I think, therefore I am. ~ René Descartes, 1637

I meme, therefore I am. ~ Unknown, 2017

Speaking of predictions, or rather visions of the future, I like reading those of the past. There is something essentially human in the act of trying to break from the banality of one’s own existence and explore the Fourth Dimension – Time. Russian futurist and poet Velimir Khlebnikov in his 1921 piece titled ‘Radio of the Future’ (Radio Budushchego) wrote:

Radio of the Future – the main tree of consciousness – will open up the way of solving infinite tasks and will unite mankind. […] Imagine the main camp of the Radio: web of wires in the air, lightning going out and sparkling again, shifting from one end of the building to another. Blue round lightning ball hanging in the air like a shy bird; obliquely stretched wires. Every day flocks of news about the life of the spirit, resembling a spring flight of birds, are spread from this point on the globe.

What used to be a futurist fantasy or intuitive anticipation turns into reality less than a century later (of course, one can argue about whether the news are ‘about the life of the spirit’). The Internet did not kill television, just like previously TV did not destroy radio nor did radio wipe out newspapers, but the Internet co-opted or incorporated previous sources into itself. Whether Khlebnikov’s Radio of the Future resembles the Internet or not, there is little doubt that we are living in a totally different type of society than our ancestors. This society can be called a post-postmodern one, where the first ‘post’ means ‘after’ and the second one means ‘to post [something on the Internet]’. In a recent Russian ad, there is a slogan: ‘If you did not post it, it did not happen’. I think it sums up the zeitgeist of our global village. A mere decade ago, one could talk about how the Internet influenced popular culture, but today ‘the Internet’ and ‘popular culture’ are increasingly becoming synonyms. Even those platforms associated with the latter, and which were not born on the Internet (e.g., movies, and comics), still are spread via the Web, discussed by online audiences, endlessly recycled in cyberspace and, of course, turned into memes.

It is safe to say, the way millennials – either Russian or American – perceive reality is largely influenced by the Internet and its culture(s). As we all have witnessed nowadays, websites that encourage and reward social swarming (i.e. social media platforms) influence politics, from the colour revolutions of the Middle East to Donald Trump’s victory in the U.S. presidential race. A large portion of the content (re)posted and (re)shared on various social media sites is comprised of visual content: videos, pictures, photographs and GIF images, many of which can be attributed to the so-called memes.

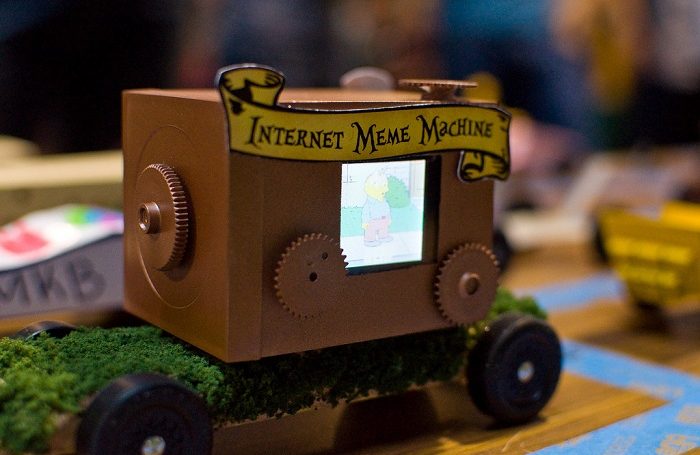

Memes are much more than just funny (or not) pictures and gifs flooding the Internet every day. The term ‘meme’ was first coined by Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene (1976) to designate a unit of cultural transmission that can replicate, mutate and spread. Fast-forward to our time, and we can simply state that contemporary meme is an Idea, reminiscent of Plato’s eidos (εἶδος), a ‘visible form’ of the Internet Age. It is an information virus, spreading like a wildfire fuelled by social media and occupying the minds of hosts, where it spends an incubation period, so that an updated version is set free to roam the Web later.

Battles of ideas in the current year (a meme itself) take place in the form of meme wars. The U.S. 2016 presidential election cycle surely had a meme war component. Both presidential candidates seemed perfectly ‘memefiable’, given their comic book-style personalities: the bombastic billionaire Donald Trump, who turned his name into a brand, and a lifelong politician Hillary Clinton, former Secretary of State and First Lady. Observing the presidential elections from afar, with all the accusations, scandals and dirty tricks, it was like watching real-life Game of Thrones on steroids.

In the (pre-)current year, a politician has to be meme-wise. So, when Hillary Clinton denounced Pepe the Frog, a meme popular among various factions of Donald Trump supporters, it was clear that neither she nor anyone in her staff, who has necessary influence on her, understands how memetics works. As a result, she completely lost the meme war and, as it became apparent on 9 November 2016, the presidency as well. She made a punching bag and a laughing stock out of herself, as was represented in the ‘old lady yells at frog’ meme.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump was riding a giant meme wave on social media, strengthened by his supporters and enhanced by various media outlets. What is interesting about the Trump-Hillary meme war, is that anti-Trump memes either failed or turned out to be pro-Trump via re-appropriation, while even some pro-Hillary memes looked as if they were actually anti-Hillary. (There is another layer to it as the pro-Trump meme team started spreading fake pro-Hillary memes on Twitter, some of which were then unknowingly taken up by Hillary supporters).

Let’s take a closer look at the meme, which at least partially, if not fully, got Trump elected, or as pro-Trump meme warriors would say ‘memed him into the White House’. The initial image of the iconic anthropomorphic cartoon frog was created by Matt Furie in 2005. It had different variations including the happy smiling Pepe saying “Feels good man”, smug Pepe, etc. To make a long story short, five years later images of Pepe started making rounds on the Politically Incorrect channel (/pol/) on 4chan imageboard. In 2015 as Donald Trump was gaining momentum, his image and that of Pepe the Frog merged into one, giving birth to the well-known Trump/Pepe meme. On 13 October 2015, Donald Trump himself retweeted the tweet with a Trump/Pepe image and caption: ‘You Can’t Stump the Trump’.

As if it was not odd enough, the meme magic started to happen then. To grasp it, you should know Carl Jung’s concept of synchronicity, according to which there are acausal meaningful coincidences. Besides serving as a pro-Trump meme farm, 4chan also popularized the use of kek instead of ‘lol’ (laugh out loud). The term originated in the online multiplayer game World of Warcraft. Pepe memes, causing lots of keks, were circulating on 4chan until someone found out that ‘Kek’ is an ancient Egyptian god. Kek (Keku, Kekui) is an androgynous deity of primordial darkness and obscurity, depicted as a frog-headed man. Its female form is called Keket (Kekuit). Moreover, hieroglyph for Kek (probably, a fake one) resembles a person sitting in front of the computer. Hence, the Cult of Kek came to life. The synchronicity does not stop here, as there is a 1986 Italian disco song titled ‘Shadilay’ by the band P.E.P.E. (short for Point Emerging Probably Entering) with an illustration of a green frog holding a magic wand.

In 1993, The New Yorker cartoonist Peter Steiner made a caricature with the following caption: ‘On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog’. In 2017 the more appropriate caption should be: ‘On the Internet, everybody knows you’re a frog’.

Thus, Pepe the Frog meme played a ‘YUGE’ role in crushing the presidential ambitions of Hillary Clinton and memeing Trump into office. Does it sound persuasive enough? It is up to you to believe whether meme magic and the Cult of Kek are real and powerful or not. The fact is that 2016 was the year when memes started coming true: Trump’s presidency was predicted in The Simpsons twice: first time in 2000 and the second in 2015. As the new current year sets in, I am looking forward to new meme wars and strange occasions of synchronicity. Feels good man!

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- JD Vance: The Man, The Meme, The Bipartisan Paradox

- Opinion – How Trump Undermines Europe’s Climate Ambitions

- Opinion – Re-election in Doubt: The Perfect Storm Approaches Donald Trump

- Opinion – In a Knife-edge Election, Two Different Portrayals of America

- Opinion – Nationalism and Trump’s Response to Covid-19

- Good Cop, Bad Cop