When I was a young undergraduate, there was no shortage of professors who lamented the declining literacy of college students. A common refrain was that students were losing touch with the written word, were frequently neglecting to do their readings, and didn’t understand the fundamentals of how to read. Later, when I began teaching my own courses, I was aghast when I witnessed these same flaws in my own students. In my own undergraduate courses, just getting students to do the readings (any reading) was difficult, to say nothing of reading well.

The problem of declining literacy always seems to be framed as a contemporary one. However, my suspicion is that this is a common message repeated throughout the ages and that we periodically forget that there was never a time when instructors were happy with the quantity and quality of their students’ reading.

The question remains, however: How do we encourage our students to cultivate their own art of reading?

One suggestion is to learn more about our students, where they are in their reading evolution, and to craft messages that encourage them to keep growing as a reader.

When I first started teaching classes at a university and at a technical college, my assumption was that most of the students read at least a few newspaper articles a week. On a whim, I started discussing with students their reading habits during office hours and private sessions. I was surprised at what I discovered. Many students seemed strictly anti-reading. Many relied heavily on cable and talk radio for their news. Other students read habitually but were absorbed largely in a particular genre of interest (in some cases, Young Adult fiction; in other cases, science fiction or fantasy).

It’s important to remember that our time with our students is usually short, so if we want to make an impact on their reading habits, we should think clearly about what our message is and how to communicate it. Knowing where my students were in their reading evolution helped me think of strategies for helping them reach the next stage.

When I was an undergraduate, the best speech I ever received on reading was from an English professor. I remember clearly the final words of that speech, delivered on the final day of class: “What matters even more than what you read is how you read. If you’re not taking notes, writing in the margins, extending the ideas, challenging the ideas, and making them your own, then you’re really depriving yourself of the benefit of reading.”

This was a message by an English professor, delivered to English majors. It hit a lot of the right notes and encouraged me to take many of the habits developed in English class into the world. However, this message would most likely have failed in many of my own classes where many students weren’t reading at all.

A typical short speech in one of my classes often sounds like this:

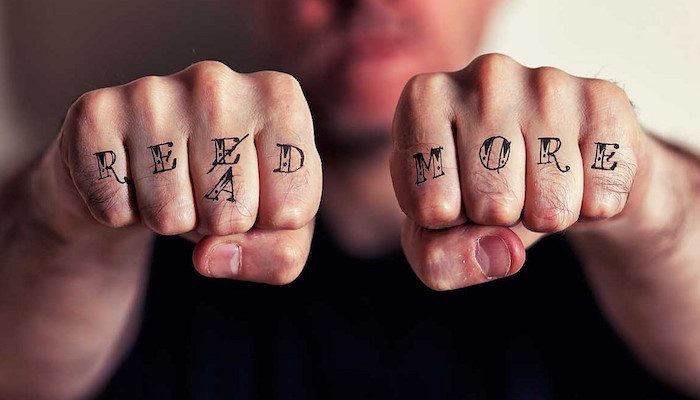

Reading in not just a important skill, it is the important skill. It’s the skill that will make other skills easier to learn. It is the skill that will free your mind from dependence on the opinions of others. It is the skill that is most likely to lead to the kind of lifelong education that will increase your freedom and independence. For this reason, you should never miss an opportunity to improve your reading skills.

For your own student populations, you’ll have to craft your own messages and decide how to deliver them. This message could be as clear and as simple as encouraging them to read outside their comfort zone, to spend some time reading difficult texts to “work out” their reading muscles, or even to just turn off their TV, radios, and electronic devices and read something of substance.

A longer version of this post can be found here.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Getting the Most Out of Class Discussion

- Working with and Supporting Teaching Assistants

- Teaching International Relations as a Liberal Art

- What to Do When You Don’t Like a Topic You Teach?

- Teaching and Learning Professional Skills Through Simulations

- Incorporating Race into Introductory International Relations Courses