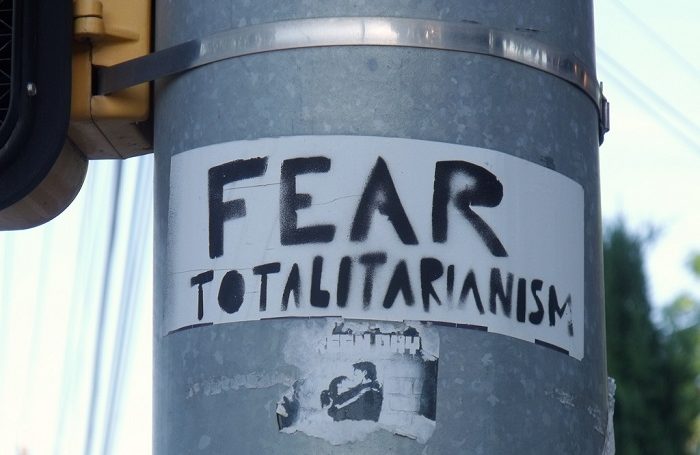

This entry is written both under the shock of US President Trump’s executive order banning Muslims and in hours before teaching that should be used for preparation. But the question that is haunting me is whether we, as teachers, can and should proceed “business as usual” or whether politics is taking over the classroom, or part of it, in certain instances and certain times? I remember very well that no one was teaching as usual during the afternoon of the Tuesday of 9/11 or the next day in the department in which I was then a post-doc. And I perceive the first week of Trump’s presidency and the chaos that he and his administration have created as similar shadows that darken my concentration on “business as usual”. Now, with right-wing totalitarianism back in the West, I feel politically alert and do rethink the political responsibility of academics, especially those in a Politics department. And I well remember when working in the Hans J. Morgenthau archive (in the Library of Congress) that I found some notes in which he complained that the German middle-class in the late 1920s used to talk about Goethe and Heine in front of cosy fire places while National Socialism was hoisting. This complaint is, in different words, about the disinterest in politics by members of the society. According to a fascinating book by the historian Fritz Ringer about The Decline of the German Mandarins this disinterest contributed to Hitler’s rise.

To be sure, the new US administration does assemble a number of people, foremost chief ideologue Stephen Bannon and including its leader, whose aim is a cultural crusade against traditions of Western democratic political thinking and democratic moral values. Ok, Bannon is not Goebbels and Trump is not Hitler, but we certainly must not ignore that they prioritize partisan thinking and acting on behalf of nationalist, racist, autocratic, and narcissistic orientations over democratic rule of law, division of power, free speech, human and civil rights, or constitutional and international law. To be more precise, their crusade seems to be exactly against all of the latter. Hopes that the mandate of the US presidency and its (former?) honourableness will tame Trump have already become disillusioned. Hannah Arendt’s analysis of The Origins of Totalitarianism (first published 1951) perfectly well fits Trump and his administration, apart from the moment of physical violence perhaps; but we also know that violence also manifests as structural and cultural aspects. In this regard an analysis of Trump’s speeches leaves no doubt about their own cultural violence (as well as about its effect of stirring up physical violence, we know many incidents in this direction during his election campaigns).

According to all other criteria, however, mainly in terms of a political ideology, Arendt’s analysis of totalitarianism matches Trump’s politics. Hence we should be alert and not retreat in the hopes and naivety that it won’t be as bad as it looks – because it already is that bad, read totalitarian, and he and the people around him are dead serious in crusading against democratic politics and habitus, which in their view have or are weakening America.

An analysis of speeches, blogs, and editorials of Bannon and his inglorious past as editor of Breitbart News shows two things at least (apart from right-wing, totalitarian content): first, this person is serious in waging a cultural war; and second, he is strategically too smart to be ignored. And now he has become chief adviser to the US president and member of the National Security Council. What else do we need that our alarm bells turn on deep red, not to forget about the actual content of Trump’s executive orders.

But being alerted and to unite against this new form of totalitarianism (and European governments have to be very careful to not become complicit – Theresa May’s visit on Friday, 27 of January, was not very promising here) is not primarily a question of left or right, of republican or democratic (party) orientation (in the US context), but concerns a much more fundamental question, namely that of human respect and decency. That totalitarians are lacking both is probably not that much of a surprise, but that is, apart from the institutional fighting back, what has to be faced, countered, and restored – one of Arendt’s most profound points analysing totalitarian governments and the loss of humanity and “inter-esse”.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Nationalism and Trump’s Response to Covid-19

- Good Cop, Bad Cop

- Opinion – Bad Omens for America after Liz Cheney’s Defeat

- America First Revisited: Trump’s Agenda and Its Global Implications

- Opinion – In a Knife-edge Election, Two Different Portrayals of America

- Opinion – Re-election in Doubt: The Perfect Storm Approaches Donald Trump