This is an excerpt from Migration and the Ukraine Crisis: A Two-Country Perspective – an E-IR Edited Collection. Available now on Amazon (UK, USA, Ca, Ger, Fra), in all good book stores, and via a free PDF download.

Find out more about E-IR’s range of open access books here.

The present chapter aims to analyse several aspects of economic migration from Ukraine to Poland in the context of the military conflict on Ukraine’s territory. It looks at how the Euromaidan and the ensuing war with Russia impacted the dynamics of migration to Poland, which has been for a long time one of the most popular destinations for Ukrainians. It seeks to debunk the myth of the influx of Ukrainian refugees to Poland, promulgated by the Polish authorities, as a way to excuse their unwillingness to share the burden of the international migration crisis faced by the European Union. The chapter looks at the dynamics and significance of economic remittances from Poland. Finally, it discusses the unprecedented socio-political mobilisation of Ukrainian migrants in response to the Revolution of Dignity and the armed conflict on its territory that has resulted in increased consolidation of the Ukrainian migrant population and contributed to the development of migrants’ social capital. The article employs the official data received upon request by the author from several state institutions including the Office for Foreigners, Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, National Bank of Poland and Ministry for Labour and Social Policy; a series of in-depth interviews with Ukrainian civic activists in Poland collected by the Institute of Public Affairs (Warsaw) and Institut für Europäische Politik (Berlin) as well as additional interviews with stake-holders conducted by the author as part of ongoing research on Ukrainian migration to Poland.

The Polish government has been supportive of the pro-democratic forces during the Revolution of Dignity and has backed Ukraine in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict from the start. Public opinion has also been relatively open towards the acceptance of Ukrainian refugees – around half of the population agreed that Poland should admit Ukrainian refugees arriving from the conflict zone (CBOS 2016). Poland organised the resettlement of about 200 Ukrainian citizens of Polish ancestry from the military conflict area, bringing them to Poland and granting permanent residence.

The increased migration flows from Ukraine triggered by the war in Donbas have become embedded into the wider debate on the EU’s response to the unprecedented influx of migrants from Africa and Asia, in particular from Syria, and exploited by some public figures for their political ends. The Polish Prime Minister, in a speech in the European Parliament, claimed that Poland did not have the capacity to accept any Syrian refugees, as it has already accepted one million Ukrainian refugees (Chapman 2016). However, while the migration flow has indeed increased, neither the purported volume, nor the declared character of migration has been reflected by the official data. The vast majority of Ukrainians coming to Poland seek gainful employment and are not a burden on the Polish taxpayer, but rather contribute to the country’s economic growth.

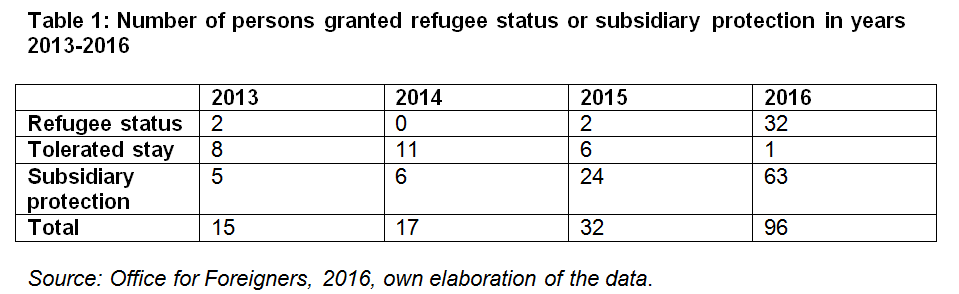

The number of applications for asylum from Ukrainians has indeed increased after 2013 in relative terms, yet even the total number of applications does not come close to the purported one million. If in 2013 there were 46 applications, in 2014 the number rose to 2318 and in 2015 it reached 2305. In 2016, until July, 709 asylum claims were registered. The Office for Foreigners (UDSC) distinguished several main groups: the Crimea, the Euromaidan, and the Eastern Ukraine profile. In terms of the number of submitted applications, currently Ukraine is second only to Russia, as the vast majority of applications come from Chechens. What is more significant, however, the vast majority of applications have been unsuccessful: the number of persons who were granted refugee status or subsidiary protection is just several dozen (Table 1) (UDSC 2016).

Altogether between the year 2013 and 2016 almost 6000 Ukrainians applied for asylum and only 36 persons were granted refugee status, and 161 persons received international protection. As of 4 April 2016, 1600 citizens of Ukraine were receiving social aid (UDSC 2016). While claims about the gigantic number of refugees from Ukraine are vastly overstated, there has been a pronounced increase in the migration flow from Ukraine in the aftermath of the Euromaidan and the ensuing military conflict.

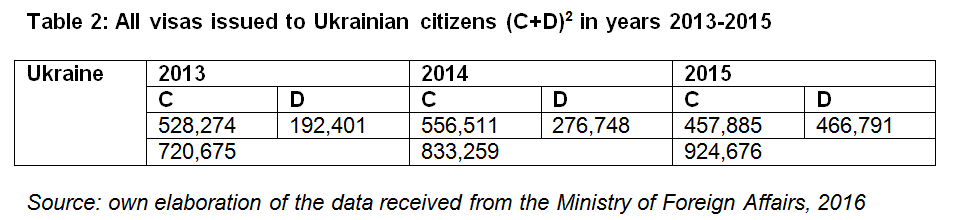

One could wonder where the quoted number of one million comes from. Most likely it refers to the number of Polish visas issued to Ukrainian citizens in the past year. Visa statistics shed some light on the dynamics of short-term, seasonal and circular migration, yet the cumulative numbers are not fully illustrative of migration trends for several reasons. First of all, the almost one million visas encompasses all visas issued to Ukrainians coming to Poland for various purposes, including business, tourism, family visits, conferences, often for just a few days[1].

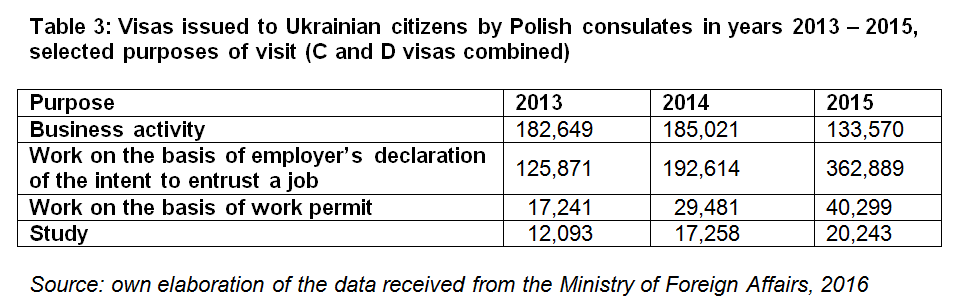

The number of all visas issued by Polish consulates has increased. In 2015, around 200,000 more visas were issued in comparison to 2013.[3] Notably, there has also been a considerable increase in the number of work-related visas (Table 4). If in 2013 the number of visas issued on the basis of employer’s declaration of intent to entrust a job was 125,871, in 2015 it has almost tripled (362,889). The share of study-related visas has also increased almost two-fold.

One needs to be cautious, however, when interpreting these numbers. While they undoubtedly reflect an increased flow of Ukrainians to Poland following the military conflict in the east of Ukraine, the number of visas issued does not necessarily directly correspond to the number of persons coming to Poland or undertaking work in the country. While some visa holders never actually cross the border during the period of validity of their visa, often wishing to have a Schengen visa ‘just in case’, others use the services of fake employers in order to secure a visa and later seek employment after their arrival in Poland, possibly in other EU countries.[4] Notably, the share of irregular migration, contrary to conventional wisdom, is relatively low and according to a large-scale IOM survey study amounts up to 13 per cent of all Ukrainian migrants in Poland (IOM 2016).

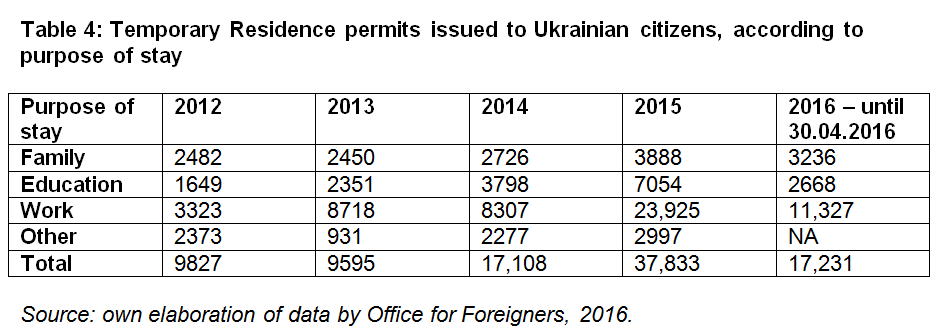

The volume of long-term migration has also increased. As the data collected in Table 2 demonstrates, the number of residence permits (usually valid for one to two years) has almost quadrupled (from 9595 issued in 2013 to 37833 issued in 2015). The majority of temporary permits in 2015 (63 per cent) were issued on the basis of work. This increase also reflects the effects of the Law on Foreigners from 12 December 2013 (art. 114 and 126) introducing a single work and residence permit for stays longer than three months.

As of 1 July 2016, Ukrainian citizens were holding 83,000 residence permits (31 per cent of all foreigners in Poland). This number also corresponds to the IOM estimations of long-term Ukrainian migrants in Poland at the level of 90,000 (IOM 2016). Out of this number 22,500 were permanent residence permits, 57,500 were temporary residence permits and almost 3000 were long-term EU resident permits. In addition, the state issued 143 permits for EU citizen family members, 229 humanitarian protection permits, ten permits based on tolerated status and 17 based on refugee status (UDSC 2016).

Apart from the changes in sheer volume, there has been a significant change in the ratio of men to women, which is often interpreted as evidence that men migrate to escape army conscription. If in 2013 women clearly dominated over men among holders of temporary residence permits (5760 to 4036), in 2015 the situation was opposite: 22,817 men and 15,165 women were granted temporary residence and in the first half of 2016 – 15,672 men and 10,603 women. Moreover, the number of permits on the basis of family reunion, in particular marriage to a Polish citizen and membership of the family of Ukrainian citizen holding a residence permit, has increased considerably compared to the pre-2013 period. Around one in three of these documents are issued to first-time holders while the rest are granted to persons continuing their stay in Poland (UDSC data 2016).

The data on age and gender of visa holders is not available, nonetheless the survey conducted by the National Bank of Poland (NBP) confirms previously mentioned changes in gender mix and also demonstrates that the recent migrants tend to be younger. According to the survey results – which should not be treated literally, but rather as illustrative of the trends – among the new migrants 58 per cent are men, compared to 33 per cent among experienced migrants. In addition, the mean age of the new migrants is 33, as compared to 43 in the experienced migrants group. Moreover, the share of persons originally coming from eastern parts of Ukraine has also considerably increased (28 per cent in the studied group of post-conflict migrants, as compared to six per cent) (NBP 2016).[5]

Ukrainian workers most often work in domestic services, building, construction and remodelling and agriculture (NBP 2016). But there is also an increasing number of highly-skilled Ukrainian workers in IT and communication, science and education, and health care, often graduates of Polish universities.

The number of Ukrainians studying in Poland has also notably increased. According to the IOM survey, Poland is for Ukrainians a top destination for education purposes – 31 per cent of students studying abroad study in the country (as compared to ten per cent studying in Russia and eight per cent in Spain). Student fees and costs of living in Poland are not prohibitive, besides, holders of the Pole’s Card study for free. The number of students enrolled in full-time programmes in 2014/2015 (20,693) has doubled in comparison to 2012/2013 (9620) (Stadnyi 2015). This increase is also reflected in the number of visas and residence permits issued on the basis of undertaking studies in Poland (an increase from 12,093 visas in 2013 to 20,243 visas in 2015 and from 2351 residence permits in 2013 to 7054 residence permits in 2015) (Tables 3 and 4). Students are an important group in the context of economic migration, as considerable part of them will seek employment in Poland or other EU countries after graduation. The law on foreigners from 2013 (art. 187(2)) allows graduates of Polish universities to stay in the country for one year to look for employment.

Significantly, according to the NBP estimates, the presence of Ukrainians on the Polish labour market so far has not impacted either the level of unemployment or salaries (NBP 2016). In other words, they have neither been a burden on the tax payer, nor have negatively impacted the situation of Polish employees.

Remittances

The increase in migration flows from Ukraine to Poland translates into increase of remittances by long-term migrants as well as the size of salaries earned by Ukrainian short-term migrants (and supposedly their remittances as well). While in 2013, according to the National Bank of Poland non-resident Ukrainians earned 3.6 billion PLN (1.2 billion USD), in 2014 it was 5.4 billion (1.5 billion USD) and in 2015 – 8.4 billion PLN (2.1 billion USD[6]) (NBP 2016). While the total amount in Polish zloty more than doubled in 2015 in comparison to 2013, the differences in American dollars are slightly less considerable due changes in exchange rates. There is no clear data on what share of this sum is transferred to Ukraine, as part of it is spent on their sustenance in Poland. If we assume that one third of the salary is spent in Poland on living expenses, around 5.5 billion PLN (1.4 billion USD) was transferred to Ukraine as remittances, savings, and in-kind contributions.

Long-term migrants are less likely to regularly transfer considerable amounts back home – only a share of them have transnational families relying on their support. The remittances by long-term Ukrainian workers via banks and international financial institutions amounted to 55.1 million USD (also an increase, as compared to previous years: 39.9 million in 2012, 40.5 million in 2013, and 39.2 million in 2014) (NBU data 2016). However, this number does not include in-kind contributions, savings and remittances through informal channels made by long-term migrants. However, the official and estimated remittances of Ukrainians in Poland are considerably smaller than the numbers quoted publically by the Polish Foreign Minister, who claimed that Ukrainians sent to Ukraine about five billion EUR to Ukraine last year.[7]

While remittances on macro-level may not play such a significant role as compared to some other countries, they contribute about 50 per cent of long-term migrants’ and 60 per cent of short-term migrants’ household income. The funds are mainly used for basic daily needs (food, clothing), improving the living conditions (furniture and household appliances), and expanding or building a house. Education or investing in business are also mentioned (IOM 2016). Some remittance researchers emphasise that remittances contribute to economic inequality (Kupets 2012, Malynovska 2014), yet the funds received from abroad are spent on domestic products and services, contributing to the overall development.[8]

The Rise of Ukrainian Civil Society in Poland

One of the significant consequences of the Euromaidan for the Ukrainian population in Poland has been an unprecedented civic mobilisation. It has contributed to the integration of the migrant population, the settled Ukrainian minority as well as the wider Polish society. The Ukrainian civil society existed in Poland well before; the Ukrainian minority has had a well-developed organisational structure focused on promoting Ukrainian language and culture for many decades. There also were a number of NGOs supporting Ukrainian migrants, run by both Ukrainians and Poles in Poland, with the largest share of them in Warsaw (for a comprehensive review of formal and informal Ukrainian civil society initiatives see Łada and Böttger 2016). However – as the in-depth interviews with Ukrainian civic activists demonstrate[9] – the dramatic events in Ukraine have motivated many Ukrainians with no prior civil society participation experience to engage in formal and informal civic initiatives, as well as prompted closer cooperation between various existing organisations.

During the Euromaidan in Kyiv and after the annexation of Crimea, Ukrainian NGOs as well as unaffiliated activists organised protests in front of the Russian embassy as well as rallies and public events in support of the pro-democratic civic opposition in Ukraine. These events gathered rank-and-file Ukrainian workers, students, settled Ukrainian academics, civil society activists, representatives of the Ukrainian minority in Poland, as well as many Poles, including politicians and other well-known public figures. A Civic Committee for Solidarity with Ukraine united outstanding Polish public figures, including some representatives of the Ukrainian minority in Poland, as well as settled Ukrainians. Its activities have also helped to draw the attention of the Polish elites and the wider public to the events in Ukraine.

Apart from more formal fundraising initiatives (organised by various groups) there has been a considerable number of smaller, but equally important informal initiates. Funds and in-kind donations have been raised in order to aid the families of Ukrainian soldiers and refugees from the east of Ukraine as well as buy food, clothes, vehicles, equipment and medicine for Ukrainian soldiers. It is next to impossible to calculate the precise amount of funds collected and transferred to Ukraine, because these initiatives have been irregular, often unofficial and sometimes very small. Social media have played a very important role in mobilising Ukrainians, integrating different circles as well as making the fundraising initiatives effective. Many of those initiatives have been run almost solely through social media platforms, in particular through Facebook, benefitting from large transnational networks that include not only other Ukrainian migrants in Poland, but also Poles, Ukrainians in other countries as well as volunteers based in Ukraine, in a way creating a virtual civil society (Kittilson and Dalton 2011). Many of these initiatives have been promoted through dedicated Facebook groups, such as ‘Ukraiński wolontariat w Polsce’. The newly developed social capital will contribute to further integration of the Ukrainian population in Poland.

The period of the Euromaidan and shortly afterwards was also the time when representatives of the Ukrainian community – often PhD students and graduates of Polish universities – were invited to comment and explain the ongoing events in the media. It has become an opportunity to not only provide a better understanding of what was happening in Ukraine, but also to reshape the image of Ukrainians in Poland, who are not only domestic help and builders but also well-educated and knowledgeable experts.

The civic engagement of Ukrainians during and after the Euromaidan has helped to draw the attention of the local authorities and to secure three new centres for the Ukrainian community: the Ukrainian World (Ukrainsky Svit), run by the Open Dialogue Foundation and Euromaidan Warsaw Foundation, the Ukrainian House (Ukrainsky Dim), run by Our Choice (Nash Vybir) Foundation and more recently – the Association of Friends of Ukraine Centre. These institutions provide legal and psychological help to Ukrainian migrants, raise funds and organise public events hosting Ukrainian public figures as well as various artistic events and initiatives, including experimental theatre at the Centre.

The unprecedented mobilisation of the Ukrainian migrant community in Poland has also boosted their self-esteem and increased their sense of agency. Many study participants believe that it has contributed to a more positive perception of Ukrainians by the Polish public opinion (Lada and Böttger 2016). Opinion poll results demonstrate, however, that the overall perception of Ukrainians as a people has not considerably changed in the past few years. Nevertheless, there has been a steady improvement from 15 per cent of Poles having a positive attitude towards Ukrainians in the 1990s to 31 per cent in 2013 and 36 per cent in 2015 (CBOS 2015).

Conclusion

The military conflict on the Ukrainian territory has considerably increased migration flows into Poland as well as made previously seasonal migrants take a more long-term stay. The gender and age mix of the Ukrainian migrant population has also changed, with a considerably increased share of young men. However, it is wrong to assume that Ukrainians arriving in Poland as a result of the conflict are refugees living on government handouts. Only a tiny minority has claimed asylum and just a few dozen persons have actually received a refugee status over the period of the past three years. The vast majority of Ukrainians in Poland are economic migrants earning their livelihoods, contributing to the Polish economy as well as supporting their families via financial and in-kind remittances. The military crisis in Ukraine has not produced an influx of asylum seekers, but resulted in an increase of economic migration.

The financial remittances do not play such a significant role for Ukraine on the macro-scale, as compared to other countries where they comprise a very significant share of the country’s GDP (IOM 2016). Yet, they are a very important source of income for individual households. The total volume of remittances is hard to establish. According to official data 55.1 million USD were transferred through banks and international money transfer institutions by Ukrainians who worked in Poland for longer than a year. But the estimated income of non-resident Ukrainians in Poland for the last year has amounted 2.1 billion USD (8.4 billion PLN). If the assumption that the living costs comprise about one third of their salaries is correct, Ukrainian non-resident workers may have transferred to Ukraine up to 5.5 billion PLN (1.4 billion USD) through informal channels and in-kind contributions.

The Euromaidan and the Russian-Ukrainian war have led to an unprecedented mobilisation of the Ukrainian population in Poland and contributed to the greater institutionalisation of the civil society as well as the development of new Ukrainian centres. Ukrainian migrants’ active engagement in various civic initiatives has boosted their self-esteem and helped to develop their bridging and bonding social capital. It also has contributed to some extent to reshaping the perception of Ukrainians in Poland by native Poles. Further research is needed to see how these developments affect the integration of Ukrainian migrant population into Polish society.

Thus, contrary to the statements of key Polish politicians, the increased presence of Ukrainian migrants in Poland has not been a burden on the Polish taxpayer. On the contrary, it contributed to the overall economic growth as well as public finances (through various official fees and taxes). Not only has the presence of a large number of Ukrainians proved politically uncontroversial, but it also provided political backup for Poland’s tough stand against Russian aggression against Ukraine.

Notes

Ukraiński Wolontariat w Polsce: https://www.facebook.com/groups/303247243198607/?fref=ts

[1] Not all visa holders cross the border, as it is explained below.

[2] It should be noted that persons undertaking business activity, studies or work in Poland may be issued both C or D visas. The decision on the type of visa issued depends on the duration of the intended stay. While a holder of a C-type visa is allowed to stay on the territory of the EU for not longer than 90 days over a 180-days period (yet such a visa may be valid for up to five years), D-type visas are granted for stays that are longer than 90 days, with the maximum stay of one year. Those intending to stay longer need to apply for a residence permit.

[3] It is worth pointing out that the dynamics of visas issuance numbers are related to the term of validity of C visas issued: the issuance of multi-entry visas with long-term validity (up to five years). According to the statistics collected by the European Commission around 70 per cent of C visas issued by Polish consulates are multi-entry, yet their validity may vary from six months to five years. If people who travel to Poland on a regular basis are granted visas with relatively short validity, visas granted to them artificially boost statistics.

[4] As it turns out, the declaration of intent to entrust work system, while considerably liberalising the access to the labour market for Ukrainian workers, is prone to various abuses and malpractices. In general, it is perceived that getting a visa on the basis of a work declaration is relatively easy, and thus an option chosen by many Ukrainians. This is especially the case if one uses the services of intermediary Ukrainian companies cooperating with Polish companies whose main source of income is precisely issuing declarations of intent. According to the data collected during the State Labour Inspectorate investigation of companies that had issued work declarations in 2014, only 69 per cent of Ukrainians who were issued declarations actually entered the territory of Poland. Out of those who entered Poland in 2014 on the basis of visa issued on grounds of declaration of intent, only 37 per cent took up jobs with the employer who issued the declaration. For more, see the State Labour Inspection report, 2015.

[5] Importantly, this data is not fully representative of the whole population and thus should not be treated literally. Yet it illustrates some trends characteristic of this group of migrants. The survey study was implemented by the Migration Studies Centre Foundation using the Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS) on a sample of 710 respondents employed in the area of Mazovian voivodship in the Warsaw metropolitan area and localities specialising in agricultural produce.

[6] According to the exchange rates from 30.12.2013, 30.12.2014 and 30.12.2015, respectively.

[7] ‘More than a million of Ukrainians who live in Poland annually transfer – only through official bank channels – about ten billion PLN, and the same amount in cash they transfers when visiting their families in Ukraine. This means that last year, according to the NBP, as a result of their work in Poland, Ukrainian citizens transported about five million EUR. This is an important support for the Ukrainian economy’ (my translation of the quotation from Minister Waszczykowski’s speech at the IX Europe-Ukraine Forum in Łódź): http://wpolityce.pl/polityka/279295-minister-waszczykowski-polska-bedzie-wspierac-suwerenne-decyzje-ukrainy

[8] Other negative side-effects, apart from typical problems of transnational families, include both official (bank accounts and loans) and unofficial (household savings) dollarisation, which in turn limits the effectiveness of monetary policy, makes the banking system more vulnerable to economic crisis and currency depreciation; increasing inequalities; and reducing political will to undertake necessary reforms (Kupets 2012; Grotte 2012; IOM 2016).

[9] I would like to thank the Institute of Public Affairs and the Institut für Europȁische Politik for sharing the transcripts of in-depth interviews with representatives of formal and informal civil society initiatives of Ukrainian migrants, the Ukrainian minority as well as their Polish partners conducted as part of the project „Ukraińcy w Polsce i w Niemczech – zaangażowanie społeczno-polityczne, oczekiwania, możliwości, działania”, supported by the Polish-German Foundation for Science and PZU Foundation.

References

Association of Friends of Ukraine, http://www.tpu.org.pl/pl/towarzystwo/

CBOS, “Stosunek Do Innych Narodów,” Komunikat z Badań, NR 14/2015.

Chapman, A. “Poland Quibbles Over Who’s a Refugee and Who’s a Migrant,” Politico, 22 January 2016, http://www.politico.eu/article/poland-quibbles-over-whos-a-refugee-and-whos-a-migrant-beata-szydlo-asylum-schengen/

Civic Committee for Solidarity with Ukraine, http://www.solidarnosczukraina.pl/index.php/pl/home-page/jak-dziala-komitet

Grotte, M. “Transfer dochodów ukraińskich migrantów,” in Migracje obywateli Ukrainy do Polski w kontekście rozwoju społeczno-gospodarczego: stan obecny, polityka, transfery pieniężne edited by Brunarska, Zuzanna, Grotte, Małgorzata and Magdalena Lesińska, Warsaw: Centre for Migration Research Working Papers, 2012: 58-84.

Kittilson, M. and Dalton, R. “Virtual Civil Society: The New Frontier of Social Capital?” Political Behavior 33 (2011): 625–644.

Kupets, O. “The Development and the Side Effects of Remittances in the CIS Countries: The Case of Ukraine,” CARIM-East Research Report, Migration Policy Centre, February 2012.

Łada, A. and Böttger, K. (eds.) #EngagEUkraine: zaangażowanie społeczne Ukraińców w Polsce i w Niemczech, Warsaw: Institute of Public Affairs, 2016.

Malynovska, O. Перекази мігрантів з–за кордону: обсяги, канали, соціально–економічне значення, Київ: Національний інститут стратегічних досліджень, 2014.

Narodowy Bank Polski (NBP), “Bilans Płatniczy Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej za IV kwartał 2015 r.,” Warszawa: NBP, 2016.

Nash Vybir Foundation, http://pl.naszwybir.pl/

Open Dialogue Foundation, http://odfoundation.eu/

Stadnyi, Y. “Українські студенти в польських внз (2008-2015), [Ukrainian Students in Polish Higher Education Institutions], CEDOS think tank (2015), http://www.cedos.org.ua/en/osvita/ukrainski-studenty-v-polskykh-vnz-2008-2015

State Labour Inspection, “PIP (2015) Sprawozdanie z działalności Państwowej Inspekcji Pracy w 2014 roku,” Warszawa, 2015.

UDSC Office for Foreigners, “Raport na temat obywateli Ukrainy,” Warszawa, 2016.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – The Rise of Islamophobia in Poland

- Opinion – A New Pact on Migration and Asylum in Europe

- Opinion – A State of Emergency at the Polish-Belarusian Border

- The Exploitation of Ukrainians: Additional Consequences of an Armed Conflict

- Opinion – Poland’s Territorial Defense Forces: A Solution for Revitalizing Canada’s Reservists

- Opinion – Challenging the European Migration Agenda