation and the managing the challenge of complexity.

Does Securitisation Prioritise The Right Threats?

The ‘Securitisation’ of IS threats outlines a major challenge posed to CS. By making threats a discovered process rather than a static environment (Fierke, 2007:99), the actors who ‘securitise’ the threats, and the willingness of an audience to accept them plays a major role in how threats are constructed and addressed. Significantly, the constructed ‘perceived’ threat often varies from the actual observed threat. Both IS, through its propaganda, and the global community, primarily through the media and politicians, have played a role in ‘securitising’ threats. This has led to threat prioritisation, which when looked at objectively might not appear logical and has significant bias towards security interests of the Global North.

For example, it was only after terrorist attacks in Paris that the UNSC declared IS “an unprecedented threat to international peace and security” (UN Security Council, 2015), despite the fact that IS had carried out similar acts in the Middle East for 10 years. This also highlights the challenge of the security of silence, whereby the “subject of security has no, or limited, possibility of speaking its security problem” (Hanzen, 2000:295). In the case of the population under IS control, there is limited opportunity to voice security concerns and to do so presents a real risk to their physical security. What’s more, even if they could articulate their plight, as actors they have limited influence in being able to convince the audience that might offer protection to act. In the case of IS, Coalition forces have securitised the threat of terrorism on the Global North and reacted with airstrikes which could be construed as terrorist acts on the population under IS control.

Therefore, despite CS potentially giving the population referent object status, the inability for them to ‘securitise’ the threats they face means they still remain vulnerable and deprioritised.

Does The Expansion Create Unmanageable Complexity?

The other challenge that IS poses to CS is its complexity as an actor, and the fact that so different security relationships are created between different referent objects and threat types. It could be contended that the expansion this requires results in some loss in conceptual rigour that can be maintained in the ‘narrow’ definition (Walt 1991:213). In essence, the flexibility of CS is a strength and a weakness. It can provide a frame to analyse the threat landscape of IS however it creates complexity by opening up the number of interested parties and the subjective nature of the security, make finding agreement on policy decisions to address threats challenging.

Relating it to an example for IS, you could consider security as emancipation: “the freeing of people, as individuals and collectives, from contingent and structural oppressions” (Booth, 2005:181). Within this definition you explain a security relationship whereby nation states are subjecting individuals to the threat of structural oppression through lack of opportunities or exclusion from society (Table 2: Threat 7). This in turn leads them to seek security and belonging by joining IS. This is a very different conceptualisation of security to the threat from a terrorist attack but can fit within the same framework. Although from an academic perspective this does not create a major issue, when it comes to transferring the theory into policy the breadth of what needs to be considered and underlying political power relations mean implementation may be challenging. The multiplication of actors, allowance for subjectivity in CS, different types of security and the power relations of interested parties are all likely to challenge the ability to create a coherent and consistent strategy that is able to address the security concerns of all those threatened.

Having set out the challenges posed by IS to CS, I will now conclude by setting out how IS can be constructed within existing security theory, considering the challenges it presents.

Conclusion

To examine the challenges IS poses to security theory it was first necessary to define the functions of IS and lay out how these functions related to the threat environment. Within this threat environment, I set out the key that TS is of limited used due to the state being privileged as the referent object, IS breaking realism assumptions and limited consideration for security of the population under IS control. CS addresses some of these challenges but also faces its own limitations, including securitisation of threats and the complexity created when making security broader and more discursive. I will now bring together my thinking to outline how IS might be considered within security theory, and whether this constitutes a fundamental shift in thinking.

The component parts of IS have all been seen before and theorised in other actors, but not together as a single entity. I believe there is real value in acknowledging the identity of the functions of IS separately, whilst also recognising the linkages between them. Whilst the international community continues to reject IS ‘the state’ and treats it as an un-Islamic terrorist organisation, it will be unable to fully frame IS within security theory. I also believe that by recognising the different functions you can also remove some of the complexity related to framing IS within security. For the example of emancipation I used earlier, you could consider a response to the function of IS focused on the Global network of Islam, whereas any military response could be considered against IS ‘the state’.

I also think it is important to follow a constructivist approach, rather than rationalist, allowing for a continuous process of change to the identities of actors. By considering the formation of IS and the gradual polarisation between Western and Islamic identity (Fierke, 2007:89), a better understanding of the threat environment can be gleaned. This does allow for potential exponential growth of what is termed security and therefore I propose the following limitations in terms of the type of threat addressed. For addressing the threats from IS ‘the state’ and IS ‘the terrorist’ I would limit this to physical security (use of force). The current threat landscape is dominated by the threat of physical security even though it also creates multiple insecurities such as economic, political and food. For the threats that are not from IS but relate to it, a wider definition of security could be used to better understand and respond to them.

Finally, there is a need to ‘securitise the silence’ of the IS population and it is here that major international organisations have a responsibility to ensure that the vulnerable are given a voice, potentially leveraging the weight that human security has managed to gain with policy makers. The discourse is still dominated by the Global North and the interests of nation states but that does not mean that the vulnerable should be ignored.

In conclusion, IS is a complicated actor that causes challenges to security theory. However, as set out above, I do not believe that it requires a fundamental re-think as the constituent parts of a theory that can address IS are already in place and need to be brought together in a further iteration of CS.B

Bibliography

The Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States art. 1, Dec. 26, 1933, 165 L.N.T.S. 19 (1933).

Baldwin, D. (1997) ‘The concept of security’, Review of International Studies, 23(1), pp. 5–26. doi: 10.1017/s0260210597000053.

Bielat, H. L. (2015) Islamic state and the hypocrisy of sovereignty. Available at: http://www.e-ir.info/2015/03/20/islamic-state-and-the-hypocrisy-of-sovereignty/ (Accessed: 6 December 2015).

Booth, K. (2005) Critical Security Studies and World Politics. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Buzan, B. (1991) People, states and fear: National security problem in international relations. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Buzan, B. and Hansen, L. (2009) The Evolution of International Security Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cavelty, M. D. and Mauer, V. (2010) The Routledge Handbook of Security Studies. 1st edn. New York: Routledge.

Cockburn, P. (2015) The rise of Islamic state: Isis and the new Sunni Revolution. United Kingdom: Verso Books.

Fierke, K. M. (2007) Critical Approaches to International Security. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishing.

Hamid, S. (2015) Is There a Method to ISIS’s Madness?. Available at: http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/11/isis-rational-actor-paris-attacks/417312/ (Accessed: 29 November 2015).

Hansen, L. (2000) ‘The little mermaid’s silent security dilemma and the absence of gender in the Copenhagen school’, Millennium – Journal of International Studies, 29(2), pp. 285–306. doi: 10.1177/03058298000290020501.

Hegghammer, T. and Nesser, P. (2015) ‘Assessing the Islamic State’s commitment to attacking the west’, Perspectives on Terrorism, 9(4).

Jackson, R., Murphy, E. and Poynting, S. (2009) Contemporary state terrorism: Theory and practice. 1st edn. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Obama, B. (2014) Statement by the president on ISIL The White House. 10 September.

UN Security Council Resolution 2249, Threats to international peace and security caused by terrorist acts S/RES/2249 (20 November 2015)

Waever, O. (2005) ‘The Constellation of Securities in Europe’, in Globalization, security, and the nation-state: Paradigms in transition. United States: State University of New York Press.

Walt, S. M. (1991) ‘The renaissance of security studies’, International Studies Quarterly, 35(2), pp. 211–239. doi: 10.2307/2600471.

Williams, M. (2015) ‘ISIS as a strategic actor: Strategy and counter-strategy’, The Mackenzie Institute – Security Matters, 15 April. Available at: http://www.mackenzieinstitute.com/isis-strategic-actor-strategy-counter-strategy/ (Accessed: 29 November 2015).

Wood, G. (2015) ‘What ISIS Really Wants’, The Atlantic (March).

Yihdego, Z. (2015) The Islamic ‘State’ challenge: Defining the actor. Available at: http://www.e-ir.info/2015/06/24/the-islamic-state-challenge-defining-the-actor/ (Accessed: 4 December 2015).

Written by: Robert Unwin

Written at: SOAS, University of London

Written for: Zoe Marriage

Date written: December 2015

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Anomaly of Democracy: Why Securitization Theory Fails to Explain January 6th

- Is Security Possible? The Use of Face Coverings to Reduce Transmission of Covid-19

- Security as a Normative Issue: Ethical Responsibility and the Copenhagen School

- To What Extent Is ‘Great Power Competition’ A Threat to Global Security?

- Examining and Critiquing the Security–Development Nexus

- To What Extent is the Realist School of IR Theory Useful for Policymakers?