This is an excerpt from Migration and the Ukraine Crisis: A Two-Country Perspective – an E-IR Edited Collection. Available now on Amazon (UK, USA, Ca, Ger, Fra), in all good book stores, and via a free PDF download.

Find out more about E-IR’s range of open access books here.

For many years, Russia was the second greatest world recipient of migrants after the United States and it currently holds the third position, after Germany, with 12 million newcomers a year. It is the main destination country for various categories of migrants from South-Eastern Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia (SEECA), with 38.4 per cent of all immigration directed towards this country (Migration facts and trends… 2015, 34). Citizens from post-Soviet states, specifically from the 1991-founded Commonwealth of Independent States (which includes Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and associated countries – Turkmenistan and Ukraine) have comprised the biggest number of migrants in Russia ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Migration to Russia from these countries has been almost ten times higher than from other countries of the ‘far abroad’. According to official statistics in 2013, 422,738 people arrived from the CIS and 59,503 from countries outside of the region. Such a mass migration from CIS states into Russia has been facilitated by the visa-free regime, but also by close economic, political and personal relations between the people – and later due to disparities in the economic development of CIS countries, which encouraged labour migration to the more developed Russia.

Over a span of 25 years, the character of migration, state policy and official rhetoric towards migrants have changed dramatically – being dependent on the Russian labour market and often forced to work informally, many migrants have suffered from the growing restrictions of migration law and the lack of policy to facilitate better integration.

This chapter will address the formation of the myth of a ‘dangerous migrant’ through politics’ and mass-media constriction of migrants’ image as connected with crime, disease and illegal work. The restrictions of migration legislation bring a lot of complications and contribute to the ambiguous position of migrants in the society. One of the main problems facing migrants in Russian society is racism and xenophobia, which often enjoy the support of the state and mass-media. Due to the armed conflict in Eastern Ukraine which began in April 2014, almost a million people have sought refuge in Russia, which according to the UN, is the ninth largest displaced group in the world. The chapter discusses the existing regulations and the main issues facing the refugees.

This paper is based on several years of the author’s research on migration in Russia, including her Open Society Institute funded project ‘The everyday lives of Central Asian migrants in Moscow and Kazan in the context of Russia’s Migration 2025 Concept: from legislation to practice’, during which she conducted about 300 in-depth interviews (with Dr. John Round) between 2013 and 2015; the 2012-2014 Russian Foundation for Humanities funded project titled ‘Social integration of migrants in a context of social security’ (with Prof. Laissan Mucharyamova), with a survey of 297 migrants, in-depth interviews with migrants and experts and discourse analysis; and the ongoing 2016-2017 British Academy Small Grant funded project titled ‘Asylum seekers from Eastern Ukraine in Russia: identities, policies and discourse in the context of forced migration from the Ukraine conflict’.

The Myth of a ‘Dangerous Migrant’ and Tightening of Migration Control

Portraying migrants as dangerous because of the supposedly high crime and unemployment levels among them and the fact that they contribute to the destruction of national identities, is common across the globe (Vertovec 2011). The rise of xenophobia and nationalism in Europe and the United States supported by political disourse (Wodak, Boukala 2015; Chavez 2013 etc.), has brought tremendous changes in political agenda. In Russia the rise of xenophobia towards migrants goes in parallel with increasing control in migration policy. As Shnirelman (2007) pointed out: ‘if in the middle and second part of the 1990s Chechens were portrayed as the main enemy, in the beginning of the 2000s after announcing the new war as an ‘antiterrorist operation’, the mass-media started the active cultivation of a negative image of migrants.’

The changing official stance of President Putin in relation to the idea of a multi-ethnic society explains a lot. While in 2012 he spoke about a ‘complex and multidimentional’ country and argued that ‘if a multi-ethnic society is struck by the bacilli of nationalism, it loses its strength and stability’ (Putin 2012)[1], in 2014 his rhetoric reflected a very different view. He stated: ‘we still have quite a few problems here that have to do with illegal, uncontrolled migration. We know that this breeds crime, interethnic tensions and extremism. We need a greater control over compliance with regulations covering migrants’ stay in Russia, and we have to take practical measures to promote their social and cultural adaptation and protect their labour and other rights’ (Putin 2014).

Thus, Putin has drawn an unsubstantiated connection between migrants’ irregular status and crime, extremism, and ethnic tensions. The time period between these two statements saw an increase in xenophobic attitudes in Russia, the Moscow mayoral election (in which the candidates focused on demonising the Other), round-ups and public detention of migrants, and attempts to securitise migration policy. Inter-ethnic tensions have been exacerbated through the increase in the number of workplace raids, after which the ‘illegal’ migrants would be paraded through the streets. In addition, sweeps of the metro system in search for criminals (i.e. irregular migrants) have been well covered by the media. The migrants were also blamed for the poor health care system and rising crime levels.

The media has portrayed migrants as bringing disease to Russia, even though HIV infection rates, the most commonly discussed illness, in Central Asia are much lower. The first deputy of the State Duma Committee for Ethnic Affairs, Mikhail Starshinov, stated without citing any data that a ‘huge number of migrants have dangerous diseases such as tuberculosis, HIV and various “shameful diseases”’ (Chernov 2014). HIV in Russia has been viewed as an imported disease with authorities and doctors blaming migrants for the increasing number of infection cases (Pichugina 2012; State Duma 2013; TV Center 2013). Moreover, migrants are often portrayed as drug abusers lacking in health education, sexually promiscuous and unable to control themselves, thereby putting the native population in grave danger. The media has also focused on showing migrants accessing health care for free, attacking particularly Central Asian women who deliver babies in Russian hospitals (see Primor’e 2013). Blaming migrants accessing prenatal and antenatal care for ‘medical tourism’ does not correspond with a reality when woman often have to go to their countries of origin to give birth as an alternative to dealing with often xenophobic attitudes in hospitals (Rocheva 2014).

The migrant-criminal figure is another standard othering tool in all migrant recipient countries. In Russia it was taken to the extreme when the mayor of Moscow, Sergey Sobyanin, stated that the city would be the world’s safest capital if only migrants were not committing crimes (Sobyanin 2013). These constructions show migrants as a dangerous and superfluous flow towards what is, to employ Mbembe’s theory of necropolitics, a ‘let to die’. Our research demonstrates that migrants are simultaneously visible and invisible to the state; the legal uncertainty denies them access to welfare and a voice within society, but they are visible for exploitation both in terms of their labour and the political capital gained from their presence (Round and Kuznetsova 2016).

While they are often portrayed as dangerous, the reality is quite different: migrants often become subjects of hate crime attacks. The Comitee for Civil Assistance supported by the Sova Centre created a map at hatecrime.ru website which has reported on hate crime incidents in Moscow and Moscow Oblast since 2010, and registered 565 attacks. According to Sova Centre’s data, migrants from Central Asia traditionally have constituted the largest group of victims (in 2014 one person was killed and 17 were injured). 11 victims (one killed, ten injured) were of unspecified ‘non-Slavic’ appearance, usually described as ‘Asian’. In addition, there are five victims among migrants from the Caucasus (in 2014 three were killed and 13 injured) (Alperovich and Yudina 2016, 11).

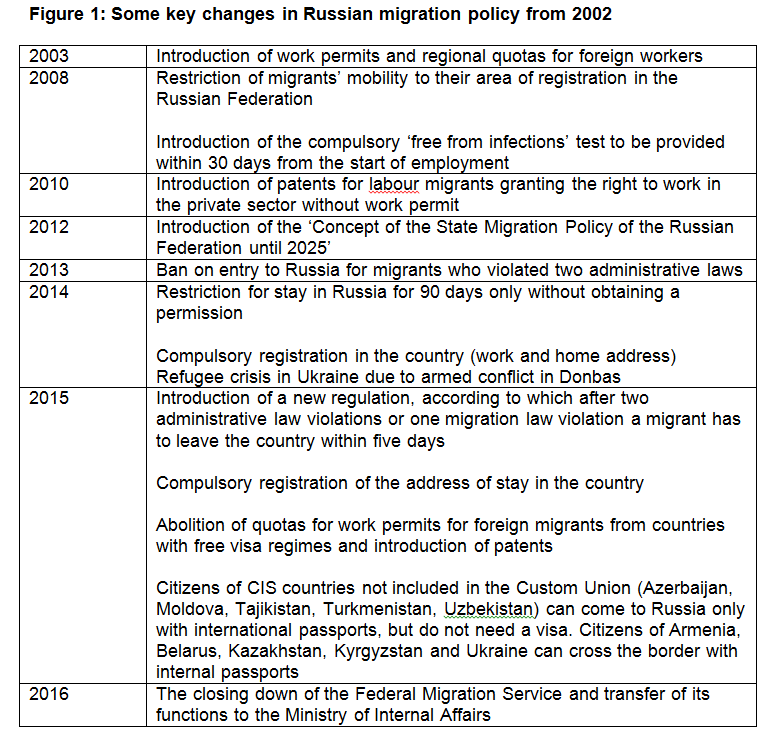

From the beginning of 2000s, migration policy in Russia has been shifting towards increasing control of immigration and restriction of migrants’ labour rights, enabled by new laws. Human rights activists and migrant rights advocates worry that most of the changes in Russian migration law will have a negative effect on the employment and living conditions in Russia and will also affect the citizens of post-Soviet states who can enter the country without a visa (see Figure 1 for a brief outline of some important changes in migration policy).

On 1 July 2010, patents for labour migrants were introduced, which gave migrants the right to work in the private sector without a work permit. According to Ryazantsev (2012), in the beginning this law helped to regularise the status of approximately half a million migrants who earlier preferred to work unofficially. The new measure was so popular that in the first six months from its introduction, the authorities received more than one million applications.

In 2013, Russia introduced an entry ban for those migrants who had committed two administrative law violations. In 2014, the allowed stay in the country without any permission document was limited to 90 days, down from 180. The new law introduced in 2015 requires migrants who have committed two or more administrative or one migration law violation to leave the country within five days. Administrative law violations include offences such as unpaid penalty for driving, violations of migration law – for instance being registered in one apartment, but living in another. Due to these measures from 2012 to 2014, the number of CIS citizens banned from entering Russia increased more than nine times (from 2013 to 2015, 1.6 million people received such a ban) (Troitsky 2015, 20). As a result, about four per cent of the total population of Tajikistan, or more than half of those who worked in Russia in 2015, were banned from the country, according to the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Migration of Tajikistan (cited in Troitsky 2015, 22). Civil rights activists reported mass violations of human rights. In most cases migrants were not allowed to read their court cases, as there were no interpreters available. The scale of abuse was huge; the Moscow court, for instance, considered 42 cases in one hour for migrant deportation (Troitsky 2015), which shows the lack of any in-depth consideration of individual situations.

In 2015 Russia experienced a massive decrease in international migration from post-Soviet countries. The greatest reduction in migration growth was in the case of Tajikistan (47.8 per cent compared with 2014) and Kyrgyzstan (41 per cent). Moreover, Russia experienced a 42.6 per cent decrease in the number of migrants from Uzbekistan (Social’no-jekonomicheskoe polozhenie Rossii 2015, 246).

While Russian citizens pay a penalty if they live in an apartment without registration, foreigners who do the same face deportation. Such a practice can be referred to as the ‘ethnicisation’ of politics (Gulina 2015). In addition, the new Russian migration laws affect the citizens of some CIS countries and significantly restrict their freedom of movement and opportunities to work. We can suppose that it is partly because the articles of the Convention of the CIS regarding human rights and freedoms in the area of employment do not have any control mechanisms (Davletgildiev 2016, 37), but more importantly, because of Russia’s special role in the CIS and the lack of protest from Tajikistan and Moldova in response to these restrictions.

2015 was a crucial year for migration policy because of the new law introducing compulsory tests in the Russian language and Russian history, and additional laws for all foreigners who plan to work in Russia (with the exception of citizens from the EEU countries, highly skilled migrants, and several other categories). These exams not only increased the financial burden for labour migrants, as most of them have a salary which is lower than the regional average, but were immediately followed by administrative barriers. Respondents complained that 30 days to pass the exam was not enough considering the time needed to register and the waiting list. Moreover, certificates from exams passed on the regional level are not recognised in the rest of the country. At the same time, the costs of the federal exam have been much higher and the waiting time – much longer. The Presidential Council on Civil Society and Human Rights has suggested changes in the new law, such as getting rid of the history and law components in the exam, since such a knowledge is of no use to foreign citizens temporarily employed in Russia (Jekspertnoe zakljuchenie… 2015).

One of the most significant changes to migration policy has been the shutdown of the Federal Migration Service and the transfer of its functions to the Ministry of Internal Affairs (Ukaz… 5 April 2016). Even before this reform, analysts argued that ‘courts have become part of the chain of migration policy implementation, focusing on regulating the number of foreign citizens in the Russian territory, especially from some countries’ (Troitsky 2015, 51). The new change will bring an even greater turn of migration policy towards police control.

Refugees from Eastern Ukraine in Russia

The armed conflict in Eastern Ukraine began in April 2014, affecting an area with approximately 5.2 million inhabitants. An estimated 9000 people have died, 14,000 have been wounded, and over a million have been internally displaced within Ukraine as a result of fighting (UN reports 2015). In the first six months of the conflict over 835,000 Ukrainian citizens from the war-torn areas arrived in Russia to seek asylum (Svodnyj doklad 2014) and over half a million Ukrainian citizens received provisional asylum in 2015 and 2016 (Chislennost’ vynuzhdennyh pereselencev… 2016).

Centers where people displaced from Ukraine could stay were set up, usually in former pioneer camps, health hotels etc. Soon after, however, several Russian regions were assigned refugee quotas and Moscow stopped inviting more people to settle in those areas. It is important to mention here that the influx of people from Ukraine saw the rise of volunteer activities and civil society groups to support the refugees and provide them with food, clothes and sometimes a place to live. The Civil Assistance Committee and Migration and Law NGOs provided free advocacy services in several Russian regions to assist refugees.

However, as one of the countries with the highest number of asylum claims in Europe, Russia has been more inclined to grant applicants provisional asylum rather than refugee status; between 2014 and 2016 only 505 Ukrainian citizens received it (Chislennost’ vynuzhdennyh pereselencev… 2016). Data gathered during the author’s research show that a number of Ukrainian citizens from war-affected territories do not have provisional asylum and live in Russia as labour or undocumented migrants. Some of those people moved to Russia before the war and others come from regions not included in the list of conflict-affected territories, which has been the requirement to receive asylum. Overall, in 2015 there were 2.6 million registered Ukrainian citizens living in Russia.

The situation of Ukrainians from war-affected territories is likely to change with the new law, adopted on 1 May 2016, introducing a simplified procedure for issuing residence permits to Ukrainians who have received a refugee status or provisional asylum. In addition, according to the new law, those who will take part in the federal programme of assistance for volunteer migration will be treated as compatriots living abroad. Previously, residence permits were issued often even a year after one moved to Russia (Federal Law ‘On the amendments to the Article 8 of Federal Law “On the legal status of foreign citizens in the Russian Federation” from 1 May 2016 № 129’).[2]

Despite a large volume of applications from Ukrainian citizens, there is an ongoing confusion in relation to the procedure they shall follow and the support they are entitled to. They can remain in Russia for 180 days without a visa and significant resources were initially allocated to providing living facilities for this group. However, from pilot research it has been clear that Ukrainian asylum seekers experience the same problem as other migrants, as they become mired in bureaucracy, corruption, and the general lack of recognition of migrants’ human rights. Despite the allocated resources and administrative support to assist refugees, people have trouble finding official employment due to their status. Another problem is mental health. After dramatic events, in some cases followed by the loss of home and family, people need psychological support and, according to our research, there were not enough opportunities to receive it.

Undocumented or ‘Illegal’?

In both the political and media discourse migrants have been commonly portrayed as ‘illegal.’ Following the words of Elie Wiesel, a Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize winner: ‘No human being is illegal’, human rights activists in many countries campaign to avoid using this term. The International Organization for Migration and the United Nations use the term ‘irregular migration’ and restrict the use of term ‘illegal migration’ to ‘cases of smuggling of migrants and trafficking in persons’ (International Organization of Migration 2011).

However, such nuances do not exist in the Russian state and media discourse, which promotes an extremely narrow definition of informal work, assuming that the workers take up unofficial employment for tax avoidance purposes, and thus by default are illegal. As Williams et al. (2013) have shown, many ethnic Russians struggle to operate fully in the formal labour market due to employers’ practices, but in the case of labour migrants the situation is even more problematic. In Russia, various studies demonstrate that informal workers made up between one-fifth and one-third of the total employment in 2013 (Gimpelson and Kapeliushnikov 2014). It is unavoidable for both the labour market and for migrants as well. Labour migrants, as the interviews revealed, in many cases are offered either cash in hand payments, or extremely low formal salaries. According to our survey in Kazan in 2013, 54.5 per cent of labour migrants had neither a patent, nor a work permit (Kuznetsova and Mucharyamova 2014a, 47).

The issues surrounding employers’ practices are perhaps the most pernicious in the whole process, as they force labour migrants to operate informally, thereby reducing their security and salaries and enabling the state to view them as ‘illegal.’ For example, a large number of migrants from post-Soviet countries worked in preparation for the Sochi Olympics. Human Rights Watch exposed a pattern of abuse across a number of major Olympic sites which included non-payment of wages or excessive delays in payments, employers’ failure to provide written employment contracts or copies of contracts, excessive working hours, illegal withholding of passports and other abuses (Race to the Bottom… 2013). Our research showed also that migrants were often under attack by Cossacks and police raids, arrested and kept in humiliating conditions. Migrant and Law network has supported those who did not receive their wages by initiating court cases against the employers. Nevertheless, many of them have not been resolved, as it was impossible to track the chain of sub-contractors.

Even when labour migrants work formally, they still occasionally face legal obstacles. For instance, in November 2013 many cities in Russia experienced a collapse in public transportation services because of a new legislation which prohibited driving with licenses issued in other countries. Thus, 80 per cent of drivers in Yekaterinburg and 70 per cent of drivers in Petropavlovsk-on-Kamchatka have not been able to work on 5 November 2013 (Shipilov 2013). Neither the migration office, nor the municipal council informed bus companies about the new procedures. In the same year, the chief of the Russian Duma Committee on State Security, Irina Jarovaya, suggested to prohibit migrants’ work in trade, but the initiative was never implemented (Jarovaya 2013).

The social construction of ‘illegality’ does not only block migrants’ possibilities to receive a fair wage, but makes them ‘invisible’ for the state. Our analysis of data gathered by the Medical Information and Analytical Centre of the Republic of Tatarstan found that in 2012 the majority of foreigners did not have medical insurance (2560 migrants out of 2584) (Mucharymova, Kuznetsova and Vafina 2014; Kuznetsova and Mucharymova 2014b). The only accessible care without an insurance policy is emergency care (Postanovlenie Pravitel’stva … 2013), but even this was questioned at the beginning of 2016 by Duma deputy Vladimir Sysoyev who requested that the Ministry of Health Care reconsiders providing migrants with free emergency assistance (Runkevich and Malay 2016). Working in Russia has become a challenge in terms of access to health care, especially for those employed in sectors such as construction and trade, due to the lack of safety regulations in the workplace, extremely long working hours and little time for relaxation. Both documented and undocumented workers have extremely limited access to Russia’s health care system and thus they often turn to paid services they can barely afford, informal care or do not undertake any treatment.

The fear of being ‘illegal’ even among documented migrants negatively impacts on people’s everyday lives, limits the available options for spending free time, affects community building and creates a huge psychological pressure (Round and Kuznetsova 2016).

Conclusion

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia became one the largest migrant receiving countries. Most of the immigrants come from the post-Soviet states of Central Asia whose economies partly depend on remittances, as well as from Ukraine, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Belarus. Although the visa-free regime for citizens of the Commonwealth of Independent States made it relatively easy for people to work in Russia, restrictions in the migration law introduced in the last decade have created barriers for safe life and employment in the country, and contributed to the decrease of labour migration. The Russian state and society have made a lot of effort to support refugees from Eastern Ukraine by arranging special employment conditions for this group, however, the refugees still face issues related to integration. When it comes to labour migrants, the work and living conditions for foreigners from post-Soviet countries have been challenging. Those with non-Slavic appearance are often subject to xenophobia and racist attacks. Moreover, due to the large size of the informal economy, migrants face issues related to access to health care and work safety. They live under stress, having to cope with constant changes in regulation and the risk of exclusion.

Notes

*This work was supported by funding from the British Academy, Open Society Institute and the Russian Foundation for Humanities. The author would like to thank Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska and Dr Greta Uehling for their insightful comments on the paper.

[1] In Russian: ‘если многонациональное общество поражают бациллы национализма, оно теряет силу и прочность’ (Putin 2012)

[2] Assistance to Ukrainian citizens coming to Russia due to armed conflict in Donbas became the priority of the State Programme for Voluntary Emigration of Compatriots Living Abroad to Russia. In 2014 and the first quarter of 2015, 70,900 Ukrainian citizens registered in Russia with the programme, which makes 47.5 per cent of all compatriots who migrated to Russia (Monitoring… 2015, 16).

References

Alperovich, V., Yudina, N. “The Ultra-Right Movement under Pressure: Xenophobia and Radical Nationalism in Russia, and Efforts to Counteract Them in 2015,” in Xenophobia, Freedom of Conscience, and Anti-Extremism in Russia in 2015: A collection of annual reports by the SOVA Center for Information and Analysis edited by Alexander Verkhovsky, Moscow: SOVA Center, 2016: 7-66.

Chavez, L. The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013.

Council Under the President of the Russian Federation for the Development of Civil Society and Human Rights, “Svodnyj doklad o merah po okazaniju podderzhki licam, vynuzhdenno pokinuvshim territoriju Ukrainy i razmeshhennym na territorii Rossijskoj Federacii ot 31 Oktjabrja 2014 [Report about measures for support to people had to leave Ukraine and had asylum in Russian Federation from 31 October 2014],” 2014, http://president-sovet.ru/documents/read/282/

Davletgildiev, R. “Avtoreferat dissertacii na soiskanie stepeni doktora juridicheskih nauk po special’nosti 12.00.10 – Mezhdunarodnoe pravo. Evropejskoe pravo ‘Mezhdunarodno-pravovoe regulirovanie truda na regional’nom urovne.’ [Abstract of the doctoral dissertation in Law in specialty 12.00.10 International Law. European Law ‘International legal regulation of labor in regional level’],” Kazan: Kazan University Publishing House, 2016.

Demoscope, “Vos’moj ezhegodnyj demograficheskij doklad Naselenie Rossii 2000. 5.7. Bezhency i vynuzhdennye pereselency’. [Eighth annual demographical report on population of Russia. 2000.5.7],” http://demoscope.ru/weekly/knigi/ns_r00/razdel5g5_7.html

Federal Service for State Statistics, “Chislennost’ vynuzhdennyh pereselencev, bezhencev i lic, poluchivshih vremennoe ubezhishhe (chelovek, na 1 janvarja) [Number of displaced people, refugees and people received temporal asylum (persons for 1 January)],” 2016, http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/population/demo/tab-migr4.htm

Federal Service for State Statistics, “Social’no-jekonomicheskoe polozhenie Rossii, Federal’naja sluzhba gosudarstvennoj statistiki [Social and Economic state of Russia],” 2015, http://www.gks.ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_main/rosstat/ru/statistics/publications/catalog/doc_1140086922125

Gimpelson, V. and Kapeliushnikov, R. “Between Light and Shadow: Informality in the Russian Labour Market,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 8279, Moscow: Higher School of Economics, 2014.

Gulina, O. “Jetnizacija fenomena migracii v zakonodatel’stve [Ethnization of Phenomena of Migration in Law],” Journal of Tomsk State University. History 5, no.37 (2015): 24-33.

Human Rights Watch, “Olympic Games in Sochi,” 2013, https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/02/06/race-bottom/exploitation-migrant-workers-ahead-russias-2014-winter-olympic-games

International Organization of Migration, “Key Migration Terms,” 2011, http://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms

International Organization of Migration, “Migration Facts and Trends: South–Eastern Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia,” 2015, https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/migration_facts_and_trends_seeeca.pdf

Kuznetsova, I. and Muchyaramova, L. “Labor Migrants and Health Care Access in Russia: Formal and Informal Strategies,” The Journal for Social Policy Studies 12, no.1 (2014): 7-20.

Kuznetsova, I. and Muchyaramova, L. Social’naja integracija migrantov v kontekste obshhestvennoj bezopasnosti (na materialah Respubliki Tatarstan) [Social integration of migrants in a context of social security (case of Republic of Tatarstan)], Kazan: Kazan University Press, 2014.

Malakhov, V. “Russia as a New Immigration Country: Policy Response and Public Debate,” Europe-Asia Studies 66, no. 7 (2014): 1062–1079.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Gosudarstvennaja programma po okazaniju sodejstvija dobrovolnomu pereseleniju V rossijskuju federaciju sootechestvennikov, prozhivajushhih ZA rubezhom,” https://guvm.mvd.ru/about/compatriots

Mucharyamova, L., Kuznetsova, I. and Gusel. V. 2014, «Sick, patient, client: the positions of labor migrants in the russian health care system (evidence from the Republic of Tatarstan),» Vestnik Sovremennoi Klinicheskoi Mediciny [The Bulletin of Contemporary Clinical Medicine] 7, no.1 (2014): 43-50.

Mukomel, V. “Rossijskie diskursy o migracii: ‘nulevye gody’.’ [Russian discussions about migration: ‘zero’ year],” in Rossija reformirujushhajasja: Ezhegodnik-2011 (Vol 10), edited by Mikhail Gorshkov. Moscow, Saint-Petersburg: Institute of Sociology of Russian Academy of Sciences, 2011: 86–108.

Presidential Board of the Russian Federation, “Jekspertnoe zakljuchenie na proekt Federal’nogo zakona ‘O vnesenii izmenenij v otdel’nye zakonodatel’nye akty Rossijskoj Federacii’ (v chasti porjadka poluchenija patentov trudovymi migrantami). 2015. [Expertise on bill of Federal Law ‘About ammendments in some legislation of Russian Federation (rules of patents’ receiving)],” 18 August 2015, http://president-sovet.ru/documents/read/383/

Putin, V. “Vladimir Putin, Rossija: nacional’nyj vopros,” Nezavisimaya Gazeta, 23 January 2012, http://www.ng.ru/politics/2012-01-23/1_national.html

Reeves, M. “Clean Fake: Authenticating Documents and Persons in Migrant Moscow,” American Ethnologist 40, no.3 (2013): 508–524.

RIA Novosti, “Putin: nuzhno kontrolirovat’ sobljudenie pravil prebyvanija migrantov [Putin: We must control following rules of migration regime],” 20 November 2014, http://ria.ru/society/20141120/1034333285.html

Rocheva, A. “A Swarm of Migrants in our Maternity Clinics!’: The Study of Stratified Reproduction Regime in the Case of Kyrgyz Migrants in Moscow,” Journal of Social Policy Studies 12, no.3 (2014): 367-380.

Rossijskaya Gazeta, “Postanovlenie Pravitel’stva Rossijskoj Federacii ot 6 marta 2013 g. N 186 g. Moskva ‘Ob utverzhdenii Pravil okazanija medicinskoj pomoshhi inostrannym grazhdanam na territorii Rossijskoj Federacii,” 11 March 2013, https://rg.ru/2013/03/11/inostr-med-site-dok.html

Round, J. and Kuznetsova, I. “Necropolitics and the Migrant as a Political Subject of Disgust: The Precarious Everyday of Russia’s Labour Migrants,” 2016, Critical Sociology, DOI 0896920516645934.

Runkevich, D. and Malay E. “Skoruju pomoshh’ predlagajut sdelat’ platnoj dlja migrantov,” Izvestya, 14 January 2016, http://izvestia.ru/news/601529

Russian Informational Agency, “Jarovaja predlagaet zapretit’ migrantam rabotat’ v sfere torgovli,” 3 September 2013, https://ria.ru/society/20130903/960371221.html

Ryazantsev, S. “Patenty vyveli ‘iz teni’ bol’she milliona migrantov.’ [Patents revealed from shadow more than a million of migrants],” Migratsia 2, no.11 (2012): 45-47.

Shipilov, E. “Migrantov zapretili po oshibke,” Gazeta, 5 November 2013, https://www.gazeta.ru/auto/2013/11/05_a_5737725.shtml

Shnirelman, V. “Jetnicheskaja prestupnost’ i migrantofobija [Mass-media, ‘ethnic crime’ and migrantophobia],” in Jazyk vrazhdy protiv obshhestva edited by Alexander Verkhovsky, Moscow: Sova centre, 2007.

Sobjanin, S. “Rabota mjera interesnee prem’erstva’ [Sergei Sobyanin: The work of the Mayor is an interesting premiership],” Izvestia, 13 July 2013, http://izvestia.ru/news/551895

Troitsky, K. “Administrativnye vydvorenija iz rossii: sudebnoe razbiratel”stvo ili massovoe izgnanie?” Moscow: Civil Assistance Committee, 2015, http://refugee.ru/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/doklad-o-vydvoreniyakh1.pdf

Ukaz Prezidenta Rossijskoj Federacii ot 5 aprelja 2016 g. № 156 ‘O sovershenstvovanii gosudarstvennogo upravlenija v sfere kontrolja za oborotom narkoticheskih sredstv, psihotropnyh veshhestv i ih prekursorov i v sfere migracii,”http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/51649

Verhovsky, A. “Jazyk moj… Problema jetnicheskoj i religioznoj neterpimosti v rossijskih SMI. [My language… The issue of ethnic and religious intolerance in Russian mass-media],” Moscow: Sova Centre, 2002.

Verkhovsky, A. “The Rise of Nationalism in Putin’s Russia,” Helsinki Monitor 18(2) (2007): 125.

Vertovec, S. “The Cultural Politics of Nation and Migration,” Annual Review of Anthropology 40 (2011): 241–256.

Vesti, “V Primor’e vyjasnjajut, pochemu vrachi ostavili migrantku rozhat’ na poroge’ roddoma [It is explained why doctors left a migrant to deliver a baby outside],” 7 November 2013, http://www.vesti.ru/doc.html?id=1151352

Wodak, R. and Boukala, S. “European Identities and the Revival of Nationalism in the European Union: A Discourse Historical Approach,” Journal of Language and Politics 14.1 (2015): 87-109.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – War in Ukraine: Why We Should Say No to International Civil Society

- Opinion – Refugee Hierarchy in Western Responses to the Ukrainian Crisis

- Opinion – Europe’s Division Deepens with Russia’s Council of Europe Expulsion

- Opinion – The Myth of Being Anti-Racist and Anti-War in the Ukraine Conflict

- Opinion – The European Union’s Status in the Russia-Ukraine Crisis

- Opinion – On and Beyond Whataboutism in the Russia-Ukraine War