INTRODUCTION

Research Question

The aim of this research is to analyze the foreign policy of the Russian Federation under President Vladimir Putin, focusing on the various changes that took place in Russian foreign policy since Vladimir Putin became president in 1999, and specifically on the annexation of Crimea and the Russian military involvement in the Syrian war. It sets out to explain these changes and classify them through a theoretical model developed by Charles F. Hermann in his article ‘Changing Course: When Governments Choose to Redirect Foreign Policy’, attempting to answer the following question: which are the most influential factors in shaping Russia’s foreign policy under Putin?

The paper holds that there is a mix of internal causes and exogenous factors determining the course of Russian foreign policy. It is not sufficient to focus on foreign policy because foreign policy is a mirror of domestic policy and it is driven by it. The most important of these factors, both domestic and external, have been analyzed and compared as to conclude which exert most weight. Furthermore, this paper’s aim is also to identify how much power does President Vladimir Putin exercise in the Russian political context, with the objective of understanding how influential he, as an individual, is in shaping Russia’s foreign policy.

Research Objectives

This study aims to give a different focus to the much-discussed subject of Russian foreign policy. Indeed, while a lot has been written on this topic, an investigation that explains changes in Russian foreign policy by identifying its driving forces through the theoretical model developed by Charles Hermann, is a new approach.

A second objective is to apply Hermann’s theory to an existing context in international relations. Hermann developed a model, based on four agents, to be used to analyze and explain changes in countries’ foreign policies. This paper applies Hermann’s theory specifically to the scenario of Russian politics.

Finally, this dissertation wants to shed light on which are the real driving forces of Russian foreign policy, because in Western research on this subject external events often tend to be identified as more influential variables in shaping Russian foreign policy than are domestic occurrences.

METHODOLOGY

“Theories are beacons, lenses or filters that direct us to what, according to the theory, is essential for understanding some part of the world.” – Donnelly, 2005.

Various theories of international relations can be helpful in the analysis of a country’s foreign policy as they provide us with schemes and frameworks upon which one can try and fit the actions of a country, thus classifying them as one or another kind of foreign policy. In short, theories allow us to label a country’s foreign policy. Although realism and liberalism are among the main theoretical traditions in international relations used to interpret foreign policies, and albeit some characteristics of realist theory are clearly reflected in Russia’s behavior, neither of these two approaches is the most appropriate to undertaking an analysis of Russian foreign policy.

A theoretical model proposed by Charles F. Hermann, on the other hand, does seem to provide the most appropriate starting basis from which to try and decode Russian foreign policy and foreign policy changes under the administration of President Vladimir Putin. Hermann’s schemes is a tool aimed at understanding what causes governments to redirect their foreign policies; as such, it suits this analysis, given that Russia’s foreign policy experienced several abrupt redirections in its recent history. Some of these changes, of course, coincided with a radical modification of the country’s political system, some corresponded with changes in administration, and some – those that interest us the most – took place under an existing administration, specifically the one of Vladimir Putin. Hermann created a theoretical framework, a scheme whose objective is to interpret those situations in which governments decide to change the direction of their foreign policies.

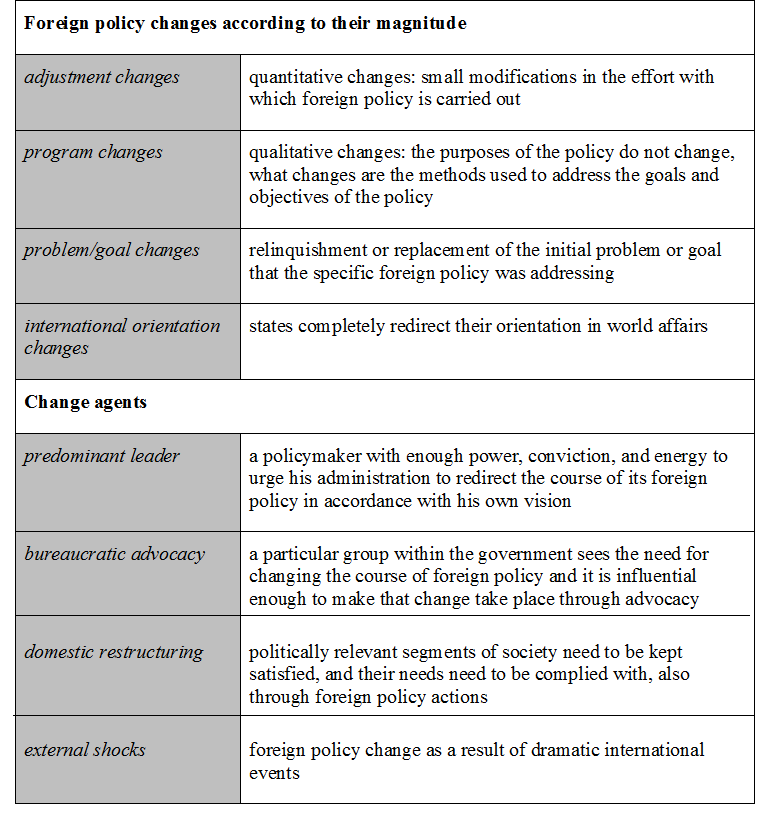

Firstly, Hermann (1990, p.5-6) classified foreign policy changes according to their magnitude and divided them into adjustment changes, program changes, problem/goal changes, and international orientation changes. Adjustment changes are quantitative changes: small modifications in the effort with which foreign policy is carried out, or refinements of the targets of that particular policy. Under such changes the main purposes of the policy remain unchanged, so does what is done, and how it is done. Program changes are qualitative changes: in this case too, the purposes of the policy do not change, what changes are the methods used to address the goals and objectives of the policy; in others words, what is done and how it is done does change. Problem/Goal changes see the relinquishment or replacement of the initial problem or goal that the specific foreign policy was addressing. At this stage, the purposes of the policy are replaced. International orientation changes are the most extreme kind of foreign policy alterations: in such events, states completely redirect their approach to world affairs. There is a fundamental shift in the country’s international activities and role. According to Hermann, while adjustment changes do not represent major foreign policy redirections, the other three kinds of change do.

Secondly, Hermann (1990, pp.11-12) identified four ‘change agents’ or sources of change; that is, the causes behind a government’s decision to redirect its foreign policy. Change agents are: predominant leader, bureaucratic advocacy, domestic restructuring, and external shocks. When a policymaker, usually the head of government, has enough power, conviction, and energy to urge his administration to redirect the course of its foreign policy in accordance with the policymaker’s own vision, one can talk of predominant leader-driven change. Bureaucratic advocacy change happens when a particular group within the government sees the need for changing the course of foreign policy and it is influential enough to make that change take place through advocacy. Domestic restructuring as an agent of change is possible because any government needs the support and legitimation of the most politically relevant segments of society for it to govern effectively. When these elites either change in their composition or alter their views on foreign policy, they can cause the policy to be redirected. Foreign policy change can also be the result of dramatic international events. When these events’ visibility and their impact on a government are large, they can spark major foreign policy changes. In this scenario, one can talk of external shocks as a source of policy change.

Table 1. Hermann’s Scheme

Clearly, these agents of foreign policy change are not mutually exclusive, and, for a foreign policy redirection to happen, there often needs to be an interaction between some or all of these sources of change. For instance, an external shock could activate a leader-driven initiative to change foreign policy course. Finally, change always seems to stem from failure. This means that a redirection of foreign policy is dictated by the realization that the actual policy is not properly addressing the problems it had set out to resolve, or that it is not achieving the goals it was meant to reach.

Hermann’s model will accompany us throughout this paper as an assistance tool in our assessment of Russian foreign policy under President Vladimir Putin. The real-life case of Russia will be juxtaposed to Hermann’s theoretical model to allow for a guided, less dispersive investigation. The specificity and practicality of Hermann’s model are what make it a more attractive instrument for a study of Russia’s foreign policy than are the realist and liberalist theoretical frameworks.

Of course, labeling events as black or white in social sciences is never a good idea, as grey tends to prevail in this imperfect science. Therefore, to claim that a country’s foreign policy falls exactly within a theoretical framework – in this case, Russian foreign policy within Hermann’s model – would mean stretching reality. However, theories do represent extremely useful tools when trying to order and simplify extremely complex matters. The readers are therefore invited to keep in mind that, whenever I have applied Hermann’s theory to the realities of Russian foreign policy in this paper, I have done so simply in order to make an extremely complex and multifaceted theme more orderly and easier to comprehend. My application of Hermann’s theory to the realities of Russian foreign policy is in no way an empirical truth, but rather my choice of a theoretical approach that I regard as the most appropriate to explaining Russian foreign policy.

CHAPTER 1. Persistent Foreign Policy Themes (Russia’s Core National Interests)

Before setting out to analyse which changes have taken place in recent Russian foreign policy, it is wise to take a look at which have been the recurring priorities in Russian foreign policy since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Having a clear vision of Russia’s main interests since the country’s birth will make it easier to evaluate whether the changes that take place under Putin amount to radical turnarounds in Russian foreign policy, or if they are simply adaptations of decades-long goals to the realities of today.

According to Margot Light (2015), several themes that embody Russia’s main foreign policy interests and goals have remained consistent since the birth of the post-soviet Russian state. These topics were customarily repeated in most foreign policy and security documents since the first Foreign Policy Concept was issued in 1993. The most persistent one among these themes is Russia’s prioritization of its relations with the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which is unfailingly listed as the most important regional priority for Russia. More generally, as Lukyanov (2016, p.35) wrote, Russia has historically considered Central Asia as its zone of influence, a chessboard where Russia would play to dominate. Russia’s territory is mostly composed of vast flat plains, which has made the country vulnerable to external invasions by enemies attempting to conquer it. As a consequence, Russia has always felt the need to create buffer zones around its core, expanding the space around it, to make an invasion more difficult.

This kind of strategic thinking might seem outdated, belonging to the past. However, it has influenced Russian policymakers until the end of the 20th century, and into the 21st. This century is not likely to see any ground invasion of Russia by a foreign enemy. Nonetheless, the Kremlin is concerned with a more sophisticated kind of invasion that might take place if the CIS were to become westernized: it could eventually influence the Russian population and bring about regime change in Russia. That is why the CIS, the former Soviet possessions, are so important to Russia’s administration; it wants them under its influence because they represent a buffer to protect its core. Russian leaders, including the more moderated ones like Medvedev, have unfailingly considered the post-Soviet space as their primary foreign policy priority, a zone of privileged interests (Kuchins & Zevelev, 2012, p.156).

This brings me to another pillar of Russian foreign policy: its opposition to NATO’s eastward expansion. Although Russia has at times been much closer to the West and NATO than it is today – to the point of even considering joining the organization – one must notice that the threat posed to Russia’s security by NATO’s eastward enlargement in ‘the immediate proximity of Russian borders’ has been persistently mentioned in official documents (National Security Concept, 2000). Lukyanov (2016, p.32-33) reminds us of how, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the West started to spread democracy to the world. At times it did so peacefully; however, elsewhere in the world, the West opted to resolve to military force to get rebellious countries to abide by the rules of the Western-established international order. Since the Gulf War, the West has resorted to force, either through NATO or individual state actions, more and more often. It did so in 1999, when it bombed Serbia, a close Russian ally in Europe, to support the secession of Kosovo. Following that operation, NATO or some of its members have engaged in military interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, bringing about regime change in all three occasions. Again Lukyanov (2016, p.33), as well as Russian political analyst Sergei Karaganov (2011), hold that from a Russian perspective NATO has transformed from the purely defensive organization it was during the cold war, into an offensive organization: it is objectively difficult to contradict them. A more aggressive NATO has been incorporating countries that were former Soviet members (i.e. Baltic states and Poland) which have now become increasingly anti-Russian and that, most importantly, previously formed a buffer zone between NATO and Russia. Therefore, from a Russian perspective, it becomes clear that NATO’s eastward expansion into its area of influence and buffer zones represents a significant threat. Specifically, if Ukraine were to join NATO, Russia would share a 2000 kilometers border with NATO, something it finds unacceptable.

Partly as a consequence of Western military interventions to bring regime change and the establishment of democracy, Russia has also always been a staunch defender of sovereignty, territorial integrity, and international law in general (Light, 2015). In other words, Russia has persistently defended its right to sovereignty and independence and has been critical of Western actions of interference in the domestic affairs of other states. It has also expressed a commitment to defend the norms of international law against unilateral or multilateral attempts on the part of other countries to change them. Putin’s war in Georgia and annexation of Crimea broke that commitment. These two events represented abrupt shifts in the foreign policy of the Russian Federation. Indeed, Chapter 4.1 is dedicated to explaining the reasons behind Putin’s decision to annex Crimea, disregarding Russia’s long-held commitment to the respect of international law.

Another threat to Russian security that was regularly included in documents on foreign and security policy is represented by the deployment, on the part of other countries, of ballistic missile defence systems, particularly when these are close to Russia’s borders. Russia holds that such systems undermine regional and global stability and give an unfair strategic advantage to the country or countries adopting them. The resistance to the establishment of a missile defence system in Europe can thus be identified as a fourth persistent theme in Russian foreign policy, together with the three mentioned above: (1) importance of its sphere of influence on the CIS; (2) opposition to NATO’s eastward expansion; and (3) a defence of sovereignty, territorial integrity, and international law.

Two other recurring themes at the core of Russian foreign policy, which are both inextricably connected to the ones just described, are the call for a multipolar world, and the achievement and consolidation, by Russia, of its great power status.

Since the year 2000, and following the 1999 NATO military operation against Serbia, a call for a multipolar world where international problems are resolved through multilateral cooperation as opposed to unilateral actions and unipolarity has been a constant in Russian foreign policy concepts. However, what can be considered as the paramount core element of Russian foreign policy – one that has achieved even more importance under Putin – has been that of first retrieving, and then consolidating, its status of great power, derzhavnost. In the words of Putin himself “we will strive to be leaders” (Putin apud Light, 2015, p.16). Russia has therefore always considered itself an equal to the United States and Europe and it has no intention of being led by them; it has always defended its position as an independent strategic player (Carnegie Moscow Center, 2012). Indeed, as typical of most great powers, Russia has historically considered itself an exceptional country with a special mission. This has made Russians very proud people, and it also caused them to be highly resentful to the West whenever they felt like it was disregarding Russia’s exceptionalism. This sense of uniqueness and of being on a mission has taken on several different hats throughout time: from the third Rome to the pan-Slavic kingdom, from being the center of world Communism to today’s Eurasianism (Kotkin, 2016, p.3).

CHAPTER 2. Vladimir Putin: the Predominant Leader

“Russia’s political system is tsarist, and Putin is a present-day absolute monarch.” – Dmitri Trenin, 2015.

Before setting out to explain how (and for one to be able to understand why) Russian foreign policy has changed so frequently since Putin became president, it is necessary to understand that foreign policy in Russia is currently decided by Putin himself. The reasons for such an extended power being concentrated in the hands of a single man are primarily historical. In fact, as Kotkin (2016, p.4) rightly noted, and as mentioned in Chapter 1, one of the main historical drivers of Russian foreign policy has been its struggle to be (and be recognized as) a great power. Throughout the centuries, Russians felt that – because the world is extremely dangerous, and because the country’s geography offers no natural defences – the only way that Russia had to guarantee its security was by having a strong state capable of resorting to force to protect itself and its interests. The unintended and paradoxical consequence of such effort has been, over and over again, the weakening of the Nation’s institutions and the establishment of a personalistic rule. During the Romanov years, under Lenin, Stalin, and up to this day, personalistic rule has thus been the norm in Russia, with considerable amounts of power concentrated in the hands of one individual. This has led to decision-making, including in foreign policy, often being capricious.

The control over foreign policy in the hands of one leader has remained true in post-Soviet Russia, and it was legitimated by the Constitution. Articles 80 and 85 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation give the President the authority to govern the country’s foreign policy (Constitution of the Russian Federation, 1993). However, it cannot be ignored that – differently from the Russian leaders who preceded him – Putin can exercise such an enormous amount of personal power also, and to a great extent, because he was able to win over the trust and the love of most ordinary Russians. Indeed, one shouldn’t forget that the situation in Russia following the collapse of the Soviet Union was a dramatic one, marked by economic depression, street crime, and an extremely violent fight among the oligarchs for winning control of former Soviet assets that were being privatized (Laqueur, 2015). Richard Sawka (2008; p.2) defined that period as “the greatest economic depression in peace time in modern world history”. Since Putin came to power, by exploiting rising energy prices, but also thanks to his personal skills, he was able to re-establish a functioning state. The President promised he would put an end to the chaos and the corruption that had flourished under Yeltsin, and that he would restore Russia’s rightful place as an independent great power (Braithwaite, 2015). Essentially, Putin entered an unofficial ‘contract’ with the Russian people according to which, in exchange for almost uncontested authority, he would restore security and economic prosperity, and give the population reasons to be proud of their country, by bringing it back to being an internationally influential player.

Dmitri Trenin (2015, p. 34) is among the many eminences backing the argument that Vladimir Putin is the sole decision maker when it comes to foreign and security policy. Trenin confirms that Putin’s decisions in foreign policy are based on what he believes are Russia’s national interests and on his philosophical interpretations of right and wrong. Consequently, the President’s views on international affairs, and on what ought to be Russia’s role and status in the world, are of the utmost importance. Of course, the fact that so much power is concentrated in the hands of one person (Hermann’s predominant leader) means that, as suggested in Chapter 3, any person or any factor that ends up exerting an influence on the predominant leader will also have a direct impact on his views on foreign policy.

However, this doesn’t change the fact that the predominant leader remains the most relevant of all agents of foreign policy change. In fact, influence groups and elites (heinafter bureaucratic advocacy), external events (external shocks), and domestic developments (domestic restructuring) are all relevant drivers of foreign policy change in as much as they affect the views of the real decision-maker: the predominant leader, Vladimir Putin. A more detailed analysis of how bureaucratic advocacy, domestic restructuring, and external shocks played a role in shaping the changes in Russian foreign that took place in Putin’s first and second terms is to be found in the next chapters.

Fiona Hill (2015, pp.45-50), senior fellow at Brookings Institution’s Foreign Policy program, while supporting Trenin’s view that Putin is the only decider on relevant matters of Russian foreign policy, goes even further. Indeed, she holds that Putin’s character is composed of six identities he developed because of various experiences from his past personal and professional life: statist, history man, survivalist, outsider, free marketer, and case officer. These six identities, she argues, play a significant role in shaping the foreign policy priorities and goals that Putin has identified for Russia, as well as the methods he chooses to implement his policies and reach those goals. The fact that the President’s personal views on foreign affairs, shaped by his life experiences, become the pillars of Russian foreign policy, is the utmost demonstration of the fact that, in the context of Russian politics, the predominant leader is undeniably the most determinant agent of foreign policy change.

The rest of this dissertation looks at how the three other agents of change (bureaucratic advocacy, external shocks, and domestic restructuring) contributed to causing foreign policy shifts in Putin’s first and second terms in office, and how they are currently contributing to changes in his third term. However, the reader should always keep in mind that the three above mentioned agents of change were, at all times during Putin’s three terms as president, and even during his term as prime minister, influencing the predominant leader.

CHAPTER 3. Russian Foreign Policy Changes under Putin: 1st and 2nd Governments

Having described the incredible amount of personal power Vladimir Putin exerts in Russia, it is time to proceed and analyse the changes in foreign policy that took place under his three terms as president, and during his tenure as prime minister. Indeed, many authors have argued that even during Medvedev’s presidency, it was Vladimir Putin who held the reins of the Russian state (Pavlovsky apud Hearst, 2012; Neef & Schepp, 2011; Bidder, 2011). After analysing these foreign policy changes, and having identified which change agents (bureaucratic advocacy, external shocks, domestic restructuring) played a role in making policy changes happen, this chapter argues that the current stance of Russian foreign policy is not a sudden tailspin (international reorientation), although it may seem so. Instead, it’s the final, most extreme section of a process of change in Russia’s foreign policy stance that began even before Putin came to power, and that got much stronger under his rule.

Of course, a government undertaking a different foreign policy path is not something unusual, and other Russian and Soviet leaders had done so before. However, change has been such a continuous feature in Putin’s tenures as president that one simply cannot set out to explain his foreign policy without keeping change in mind. Although one might think that changes are a peculiarity of Putin’s third term, such line of thought would be a misinterpretation of reality. In fact, Vladimir Putin already showed a surprisingly high tendency to changing his foreign policy during his first two terms as president. Taking a closer look at these precedents, and understanding what motivated them, will help us better comprehend current foreign policy changes and to consider whether or not they are following a logical, historical pattern. I will make use of Charles Hermann’s model to first consider the extent of the changes that took place during Putin’s first two terms and then to explain how bureaucratic advocacy, domestic restructuring, and external shocks contributed to shaping the foreign policy decision-making of the predominant leader.

Professor Dina Rome Spechler (2010) comes in handy here, since she identified four starkly different phases in Putin’s foreign policy during his first two tenures, and gave her explanation as to why such changes occurred. Her analysis looked specifically at the Russian foreign policy approach to the West and particularly the United States. Such an approach, while limited in scope, is an appropriate tool to use in the context of this study since I am mostly concerned with the changes in posture that Russia has recently been taking with respect to the West. After all, as Kuchins and Zevelev (2012, p.152) have argued, “for most policymakers and elites in Moscow, old habits of measuring success or failure through a U.S.-centric prism have endured”. I will thus briefly summarize Spechler’s four phases of Putin’s foreign policy and – through Hermann’s model – I will classify them by magnitude and identify the change agents that played a critical role in these contexts.

The first phase (2000-2001) of Putin’s foreign policy was characterized by mistrust of, as well as antagonism towards, the West. The animosity between Russia and the West stemmed from several controversies: the West’s role in the CIS and the uncertain future of the Baltic countries; disagreements regarding energy routes; and troubles concerning the Strategic arms Reduction Treaty (START). Putin was cultivating relations with China, Cuba, and North Korea, as well as with Iraq and Iran, which were all countries of extreme concern to the West. At the same time, he was denouncing most US actions that somehow had an effect on Russia. For instance, he was especially critical of the US’ intended withdrawal form the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABMT) and of its plan to build a national missile defence system. The US military intervention in Yugoslavia and the talks about NATO’s expansion to Eastern Europe were also issues that particularly irritated his administration at that time (Spechler, 2010, p. 41).

The terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001 on the United States coincided with the beginning of the second phase (2001-2002) of Putin’s foreign policy. It was a complete tailspin with respect to the first one. A change so radical that it could well have appeared as the most extreme form of change in Hermann’s model: an international reorientation (although, as explained further down, it wasn’t). Russia went from opposing the US and the West in almost every respect, to willingly engaging with them in a relationship of partnership and trust. Excitement was so high that then-Russian foreign minister Igor Ivanov claimed the emergence of a “new world order” (Ivanov apud Spechler, 2010, p.37). In fact, from that day onwards, and for about one year, Putin’s Russia was cooperating with the United States and the West on a wide array of issues. It is not an exaggeration to say that that was one of the most pro-Western stances in Russian history. Putin immediately declared that Russia would give full support to the US in its war on terror, enthusiastically announcing that Russia would give military aid and share intelligence to erase Al-Qaeda off the map. Former Soviet military bases in Central Asia were made available for use by US troops. The Putin administration went so far as declaring that Central Asia hadn’t been considered as an area of exclusive Russian influence, something that clearly contradicted one of the core historical principles of Russian foreign policy. Even more astonishing was the fact that what only one year earlier had been a matter of enormous bilateral tensions – the US announcing its withdrawal from the ABMT – was now regarded as an issue of little concern that would not jeopardize the two countries’ reciprocal trust. Russia also abandoned former threats that it would have responded asymmetrically to a US deployment of a missile defence system. Putin himself declared that he believed that “the decision taken by the President of the United States does not pose a threat to the national security of the Russian Federation” (Putin, 2001). However, Putin’s most dramatic shift, which broke drastically not only with the foreign policy line he had previously followed, but also with that of his predecessors, was his repositioning on another issue which, like Russia’s influence on the CIS, had long been regarded as one of the core elements and biggest concerns of Russia’s foreign policy: NATO’s eastward expansion. Indeed, not only did Putin reconsider Russia’s decades-long opposition to the expansion of the Western military alliance into Russia’s backyard; he even claimed that Russia was keen to strengthen its relationship with NATO and possibly even to consider joining it as a member state (Spechler, 2010, pp. 36-37).

However, Spechler (2010, p.37) points out that this love affair with the West was short-lived. When the US announced its plan to go to war with Iraq, Putin publicly opposed the Iraq mission and the US as a whole. He claimed Russia would veto any US-sponsored Security Council resolution that would authorize the use of force against Saddam Hussein. Not even one year had elapsed since the beginning of the second phase, and there it was already, the third phase (2002-2003), a renewed period of Russian bitterness towards the US and the West. Once again, in a one-year span, Russia was undertaking what seemed to be another international orientation change in its foreign policy. However, in this case too and as clarified below, it was only apparently an international reorientation.

The bitterness was soon transformed into outright hostility. The fourth phase (2004-2008) corresponded to Putin’s second tenure as president, and it was characterized by the Russian extension of its antagonism beyond the US to include NATO and the European Union. By the end of it, when Putin became prime minister, the relations between Russia and the West were as compromised as they had been during the last ten years of the Cold War. Indeed, that period saw Russia suspending its commitment to, or considering withdrawing from post-Cold War East-West security institutions such as the Treaty on Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) and the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. The latter would have happened in response to the US’s stated intention of deploying missile defence systems in Poland and the Czech Republic. Moscow also started testing and displaying offensive weapons intended to penetrate a national missile defence system the US had been testing. Unsurprisingly, it was the US that attracted most of Russia’s criticism. According to Spechler (2010, pp.37-38) Putin publicly accused the US of intending to create an internal division in Europe, undermining international institutions, and instigating a nuclear arms race. Russia also began denouncing Western policies on a wider array of issues. The Baltic countries went back to being a contentious issue as Russia claimed that if NATO were to extend to those countries, unspecified actions of retaliation would follow. Spechler also argued that when the pro-democracy colour revolutions began in countries like Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan, Putin started talking about a Western plan to install friendly regimes in the CIS to surround Russia and ultimately bring about regime change in the country itself. He labelled human rights and pro-democracy Russian NGOs as instruments used by Western governments to channel funds used to influence Russian politics. As a response to these alleged machinations, Putin took several other actions to eliminate Western presence in and influence on the CIS. Countries in the region that had relations of any kind with the West were somehow punished by Russia. The price Ukraine had to pay to purchase Russian gas was increased dramatically, and the supply cut off twice when Ukraine had trouble paying the bills. Georgia was targeted military in more than one occasion after it declared its intention of joining NATO. Military relations with pro-Russian regimes in the CIS and with China were intensified. The foreign policy change that took place from phase three to four was a good representation of Hermann’s changes in magnitude of a country’s foreign policy: adjustment change and program change. In fact, while the purpose of Russian foreign policy did not change, the extent of Russia’s efforts and the instruments that Russia chose to achieve its foreign policy goal did change.

The apparently radical foreign policy changes that took place between phase one and two, and phase two and three of Putin’s foreign policy – which, as mentioned before, might have appeared to be international reorientation changes – were, too, only program changes. Even when he considered joining NATO as a member state, and when he offered help to the US in the war on terror and gave the US access to former soviet military basis, Putin was trying a different approach to achieve his goal of making Russia a great power again. It was yet another attempt to join in with the West as equals; two great powers that would shape and protect the world while respecting each other’s vital interests. When Putin understood that the West wouldn’t accept Russia as its equal, it adopted yet another program change and went back to a more distant, wary, assertive approach. A more detailed explanation of Russia’s decades-long struggle to reaffirm its great power status is provided in Chapter 4.

The driving forces behind the foreign policy changes that took place during the four phases were various, and it is relevant to go over each of them because they are still the driving forces behind the changes that are occurring in Putin’s third term. Even though, as explained later, the particular weight that each force exerts is different today than it was during Putin’s first and second term. For instance, domestic restructuring – which did not play particularly relevant a role in shaping the foreign policy changes that occurred during the first two terms – has become one of the main driving forces in Putin’s current foreign policy.

The second section of Hermann’s model, the one dealing with the agents of change, serves here as a scheme to rationalize such changes. I will henceforth demonstrate how all of Hermann’s change agents played a crucial role in shaping the changes in Putin’s foreign policy that occurred throughout the four phases. More specifically, bureaucratic advocacy, domestic restructuring, and external shocks influenced a predominant leader – in this case, Vladimir Putin – and thus significantly contributed to shaping that leader’s foreign policy decision-making.

3.1. Bureaucratic Advocacy’s Influence on the Predominant Leader

Within the Russian political context, there are pre-formed approaches to foreign policy, as well as influential groups pushing for individual policies, which can both be considered forms of bureaucratic advocacy because Vladimir Putin is exposed to them and they can influence his views. Spechler (2010, pp.38-45) wrote of five different approaches to foreign policy – the liberal, the nationalist, the great power activist, the realist, and the assertivist – backed by five sections of the Russian elite, that had an influence on President Vladimir Putin, at different times during his presidencies, and were thus partly responsible for the abovementioned changes in foreign policy. The changes these elites contributed to causing fit in the category of bureaucratic advocacy changes as defined by Charles Hermann; that is changes in foreign policy stemming from advocacy groups within the government that are influential enough to have their voices heard. Adapting Hermann’s definition to the Russian case, one should speak of elites in general, rather than of groups within the government since not all of these elite groups belong to the government, despite most of them do.

Two other authors, Kuchins and Zevelev (2012), offered their classification of the various elites and groups whose views on foreign policy have (or had) influence in shaping the actual policies. The three approaches they identified are the pro-Western liberals, the great power balancers, and the nationalists. Although their classification does not exactly mirror Spechler’s, the two models present significant similarities. However, it must be specified that the Western liberal approach, which was followed by the government of President Boris Yeltsin until 1993 – and whose core idea was that Russia ought to “subordinate its foreign policy goals to those of the West” and aspire to become a fully Western nation – has since lost traction in Russian politics and thus did not exert significant influence on Vladimir Putin.

From 1993 until 2003 the great power balancers approach has been the most influential among the various viewpoints on foreign policy. Evgeniy Primakov was the frontman of this movement, which strived to reassert Russia’s status as an independent great power. This vision of the world largely coincides with Vladimir Putin’s, who adopted it and made it his own at least until the end of his first term. It can thus be argued that the great power balancers are an example of bureaucratic advocacy affecting a predominant leader.

Since 2003 two external shocks – actions by the Bush administration, and the rising oil prices that accelerated Russia’s economic growth – caused Putin to shift, between his first and second term (phase three to four) from a power balancers to a nationalist approach, one characterized by a resolute opposition to the US and the West. Ever since, nationalism has been the most influential of the bureaucratic advocacy approaches, and all the representatives of other visions have understood that, in order to survive, they had to adopt some elements of nationalism (Kuchins & Zevelev, 2012, pp. 147-160).

The relevant point for the purpose of this essay is that the foreign policy views, as well as the interests, of various influential groups (such as the oligarchs, or the secret service), think tanks, political parties, and experts do play a role in shaping Russian foreign policy because the predominant leader is exposed to them. At times the bureaucratic advocacy might actually be capable of influencing him directly: for instance, powerful arms industry oligarchs (who can leverage on their being an important source of revenues for the country) or army officials that have an interest in Russia engaging in military operations, might influence Putin in a particular direction. However, these approaches and groups are not stronger than Putin’s will and don’t dominate his mind.

Another demonstration of the fact that bureaucratic advocacy plays a relevant role in causing foreign policy change is provided by Pavlovsky (2016, p.12). He argues that because Putin is a predominant leader with a great deal of power, he often limits himself to simply accepting or refusing proposals that were presented to him by advisors. His decision-making is defined as reactive. Pavlovsky claims that Russia’s actions “rarely stem from Kremlin directives but rather result from a sort of contest among Kremlin-related groups, each seeking to prove its loyalty”. He refers to this political machinery as sistema and holds that the fight among various groups to obtain Putin’s favor and approval can be extremely dangerous. The murder of opposition leader Boris Nemtsov in 2015, as well as the assassinations, in 2006, of journalist Anna Politkovskaya and former Russian intelligence officer Alexander Litvinenko – both high-profile Kremlin opponents – were most likely demonstrations of loyalty to Vladimir Putin by people trying to prove their worth, rather than direct orders from the President himself. Both Pavlovsky (2016, p.11) and Ledeneva (2015) argue that sistema had existed in Russia prior to the coming to power of Vladimir Putin, and will outlive him. Dmitri Trenin (2015, p.34) too, while recognizing that Putin is alone in making the most important foreign policy decisions, states that the influence of top government bureaucrats does play a role. A whole dissertation could be written on this issue, studying who are the people in Putin’s closest circle. Future research could attempt to test the actual extent of the influence the bureaucratic advocacy exerts on the predominant leader. However, this is too broad and complicated a subject, also due to a lack of accessible information, to be treated in detail in this dissertation.

3.2. Domestic Restructuring’s Influence on the Predominant Leader

Richard Sawka (2008, p.241) has argued that, while foreign and domestic policies are usually highly interconnected, in Putin’s Russia there has been a collapse of foreign policy into domestic constraints. SciencesPo Professor Marie Mendras (2015, p.81) wrote that the colour revolutions were the cause of growing concern, within the Kremlin, that if those countries got democratized Russian society could also get contaminated by democracy. While this cannot be considered as a pure domestic restructuring because at the time of the colour revolutions Russia was growing economically and Putin enjoyed strong domestic support, it can be argued that the fear that the revolutions could potentially trigger a domestic restructuring in the near future did bring Putin to undertake a more aggressive stance towards the West in his foreign policy. Dmitri Trenin (2015, p.34) argued that, despite Putin being a strongman leader, he does have to keep into account the way private citizens feel. It was in Putin’s third term when the economic crisis hit hard, and Russians started feeling dissatisfied with the Putin administration and staged protests in the main Russian cities, that domestic restructuring became a major change agent in foreign policy. More on this is to be found in Chapter 5, which is entirely dedicated to domestic restructuring as one of the two main forces driving foreign policy change, together with the predominant leader.

3.3. External Shocks’ Influence on the Predominant Leader

Spechler (2010) identified external events as partly responsible for changing Putin’s foreign policy during the four phases. It is pretty intuitive to understand that those external events that contributed to causing foreign policy change fall well within Hermann’s category of external shocks as agents of change. Although the term shock has a negative connotation, one would be mistaken to think that they necessarily lead to a more aggressive or inimical foreign policy posture. In fact, the terrorist attacks of 9/11 paradoxically offered a good opportunity for Putin to change his foreign policy from a nationalist to a realist approach (phase one to phase two) because they highlighted the terrible power of an enemy (i.e. Al-Qaeda) that the West and Russia had in common. Russia could exploit its favourable geographical position and military strength to offer help to the US in its war on terror, hoping that the US would reciprocate by respecting Russian interests and politics.

The US’ decision to wage war on Iraq in 2003 can certainly be regarded as another external shock and Spechler considered it as an event that was largely responsible for changing Russia’s foreign policy from a realist to a great power activist status (phase two to phase three). Indeed, the action by the US openly disregarded one of Russia’s core foreign policy principles: the respect for international law; specifically, for a country’s right to sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity. The US’ war on Iraq was a flagrant violation of the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and it was illegal under international law, since it was conducted without the authorization of the UN Security Council.

The pro-democracy uprisings named ‘colour revolutions’ that took place in the former Soviet territories of Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan from 2003 to 2005 also undoubtedly amounted to external shocks. As mentioned in Chapter 1, the CIS has historically been a priority for Russia, which considers it its ‘zone of influence’. Consequently, to see democratic, anti-Russian parties achieving power in those countries must have been a grave concern for the Kremlin. However, a much greater external shock was the fact that the West unwisely admitted fomenting and supporting the colour revolutions. In fact, then-US President George W. Bush had announced that the then recently created Active Response Corps, whose goal was to support pro-democracy groups achieve their objectives, would soon have had an opportunity to operate in the context of other colour revolutions in the post-Soviet space (Bush, 2005). Putin saw this as an outright attempt by the West to surround Russia with pro-democratic regimes with the ultimate goal of causing regime change in Russia (Spechler, 2010, p. 44).

As explained in more detail in Chapter 5, one of the main drivers of Putin’s foreign policy today is the maintenance and protection of his regime. It is intuitive to comprehend that a public declaration by the US of wanting to facilitate the spreading of democracy to the Post-soviet region represented one of the most direct threats to the Russian regime’s survival.

Several other actions by the Bush administration caused grave disillusionment to Putin: its efforts to admit Georgia and Ukraine into NATO, its announcement in January 2007 that it would deploy a missile defence system to Poland and the Czech Republic, and its uninhibited support of Georgia before and immediately after the conflict with Russia. All these amounted to external shocks, which unsettled Putin and contributed to shifting his foreign policy towards a more anti-Western, assertive stance (Kuchins & Zevelev, 2012, p.156). In short, the colour revolutions, the West support of them, and the US’ plan to deploy missile defence systems in Eastern Europe were all external shocks which contributed to shifting Russia’s foreign policy from a great power activist to a more aggressive, nationalist and assertivist approach (phase three to phase four).

However, in Chapter 5 I argue that, while external shocks played a more significant role in causing foreign policy change in Putin’s first two terms, in his third tenure domestic restructuring has become a much more relevant change agent. Nonetheless, external shocks were still relevant in as much as they sparked the domestic restructuring that caused Putin to shift his policy course.

CHAPTER 4. Russian Foreign Policy Changes in Putin’s 3rd Term

Since he became president again in 2012, Putin has chosen a foreign policy course that has widely been defined as starkly different from the one he pursued during his first two terms as president and from the foreign policies of previous administrations. There has been much talk about how Putin has begun to follow a nationalist, neo-revisionist and neo-eurasianist foreign policy. However, while such a policy undoubtedly represents an international reorientation with respect to the pro-Western, Atlanticist foreign policy course followed by Yeltsin – and it also departs from the pragmatism of Primakov – cannot be regarded as an international reorientation with respect to the foreign policy Putin pursued during his first two terms. Undeniably, in his third tenure Putin has grown increasingly dissatisfied with the way the West has been behaving in the international arena. However, one should not think that this is a completely new posture for Russia, a peculiarity unique to Putin’s third term.

In fact, Marcel De Haas (2010, p.21), on Spechler’s line of thought, wrote that Putin, during his second tenure, had already been following an increasingly assertive foreign policy with respect to the West and the in-between countries that leaned towards it. He argued that at the basis of that forceful foreign policy stance was a mindset that saw Russia as a renascent great power. The enormous increase in oil price was a stimulus for Russia to work harder towards achieving that status since it guaranteed revenues that the Kremlin was able to employ into reaching its goal. As Russia grew economically stronger, and the West experienced economic crisis and military failures, the Kremlin regained confidence and started proposing itself like a great power once again. De Haas wrote that Putin had been striving to ensure that the West would never again neglect Russia as an internationally meaningless player. At the time he was writing, in 2010, he thought that Putin had already achieved his goal and that nobody doubted that Moscow was back as a major international player.

Adding onto this, Fyodor Lukyanov (2016, p.34) points out that both the Russian elites and the ordinary people never accepted the idea of Russia as nothing more than a regional power. In the early 1990s, the West interpreted the fact that Russia had not acted to prevent NATO’s eastward expansion and the EU’s consolidation as the acceptance, by Russia, of the post-Cold-War international order. In truth, Russia behaved as it did only because of its weak economic and political position. The West offered Russia to join the Western-built world order as a minor partner, one that would have to accept Western established rules (and benefit from them), but that could not play a role in shaping such rules. This is a position that Russia could never have accepted.

In other words, Russian resentment towards the West had been on a steady rise for decades, and Putin took advantage of it – and of the relative weakening of the West’s supremacy in the international arena – to reaffirm the country’s position as the great power it used to be. That is to say a superpower whose point of view should always be kept into consideration by the West before it sets out to changing anything in the international order (i.e. humanitarian military interventions resulting in regime changes).

However, by the end of his second term, Putin was not yet satisfied with the status Russia had achieved. In his third tenure, things have been complicated by the fact that energy prices, which had played a crucial role in supporting Russia’s great power aspirations, began to drop consistently, resulting in dramatically worsened economic conditions which sparked domestic protests against him. The predominant leader was thus faced with a conundrum: how to keep his aspirations of Russia as a great power alive, while at the same time silencing the voices of critics and opposition domestically?

Two events in particular that took place in Putin’s third term represented the biggest changes with respect to the foreign policy course he had been following in his first two tenures: the annexation of Crimea and the military intervention in the Syrian war. They represented drastic changes because Russia had hitherto, with the exception of its 2008 war against Georgia, carefully avoided military involvement in foreign conflicts. Another well-known example of Russia’s newly aggressive stance are the military standoffs with the US it recently undertook in the Baltic Sea. A Russian SU-27 fighter jet performed an extremely dangerous barrel roll at close distance of a US surveillance plane. On another occasion Russian fighter jets simulated an attack on a US Navy destroyer (Telegraph Reporters and Reuters, 2016). Several Russian submarines and aircraft intrusions into, or at close proximity of the EU borders have been reported in recent months (De Larrinaga, 2016).

The changes in foreign policy under Putin’s third term cannot be placed under Hermann’s category of international reorientations because they are just different methods of achieving the same goal: making Russia a great power. The radical foreign policy changes that had taken place between phase one and two, and phase two and three of Putin’s foreign policy were program changes and not international reorientations. Today, in the same way, the Kremlin is once again applying adjustment and program changes to accelerate the reaching of its decades-long core foreign policy goal of reaffirming Russia as a great power. However, Putin is adapting his strategy to current circumstances, considering that one new challenge has now been added to the game: striving to be a great power abroad while ensuring the continuation of the regime at home, which no longer looks so certain. In the remaining chapters, I argue that the taking of Crimea and the military intervention in Syria served mostly as instruments to achieve the abovementioned goals. Calling in Hermann’s model once again, the argument is that this newly assertive posture by Russia can be considered a program change: the main goal of Russian foreign policy remains unchanged, namely restoring Russia’s great power status. Instead, what have changed are the methods used to achieve the main objective.

4.1. The Annexation of Crimea

Daniel Treisman (2016, p.47), professor of political science at UCLA and director of the Russia Political Insight project, considered three potential explanations of what might have led Putin to take the decision of annexing Crimea. These were: (1) a fear that NATO would have encircled Russia if Ukraine, under its new government, had joined the organization (and that it could have expelled Russia’s Black Sea Fleet from its Sevastopol base when Russia’s lease on the base had been guaranteed by earlier Russo-Ukrainian treaties to last until the 2040s); (2) the possibility that the taking of Crimea might have been the first step of a long-planned strategy by which Putin, in a neo-imperialist fashion, would be attempting to restore Russian borders to those of the Soviet Union; and (3) the annexation of Crimea as an improvised response to the fall of the Yanukovych government, again stemmed by the fear that Russia might lose the Sevastopol base.

Indeed, as mentioned several times in this dissertation, NATO’s expansion towards Russia’s borders has always been considered a serious threat by various Russian administrations. Moreover, it is publicly acknowledged that Putin didn’t get over the loss of prestige that Russia underwent following the collapse of the Soviet Union, which he famously referred to as the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century (PUTIN, 2005). I have also mentioned that Putin makes no secret of his desire to retrieve and consolidate Russia’s great power status. Fyodor Lukyanov (2016, p.34) is one of the most eminent voices to have declared that annexing Crimea was Russia’s response to NATO’s eastward expansion. He thinks that by getting involved in Ukraine, Russia created a context by which it will be impossible for Ukraine to become a member of either NATO or the EU anytime soon. He sees the taking of Crimea as an extreme way by Russia of telling the West that it must stay out of its zone of influence. On top of it, Lukyanov holds that by annexing Crimea Putin was also righting what most Russians thought of as a historical wrong, namely that Crimea should go back to being Russia, rather than Ukraine.

On his part, Treisman (2016, pp.48-52) – while recognizing that there is some truth to both the “response to NATO’s expansion” and the “imperialist Putin” interpretations – believes that both fail to be sufficiently convincing explanations of why Putin decided to annex Crimea. In fact, Treisman highlights that NATO had made it clear that it had no intention of admitting Ukraine, at least not in the short term, because it considered it too unstable to be a member and because the move would have created unnecessary tensions with Russia. Putin might have doubted NATO’s honesty, but he made no mention of his concerns about a potential accession of Ukraine to NATO in any of his conversations with Western leaders.

As to the interpretation that sees Putin as an imperialist, and the annexation of Crimea as his first expansionist move, Treisman reminds us that the Crimean operation presented many elements of improvisation that are not proper of a country with an expansionist project. The Kremlin seemed undecided as to what to do with Crimea: it changed its mind several times in the space of a few weeks, shifting from the idea of Crimea as a community with greater autonomy within Ukraine to Crimea as part of Russia. Dmitri Trenin believes that blueprints for the annexation of Crimea must have existed since 2008 when Ukraine first showed interest in joining NATO (2016, p.25). However, the fact that a blueprint for the annexation of Crimea had allegedly been around for years doesn’t make Russia an imperialist power. The takeover might as well have been planned in advance, but this doesn’t automatically mean that Russia is an expansionist power hiding scores of blueprinted plans to overtake all of its neighbours. Adding weight to the argument that Russia is not an imperialist power are Andrei Tsygankov (2013) and, notably, Richard Sawka (2015, pp. 77-79), professor of Russian and European politics at the University of Kent. He holds that Russia is still a conservative, status quo power, rather than an imperialist power that intends to conquer its neighbours to recapture all of its Soviet-era territories. Sawka believes that Russia has been pushed towards the adoption of some elements of revisionism because of a failure, on the part of the West, to recognize to Russia its rightful place in the international order that followed the end of the Cold War. He thus considers Russia a neo-revisionist power in the sense that it wants to change those aspects of the international order that prevent it from enhancing its status within such order. Russia is dissatisfied with the way power is currently shared in the international arena, as too much of it is concentrated in the hands of the West. It doesn’t want to change the system as a whole, but it wants to protect its sovereignty, advance its views, and strengthen its great power status. Of the same view is also Marie Mendras (2015, p.81), who argues that Putin is everything but a pure imperialist in his foreign policy and that his actions abroad are instead motivated by a necessity to consolidate his regime domestically (as thoroughly illustrated in Chapter 5).

Treisman finally concluded that the biggest motivating factor behind Putin’s decision to annex Crimea was the fear that – following the ousting of pro-Russian Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych – Kiev’s new government would expel Russia’s Black Sea Fleet from the Crimean base of Sevastopol (Treisman, 2016, p.53). According to such interpretation, Putin’s new foreign policy stance would be that of a leader that reacts impulsively to those events in the international arena that might represent a threat to him and his country’s interests. This interpretation is well in line with Hermann’s vision of external shocks as agents of change. Looking at the taking of Crimea wearing Hermann’s lenses, the possibility that the Russian Black Sea Fleet – fundamental to guaranteeing Russia’s ability to project its military power from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean – could have been kicked out of Crimea by the new Kiev administration, can undeniably be regarded as an external shock that had an effect on a predominant leader. Such shock would have forced Putin to take a quick, thus impulsive decision as to how to best protect one of his country’s most vital interests, which was at stake.

The theory according to which the Sevastopol base was such an important strategic asset to Russia, to the point that even the thought of losing it might have been a big enough shock to spark the decision to annex Crimea is backed by the commander of the Russian military operation in the region, Oleg Belaventsev. He confirmed that Russian officials were extremely anxious that Kiev could have kicked out the Black Sea Fleet (Belaventsev apud Treisman, 2016 pp.49-50).

Treisman (2016, pp. 53-54) argues that if one holds true that the fear of losing Sevastopol’s base was the biggest concern for Russia then the crisis and tensions of the last few years could have been avoided had the new Ukrainian government and its Western allies ensured to Russia that they would have respected the agreement to extend Russia’s right to use the military facility for the next three decades.

Therefore, a few important external shocks, namely the concern of losing Sevastopol, and to a lesser extent, the fear that Ukraine might join NATO, did play a role in shaping Russia’s behaviour in Crimea. However, in the next chapter, I argue that the major driver behind the mission was another, one that had to do with Russian domestic politics and that I have therefore identified with a domestic restructuring: Putin’s need to keep ordinary Russians on his side despite the hard economic times.

Yet, the fear of losing Sevastopol’s base undoubtedly played a role in sparking Putin’s decision to annex Crimea. This makes it necessary to reflect on which other strategic assets are considered important enough by Putin’s Russia to potentially result in another such radical move. Treisman (2016, p.54) rightly notes that the Baltic countries have no Russian bases. This makes a Russian intervention of the Crimean sort in those countries extremely unlikely (if not utterly impossible), especially considering that Putin wouldn’t attack NATO members knowing that would entail a very real risk of starting a military conflict with NATO, which could end up in a nuclear confrontation. Aggressive demonstrations of strength where Russian jets simulate an attack on a US warship or perform a barrel roll over a US plane – as well as the incursions of Russian submarines and military planes into European airspace and territorial waters – are one thing; a military invasion of the territory of a NATO member is a whole different ball game. This should make Western leaders reflect. NATO recently announced its planned deployment of four battalions composed of 4,000 troops to Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia (Barnes & Troianovski, 2016). While the real reasons for such deployment seem to be political, official claims describe the move as a containment measure for fear of a Russian aggression. Such an action is nothing but counterproductive. In fact, although Putin (in his right mind) would never invade the Baltics countries, deploying NATO troops there on the very border with Russia means exactly doing what Putin has always protested against; he will see it as an openly provocative act. The only goal such a decision serves is that of making the tensions with Russia even harsher, making it much more difficult for cooperation and agreements to be reached on other issues (Kureev, 2016).

Another Russian strategic asset that might spark drastic actions by Putin could potentially be the port of Tartus in Syria. However, according to both Treisman (2016, p.54) and Morales (2015, p.3), while protecting the port has been one of the reasons to drive Russia into Syria, it was clearly not the major one. On the other hand, a critical strategic asset for Russia is the Turkish straits, as they represent the only naval gate-away for Russian vessels to enter the Mediterranean. Their closure would complicate efforts by the Russian navy to engage in military operations in the Middle East and elsewhere. Treisman points out that the Russian reaction to such a move by Turkey could be “furious and possibly disproportionate”. He underlines the fact that both Putin and Turkish President Erdogan have a necessity to look strong in the international arena to ensure the support of their domestic audiences. This might lead to dangerous escalations of the tensions between them since the two cannot afford to look weak: in both cases, domestic restructurings are motivating a certain stance in foreign policy.

4.2. The Syrian War and the Russian Intervention

This chapter is not a description of the events that took place in the context of the Syrian war so far. Rather, its objective is to identify, in accordance with Hermann’s change agents, the main drivers behind the Russian involvement in the conflict. Here too, my goal is to demonstrate that a sum of factors, both internal and external, play a crucial role in defining Russia’s most dramatic foreign policy decisions. Of course, getting involved in a military conflict after having spent four years trying to avoid it does represent a foreign policy change. However, this analysis is meant to demonstrate that, in this case too it wasn’t an international reorientation, but rather adjustment and program changes that were still intended to achieve long-established foreign policy goals.

The Russian military operation that began on September 30th, 2015 with airstrikes targeting the Islamic State and, to a greater extent, the anti-Assad rebels backed by the West, was, just like the annexation of Crimea had been, an unexpected event in typical Putin style that left many experts and politicians in disbelief. Just as in the case of Crimea, there are many contrasting interpretations of why Putin decided to intervene military in Syria.

It is widely acknowledged that the most immediate objective of the Russian military intervention in Syria has been to prevent the overthrow of President Bashar al-Assad by the rebels. However, there are several reasons why it is so important for Russia to ensure this won’t happen. I have concluded that these reasons are all in accordance with Russia’s paramount persistent foreign policy objectives (Chapter 1), which haven’t changed under Putin. This comes as proof of the fact that we are not witnessing, under this President, a complete reversal of Russia’s orientation in foreign policy, but rather adjustment and program changes, aimed at facilitating and speeding up the accomplishment of previously fixed, long-standing foreign policy goals.

Javier Morales (2015) identified three main objectives that Russia was and still is pursuing in Syria: (1) reaffirming Russia’s international great power status, (2) protecting Russia’s security from jihadist terrorism, and (3) avoiding the consolidation of the principle of “responsibility to protect” as a norm of international law.

4.2.1 Reaffirming Russia’s International Great Power Status

According to the geopolitical intelligence firm Stratfor (2015), Russia is trying to paint itself as a global leader — an international actor that takes responsibility and is able to stare the United States down instead of bowing to it.

As I explained in Chapter 1, one of the main foreign policy objectives of post-Soviet Russia has been winning back its status of great power and being recognized as an equal, and respected as such, by both the European Union and, especially, the US. Relating this to Syria, had the Western-backed rebels managed to overthrow the Assad regime, Russia would have seen it as a diplomatic victory of the West. In fact, Morales (2015) notes that Russia would have looked weak and incapable of protecting its allies. By intervening and shifting the tide in favour of Assad, the Kremlin has forced the West to recognize that no solution to the Syrian quagmire can be reached without keeping Russia’s opinion into account. This is a way for the Kremlin to show that the world is no longer a unipolar order with the US as the only dominant player, but rather a multipolar order where Moscow plays as big a role as does Washington (i.e. one of the persistent objectives of Moscow’s foreign policy mentioned in Chapter 1).

Therefore, Putin has achieved his goal of getting Russia to sit at the negotiating table with the world’s major powers and discuss a way to solve the most significant international conflict of the moment. He was able to do so from a position of strength since Russia’s intervention has shifted the cards on the table in favour of the regime and broke Western hopes that the rebels alone could defeat Assad. Now, as Russia and the US are considered as the only countries capable of stopping the war in Syria, Putin has achieved his goal of portraying Russia as indispensable to solving major crises: his hopes are that this will force the West to cooperate on Russian conditions (The Economist, 2016). Lukyanov (2016, p.35) holds a very similar view, arguing that more than propping up Assad, Putin’s paramount goal in Syria was to force the US to deal with Russia as a power of equal strength and relevance. Lukyanov saw the President’s choice to pull a majority of Russian troops out of Syria in March as a success of this strategy. Moscow was able to shift the conflict’s course in favour of its ally and to prove its military strength, while pulling out early enough to avoid getting stuck in a foreign conflict for a very long time – a mistake recently committed twice by the US, and a memory very much alive in the minds of most Russians who have not forgotten the catastrophic Soviet mission to Afghanistan. Nonetheless, Putin kept enough forces in Syria to ensure its continued influence in the country. Alexey Levinson (2016), social research director at Levada Center, claimed that Putin’s goal in Syria was to strengthen Russia’s position internationally, a goal that even Russia’s opponents recognized as successfully achieved.

In this respect, both external shocks and domestic restructuring played a role. The possibility of the Assad regime being overthrown by Western-backed rebels was an external shock. However, the struggle for Russia to be recognized as a great power is – apart from a historical necessity and a personal desire of the predominant leader – particularly demanded by the Kremlin’s need to keep ordinary Russians on its side despite the economic recession and international isolation. Hence, a domestic restructuring is one of the driving forces behind the Kremlin’s need to prove Russia’s great power status, as it is doing in Syria.

4.2.2. Protecting Russia’s Security from Jihadist Terrorism

The second reason that Morales (2015) identified for the Russian military involvement in Syria is for protecting its national security against the threat posed by Islamic terrorism. This was also the official justification of the mission given by President Putin: a fight against international terrorism. Indeed, there is some truth to it. Russia fears that a fall of the Assad regime would leave Syria in a situation of complete chaos where it would be fairly easy for Daesh and other terrorist groups such as Al-Qaeda and the Al-Nusra Front to achieve control of the territory. If this happened and terrorist groups obtained a safe-haven from where to run their operations undisturbed (as Al-Qaeda did in Afghanistan), it would be much easier for them to organize and launch attacks against Russia. There are more than licit reasons to believe this could happen, considering that Russian cities were several times in the past targets of Islamic terrorism. Therefore, Morales argues that the Kremlin wants to maintain a secular and united Syrian state, independently of whether it is an authoritarian or a democratic one. To make things worse, more than 2,000 Russian jihadists have travelled to Syria to fight with the caliphate and could come back to hit Russia. If these foreign fighters were to return home and commit terrorist attacks, Putin would risk being discredited and his permanence in power would be threatened. This is especially true considering that – as Morales points out, and as mentioned in Chapter 2 – Putin’s deal with the Russian people is founded on a promise of security in exchange for reduced liberties.

Domestic restructuring and external shocks were the main drivers in this case too. The Islamic State gaining territory and looking ever more threatening amounted to an external shock that got the Kremlin (and the predominant leader) to decide that an intervention was necessary to prevent the terrorist group from becoming too big a threat to Russia’s national security. Even more determinant was the fact that, as Morales wrote, Putin cannot afford terroristic attacks to become the norm in Russia because, if that happened, he would lose the support of the population. This is a good example of domestic restructuring as a foreign policy motivator: the predominant leader, worried about losing the support of those whose backing he needs to remain as powerful as he is today, is driven to take a foreign policy action.

4.2.3. Avoiding the Consolidation of the Principle of “Responsibility to Protect” as a Norm of International Law

Morales (2015, pp.3-5) points out yet another reason why Russia wanted to prevent the fall of the Assad regime, and that is to avoid the consolidation of the principle of “responsibility to protect” as a norm of international law. As mentioned in Chapter 1, Russia has always been a conservative status quo protector. It has always held international law into high consideration, condemning unilateral military actions undertaken by single countries or coalitions of nations without the approval of the UN Security Council (i.e. Iraq in 2003). The 2011 Western intervention in Libya that led to the fall and death of Muammar Gaddafi angered the Kremlin particularly. Russia had agreed to abstain from voting at the Security Council, to allow nothing more than the establishment of a no-fly zone over Libya. Russia is staunchly opposed to the idea of legally establishing humanitarian interventions to protect the population of a country that is being massacred by their own rulers. Rather, Russia insists on the importance of respecting the sovereignty of any nation-state, independent from whether they are democratic or not, and to refrain from interfering in their internal affairs.

Although the Syrian intervention is widely considered as illegal in the West, Putin has tried to justify its legality. He claimed that Russia has been the sole actor to intervene in Syria in accordance with international law since it was the only country acting at the invitation of Syria’s legitimate government. From a Russian perspective, the United States-led coalition targeting the Islamic State is an aggressor because it operates without the authorization of the Syrian government (Stratfor, 2015).

In this case, it is not so straightforward to identify which was the most determinant agent of change. However, the Kremlin is wary of humanitarian interventions as they often end up overthrowing the authoritarian governments of the countries where the interventions are carried out. From Moscow’s perspective, the ultimate goal of the West is to topple the Russian regime too. Therefore, it has an interest in highlighting the illegality of such actions. Since the survival of the Russia regime is involved, once again we can talk about a “domestic restructuring as foreign policy driver” scenario. However, the Kremlin’s fear that the West might have intervened in Syria and forcefully removed Assad was an external shock.

4.2.4. Demonstrating Russia’s Military Prowess to Finalize Weapons Sales

Adding on to Morales’ three main explanations of the Russian involvement in the Syrian conflict, a fourth reason can be identified in the need by Russia to demonstrate its military prowess and attract potential costumers willing to buy Russian weaponry.

Ivan Safronov (2016), from Russia Direct, highlights the fact that although the Syrian campaign had cost Russia $464 million as of the end of March, the government expects to earn, over the next couple of years, $6-7 billion from the sale of weapon systems that were displayed and tested in the Syrian conflict. Indeed, since the beginning of the Syrian campaign, several countries interested in purchasing various sorts of Russian defence industry equipment, particularly aircraft, have contacted the Federal Service for Military-Technical Cooperation. Algeria recently ordered 12 Su-32 Russian bombers. The negotiations over this deal had been protracted unsuccessfully for close to a decade, but the bombers’ stainless performance in Syria got things moving again. This order, added to potential future purchases of military hardware by Algeria could earn Russia $2 billion. Other countries, like Indonesia, Egypt, Pakistan, and Vietnam, have either already signed contracts for, or are negotiating the purchase of Russian aircraft whose combat characteristics were demonstrated in the Syrian conflict. The S-400 air defence missile system has attracted the interest of India and Saudi-Arabia. Iran, Iraq, several former Soviet republics and some of the Persian Gulf states are all potential customers for the T-90 Russian tank after it resisted an attack by a US-made TOW anti-tank missile system in Syria. The episode, which was caught on camera, also had a great symbolic value for Russia, since it showed a Russian-made tank resisting the attack of an American anti-tank missile system.

To connect this to a domestic restructuring might appear a big stretch. However, if one considers that worsened domestic economic conditions were one of the main sparks that lit the anti-Putin protests in 2012, and considering that military industries are one of the few dynamic industries in the country, it does make sense for the Kremlin to be pushing for the sale of armaments as a way to earn revenues that can help it strengthen its control over turbulent domestic audiences.

Other, less significant reasons for Russia to intervene in Syria have been identified, such as the need to prevent the loss of strategic assets and allies in the region. The naval base in Tartus and the air base in Latakia are useful strategic assets (although not vital ones). Furthermore, to Russia, maintaining Assad in power or guaranteeing his succession by a government in which the Alawite portion of Syria will still be represented means keeping an ally in a region where its position has weakened considerably (Stratfor, 2015). I haven’t included a detailed analysis of these motivating factors, as they are minor ones with respect to the four described above.

CHAPTER 5. The Effect of Domestic Restructuring on the Predominant Leader: the Real Key to Understanding Putin’s Foreign Policy