The Other Saudis: Shiism, Dissent and Sectarianism

By Toby Matthiesen

Cambridge University Press, 2015

Toby Matthiesen’s The Other Saudis: Shiism, Dissent and Sectarianism traces the history, historical self-understanding, and status of Saudi Arabia’s religious Other – the native Shia population, focusing on the Eastern Province, and portions of that population living in diaspora throughout Europe, the United States and other parts of the Middle East. Based on extensive fieldwork conducted in 2008 and ongoing conversations with leaders, activists, and local historians, this work presents for the first time a comprehensive analysis of how Saudi Shia see themselves as a community and with respect to the state. Matthiesen particularly strives to allow Saudi Shia to define themselves, rather than seeing them simply as the objects of state policies or as described (and denounced) by the Saudi religious establishment, including within the public education system.

The timeframe of the research is particularly significant because it occurred during a moment of relative openness inside the Kingdom when there was impetus toward fuller inclusion of a variety of categories within Saudi Arabia, including Shia and women. However, much of this groundwork was unsettled with the Arab Spring of 2011, which placed Saudi Shia back under the lens of suspicion as the “threat within” and returned them to the status of objects of state policy and projected identities, rather than tentative participants in its formulation or agents of their own identity.

Matthiesen’s most important contribution is tracing the history and development of several branches of Shiism in the Eastern Province, including the Akhbariyya, Shaykhiyya, and Shiraziyya, giving particular attention to questions about ongoing relationships with and direction from Iran, Iraq and Syria. He notes that Saudi Shia religious education has been severely inhibited by government control over both religious education and facilities, specifically husseiniyyahs and hawzas, and prohibitions on repairs and new constructions. This has reached the point that, unlike in the past, Saudi Shia are no longer capable of producing their own indigenous religious leaders, but must necessarily send them abroad for study and formation. Thus, ironically, the Saudi state itself has created the circumstances that have resulted in increased foreign influence within the Kingdom by denying Shia facilities and opportunities that would allow for the rise of a truly Saudi marji, or high-ranking scholar worthy of emulation.

Matthiesen also works hard to restore Saudi Shia to the main narrative of Saudi history – a location from which they are notably absent in official versions or in which their role is severely downplayed in favor of the Al Saud family. This restoration is part of a broader project among Saudi dissidents in general to restore alternative narratives to the main historical narrative, giving greater attention to both regional dynamics and the roles of tribes other than the Al Saud and their allies. The broader vision of Qatifi history, and of the Eastern Province in general, helps to de-center the Riyadh-Najdi history that has dominated the country since King Abdulaziz’s conquests. Similarly, the in-depth discussion of Shia Courts provides an interesting political commentary on justice and how it was both enacted and received by Shia. The use of tools of justice as a means of political power and control by the state raises questions about the ultimate ability of courts to provide justice, particularly when Shia Courts can be overridden by Sunni Courts for any or no reason, as an expression of state power.

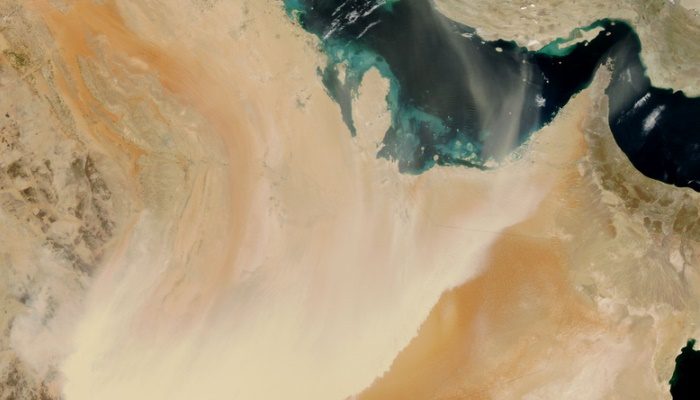

An interesting side story in Matthiesen’s work is the role of the oil sector as the main economic and ideological oppositional driver, located as it is in the midst of the Shia heartland of the Eastern Province. Oil and its revenues have become contentious issues because of the opportunities for employment it provides at the same time that the wealth derived from it is generally not invested in Shia areas. Despite its status as a government corporation, ARAMCO constitutes a social experiment in which Shia have some opportunity for advancement, but nevertheless remain subject to discrimination. Oil workers in the 1950s and 1960s presented the greatest potential challenge to Saudi rule as Arab nationalism and leftist movements infiltrated the workers and led to the formulation of labor unions and strikes. Matthiesen’s sources include newspapers and magazines from the time, tracing the history of negotiations with the government and demonstrating a relative freedom of the press that has not existed since then.

Overall, Matthiesen provides an impressive analysis of primary documents that have never been studied before, some of which remain in private hands. His reconstruction of Shia history and self-understanding is nuanced and rich, albeit sympathetic. He raises many questions as to how the trajectory of the country might have been very different had other choices been made with respect to negotiating with the workers instead of punishing them, for example, or if the apparent graciousness with which the Al Saud were initially received in the Eastern Province and desire for partnership had been reciprocated. As in so many other instances, the Iranian Revolution of 1979 seems to have particularly solidified, if not generated, the impression of the “enemy within,” rather than just the “infidel within,” leaving Shia stuck wanting to be full citizens, but barred because of suspicion, much of which was created by the lack of infrastructure to establish a strong network of Shia leadership within the country. One might reasonably conclude the book by asking whether the events of the Arab Spring are simply a continuation of a long-standing and apparently unbreakable cycle.

If there are any criticisms to be had of the book, they are twofold: one is that it focuses so much on the leadership of various movements – a necessary first step in putting together a history essentially from scratch – that little attention is given to the latest dynamics brought about in the Arab Spring. Particularly missing was the rising frustration of Saudi youth with these established leaders and their failure to achieve the substantive changes they wish to see. The second is that women remain on the periphery of the story. Granted, this work was not a study of women and gender in the Saudi Shia movement, but nearly exclusive attention to male leaders and activists continues the pattern of focusing on male history as the only history worth writing about.

Perhaps Matthiesen will treat us to another work dedicated to analysis of these dimensions of the subject he knows so well, particularly as the future will belong to the youth of Saudi Arabia, female and male alike.