Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East

by Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel (eds.),

London: Hurst Publishers, 2017

In this new book, co-editors Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel bring together some of the most prominent political scientists, historians, anthropologists and religious studies scholars who focus on the Middle East to make sense of a largely misunderstood and systemically misused concept: sectarianism.

It may seem that a problem as pressing and crucial as sectarianism has been dealt with thoroughly enough by now. Alas, as this definitive book reveals, the term “sectarianism” continues to be used and misused by world leaders, intellectuals, journalists, and even scholars as a “catch-all explanation” for the problems of the Middle East today (p. 2).

Indeed, sectarianism is a dominant theme in concurrent Middle East contentions. However, this book challenges conventional wisdom that relates today’s sectarianism to ancient blood feuds embedded in primordial hatreds between Sunnis and Shi’a, as if Arab peoples have maintained medieval religiosity and static identities despite their historically changing geopolitical and social contexts.

Instead of this normalized Orientalist view of Arab identity politics, this book presents a historically grounded perspective on the systemic and deliberate use of sectarian identities by both, regional powers and their local allies and clients, to promote and advance their interests and positions. Central to this book’s argument on sectarianism is, therefore, the role of Arab elites, whose concerns over their “staying power and staying in power” in largely fragile states have corroded the polities and societies of the region (p. 9).

To make sense of this perspective, this book first suggests replacing the term ‘sectarianism’, which seems to connote a historically-static phenomenon, with the term ‘sectarianization’, defined as “a process shaped by political actors operating in specific contexts, pursuing goals that involve popular mobilization around particular (religious) identity makers” (p. 4).

The book is divided into two parts. Part I provides a historical and theoretical perspective on sectarianization, which prepares the reader for rich case studies into the mechanisms of sectarianization and its diverse and particular manifestations in Part II.

The Beginning of Sectarianization

The first chapter, authored by Ussama Makdisi, is an enlightening read (or re-read) of history of sectarianization. Makdisi adeptly unravels the beginning of modern sectarianism, which is usually traced back to the dawn of Islam. Alternatively, Makdisi presents a historically-grounded claim that sectarianism, as we know it today, is in fact a product of modernity. Makdisi discusses how, in the nineteenth century, permeable ideas of nationalism, equality and secular citizenship posed a challenge, not only to the Ottoman imperial order, but also to the United States and Europe, which previously built their order and legitimacy on religious and/or racial differences (p. 26).

The Ottoman Empire sought to consolidate power during increasing imperial pressure from Western powers through constitutional change which disestablished Muslim supremacy and, instead, enforced political equality between Muslim and non-Muslim subjects. This comprehensive “ideological and legal reordering of the empire”, known as the Tanzimat, redefined the relationship between Muslim and non-Muslim subjects, as well as their relationship with the state, consequently triggering unprecedented forms of inter-sectarian conflicts (p. 27). Following a series of massacres and sectarian conflicts, the Ottomans and European powers institutionalised sectarian political structures across the empire, sectarian quota systems and sectarian forms of representation, sometimes without the prior consent of the local population. Sectarian institutions and consociational power arrangements were considered by imperial powers to be the only viable arrangement to contain the ‘problem’ of religious pluralism.

The Sectarianization of Geopolitics

Following the formation of nation states in the Middle East, sectarianization took different forms and manifested itself in varying policies and narratives, depending on the context and the state. Three main historical events have had regional and defining impact on the rise of sectarianization: The Iranian Revolution in 1979, the US invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003, and the recent wave of revolts in 2011.

For instance, Bassel Salloukh eloquently emphasizes the 2003 US invasion and occupation of Iraq as a crucial event that created a new regional landscape, dominated by Saudi-Iranian geopolitical confrontation “fought out not through classical realist state-to-state military battles, but rather through proxy domestic and transnational actors and in the domestic politics of a number of weak Arab states” (p. 38).

The sectarianization of post-war Iraq, and, more broadly, the Middle East, is sensibly addressed by Fanar Haddad in Chapter 6. Haddad argues that treating the US invasion in 2003 as the moment of sectarian outburst, whereby one can draw a line between “sectarian” and “non-sectarian” Iraq, overlooks the “cumulative factors that had been developing over several generations” under an authoritarian regime (p. 101). While 2003 was indeed pivotal in exacerbating sectarian contentions to unprecedented levels, Haddad’s chapter relates this moment to a history of mismanagement of sectarian plurality, as well as “subtle forms of sectarian entrenchment and sectarian politics characteristic of the pre-2003 era” (p. 102).

This is also highlighted in Yezid Sayigh’s rigorous chapter, where he argues that sectarianism must not be reduced to colonial or imperial policies, thus ridding the Arab peoples from their agency. Instead, Sayigh calls for a greater focus on what has been happening in recent decades within the borders of Arab states, and less so on who drew the borders in the first place.

The Sectarianization of Arab Popular Uprisings

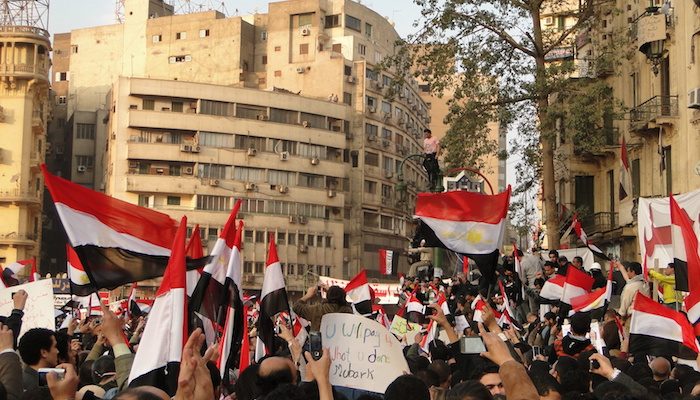

As the Arab peoples stood courageously against their ruthless authoritarian regimes, demanding bread, freedom, and social justice, many thought that Orientalist narratives on the presumed incompatibility between Arab societies and democracy have been empirically debunked once and for all. Alas, the complicated, bloody, and violent outcomes of the Arab Uprisings have led to the reproduction of Orientalist explanations (neo-Orientalism) as to why Arabs have continuously failed to democratize. Neo-Orientalism discredits the democratic possibilities and aspirations of the Arab Uprisings, and plays into the hands of re-emerging (or persistent) authoritarian regimes who, as this book rigorously contends, have used sectarianism, rhetorically and empirically, to maintain their grip on power.

This is best examined in Madawi Al-Rasheed’s pithy chapter on Sectarianization as a counter-revolutionary policy, where she delves into sectarian narratives which regional powers, mainly Saudi Arabia and Iran, propagated as an effective way to delegitimise popular uprisings across the region and, at the same time, co-opt this mobilisation and reduce it to a sectarian binary. For instance, Al-Rasheed argues that Saudi Arabia’s counter-revolutionary strategy consisted of invoking sectarian difference and hatred “to thwart the prospect of peaceful protest to demand real political reform” (p. 152).

Alluding to crude facts on policies and narratives of regional powers at times of democratic, peaceful uprisings, Al-Rasheed exposes the “instrumentalization of religious differences, diversity, and pluralism in political struggles of regimes against their own constituencies” (p. 154). This book underlines how authoritarian regimes in the Middle East have had decades of experience in instrumentalizing religious differences. This experience explains why regimes and their regional backers have been so effective in thwarting the prospect of democratic change, co-opting popular mobilization, and, in some cases, renewing allegiances to authoritarian regimes.

Instead of denying or underestimating the pervasiveness and significance of sectarianism today, which has been a lazy response to neo-Orientalism, this book presents an exceptionally comprehensive, multi-disciplinary, and historically sound explanation not only of sectarianism (or sectarianization), but, also, of why sectarianism continue to be systematically misused by people in power across the world.

Thanks to Hashemi and Postel, we have a book that stands out as a strong reference to the history of sectarianism in the Middle East, as well as the mechanisms of power politics behind it. Their exceptional efforts, as well as that of the esteemed authors, serve our collective duty to historicize the Arab Uprisings in the face of counterrevolutionary attempts to record the events, if at all, as vile moments outside history.

Despite its shared authorship, the book maintains a clear and concise language accessible to all readers, making it a compulsory read for academics, journalists, students, and anyone who is interested in finding rather nuanced answers to the naturally complicated outcomes of the Arab Uprisings.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Interview – Matteo Capasso

- Review – Break All the Borders: Separatism and the Reshaping of the Middle East

- Review – Erdoğan’s Empire: Turkey and the Politics of the Middle East

- Review – The Great Betrayal: How America Abandoned the Kurds and Lost the Middle East

- Review – Rebel Governance in the Middle East

- Now Recruiting – Middle East Editors