Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs) are part of a multibillion-dollar industry supplying both security and logistical services for governments, commercial groups and Non Government Organisations (NGOs). The roles these companies perform include, but are not limited to, security consultancy and armed contracting, recovery of hostages, and logistic support services such as construction and infrastructure support including waste disposal and goods transportation.

Their political significance lies in the fact that they remain an integral feature in how states assemble and practice security governance globally. The scale of their operations and the economic impact they have are also noteworthy. The breadth of these companies’ operations and their use of global workforces are demonstrated best by Group 4 Security (G4S), the largest PMSC. G4S is second only to Walmart as the world’s largest civilian global employer. Boasting over 610,000 employees and operating in over 100 countries, the company reflects the global nature of the security industry. Consequently, PMSC influence world politics not only through changing how states practice security but also by shaping how global workforces are organized.

Overwhelmingly, the PMSC literature continues to focus on state-centric security concerns involving issues pertaining to these companies’ accountability, transparency and legitimacy in global security operations. Often the industry is treated as either a necessary evil that is re-formable through regulations or an example of the ways in which the neoliberal market successfully meets our needs.

Alternatively feminist curiosities take a different departure and subsequently ask different questions. For feminists, there is nothing natural or inevitable about the security industry. Instead, feminists concern themselves with the underpinning gender and racial rationales and logics that render this global business possible in the first place. They ask: what are the gender logics that are called upon in order to sustain divisions of labour within the security industry, how is militarism and masculinities normalized in constructing security companies as viable and legitimate global security providers, whose voices and experiences are made visible and whose are rendered silent and what does this tell us about power?

As such, feminist curiosities about the global industry re-orientate where we located private security, who we see as legitimate security actors and how we produce knowledge about what constitutes security. From the existing feminist research on private security we can take away 4 important points:

- Gender structures the global security industry: Feminists have illustrated that the security industry is not separate from, but a continuation of gender politics within military settings. Maya Eichler’s 2015 edited volume Gender and Private Security in Global Politics, is the first collection of feminist contributions to the critical study of gender and private security. Throughout the book, she and her contributors show us how gender is constitutive of the institutions, practices and logics that underpin the privatization of security. Contributors such as Chris Hendershot, Paul Higate and myself have highlighted how the practice of private security rests upon heteronormative and miltiarised masculine embodiments of those who provide security. Other contributors such as Valerie Sperling and Ana Vrdoljak have demonstrated the neoliberal market assemblages between state and security market that allow for a circumventing of democratic control over security practices—such assemblages have made it increasingly difficult for feminist activists to hold states accountable for human rights violations which disproportionately affect women.

- Militarism and masculinities underpin global security practices: Feminists have shown us that in order to understand how PMSCs feature in contemporary warfare, we need to look at the politics of militarism that shapes them as legitimate security providers. For example, Saskia Stachowitch has shown us the ways in which private security allows for a remasculinisation of security. At a time when state militaries are opening up their ranks to women, LGBT and other minorities, security companies are not compelled by the same political channels to do the same. Elsewhere Stachowitsch has demonstrated the ways in which masculinities as a broader logic feature in sustaining the market as a remasculinised space and the state as feminized. Maya Eichler has documented the ways in which global militarism intersects with ideas of citizenship and capital accumulation. By showing these links she is able to demonstrate how security companies can draw upon global South security labour in the support of broader US and other Western states’ military operations without affording broader political and citizenship rights to these workers.

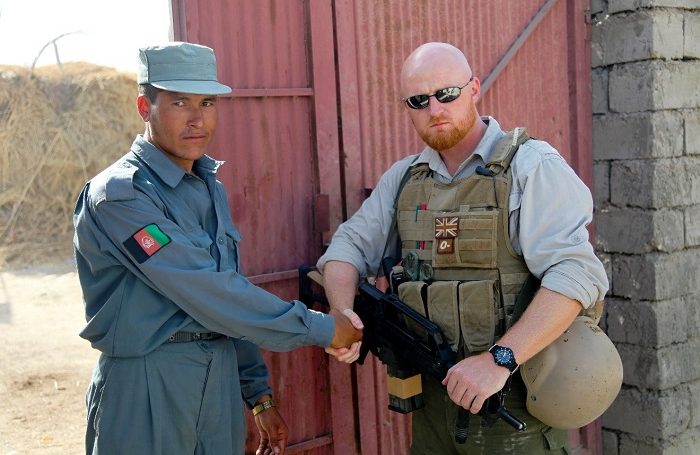

- Western men are made visible whereas women and men of the Global South are rendered invisible: Private security rests upon discursive and material divisions of labour that shape who we see as legitimate actors in global security. Feminists have shown us the politics of military masculinities that fetishize particular men and the men and women who are rendered silent and yet remain indispensible to the global security industry. By looking to the margins of the security industry, feminists have located global South men, labeled Third Country Nationals as an integral part of the global security workforce, the women as reproducers of everyday family life, affective labourers of their husband’s security work, militarized community members that allow for ease in mass recruitment of particular global South workers. By re-orientating to the margins, feminists such as myself, Isabelle V. Barker, Maya Mynster Christensen, and Vron Ware have shown us the gender and racial logics that sustain unequal relations amongst contractors performing security work, and how such logics are a part of broader gendered and racial politics within global capitalism.

- Knowledge production about the industry is always gendered and political: There is nothing neutral about what we read pertaining to private security. Knowledge production about the industry remains gendered and raced. The researcher is central to the reinforcing and resisting of where we locate security and how we understand its value and legitimacy. I have written elsewhere how the researcher matters in the types of knowledge claims we make and how we as scholars interested in private security need to continue to audit our own practices, the ways we empathise or otherwise relate to the industry, and in thinking of Carol Cohn’s important provocation, how we internalise security logics. Paying attention to these practices tells us a great deal of the pervasiveness of everyday logics the industry continues to rest upon in its own production of legitimacy.

In various ways feminists continue to draw our attention to how gender features as rationale that underpins the political and economics of security and sets the conditions of possibilities for the men and women who participate in the industry. I am furthering this research with my new ESRC funded project ‘From Military to Market‘ that examines the racial and gender logics that underpin the unarmed and logistics side of the security industry.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Feminist Foreign Policy Sharpens Focus on Ending Gender-Based Violence as Key to National Security

- The Diplomat: Gender and Security in Popular Culture

- Afghan Women in Geopolitical Imaginaries: Between NATO and India

- Thinking Global Podcast – Kathleen McInnis

- How Often Does the UN Security Council Use a Gender Lens? Not Often Enough

- Gender Troubled? Three Simple Steps to Avoid Silencing Gender in IR