This is an excerpt from Migration and the Ukraine Crisis: A Two-Country Perspective – an E-IR Edited Collection. Available now on Amazon (UK, USA, Ca, Ger, Fra), in all good book stores, and via a free PDF download.

Find out more about E-IR’s range of open access books here.

One of the key points of contention leading to the Ukrainian crisis was the debate over whether to sign the Association Agreement, aiming to increase Ukraine’s integration with the European Union. The controversy came as a result of the perception that any agreements with the EU would necessarily be a move away from integration with Russia. In the end, Ukraine proceeded with the signing of the Association Agreement in 2014, and Russia moved forward with its plans to create the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), which came into being on 1 January 2015. The management of labour migration in the framework of the EEU offers a glimpse at the inner workings of Russia’s new integration project.

The Eurasian Economic Union is an extension of various integration projects between the countries of the former Soviet Union beginning with the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), Eurasian Economic Community, and Eurasian Customs Union. From the Western perspective, the EEU is often framed as a Russian imperial project, though in the region there are multiple meanings and justificatory frameworks tied to the participation of the non-Russian countries (Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan). From the perspective of migration and labour market integration, the agreement is far more radical than anything that has existed since the fall of the Soviet Union. In many ways the EEU creates one of the most integrated labour markets in the world, clearly taking a page from the EU, though its provisions have been so far hardly realised in practice. Migration in the Eurasian region has long been dominated by informal processes that have little to do with the policies that aim to regulate them, and the EEU has done little to change the situation. In order to manage disparate goals at the domestic and international levels, member states do not fully implement EEU commitments into domestic law, leaving migration flows in the informal sector outside official data, and consequently out of the public eye.

This article looks at the gap between EEU obligations set out in the treaty text, domestic immigration laws and procedures in Kazakhstan and Russia, and migrant experience with state regulations. In order to assess these gaps, I consider government and legal texts, interviews with officials, diaspora leaders, and migrant rights activists in Russia and Kazakhstan. Media reports and official immigration statistics are also included in the analysis. These gaps serve strategic goals of member states because they allow countries to formally agree to EEU commitments while keeping domestic policy underdeveloped or bureaucratically unwieldy, which serves to keep the numbers of migrants who are officially taking advantage of the treaty provisions low.

The Ukrainian Crisis and Economic Downturn in Eurasia

The EEU migration system was profoundly impacted by the economic downturn in Russia that resulted from the crisis in Ukraine. In response to the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, Western countries imposed sanctions that compounded the economic difficulties Russia was already facing due to falling oil prices, sending the country into negative GDP growth (World Bank 2015, Dreyer and Popescu 2014). Beginning in August 2014, the rouble began to lose hold against the dollar and by December 2014 had fallen to half of its value.

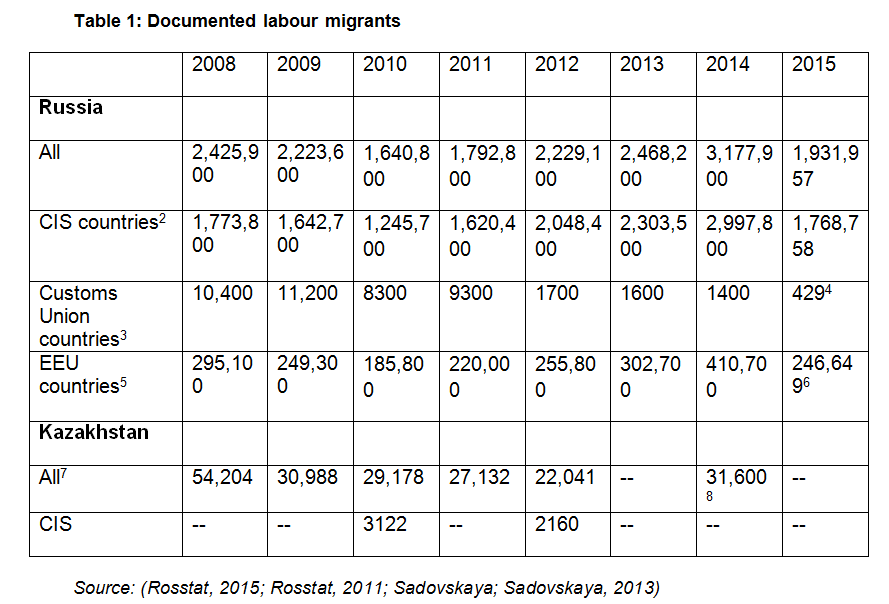

At the same time, migration rates began to decline. The Russian media was especially keen to announce that migrants were leaving Russia as a result of the economic downturn. More specifically, the media reported lower numbers of documented labour migrants than in the immediately preceding years. For example, compared with 3.2 million documented labour migrants in 2014, 2015 saw a reduction of 40 per cent to 1.9 million legal labour migrants.

While media reports focused solely on economic explanations for the fall in the number of labour migrants, a major change in Russian migration policy also contributed significantly to the ability of migrants to achieve documented status. It is the combination of these factors together that contribute to a fuller picture of migration. While economic factors are a primary driver of migration flows, policies and their implementation determine how easily labour migrants will be able to regularise their status. While states often have little control over external economic shocks, their greatest point of control over immigration is the proportion of migrants who will be diverted to the informal sector through policies and their implementation.

Policy changes affected all migrants from the Commonwealth of Independent States countries who were not part of the EEU (including major sources of immigration: Tajikistan and Uzbekistan). New policies that took effect on 1 January 2015 required migrants to complete a standard set of procedures including passing a language, history, and legal norms exam in addition to undergoing a number of bureaucratic procedures, all within 30 days of arrival. These tasks proved difficult for migrants to complete within the allotted time. As a result, many migrants shifted into the informal labour market, demonstrating a veritable law of migration, according to which when policy becomes more restrictive, previously temporary or circular migration flows become more permanent (though in this case unofficial) stocks (Hollifield, Martin and Orrenius 2014; Martin P. L. 2014; Massey and Pren, 2012).

Yet, immigration trends indicate that migration policies are secondary to economic forces in determining migration flows. According to a migrant rights activist from Moscow, there was indeed an outflow of migrants as a result of recession in Russia, but it was temporary, lasting six months or so. Compared to the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, which also saw decreased migration flows to Russia that recovered only within a few years, the 2014 recession had a relatively short-term impact on migration flows. In 2014, the rouble crisis began to affect Russia’s Central Asian neighbours to the point that Russia quickly returned to its place as a comparatively advantageous destination for work and earning potential. Despite continued recession, both the supply of migrants and the demand for their labour remains robust in Russia, even if migrants are not able to legalise their status. The same is true in Kazakhstan, a secondary destination for migrants from Central Asia. Kazakhstan experienced significant currency devaluation in 2015 (losing nearly half of its value) but was able to stave off recession. The comparatively better economic position, combined with significant state construction projects requiring low-skilled labour (such as EXPO 2017), has increased Kazakhstan’s relative importance as a migrant destination in the Eurasian region.

Labour Migration Trends, Policies, and Barriers to a Common Labour Market

In the context of economic downturn and policy change, the entry into force of the EEU created a number of migration-related puzzles. Both in the Russian case (Schenk 2013) and more widely in the experience of migration countries such as Spain, Japan, South Korea, the US immigrant receiving states often erect protectionist policies such as reduced quota, hiring bans, and ‘return bonuses’ or pay-to-go schemes (cash settlements to migrants who agree to leave the country) in response to economic crisis (Fix, et al. 2009; Martin 2009; Ybarra, Sanchez and Sanchez 2016; Lopez-Sala 2013). Given these general principles of migration policy-making, the main puzzle herein concerns the decision to maximally open the labour market in a time of recession. A further puzzle is why open labour market policies would be pursued at the same time as other major migration policies were becoming increasingly closed and securitised.

In Russia, reforms of labour permits (called ‘patents’) beginning on 1 January 2015 for CIS citizens are a key example of migration restrictions that run in a counter direction to the EEU common labour market. In both Russia and Kazakhstan, we see increasingly securitised migration rhetoric (framing migrants as a threat), which both creates and reinforces anti-migrant attitudes in society, as well as policies and institutional reforms that follow the rhetoric. For example, in April 2016, Russia transferred the responsibility of migration regulation and policy development from the independent Federal Migration Service into the Ministry of Internal Affairs. In June 2016, Kazakhstan created a National Bureau of Migration within the Ministry of Internal Affairs specifically to address security-related migration problems including uncontrolled migration and illegal settlements.[1]

The fact that EEU migration policies run counter to the general migration orientation in Kazakhstan and Russia must be carefully managed by these countries’ governments in order to manage the dual goals of regional integration (to serve geopolitical aims) and protecting local labour markets (to satisfy domestic populations). There are two primary ways that this management can proceed: in data collection and reporting, and in (non-)adherence to EEU agreement principles through implementation into domestic law and practice. Both of these mechanisms are instrumental in determining and reflecting how many migrants are able to formalise their labour status.

It is difficult, though not impossible, to measure the real impact of the EEU on migration trends because of a number of data deficits. First of all, data is scarce, and in some cases completely absent or unavailable from the government sources that collect them. Data in Russia are the most developed and publically available in the region, while Kazakhstan is marked by a remarkable dearth of data in spite of its position as the second largest migrant destination in the region. Second, official government data from the statistical services is typically issued with a significant delay. Therefore, at the time of writing, data for 2015 has yet to be released (see Table 1). The only available data for 2015 comes from Russia’s General Directorate for Migration (the former Federal Migration Service). These data hint at a third problem: many labour migrants do not appear in the official statistics. This is not only because of irregular migration, but also due to the potential for labour migrants to be counted in different migration categories. As a result, even prior to the EEU labour migrants were underestimated for a variety of reasons.

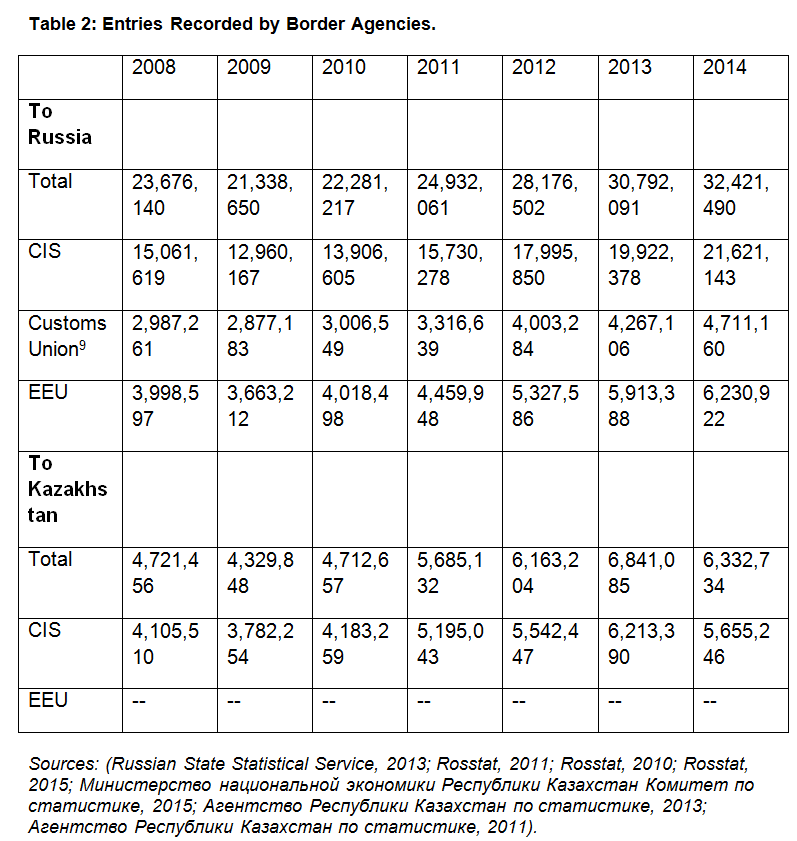

One of the primary reasons why labour migrants are underestimated is because there are a variety of preferable legal statuses they can pursue that provide more secure working conditions. These include temporary or permanent residence permits, or citizenship, all of which give migrants the right to work on the same basis as native-born Russian citizens, without preventing the circular movement of migrants between Russia and their home country. Furthermore, beginning as early as 2012, Kazakhs and Belarussians disappeared from labour migration statistics because they were given free access to the Russian labour market within the framework of the Eurasian Customs Union (a precursor to the EEU). Data on border crossings helps to capture some of the missing labour market data by showing the volume of foreigners entering a particular country (see Table 2). These data include all foreigners crossing the border into the country for any reason (e.g. tourism, work, study, etc.). They indicate that in the years that show decreasing documented labour migration in the Customs Union, the number of border crossings increased, suggesting that labour movement in the region remained robust yet uncaptured in the official statistics.

Once the EEU came into force, migrants from Kyrgyzstan and Armenia also began to disappear from labour migration statistics. Until August 2015, Kyrgyz citizens could not take advantage of the EEU provisions, and were thus counted according to previous procedures (i.e. patents). Once EEU procedures took over, data collection became problematic. A primary reason for this is that migrants did not know the proper procedures for registering their presence and work. For labour migrants in Russia the entry into force of the EEU was eclipsed by new patent regulations discussed above. The labour permit reform was accompanied by a major campaign by the government to create state-run migration centres that could consolidate the profits of issuing patents.[2] In the wake of these activities, the regulations for EEU migrants were virtually neglected, and so were any efforts to inform migrants of their responsibilities. Several of the government-affiliated migration centres advised EEU migrants simply that they did not need to complete procedures for getting a patent or obtain permission to work. While this is technically true, it neglects a very important aspect of the EEU provisions for the free movement of labour.

Article 96 of the EEU agreement importantly defines employment as ‘activities performed under an employment contract’. This short definition has proved to be the greatest challenge both for migrants’ ability to realise the benefits of the EEU common labour market, and for governments to collect data on the work of migrants within the framework of the EEU. Though the Russian migration services began to collect data on the number of contracts submitted (reflected in Table 1), this was a new procedure and therefore there are no comparative data points to date.[3] In Kazakhstan, contracts are submitted to the migration police, but there are simply no data available from this agency.

A larger problem with employment contracts is that low-skilled labour migrants (which are far greater in numbers than high skilled migrants) do not traditionally have contracts. The primacy of contracts for migrant workers is an important development because of its historical disuse marked by the small number of migrants who have labour contracts. Because of this, linking a migrant’s status to a formal employment contract could put the legal status of EEU migrants in jeopardy. Reports from migrant advocates and activists in Russia indicate that many Kyrgyz workers continue to work in Russia without a contract, either because they do not believe (or know) it is necessary, or because their employers do not want to provide one. In Russia, many employers have been reluctant to sign contracts since it would formalise the working relationship thereby obligating them to pay taxes and social insurance (Tyuryukanova 2008, Zayonchkovskaya 2007a).

A 2015 survey of Kyrgyz and Uzbek labour migrants in five regions of Kazakhstan showed that 79 per cent of Kyrgyz migrants surveyed did not have a labour contract.[4] While these survey results reflect pre-EEU procedures, it indicates significant potential problems for migrants (and employers) who are not accustomed to signing employment contracts. Furthermore, only 44 per cent of migrants reported that their employers provided residence registration (a necessary step in confirming legal status), while presumably the remainder registered themselves. This indicates that a majority of employers offer minimal support to the migrants they hire and may be unwilling to sign employment contracts if it obligates them to pay additional taxes.

A further issue is that in some cases national legislation does not yet provide the benefits promised in the EEU agreement. A case in point is the residence registration procedures for citizens of Kyrgyzstan in Kazakhstan. Despite Kyrgyzstan’s entry into the EEU in August 2015, Kazakhstan did not make any legal changes in support of the free movement of labour until February 2016 when the registration period for Kyrgyz citizens coming for the purpose of work was extended from five to 30 days (citizens of Russia had prior been granted 30 days to register regardless of their purpose of stay, on the basis of a bilateral treaty). Only migrants who have declared their purpose of visit as work on their migration card are eligible for this extension.[5] Family members of migrants who will not be working (and thus have listed their purpose of visit as ‘private’) must register within five days.[6] This is in contravention of the EEU agreement, which states that ‘Nationals of the Member States entering the territory of another Member State for employment and their family members shall be exempt from the obligation to register within 30 days from the date of entry’. The Kyrgyz consulate in Kazakhstan indicates the issue of extending a longer registration period for family members is still being negotiated between the governments, though a representative of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Kyrgyzstan reported this is simply an issue of Kazakhstan’s compliance with its obligations and there is nothing to discuss between the two countries. Consequently, Kyrgyzstan has threatened to shorten the period of stay for Kazakhstani citizens in Kyrgyzstan in retaliation for the lack of commitment to EEU norms.[7]

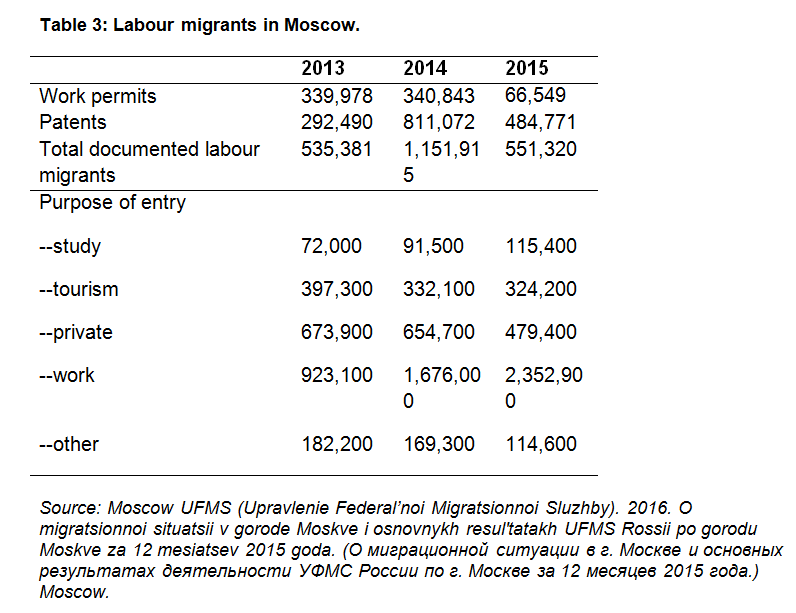

Both in Kazakhstan and in Russia migrants must declare their purpose of visit as ‘work’ on their migration card as they enter the country. Kazakhstan does not report the number of migrant cards received or the purpose of visit, and Russia only began reporting nationwide data on the category of work as purpose of visit in 2015. Various regions of Russia have published data on migrants entering with the stated purpose of work that includes several years of comparative data. Data from Moscow is informative, since it is the largest migrant recipient in Russia. Table three shows that the number of migrants arriving to Moscow with the declared purpose of work increased substantially. This is owing in part to the 1 January 2015 rule that patents could only be issued to CIS citizens with a migration card that specifies work as the purpose of visit.

Yet, it is also clear that the number of documented migrants is more than four times lower than the number of migrants who specify work as their purpose of entry on their migration card. The data in Table 3 do not include EEU migrants, since Moscow does not issue the number of work contracts received by EEU citizens, reinforcing the idea that EEU migration has been neglected in comparison with other categories of migrant workers. Yet, since Table 1 shows that across all of Russia fewer than 250,000 EEU migrants legalised their working status in 2015, even if all 250,000 were in Moscow and added to the 550,000 other documented workers, there would only be around 800,000 legal migrant workers in Moscow. This number is still far fewer than the 2.4 million workers arriving to Moscow with the intention to work. We can conclude from these data that because there are many more migrants entering who intend to work than are recorded as documented labour migrants, not only do data collection procedures underestimate the number of labour migrants in Russia, but bureaucratic procedures act as barriers to realising full legal status.

Conclusion: Priorities vs Realities

In practice, the Eurasian Economic Union is a political project that has a primary aim of meeting symbolic geopolitical goals rather than affecting concrete policy change. In order to meet domestic goals, while still pursuing integration, member states keep from fully implementing EEU obligations at the domestic level. As long as the economies are relatively strong, migrants continue to come to Kazakhstan and Russia. Yet, when policies are underdeveloped or bureaucratically challenging, EEU migrants are unable to take advantage of treaty provisions, remain in the informal sector and are not captured in official data.

Kazakhstan’s reluctance to implement EEU obligations could indicate several things. One potential explanation is that the status quo (which includes a high proportion of informal migrants) is beneficial to employers and others who profit from migrants and their informal status, while it keeps the number of official migrants low. Because the immigrant flows to Kazakhstan are smaller than in Russia, they have not provoked a sense of crisis among the public or state officials, and therefore immigration is not high on the agenda of priority reforms.

In the Russian case, the neglect of EEU migrants can be explained by several factors. One is the relatively smaller number of migrants coming from EEU countries, and therefore less urgent attention given to developing procedures and disseminating information for these migrants. This is exacerbated by the timing of reforms, since Russia concurrently adopted dramatically different procedures for non-EEU migrants that took much of the attention away from EEU migrants. Second, the EEU labour market reforms were controversial in Russia, causing the public to fear a flood of new migrants with no control mechanisms to protect the domestic labour market. Neglecting EEU migrants serves to keep official numbers low, which is more politically palatable to the public.

In the area of migration, policy development is further impeded by the fact that there are no high-level agreements on the politics of migration. Prior to the agreement’s entry into force, Kazakhstani President Nursultan Nazarbayev expressed his desire for the union to remain non-political and by his estimation this meant that certain issues such as migration and border control should not be under the purview of the EEU (Popescu 2014). In the hyper-politicised aftermath of the Ukraine crisis, migration issues (including the protection of citizens and ethnic compatriots abroad) could very well be seen as vital issues of sovereignty that states are unwilling to have decided by a supranational organisation. Because the countries of the EEU frequently draw parallels between Europe and their own experience, any lessons learned from Britain’s referendum to leave the European Union, largely motivated by migration issues, could contribute to a greater reluctance on the part of EEU countries to further deregulate migration arrangements.

Insofar as the EEU affects the sovereignty of the states involved, it cannot avoid creating political conflicts within and between member states when sensitive issues are at stake. Despite Nazarbayev’s hopes to limit the political content of the union, the nature of a grand-scale integration programme will necessarily raise questions that can only be answered politically. The current situation, where migration policy is vaguely defined, leaving member states to rely on national legislation and practices on the ground that do not meet EEU obligations, is one way to avoid potential conflict at the top political levels. Yet, avoiding high-level conflict will inevitably create tensions in the labour markets, as migrant workers’ experience will not proceed according to the legal rights afforded them in the EEU framework. If new member states are being attracted to EEU membership with the promise of an open labour market, the realities of migrant experience on the ground is likely to be disappointing. In this context, sending states that are dependent on migrant remittances and serious about developing policies for their citizens abroad may find EEU membership less than what they bargained for.

Notes

[1] https://tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_news/mvd-rk-poyavitsya-natsionalnoe-byuro-voprosam-migratsii-296329/

[2] Numerous fees are involved in obtaining a patent (for a Russian language exam, medical exam, notarising and translating documents, etc.) typically totaling at least 10,000 RUB.

[3] The Eurasian Economic Commission alternatively looks at migrants registered with the national pension funds to extract data on labour migration.

[4] Survey deployed by the author.

[5] This information is not provided by the migration police, where registration documents must be processed, but rather is only available at the Consulates of EEU countries. The migration police do not have a website, nor are there any instructions on any Kazakhstani government website explaining registration procedures.

[6] http://tengrinews.kz/sng/kazahstan-uprostil-registratsiyu-trudovyih-migrantov-289703/

[7] https://www.zakon.kz/4797186-v-kazakhstane-sokratilis-sroki.html (Accessed 30 June 2016).

References

Агентство Республики Казахстан по статистике, Кaзахстан в цифрах, Astana, 2011.

Агентство Республики Казахстан по статистике, Брошюра «Казахстан в цифрах», Astana, 2013.

Министерство национальной экономики Республики Казахстан Комитет по статистике. Брошюра «Казахстан в цифрах». Astana, 2015.

Dreyer, I., & Popescu, N. Do sanctions against Russia Work? European Union Institute for Security Studies, 2014.

Fix, M., Papademetriou, D. G., Batalova, J., Terrazas, A., Lin, S. Y.-Y., & Mittelstadt, M. Migration and the Global Recession. Migration Policy Institute, 2009.

Hollifield, J. F., Martin, P. L. and Orrenius, P. M. “The Dilemmas of Immigration Control,” in J. F. Hollifield, P. L. Martin and P. M. Orrenius, Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective, 3rd edition, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014.

Lopez-Sala, A. “Managing Uncertainty: Immigration Policies in Spain during Economic Recession (2008-2011),” Migraciones Internacionales 7, no.2 (2013): 21-69.

Martin, P. “Recession and Migration: A New Era for Labor Migration?” International Migration Review, 43, no.3 (2009): 671–691.

Martin, P. L. “Germany,” in J. F. Hollifield, P. L. Martin, & P. M. Orrenius, Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective, Third Edition, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014: 224-250.

Massey, D. S. and Pren, K. A. “Unintended Consequences of US Immigration Policy: Explaining the Post-1965 Surge from Latin America,” Population and Development Review, 38, no.1 (2012): 1–29.

Popescu, N. “Eurasian Union: The Real, the Imaginary and the Likely,” Chaillot Papers, No. 132. Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies, September 2014.

Rosstat, Chislennost’ i migratsiya naseleniya Rossiiskoi Federatsii, 2010.

Rosstat, Chislennost’ i migratsiya naseleniya Rossiiskoi Federatsii, 2011.

Rosstat, Trud i Zanyatosti, 2011.

Rosstat, Chislennost’ i migratsiya naseleniya Rossiiskoi Federatsii, 2015.

Rosstat, Trud i Zanyatosti, 2015.

Russian State Statistical Service, Chislennost’ i migratsiya naseleniya Rossiiskoi Federatsii v 2013 godu, 2013.

Sadovskaya, E. (n.d.). Законная трудовая миграция в Казахстан, Demoscope.ru, http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2014/0583/tema03.php

Sadovskaya, E. Mezhdunarodnaya Trudovaya Migratsiya v Tsentral’noi Azii v nachale XXI veka. Moscow: Vostochnaya Kniga, 2013.

Sadovskaya, E. Законная трудовая миграция в Казахстан. Demoscope.ru, 2014, http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2014/0583/tema03.php

Schenk, C. “Controlling Immigration Manually: Lessons from Moscow (Russia),” Europe-Asia Studies, 65, no.7 (2013): 1444-1465.

Tyuryukanova, E. “Labour migration from CIS to Russia: New Challenges and Hard Solutions,” presented at ‘Empires & Nations’ 3-5 July 2008 in Paris, France.

World Bank. Russia Economic Report: The Dawn of a New Economic Era? Moscow: Macroeconomics and Fiscal Management Practice of the Europe and Central Asia Region of the World Bank, 2015.

Ybarra, V. D., Sanchez, L. M. and Sanchez, G. R. “Anti-immigrant Anxieties in State Policy: The Great Recession and Punitive Immigration Policy in the American States, 2005–2012,” State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 16, no.3 (2016): 313–339.

Zayonchkovskaya, Z. “Novaya migratsionnaya politika Rossii: vpechatliayushiye resultati i novie problemi [New Immigration Policy of Russia: Impressing Results and New Problems]” 2007, http://migrocenter.ru/science/science027.php

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- European Union Migration Law and Policy

- Observations on Migration in the Twenty-First Century: Where to from Here?

- Opinion – Refugee Hierarchy in Western Responses to the Ukrainian Crisis

- Opinion – A New Pact on Migration and Asylum in Europe

- Introducing Critical Perspectives on Migration

- What Shapes the Narratives on Internally Displaced People in Dnipro Media?