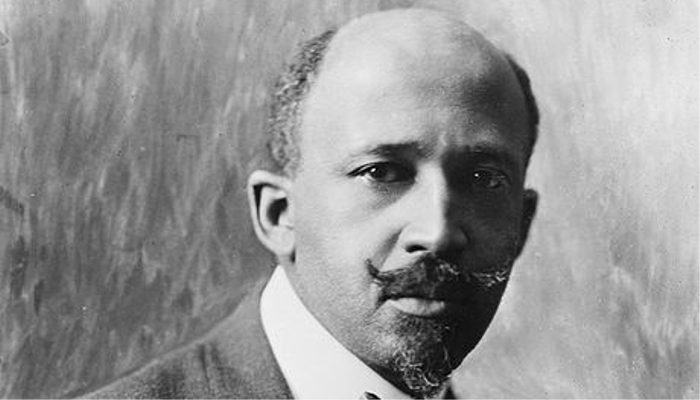

“For the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the colour line.”[1]

By this prophetic statement, W.E.B. Du Bois begins his ground-breaking 1903 treatise, The Souls of Black Folks, in which he discusses the role of race and racism in the United-States and world history. At the dawning of the creation of International Relations (IR), Du Bois presciently highlights the overlooked importance of race and identity in world politics, but also indirectly what would be a century later, still one of the biggest concerns of the discipline of IR: its deeply rooted eurocentrism. Initially marginal, this recurrent critique is gaining increasing support in IR departments, and thus, challenging the very utility and value of the discipline. But to what extent is IR really Eurocentric? The response to this important question demands we clearly differentiate the study of international relations and its practice. Therefore, this piece will specifically focus on the discipline of IR. To do so, this essay will articulate itself around two main pivots: how does the discipline of IR view and understand world politics and how does it view itself. First, this essay will define its key words. Second, it will argue that IR is based on the myth of European exceptionalism. Third, this essay will show that IR has a unique Eurocentric perspective that estranges non-Western realities and assesses them in moralistic terms. Fourth, it will argue that this perception of the world has produced a Eurocentric vocabulary unfit to explain the non-West. Fifth, this piece will argue that the most determinant factor in IR eurocentrism resides in its self-image and the foundational myth of the discipline.

Defining key words

The West accounts for Europe and more recently the United States. Far from representing any moralistic view point, the term eurocentrism will be used for the sake of concision. When talking about eurocentrism or Eurocentric concepts, we respectively mean an ontological position and concepts shaped by the experience of the modern West. Also for the sake of concision, when talking about the world minus the West, we will use the term non-West or non-Western realities.

The foundational myth of the state

IR orthodoxy conventionally dates the emergence of the sovereign state to the notorious 1648 Treaties of Westphalia. This date supposedly marks the end of the suzerain hierarchic order and the beginning of the anarchic state-system in Europe.[2] Yet, this is an over simplification of Europe’s history as “the emergence of sovereignty and the anarchic states-system were the result of a long process of change rather than a clear-cut break with the feudal system of Christendom.”[3] But beyond its historical inaccuracy, the Westphalian myth of the emergence of the sovereign state has three critical consequences for the discipline of IR. First, it assumes the rise of the sovereign state was the product of some kind of European exceptionalism. This poorly challenged doxa ignores the interdependence of Europe, the Middle East and Asia, as well as the imperialist conquest of the Americas prior to 1648, and the deep influence these relations had on the rise of sovereignty in Europe.[4] Second, IR tends to assume that this Westphalian conception of the state has defined the international system ever since 1648, in Europe and abroad.[5] Third, this deep conviction that Western Europe is the birthplace of the sovereign state, implies the existence of a periphery, namely the rest of the world. The discipline of IR has proposed that the modern state was exported from Europe to the rest of the world. On the one hand it did so throughout colonization with the implementation by European powers of Westphalian state-like structures in colonies. On the other, throughout decolonization with the necessity for post-colonial countries to reinforce the Westphalian character of their state in order to compete with these very great powers. It viewed that European states eventually imposed their political system to the whole of mankind.[6] And quite impressively, although the myth of the birth of the sovereign state is criticized, its consequences are not. Probably because it would imply the need to rethink the entire discipline of IR.

IR and its single Western perspective

World history is usually narrated from a Western perspective, indifferent to non-Western realities. For example, World War II is often presented as a consequence of the rise of nationalism in Europe as well as a war between different ideologies, totalitarianism and democracy, between the Axis and the Allies. Yet from a non-Western perspective, this global conflict could also be understood as a confrontation between empires for the control of large areas of influences.[7] The same shift in perspective can be done with the Cold War, not-so-cold for Third World countries, or with today’s war on terror. Moreover, the chronology of events IR is based on, is itself profoundly Eurocentric: for China and Ethiopia, the war began long before 1939, and for Yugoslavia or Vietnam, it lasted long after 1945.[8] The real problem with eurocentrism in IR is not that it considers Europe or the West to be more significant in shaping the international system – a thesis which could be legitimately argued on an empirical basis – but rather that it considers and bases itself on a single narrative of the world and the discipline itself. When looking at events and situations, it will not only look at the experience of the modern West towards it, but also present it as the universally only acceptable way of studying it.

For Barkawi and Laffey, there is not a single authoritative interpretation of World War II, but rather multiple experiences with different geographies and temporalities, depending on the perspective.[9] This has three major consequences. First, the ontological position to see the world from a uniquely Western perspective alienates non-Western scholars, who find themselves engaging with a discipline that estranges and judges their own national reality. For example, African states are often analysed in moralistic terms: if they are stable, we will talk about good governance, if they are not, we will categorize them as failed states. This rhetoric is entrenched in a racialized conception of the world.[10] And instead of changing the theory to fit these realities, we often rationalize these realities into existing frameworks to avoid cognitive dissonance, thus the vocabulary of the failed state. Second, this approach suggests a deeply problematic ranking of suffering. The death of Americans on D-Day will be emphasised while the deadly famine of 1943 in Bengal will be ignored.[11] Third, the more we see the world from a Western perspective, the more Western concepts become unavoidable.

The importance of Western concepts in IR

Chakrabarty explains that:

(…) the phenomenon of ‘political modernity’ – namely, the rule by modern institutions of the state, bureaucracy, and capitalist enterprise – is impossible to think anywhere in the world without invoking certain categories and concepts, the genealogies of which go deep into the intellectual and even theological traditions of Europe.[12]

Indeed, concepts such as the sovereign state and the international system, of course, but also the dichotomy between the public and the private sphere, human rights, law, the individual, social justice or scientific rationality are all the product of European thoughts and history.[13] The problem is not that we are discriminating non-Western scholars and ignoring their work,[14] but rather that even they cannot fully free themselves from the Eurocentric vocabulary of IR. On the one hand, they are forced to reproduce this vocabulary and base their work on classical western IR scholars, to appear credible to their Western counterparts. On the other, these concepts provide a very good foundation to their critique of social injustice in general, and of colonialism or imperialism in particular.[15] Subaltern realist Mohammed Ayoob notes the division between international and national is inapt to explain conflict in the Third World. He argues conflicts find their origins in state building and not interstate disagreement, and that we should concentrate our study on the national sphere.[16] Stephanie Neuman argues IR’s mainstream conception about anarchy and hierarchy is unfit to the study of post-colonial states:

(…) the realist focus on a sharp boundary between domestic order and international anarchy may be applicable, but in reverse. It is the hierarchical structure of the world that provides them with an ordered reality, and a condition of un-settled rules that afflicts them at home.[17]

These attempts to renew our fixed understanding of the cause of war and the dichotomy between the national and the international cannot, however, entirely liberate from the use of Western concepts. The best they can do is challenge the established opposition between anarchy and hierarchy, but still use the two concepts to construct alternative theories.

Another consequence of the use of concepts derived from an experience of the modern West, is that it ignores marginal or unconventional actors that do not fit the Westphalian narrative. The problem is not that IR solely studies Westphalian-like states, which is untrue, but rather that many actors and global phenomena still remain in the blind spot of IR theory. Even liberals, who strive to recognize the importance of non-state actors, seem to do so only with Western actors: multinational corporations, international organizations and NGOs. The current migrant crisis is a good example of this blind spot: undocumented migrants are transnational and highly mobile actors that play a major role in today’s world, yet they are largely invisible to the discipline of IR. The same could be said about the invisibility of sex workers or the depreciation of women’s domestic work.[18] Indeed, in addition to the ineffective study of non-Western realities, IR also fails to incorporate classes and gender into its vocabulary. We could therefore add that the discipline is shaped by a masculine experience of the West.

The foundational myth of the discipline of IR

Just like IR has created a foundational myth about the emergence of the sovereign state around the 1648 Treaties of Westphalia, it has also created an originary myth about its own-self. IR traditionally dates itself to the end of the First World War and the beginning of the 20th century:

1919 was presented as the year when the discipline itself exploded into existence with IR scholars becoming for the very first time enthused with theorising about the international as a subject matter in its own right insofar as it constituted an autonomous domain.[19]

Indeed, the discipline generally understands and presents itself as an attempt, after the calamity of the First World War, to scientifically study war and peace among states so that history would not repeat itself. In other words, IR’s founding raison d’être was to find a solution to the problem of war.[20] If IR cultivates to this day a certain noble image, this essay argues that it was from its very foundation extremely Eurocentric. First, because the need to find a solution to the problem of war came only after a war made a very large number of European casualties and destructed great parts of Europe. Colonial wars, which ravaged the rest of the world during the supposedly long peace of the 19th century, never seemed to arouse such a need. Second, because by nature the study of war and peace necessarily overlooks the relations between the least powerful states of the international system. Therefore, quite ironically, IR is not international in practice. Third, because race and racism were completely side-lined to the margins, when in fact these issues were central to world politics at the time. For example, Du Bois explains that the main determinant of the First World War was the colour line, a combination of imperialism and racism, and not a complicated network of alliances opposing France and Germany.[21] In this sense, IR itself could have even been understood at the time as a “policy science designed to solve the dilemmas posed by empire-building and colonial administration facing the white western powers expanding into and occupying the so-called waste places of the earth.”[22] Fourth, because by instituting the study of international relations as a science, IR rejected any other form of reflection on the subject. The pretence to make a science of international relations excludes many non-Western forms of thinking not based on Western scientific rationality. Fifth, because by giving a well-defined birthdate to IR, the discipline can reject to its ease any prior intellectual tradition and free itself from any kind of longer, deeper and broader history than that of modern Europe. Paradoxically, Chakrabarty notes:

(…) we treat fundamental thinkers who are long dead and gone not only belonging to their own times but also as though they were our own contemporaries (…) these are invariably thinkers one encounters within the tradition that has come to call itself European or western.[23]

The very fact that we do not need to historicize authors such as Kant or Hobbes in a European intellectual context, shows IR still views the West as the natural source of intellectual reference.

Conclusion

In conclusion, IR eurocentrism lies in a mythical conception of world politics and of the discipline itself. On the one hand, the myth of a Westphalian state created in Europe and then only exported to the rest of the world, exists to confirm European exceptionalism and a deeply racialized conception of political modernity. This produces a single Western perception of the world and Eurocentric concepts unfit to explain non-Western realities. On the other hand, the myth of IR as a discipline born from the ashes of the First World War, provides IR scholars with a heart-warming narrative and the noble quest to put an end to the universal problem of war. This identity was probably much needed to establish IR as a credible field of study and to compete against other social science disciplines. As Chakrabarty puts it, “Europe is both indispensable and inadequate.”[24]

Moreover, throughout this essay we have witnessed the incredibly problematic relationship between IR and temporality. IR has a very strong tendency towards presentism and views history as a useful quarry from which scholars can pick historical data points to their leisure in order to support present theories.[25] Instituting the Treaties of Westphalia as a clear turning point from a hierarchical world to an anarchical world enables scholars to study the post-1648 era as an ahistorical temporality. More than just disciplining our thinking, the notion of the sovereign state (and the international state-system) conveniently justifies the following four centuries of European imperialism and sanitizes international relations of its deeply rooted racism.[26]

When discussing IR eurocentrism, a crucial question necessarily arises: can a discipline with such major flaws be saved? This essay argues it can. The discipline of IR needs to engage itself in an open intra-disciplinary dialogue, in order to recognize its profound eurocentrism and racialized conception of the world, challenge its foundational myths, accept new perspectives and develop new concepts. The biggest challenge for non-Western scholars is to avoid developing an academic narcissism of their own. For example, Qing Jianq, who developed a Confucian-based theory clearly rejecting the use of Western concepts, seems to adopt an equally problematic Sino-centric approach. Far from a convincing alternative to eurocentrism, his work is an exaltation of China’s own exceptionalism and expresses profound nostalgia for an ancient grand Chinese civilization.[27] With this difficulty in mind, IR will need to do three things to rethink its disciplinary boundaries. First, reintegrate history and consider Europe as a reality among many others. Second, integrate race (but also gender and classes) to its vocabulary. Third, it needs to historicize social sciences themselves: understand that what we call scientific rationality is also a European historical product and that other process of thought exist. Only then will IR get rid of its ahistorical Eurocentric narrative and its long-lasting academic colour line.

Bibliography

Agathangelou, A. Sexing Globalization in International Relations : Migrant Sex and Domestic Workers in Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey. in Power, Postcolonialism, and International Relations: Reading Race, Gender, and Class. Edited by Chowdhry Geeta and Sheila Nair. London: Routledge, 2002.

Anievas, Alexander, Nivi Manchanda, and Robbie Shilliam. Race and Racism in International Relations: Confronting the Global Colour Line. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015. p. 1-17.

Barkawi, Tarak, and Mark Laffey. “The Postcolonial Moment in Security Studies.” Review of International Studies 32, no. 02 (2006): 329-52.

Benessaieh, Afef. La Perspective Postcoloniale. Voir Le Monde Différemment. in Théories Des Relations Internationales: Contestations Et Résistances. Edited by Dan O’Meara and Alex McLeod. Montréal: CEPES, 2007. p. 365-378.

Buzan, Barry, and Richard Little. “Why International Relations Has Failed as an Intellectual Project and What to Do About It.” Millennium – Journal of International Studies 30, no. 1 (2001): 19-39.

Carvalho, B. De, H. Leira, and J. M. Hobson. “The Big Bangs of IR: The Myths That Your Teachers Still Tell You about 1648 and 1919.” Millennium – Journal of International Studies 39, no. 3 (2011): 735-58.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princenton and Oxford: Princenton University Press, 2000.

Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt. The Souls of Black Folks. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co, 1903.

Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt. The African Roots of War. Boston, 1915.

Hobson, John M. “Provincializing Westphalia: The Eastern Origins of Sovereignty.” International Politics 46, no. S6 (2009): 671-90. doi:10.1057/ip.2009.22.

Neuman, Stephanie and Mohammed Ayoob. International Relations Theory and the Third World. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998.

Qing, Jiang, and Daniel Bell. A Confucian Constitutional Order: How China’s Ancient Past Can Shape Its Political Future. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Shilliam, Robbie. International Relations and Non-western Thought: Imperialism, Colonialism, and Investigations of Global Modernity. Ilton Park, Abingdon, Oxon,: Routledge, 2011. p. 12-27.

[1] Du Bois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folks. (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co, 1903): 1.

[2] Carvalho, B. De, H. Leira, and J. M. Hobson. ” The Big Bangs of IR: The Myths That Your Teachers Still Tell You about 1648 and 1919.” Millennium – Journal of International Studies 39, no. 3 (2011): 738.

[3] Ibid, 742.

[4] Hobson, J. M. “Provincializing Westphalia: The Eastern Origins of Sovereignty.” International Politics 46, no. S6 (2009). 671-90.

[5] Buzan, B., and R. Little. “Why International Relations Has Failed as an Intellectual Project and What to Do About It.” Millennium – Journal of International Studies 30, no. 1 (2001): 25.

[6] Ibid, 25-26.

[7] Barkawi, T., and M. Laffey. “The Postcolonial Moment in Security Studies.” Review of International Studies 32, no. 02 (2006): 340.

[8] Benessaieh, Afef. La Perspective Postcoloniale. Voir Le Monde Différemment. (Montréal: CEPES, 2007): 5.

[9] Barkawi, T., and M. Laffey. “The Postcolonial Moment in Security Studies.” Review of International Studies 32, no. 02 (2006): 340.

[10] Anievas, A., N. Manchanda, and R. Shilliam. Race and Racism in International Relations: Confronting the Global Colour Line. (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015): 11.

[11] Benessaieh, Afef. La Perspective Postcoloniale. Voir Le Monde Différemment. (Montréal: CEPES, 2007): 5.

[12] Chakrabarty, D. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. (Princenton and Oxford: Princenton University Press, 2000): 18.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Shilliam, R. International Relations and Non-western Thought: Imperialism, Colonialism, and Investigations of Global Modernity. (Park, Abingdon, Oxon,: Routledge, 2011): 12-27.

[15] Chakrabarty, D. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. (Princenton and Oxford: Princenton University Press, 2000): 18-19.

[16] Neuman, S., Ayoob, M. International Relations Theory and the Third World. (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998): 31-54.

[17] Neuman, S., Ayoob, M International Relations Theory and the Third World. (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998): 3.

[18] Agathangelou, A. Sexing Globalization in International Relations : Migrant Sex and Domestic Workers in Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey. (London: Routledge, 2002): 142-144.

[19] Carvalho, B. De, H. Leira, and J. M. Hobson. ” The Big Bangs of IR: The Myths That Your Teachers Still Tell You about 1648 and 1919.” Millennium – Journal of International Studies 39, no. 3 (2011): 735.

[20] Ibid, 745-46.

[21] Du Bois, W. E. B. The African Roots of War. (Boston, 1915).

[22] Anievas, A., N. Manchanda, and R. Shilliam. Race and Racism in International Relations: Confronting the Global Colour Line. (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015): 2.

[23] Chakrabarty, D. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. (Princenton and Oxford: Princenton University Press, 2000): 19.

[24] Ibid, 26.

[25] Carvalho, B. De, H. Leira, and J. M. Hobson. “The Big Bangs of IR: The Myths That Your Teachers Still Tell You about 1648 and 1919.” Millennium – Journal of International Studies 39, no. 3 (2011): 755-56.

[26] Ibid, 756.

[27] Qing, Jiang, and Daniel Bell. A Confucian Constitutional Order: How China’s Ancient Past Can Shape Its Political Future. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

Written by: Loïc Bisson

Written at: London School of Economics and Political Science

Written for: Chris Rossdale

Date written: November 2016

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Beyond Methodological Eurocentrism? Knowledge Making and the Universality Problem

- Multiple Worlds of Trauma: Methodology, Eurocentrism, and the Colonial Traumatic

- Walking a Fine Line: The Pros and Cons of Humanitarian Intervention

- Decolonisation and Violence: What It Takes to Decolonise IR

- From Rivalry to Friendship: The European State Systems and the Cultures of Anarchy

- To Reform the World or to Close the System? International Law and World-making