This article provides a brief synopsis of the main arguments in Universality, Ethics and International Relations: A Grammatical Reading (Pin-Fat, 2010). In what I hope is a more accessible form than the monograph, I focus on two aspects: (1) the importance of grammatical readings as an ethical and political practice (“doing”) [1] and; (2) also understanding claims to universality as political and ethical practices rather than as the identification of universal foundations (metaphysics).

Rendering the Familiar Unfamiliar

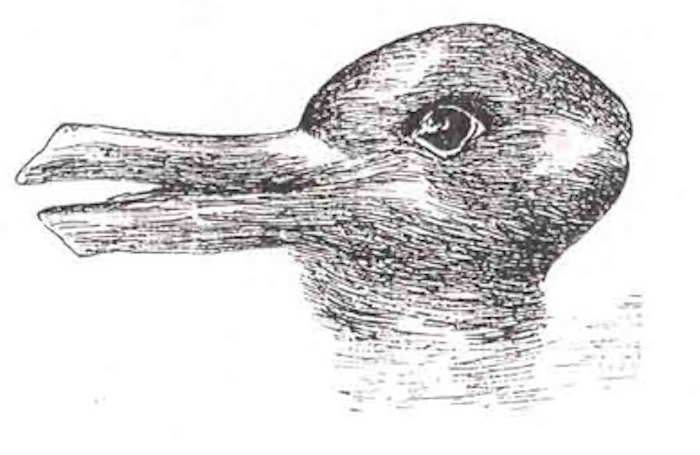

In the image above, what can you see? Do you see a duck or a rabbit? Or, if you’ve seen this image before, perhaps you see a duck-rabbit (Jastrow 1899: 312)?

I want to suggest that understanding the ethical claims to universality in IR is, for heuristic purposes only, similar to looking at the image above. The questions with which I started this section will later become: do you see a hard ontology of universality (a metaphysics of names) or do you see a soft ontology of universality (political and ethical line-drawing practices)? What do you notice when the question is put to you? The inspiration for looking at universality this way comes from the work of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. I propose discussing these questions by thinking through the implications of what is at stake when he said, “The aspects of things which are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity” (Wittgenstein 1958: §129).

For the sake of argument, let’s say that when you looked at the picture above you saw a rabbit. At that point, it meant that the duck was hidden in plain sight. The duck was there the whole time, yet you did not notice it; instead, you recognized the aspects of a rabbit that are familiar to you such as its long ears, the shape of its nose, etc. Until, perhaps, now. Ah-ha! You experience the “dawning” of a new aspect when you see a duck (Wittgenstein 1958: 195). I propose that the hidden “aspects of things which are most important for us” include: (i) that some phenomena are two different “things” at the same time; (ii) that we may come to pictures of “things” with a predilection to see one aspect but not another; (iii) that when we are only able to see one aspect we are blind to the other and its existence; (iv) that important “things” can be hidden in plain sight; (v) that what was once familiar to us (rabbit) can be rendered unfamiliar (duck); [2] (vi) that the dawning of a new aspect is a change in (of) us since it is not the lines of the drawing that have changed; (vii) that what we see can make profound differences to how we relate to our world and the “things” in it—for example, I may want to keep a rabbit as a pet but want a duck to serve as a Sunday roast; and finally, therefore, (viii) if what is at stake are the ways in which we encounter the world and each other, then the above imply that the dawning of a new aspect can itself be a form of political and ethical change. Instigating such change—rendering the familiar unfamiliar—is one of the critical purposes of grammatical readings (Pin-Fat 2010: 4-30). They are designed to provoke the dawning of new aspects by recognizing the political and ethical relevance of aspect blindness.[3] They seek to re-describe the familiar and commonplace as radically different. To say that grammatical readings “leave everything as it is” draws attention to the observation that the lines of the duck-rabbit drawing have not changed (Pin-Fat 2010: 18-23). After a grammatical reading, the lines may well remain, yet how we view them, hopefully, announces a profound change in us; a change in how we go about encountering one another and the world.

(Im)possible Universalism

(Im)possible universalism is a grammatical remark. It describes foundationalist grammars of universality. In Universality, Ethics and International Relations (UEIR) I identify a form of aspect seeing that dominates understandings of universality and offer an account of what produces it. The act of doing so is an attempt to instigate the conditions that make the dawning of a new aspect of universality possible despite being unable to guarantee it.

A grammatical reading of the Realist, communitarian and cosmopolitan language games in international ethics reveal that they all have a commitment to universality rather than particularism.[4] For each, universality is what makes an international ethics possible. Thus, according to them the search for ethics in IR is, necessarily, a search for universality. Without it ethics is impossible.[5]

Seeing “Rabbits”: Familiar Universalisms

UEIR argues that traditional theories of ethics in IR are dominated by the idea that words name objects. It is a view that assumes that language represents, or pictures, reality. Such a view makes engaging with universality a special kind of philosophical and theoretical endeavour. It takes us on a metaphysical search for what universality names and, as such, necessarily becomes a search for its foundations. It digs below the surface of language to find the foundational “objects” that confer meaning.

In IR, the search for universal foundations upon which to ground an international ethics yields different kinds of “object” that universality names; different kinds of universality. The grammatical reading found that the Realist, Morgenthau, grounds his commitment to the universality of the national interest in a Judeo-Christian God. Hence, we have evidence of a divine universalism. In contrast, the cosmopolitan Beitz, grounds his universality on the findings of ideal theory. The most important products of ideal theory are principles of international distributive justice. Hence, there is also a form of ideal universality that is proposed as the foundation for an international ethics in IR. And finally, the communitarian, Walzer, offers a binary universality. For him, what makes ethics possible in global politics are both thick and thin universalisms. Thick universality requires a “legalist paradigm” of ethics. It sees sovereignty and territorial integrity as a way of protecting the way of life that a community’s members have chosen for themselves (Walzer 1977). However, there may be occasions when leaving states to do what they will may be unethical. Thus, his thin universality seeks to name those aspects of moral life that hold for any community no matter what cultural and historical differences there may be between them.[6]

However understood, the thing to note is that each assume that universality identifies features of reality (and being human) that can ground the possibility of ethics in global politics. It is based on a picture of language that generates the idea that there must be a super-order between super-concepts – a “hard” connection between the order of possibilities common to both thought and world (Wittgenstein 1958: §97; Pin-Fat 2010: 9). These universalities therefore, express a hard ontology, i.e. express the nature of reality.[7] In effect, these universalities draw a line around the conditions that make ethics possible. By implication, they are also simultaneously, articulating the conditions that make ethics in global politics impossible. To be clear then, the naming of universals also tells us what ethics needs to exclude as unethical. As such, naming is a line-drawing practice of making distinctions between named phenomena. For example, the distinction between what is (ethically) possible and impossible, permissible and impermissible, desirable and undesirable; the universal moral features of humanity and particularist features which are morally irrelevant;[8] the spaces where ethics can happen and places where it is precluded;[9] and the means of accessing universals vs. approaches that miss the mark.[10] Because all of these aspects are taken to name foundational “objects” below the surface of language, these lines are understood to go deep into the nature of reality. One could say that they carve it up.

“Now, I see a duck!”: An Unfamiliar Universalism hidden in Plain Sight

In this section, I want to argue that (im)possible universalism is hidden in plain sight. It is, so to speak, the duck that is always there even if we have not yet noticed it. “(Im)possible” is a grammatical remark about universalism because it is pointing to workings on the surface of language rather than below it.

For those inspired by Wittgenstein, to make a grammatical remark is to say something about how language use can lead us astray. Wittgenstein famously puts it this way:

“The general form of propositions is: This is how things are.”—That is the kind of proposition one repeats to oneself countless times. One thinks that one is tracing the outline of the thing’s nature over and over again, and one is merely tracing round the frame through which we look at it. A picture held us captive. And we could not get outside it, for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us inexorably (Wittgenstein 1958: §§114-15).

In the case of universality in IR, my claim is that several pictures hold us captive. They are pictures of the subject, pictures of reason and pictures of ethico-political space. There is no space in this short article to review these. Suffice it to say, each picture is an effect of what UEIR calls “metaphysical seduction.” Each claims, in its own terms, to reveal something about the nature of humanity, the acquisition of knowledge and also international political reality as the realm where global ethics takes place. As the purported elements of reality—that together make universality a “real” possibility—they can seduce us into thinking that we are dealing with profound aspects of “Life, the Universe and Everything” that lie beneath the surface of language as the foundations that hold it up.

However, Wittgenstein’s insight is that we have been misled by language. Rather than locating the nature of things “one is merely tracing round the frame through which we look at it”. Accordingly, the frames that inform the universalisms in IR are grammatically constituted. In other words, the grammar of language games (discourses) of ethics in IR determines where the lines of the frame are drawn. Grammar constitutes the inside and outside of the picture frame.[11] UIER is a study of a few of those grammars.

The finding of UIER is that universality can be re-described as (im)possible. That is to say, universality is an effect of what each language games’ grammar configures as possible in relation to what is impossible and vice versa. These configurations are identified as “conditions of possibility and impossibility” of universality. They are co-constitutive, hence “(im)possible” (Pin-Fat 2010: 118-122).

Why does this matter? It matters for several reasons. The first is related to the question of change. Understanding universality as (im)possible means that we are no longer seduced into believing that we are dealing with the nature of reality. The problem with the nature of reality is that it is immutable hence, why I describe it as a “hard” ontology. It is just “how things are”. With this picture of reality, we have no choice but to accept it. It exists independently of us as words are anchored to objects in reality.

In contrast, to describe universality as (im)possible is to notice an unanchored, soft ontology. This is an ontology of reality that is constituted by our practices. The world and everything in it is no longer a given but is a “doing”. As Onuf’s famous book title has it, we now find ourselves in a “world of our making” (2012). That means that we can change it. However, that is not very easy at all. Grammars have a knack of being violently enduring and persistent.

This leads nicely to my second point which is related to ethical responsibility. If the world is of our doing then we can be held responsible for what and how we make, sustain, re-produce, police and reinforce it. This includes what we create as “hard” in our language games such as, universal aspects of humanity, universal features of international political reality and all the lines that such pictures create. This then produces an ethical and political question: how is that “reality” and socio-political rules (grammars) are seemingly so stable and enduring that we are blind to them as soft and only see them as hard? UEIR claims that metaphysical seduction goes some way in identifying how this happens. For as long as we are seduced by a picture of language as naming, we will persist in being blind to the softness of the constituted lines that carve up the world and humanity. The point of UEIR is the observation it is us who carve up the world with hard lines. We make the world hard for as long as we encounter it this way. I suggest that through the continuous repetition and reiteration of practices of representation—picturing—these hard ontologies are held fast. Our practices of drawing lines are political and ethical because the difference between whether they are drawn hard or soft lies in us. It is we who persist in seeing only a rabbit, so to speak, when a duck lies before our very eyes.

In sum, (im)possible universalism points to a form of aspect blindness about universality that is produced by metaphysical seduction. However, if a new aspect of universality as (im)possible is noticed, we are reminded that hard universalism can fail. In a grammatical reading hard, foundationalist, exclusionary claims to universality can “flip” into soft, (im)possible universalities and with it the ever-present possibility of seeing reality as a political and ethical “doing”. (Im)possible universality then demands political and ethical engagement with what we are doing. How does a commitment to a particular picture of universality draw lines? Where are they drawn? Who draws them? Who polices them and how? What are the effects of these lines on people’s lives and subjectivity? What must be assumed to draw them? And most important of all, how do some answers to these questions add up to a set of practices that draw pictures with hard lines, as though they located and mirrored an unquestionable ontological reality?

We might say that a grammatical reading is like seeing the illustration with which we started as a duck-rabbit. It is a reminder that the difference between whether we see a duck or a rabbit lies with us and that this makes a profound difference to how we then live in the world with others. Thus, the relevance of (im)possible universalism for universality, ethics and International Relations is the observation that

“One is unable to notice something – because it is always before one’s eyes . . . And this means: we fail to be struck by what, once seen, is most striking and most powerful” (Wittgenstein1958: §129. My italics).

Notes and References

[1] See also Pin-Fat (2013, 2015, 2016a, 2016b).

[2] I mean ‘“unfamiliar” in the sense of something not being what one originally took it to be.

[3] On “soul blindness”—the failure to acknowledge the humanity of others—see Pin-Fat (2013, 2016a).

[4] This challenges the usual classification of theories of international ethics as divided into universalists and particularists. See the seminal (Brown 1992).

[5] It’s important not to over-generalize this finding. Nevertheless, it holds for Hans J. Morgenthau as a classical Realist (2010: 39-63), Charles R. Beitz as a cosmopolitan (2010: 64-84) and Michael Walzer as a communitarian (2010: 85-110).

[6] The full details of these universalities are found in Pin-Fat (2010: 39-110).

[7] Metaphysics is the attempt to identify and understand the nature of reality.

[8] In UEIR I call what these lines produce “pictures of the subject”.

[9] I call what is produced here “pictures of ethico-political space”.

[10] The postulation of such routes are “pictures of reason”.

[11] For the highly important and seminal study on IR’s fixation on demarcations of inside and outside see R.B. J. Walker (1993).

Brown, Chris. 1992. International Relations Theory: New Normative Approaches. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Jastrow, Joseph. 1899. “The mind’s eye.” Popular Science Monthly 54:299-312.

Onuf, Nicholas Greenwood. 2012. World of Our Making: Rules and Rule in Social Theory and International Relations. Reprint and reissue ed: Routledge. Original edition, 1989. Reprint, 2012.

Pin-Fat, Véronique. 2013. “Cosmopolitanism and the End of Humanity: A Grammatical Reading of Posthumanism.” International Political Sociology 7 (3):241-257.

Pin-Fat, Véronique. 2015. “Cosmopolitanism without foundations.” In Politics and Cosmopolitanism in a Global Age, edited by Sonika Gupta and Sudarsan Padmanabhan. New Delhi and London: Routledge.

Pin-Fat, Véronique. 2016a. “Seeing humanity anew: Grammatically reading liberal cosmopolitanism.” In Re-Grounding Cosmopolitanism: Towards a Post-Foundational Cosmopolitanism, edited by Tamara Caraus and Elena Paris. Abingdon: Routledge.

Pin-Fat, Véronique. 2016b. “Dissolutions of the Self.” In Narrative Global Politics, edited by Elizabeth Dauphinée and Naeem Inayatullah, 25-34. Abingdon: Routledge.

Walker, R.B.J. 1993. Inside/Outside: International Relations as Political Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Walzer, Michael. 1977. Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations. London: Allen Lane.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1958. Philosophical Investigations. Translated by G.E.M. Anscombe. Edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and R. Rhees. 3rd ed. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- ‘Politics of Gratitude’ – Bridging Ontologies: Patronage, Roles, and Emotions

- Recrafting International Relations through Relationality

- Assessing the Impact of Hybrid Threats on Ontological Security via Entanglement

- Tagore’s Ideas on Universalism, Cultural Distinction, and the Global

- Opinion – The Limits of Humanist Ethics in the Anthropocene

- Coronavirus, Resilience and the Limits of Rationalist Universalism