I wrote a few months ago on this blog that I did not think it was possible for Donald Trump to win the 2016 US presidential election. All measures of common sense and learned political science skills lean that way. We can break this down in simple terms:

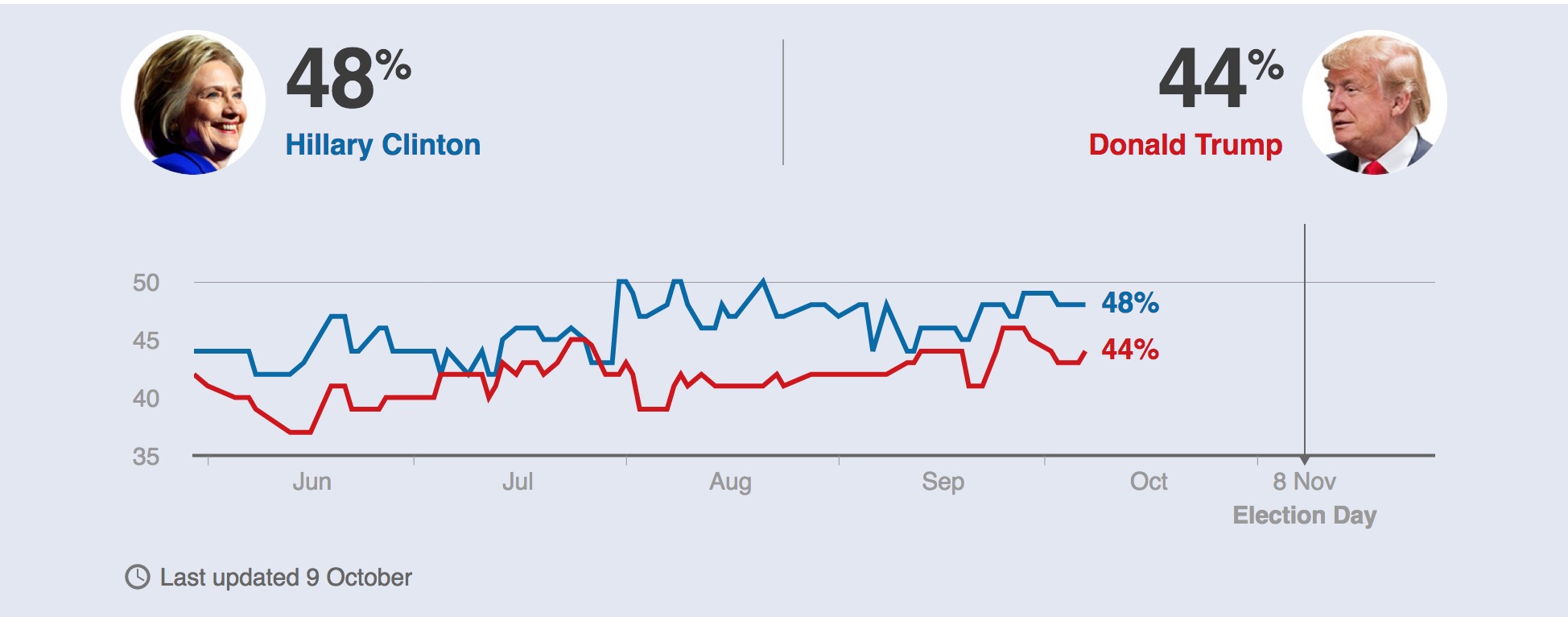

1. The polls are looking solid in favour of Clinton over the long term.

2. Trump seems to have no end of scandals – with the latest one being another reminder of his misogyny and lack of character to hold such a high office.

3. Clinton is unpopular, but not unpopular enough to lose against Trump despite his recent apologies.

All these things would make for comfortable reading during normal times. Clinton would sail to victory and the Trump nightmare will fade from memory as a moment of madness on the part of the American public. However, this is the post-Brexit world. Things are stranger than they once were.

What has changed since my earlier post was that Brexit occurred soon after I wrote it. Brexit itself is, of course, nothing to do with US politics or Donald Trump – even though he did give us a bit of light relief when he visited Scotland and babbled on about the Scots ‘going wild’ over Brexit. Countless respectable and learned figures warned of the dangers of Brexit, including the British government. Yet, the more the warnings were emphasised, the more the Brexit ‘leave’ sentiment increased. At the same time the polls failed to detect this. If you swap the idea of Brexit with Trump for president you can see the strategy that he is using to ride out his deficiencies and crises. His campaign has defied all sense of electioneering normality by gauging that enough voters will ignore the tide of critics mobilising against him – even a growing number of senior Republican Party figures. People will go with their gut that America needs Trump, despite all the warnings and facts against it.

Brexit was the starkest reminder yet that people today sometimes do not vote out of logic – but out of gut feeling. This is still poorly understood, though it is making data from polls increasingly unreliable. The phenomenon of voters being dishonest (to a degree) to pollsters is nothing new. The Bradley effect has been studied in the US for decades. Similar discrepancies have been found between polls before elections and results in the UK. But, Brexit demonstrated something on a scale – and with a consequence – that dwarfed prior examples.

If we build further by adding evidence of various public’s mobilising behind extreme figures such as Marine le Pen in France and Rodrigo Duterte in Philippines and add recent events like the people of Columbia voting by majority to reject a peace deal that would end a 50 year conflict, it seems like people today prefer to advocate for more extreme solutions in ever higher numbers.

In sum then, does the scattering of data hinted at here suggest that Trump might defy political gravity? If Donald Trump is elected as President of the USA in November, when added to Brexit, my own understanding of politics will be badly shaken and reality will be weirder than fiction, even as Twin Peaks returns in 2017!

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Trump’s Effective China Strategy

- An ‘Expert’ Perspective on Brexit… Means Brexit

- Brexit Populism: To the Brink of Democracy and an Unholy Alliance with the US

- The Days of May (Again): What Happens to Brexit Now?

- Opinion – Brexit and Its Many Identities in the UK

- Brexit and the 2019 European Elections