The tragedy of the migrant and refugee boat, reportedly carrying around 600 people, that capsized in the Mediterranean off the coast of Rosetta, Egypt in September 2016 was another dramatic scene to be added to the numerous and overwhelming images of migrants crammed on boats, risking their lives while crossing to Europe for the hope of a better life. Incident has followed incident, leaving behind a prominently increasing number of deaths including women and children, exacerbating human tragedies, and putting pressure on policy makers to respond to the complex challenge of irregular maritime migration. Indeed, boat migration to Europe across the Mediterranean is not a new phenomenon, yet it has been growing steadily recently and is not expected to decline in a near future due to the ongoing crises in Africa and the Middle East which are prompting outflows of migrants and refugees. Although it is not the only route for irregular migration to Europe, boat migration has recently captured more attention due to the tremendous human tragedies it involves and the complexity of addressing it. The issue of fatalities related to Mediterranean crossings has become an urgent matter and politically controversial. Information about how many have died attempting to cross the southern external borders of the European Union (EU) are rare and not accurate. Different political and institutional actors have different stakes in the answer to this question and statistics are often used to justify funding and intensification of border control (Last and Spijkerboer 2014, 85). This research paper therefore revisits the issue of border related fatalities in the Mediterranean. It addresses the following question: Is there a relation between border control policies and the fluctuation of fatalities at the Mediterranean? To answer this question, the paper examines the recent case of the increased number of fatalities in the Mediterranean in 2016 compared to the numbers in 2015 despite a notable decrease in the number of crossings from last year. The total number of fatalities in the Mediterranean since the beginning of 2016 through 19 December has reached 4,901, this is 1,1124 more deaths than the total numbers of last year, whereas the number of arrivals sharply decreased to reach 358,156 migrants in 2016 through 19 December compared with 1,007,492 total arrivals in 2015 (IOM 2016a). Puzzled by these numbers, the paper addresses the following sub-research question: If boarder control policies have managed to decrease the number of migrants who arrived in Europe, why has 2016 been the deadliest year for migrants crossing the Mediterranean?

I argue in this paper —along the line with the common assumption in the literature— that there is a relation between border control policies and fatalities in the Mediterranean. Intensifying border control policies will push migrants to resort to other routes that are longer and more dangerous and hence the risk of losing their lives is higher. The hypothesis of the paper is the more border control policies or practices are introduced, the more fatalities at sea. I will test this hypothesis in relation to the Central Mediterranean case in 2016, in particular in relation to two major border control policies that were implemented in 2015 and early 2016, namely the EU-Turkey agreement and the change in search and rescue policies. It is extremely painful to view human tragedies as simply an increase or decrease in numbers; yet this paper aims at unpacking these numbers in relation to one of the main variables in whole boat migration mechanism, namely border control policies. Examining this relation should be extremely important for EU policy makers (if willing and interested) to assess border control policies particularly since the beginning of the so-called EU refugee crisis. It is also important to understand what border control policies actually do; they might stop migrants from reaching Europe but do they stop migrants from taking the leaky boats?

There is a common assumption in media reports and some of the reports of human rights organizations about a causal relationship between policies and fatality rate in the Mediterranean[1]. This relation, however, has hardly been examined as will be indicated in the literature review section. This research paper does not claim to fill in this gap in the literature, as it is beyond its scope. The objectives of the paper are to highlight this gap and the need for such studies; and to add a modest contribution to the literature by examining the relation between fatalities and border control policies in the Central Mediterranean route in 2016.

Background Overview

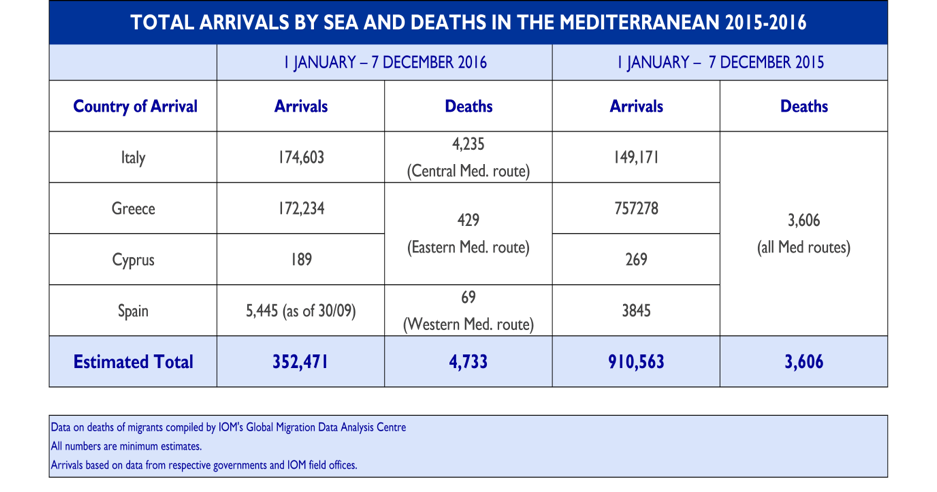

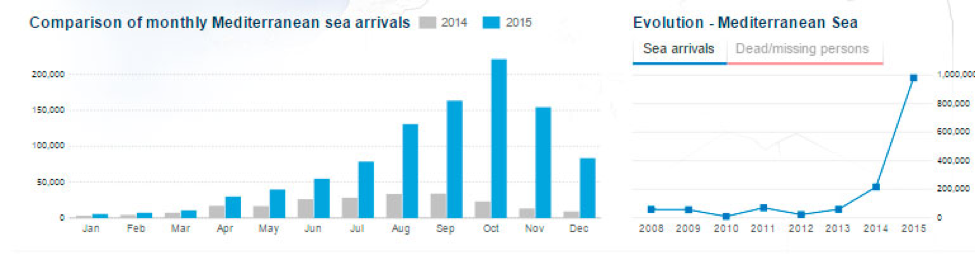

This section briefly presents background data on the estimates of arrivals and deaths in the Mediterranean since 2013, i.e. since the beginning of the EU-refugee crisis. According to Frontex- the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, “illegal border crossing” at the EU external borders increased sharply in 2013, rising to over 107,000 from 75,000 in 2012, with Syrians, Eritreans and Afghans being the most commonly detected nationalities (Frontex 2014). The increase continued in 2014 to over 204542 arrivals in Italy and Greece (IOM 2016b). The peak was in 2015 with over 1 million asylum-seekers and migrants crossed the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe, an unprecedented influx mainly driven by the movement of Syrians, Afghans and Iraqis entering Europe through the Greek Islands from Turkey. The number of maritime arrivals in 2015 was more than 35 per cent higher than in 2014, and over 14 times greater than in 2011 (Frontex 2015). In 2016, the total number of crossings up to 19 December 2016 has decreased dramatically to reach 358,156, i.e. around 64 per cent lower than the overall arrivals last year (IOM 2016a).

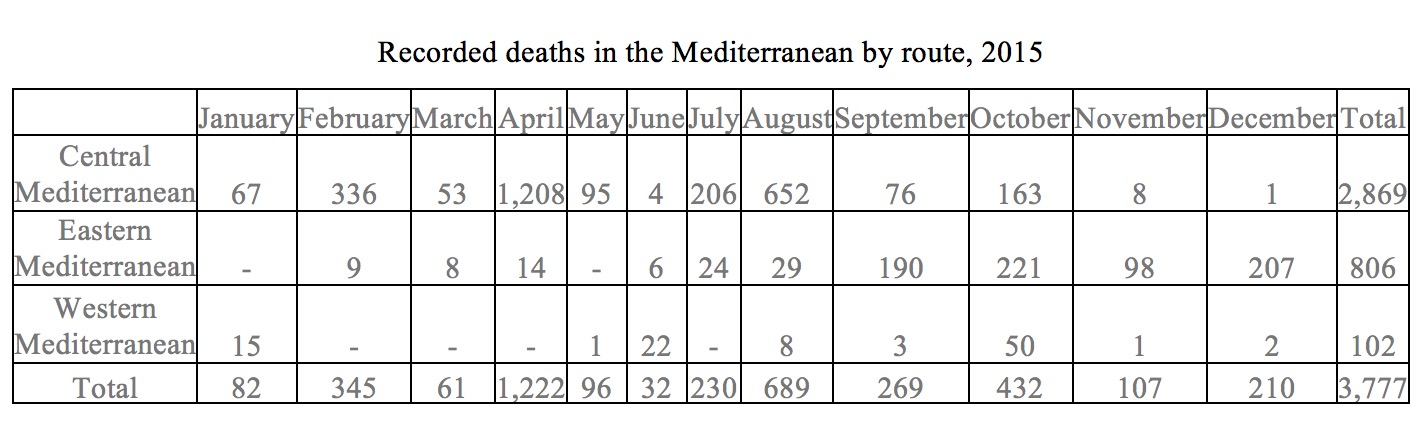

The fatality rate in 2015 reached at least 3,770 dead or missing at sea, which is 15 per cent higher than the estimated 3,280 deaths in 2014. Roughly 77 per cent of deaths in 2015 occurred in the Central Mediterranean, while about 21 per cent occurred in the Eastern Mediterranean (Brian and Laczko 2016, 6). According to the European Parliament, “the death toll would have been much higher if it were not for extensive search-and-rescue operations that saved hundreds of thousands of lives over the past two years, including through Italy’s Mare Nostrum in 2014, Frontex’s Joint Operation (JO) Triton and JO Poseidon Sea, as well as national navies and coast guards, merchant and other ships” (Brian and Laczko 2016, 6).

In October 2016, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNCHR) announced that this year has been the worst in terms of the number of fatalities among refugees and migrants crossing the Mediterranean. With just few days remaining in 2016, IOM reports on 19 December that 4,901 migrants and refugees are dead or missing presumed drowned in the Mediterranean (IOM 2016a). This year one migrant has died for every 73 migrants who arrive safely. In 2015 the figure was one death for every 267 successful crossings (IOM 2016a).

A recent report by the IOM concludes that the Mediterranean Sea continues to greatly outweigh other regions in terms of the number of people who are recorded missing and/or dead during the process of migration with the majority of the fatalities concentrated in the Central Mediterranean route (IOM 2016c). This year as of 19 December, there are 4,403 deaths in the central Mediterranean route (mainly from Libya and Egypt to Italy and Malta sea border), compared to 429 fatalities at the Eastern Mediterranean (From Turkey to Greece and Cyprus) and 69 fatalities in the Western Mediterranean (From Morocco to Tunisia) (IOM 2016a).

To summarize this section, the number of irregular migrants arriving by sea to Europe has been increasing since the beginning of the refugee crisis in 2013. The year 2015 was the peak of the number of arrivals in Europe and the year 2016 has been the worst in terms of fatalities in the Mediterranean. The Central Mediterranean route remains the most perilous route to Southern Europe.

Defining Terms

One of the challenges of doing research on issues related to migration, particularly irregular migration, is definitions as there is hardly consent on defining certain concepts. In this section, I will define the concepts that will be used in the paper. I will not get into the controversy around defining certain concepts, but rather I will focus on presenting in what sense these concepts will be used in the paper.

Irregular Migration

Irregular migration, in broad sense, refers to “movement that takes place outside the regulatory norms of sending, transit and receiving countries” (IOM 2015). There are a number of expressions, such as “irregular”, “illegal”, “undocumented”, “unauthorized”, and “clandestine”, which are used sometimes interchangeably to describe migrants who enter a country illegally, overstay a legal residence permit in a country, and/or break the immigration rules in a way or another at any stage of the immigration process (Triandafyllidou 2016). The term “illegal migration”, however, is quite controversial as scholars argue that the adverb “illegal” associates this type of migration with criminal behavior and should be avoided. Therefore, the term “irregular migration” has increasingly replaced illegal migration in its border sense (Triandafyllidou 2016).

For the purpose of this paper, the term irregular migration (also referred to as boat migration) is used to refer to the act of leaving a sending country in an attempt at reaching a destination country by sea not only without the necessary documents and authorization but also through illegal ways (illegal refers to the ways not to the people) that involve dealing with smugglers.

Irregular Migrants

Another challenging aspect of irregular migration is how to define irregular migrants. The problem of irregular migration is that it involves what is referred to as “mixed flows”. A term introduced by the UNHCR to refer to the flows encompassing migrants who have the choice to leave, such as economic migrants leaving to improve their lives, and refugees and forced migrants who are escaping different types of persecution, armed conflicts or other forms of violence. These flows “make use of the same routes and means of transport to get to an overseas destination […] These mixed flows are unable to enter a particular state legally, they often employ the services of human smugglers and embark on dangerous sea or land voyages, which many do not survive” (UNHCR 2016). The term irregular migrants, in this paper, is used to refer to mixed flows of migrants including refugees and other forced migrants, in addition to economic migrants as well.

Refugee Crisis

Refugee crisis or Europe Refugee/Migrant crisis is a loose term that has been frequently used to refer to the surge of refugees and migrants arriving in Europe from southern Mediterranean countries in the after mass of the Arab Spring uprisings. The escalating war and conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan among other countries have resulted in thousands of refugees and migrants arriving at Europe’s shores or borders (Hampshire 2015). The crisis was culminated in 2015 when more than 1 million refugees, migrants and asylum seekers reached Europe. Not only that the scale of the recent migration flows to Europe is unprecedented, but also it is also enormously complex as the influxes encompass mixed flows. The crisis has poised a challenge to the EU to respond to these flows (Hampshire 2015). It also has a number of implications on EU and on its institutional architectures but this is beyond the scope of this paper. The term refugee crisis is used in this paper to refer to the unprecedented flows form the southern Mediterranean countries that have arrived in Europe in the after mass of the Arab Spring and reached its peak in 2015.

The literature review

Among the challenges of undertaking this research paper is the shortage of literature that studies the relation between border control policies and fatalities at the Mediterranean Sea. The paper is looking at the case of Central Mediterranean in 2016 which makes it more challenging to find relevant literature. The literature review section, therefore, is divided into two parts: the first part highlights the recurrent themes in the literature on irregular migration or “boat migration” in the Mediterranean which will help build-up the research argument and the second part reviews the available literature on border control policies and fatalities in the Mediterranean highlighting the gap in the literature.

Irregular Migration in the Mediterranean: Recurrent Themes

The first recurrent theme is that the Mediterranean Sea route for irregular migration to Europe is anything but new (Fargues & Bonfanti 2014, Vallet 2014, Monzini 2007, Morehouse and Blomfield 2011, de Haas 2013). The phenomenon of the so-called “boat migration” started to become more recurrent with the introduction of Schengen visas in 1991, free entry into Spain and Italy was blocked, and North Africans, particularly Moroccans, Algerians and Tunisians, who could not obtain visas started to cross the Mediterranean illegally in small fisher boats (de Haas 2015a). It was in the beginning of the 1990s that Southern European countries such as Italy and Spain realized that they became much sought-after destinations and they started to react by imposing border control policies. With more restrictive policies on immigration and following the collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, the number of irregular migrants progressively increased arriving from different regions of the world: the Balkans, the Middle East, Africa and China. Consequently, smuggling by sea became a structural part of the wider market of irregular migration. Italy along with Spain and Greece has become the main destination countries in Europe for these kinds of migration. (Monzini 2007, 3; Fargues and Bonfanti 2014).

Fargues and Bonfanti (2014) present data of a total number of 840,904 migrants recorded by the border authority entering the EU illegally by sea covering the period from 1 January 1998 till 30 September 2014. The annual average numbers stood at 44,000 migrants until 2013. The noticeable peaks were recorded in 2006 and 2011 which the study attributes respectively to the opening of a new route through Mauritania and later on Senegal to the Canary Islands, and the Tunisian uprising in 2011 (p. 3). These numbers dramatically increased with the refugee crisis as indicated in the background section.

A second recurrent theme in the literature is that the relation between border controls and the places of disembarkation and irregular migration routes. Fargues and Bonfanti (2014) highlight the relation over years between border controls and the places of disembarkation and routes. The study concludes that as “a general rule, each time a route became more efficiently controlled at embarkation or disembarkation, new routes circumventing controls have been invented” (3). De Haas (2015b) shows that boat migration to Spain from North Africa countries in 1990s started on a small-scale through operations run by fisherman. When Spain, however, started to introduce more sophisticated, “quasi-military border control systems” along the Strait of Gibraltar, smuggling professionalized and migrants started to cross not only from Morocco and Tunisia, but also Algeria, Libya to Italy and Spain, and from the West African coast towards the Canary Islands (Para. 4). A recent study, undertaken by the IOM, illustrates how routes for irregular migration across the Mediterranean area to the EU fade in and out of use over time. The study clearly shows that as new strategies are being introduced by border agencies in response to irregular entry, migrants and facilitation networks find out new routes to circumvent obstructions (Brian and Laczko 2014).

The third recurrent theme is that the sea routes to Europe have always been increasingly lethal. Fargues and Bonfanti (2014) present data that show that from 1998 till 30 September 2014 around 15,016 numbers lost their lives at sea in addition to the uncounted deaths. These data are compiled from NGOs’ and media reports according to the study. Grant (2011) postulates that the total number of migrants and refugees who have tried to cross the Mediterranean borders in the last decade is unknown, as well as the numbers who died on the journey. It is, however, estimated that as many as one out of four persons attempting to reach Europe by sea had perished during the trip (Grant 2011). The International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) estimated that at least 10,000 died in the Mediterranean trying to cross to Europe in the decade 1993–2003 (Grant 2011,186). Regardless of the exact number of fatalities which is difficult to track —as not all bodies are found and not all missing cases are reported— it is clear that the journey to Europe through the Mediterranean routes has been always lethal.

A fourth recurrent theme is that the EU’s response to the increasing numbers of irregular migration arriving Europe through the Mediterranean has always been intensifying border control (Vallet 2014; Fargues and Bonfanti 2014; Grant 2011). De Haas (2015a) quotes Jørgen Carling’s argument that the EU all over the years has been caught up in a vicious circle in which “increasing number of border deaths lead to calls to ‘combat’ smuggling and increase border patrolling, which forces refugees and other migrants to use more dangerous routes using smugglers’ services” (Para. 2).

Since late 1990s, the EU started to involve North African Countries in prevention and “fighting against irregular migration”, this involvement was increased within the framework of the Global Approach to Migration (GAM)[2] adopted in 2005. The involvement is carried out by several instruments including: readmission agreements of undocumented aliens; police cooperation agreement including providing surveillance to patrol the Mediterranean Sea, joint investigative and formative activities, and construction of detention centers (Vallet 2014, 13).

The EU has “externalized” its border control policies to transit and sending countries by providing them with new border posts, equipped with advanced information technology (Grant 2011, 137). In addition, Irregular migration control has been integrated into policies to address terrorism, national security and international crime, and NATO’s counter-terrorism operations in the Mediterranean have involved it in monitoring ships carrying irregular immigrants and asylum-seekers (Grant 2011, 137). Frontex, was established in 2004, to coordinate and develop European border management and work with border-control authorities of countries identified as a source or transit route of irregular migration (Vallet 2014, 14). In short, the response of the EU has always been to foster border control.

To sum up, the aim of this section is to highlight the recurrent themes in the literature on irregular migration in the Mediterranean which would help build the argument of the paper. The themes could be summarized as follows: the phenomenon of boat migration to Europe through the Mediterranean Sea is not new; the Mediterranean route has always been lethal; the response of the EU has always been to tighten border controls; and finally and more importantly whenever a new policy or practice of controlling the border is introduced, there is a new route of irregular migration to circumvent this restriction.

Border Control Policies and Fatalities in the Mediterranean

Most of the available literature on border control policies and fatalities in the Mediterranean Sea particularly since the beginning of the Refugee crisis are reports and situation updates that are issued on regular basis by international organizations such as the Internal Organization for Migration (IOM) and it Missing Migrants Projects[3], as well as the UNHCR. These reports map the movements of migrants across different routes, track the changes in the points of departure and arrival, and keep record of the number of arrivals and the number of people who died or got missed while undertaking the journey. There are also reports issued by NGOs working in Search and Rescue (SAR) in the Mediterranean and human rights organization such Amnesty International and Human Rights watch among others presenting data on fatalities and highlighting different policies undertaken by the EU. This literature is mainly descriptive of the current situation, and I will make use of it as a source of data in the analysis and discussion part.

To my knowledge, there is hardly any study that examines the relation between border control policies and fatalities. The following is a review of the available literature, which also highlights the need for such studies.

Katsiaficas (2016) examines the shifts in flows across the Mediterranean since 2008 and the complex web of interconnected variables including border control and immigration policies; changes in the origins of the flows; weather patterns; among other variables. The study concludes that migrants and refugees movements are highly adaptable; migrants and smugglers respond to changing immigration, enforcement, and visa policies, as well as a range of other conditions in origin, transit, and destination countries. The report presumes that the traffic in 2016 has been increasing along the riskier central Mediterranean route as a result of the EU agreement with Turkey and the effective closure of the western Balkan route to northern Europe, a claim that needs to be examined (see the analysis part). The study, however, does not address directly the relation between policies and fatalities. There is an assumption that as a response to restrictive border control policies, migrants risk their lives by taking more dangerous routes, yet this assumption has not been examined. Another study by Kassar and Bourgeon (2014) examines the illegal migration routes and groups across North Africa to Europe, the study underlines that boat migration studies remain biased and poorly documented; and most of the figures rely on media accounts or statistics from Frontex.

Grant (2011) addresses directly the gap in the literature on border control policies and fatalities. The author says that official efforts to examine the link between border controls and fatalities have been more systematic in the US than in Europe. Grant refers to a study that was undertaken at the request of the US Senate to examine deaths on the US border with Mexico, which concluded that “tighter border control had not deterred illegal entry, but rather diverted routes to more dangerous terrain” (140). Grant (2011) argues that unlike the US, in Europe there has been less official willingness to institute systematic data collection to examine the link between border controls and fatalities (140).

Spijkerboer (2007) presents a review of the ‘human costs’ of EU maritime border control from 1998 till 2006. The study concludes that there is a need for more reliable data to examine the link between border control policies and fatalities. Data available do not suggest that intensified border controls had led to a decrease in the number of irregular migrants. On the contrary, “migrants had simply chosen more dangerous migration routes, which exposed them to even greater risks” (131). In a recent study that Spijkerboer co-authors with Tamra Last and Orçun Ulusoy (2016), similar conclusions have been drawn. The study underlines the need for the creation of a Database for the Deaths at the Borders for Southern EU as a first step in researching the relationship between migrant mortality and European border policies (p. 17). Another important conclusion is that EU policies towards irregular migration across the Mediterranean are presently being driven by politics rather than evidences. In other words, the study concludes that there is no well-defined link between the number of fatalities and border control policies. This missing link is due to a lack of any systematic study that examines the relation between policies and fatalities at the Mediterranean borders and the lack of reliable data on the fatalities.

To conclude this section, there is a clear gap in the literature when it comes to examining the link between border control policies and fatalities in the Mediterranean. A number of assumptions are put forward in the literature but none of them has been examined.

Theoretical Framework

Conceptualizing Border Control

This research paper focuses on examining the relation between two variables in the boat migration mechanism: border control policies and the number of fatalities. It is important first to highlight the rationale behind “border control”. Guiraudon and Joppke (2001) argue that the concept of “border control” deals with migration that is happening despite and against the opposite intension of states […] Whenever there is the stated need for “control” there is the unstated admission that current policies have failed to prevent migration from happening” (2). For Waston (2009) border control policies, whether carrier sanctions, international safe havens, visa requirements, safe third country agreements, etc. are designed to ensure that refugee and asylum seekers have minimal access to the protection regimes of the Western democratic state of Europe and North America. These policies reveal the competing political, economic and humanitarian values associated with the management of international migration, and that control over borders remains an essential practice of state sovereignty and national security (p 1-2). Borders, therefore, have gained importance in the European policy makers’ “fight against trans-Mediterranean migrations” (Vallet 2014).

The purpose of border control policies have become to maintain a sense of security and identity and to provide tangible evidence that governments are doing something; “[t]he image of a fortified border becomes more important than its actual effectiveness” (Vallet 2014, 3). This could explain why “border control” has always been the solution to migration from the policy makers’ point of view. For the purpose of this paper, border control policies are used to refer to any policies or operational practices that are implemented to stop or minimize migrants’ access to Europe.

Theory & Hypothesis

The literature review section has demonstrated that there is a relation between the movement of irregular migrants and border control policies. Irregular migration routes fade in and out as a reaction to the practice of border controlling. Whenever a new policy or practice of controlling the border is introduced, there is a new route of irregular migration to circumvent this restriction. By the same token, I argue that there is a relation between border control policies and fatalities at sea, and that border control policies impact the fatalities’ rate. Border control policies do not deter migrants from crossing to Europe; on the contrary, they force migrants to risk their lives by depending on getting smuggled through longer and more dangerous routes and on leaky crammed boats, which ultimately result in more fatalities. The hypothesis of the paper, therefore, is the more border control policies or practices are introduced, the more fatalities at sea. In the next section, this hypothesis will be examined in relation to the Central Mediterranean case in 2016.

It is worth mentioning here that a counter argument could be that border control policies prevent fatalities at the sea by stopping migrants from undertaking the journey of crossing the Mediterranean. One, however, could dismiss this argument as studies (see De Haas, 2015; De Haas, Hein et al. 2016) and previous experience such as the case of Mexico and USA borders cited above in the literature review section clearly show that policies do not stop asylum seekers and other migrants from crossing borders. They rather have mainly diverted migration to other crossing points, made migrants more dependent on smuggling, and increased the costs and the risks of crossing borders.

Analysis

Case Selection & Methodology

The paper examines the Central Mediterranean route in 2016 as a case study. It is the route where most of the fatalities have been reported in 2015 and 2016 as explained in the background section. The units of analysis of this research paper are the major border control policies that were implemented in the year 2015 and early 2016, namely the EU-Turkey agreement in 2015 and the search and rescue policies and operational procedures that were introduced by the end of 2014 and intensified in 2015 and early 2016. These policies and procedures are examined vis a vis the numbers of arrivals and fatalities in 2016 comparing them with their counterparts before the introduction of these policies.

The analysis part uses numbers and data from reports published by the IOM Global Migration Data Analysis center, the UNHCR and Frontex. It should be noted that the data and numbers in these reports have been compiled from different available resources and that different methodologies have been used to maximize accuracy. Nevertheless, these data should be treated as approximates that give an indicator of the actual scale of fatalities. The irregular nature of migration makes it extremely difficult to collect data on crossing-related fatalities. The IOM published a report in 2014, entitled “Fatal Journeys: Tracking Lives Lost during Migration”, explaining how data on migrant deaths is collected and shared in different parts of the world. The report concludes that “all data sources on border deaths are limited in one way or another, so all statistics are inevitably incomplete” (Tara and Laczko 2014, 99).

Discussion

In this section, I will examine the research hypothesis against two major policies changes that took place in 2015 and early 2016; the implementation of the EU-Turkey agreement and the search and rescue policies.

EU-Turkey Agreement[4]

In October 2015, the EU and Turkey agreed on a joint action plan, commonly referred to as the EU-Turkey agreement, which aims mainly at preventing irregular migration flows to the EU. The action plan got implemented in March 2016 where the two parties agreed that from 20 March 2016 all new irregular migrants crossing from Turkey into Greek islands will be returned to Turkey; and that Turkey will take any necessary measures to prevent new sea or land routes for illegal migration opening from Turkey to the EU (EU Commission 2016).

Since the implementation of this agreement, there has been a dramatic decrease in the number of migrants crossing to Greece through the Eastern Mediterranean route[5]. According to the Second Report on the progress made in the implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement issued by the EU Commission in June 2016, “In the month before the implementation of the Statement, around 1,740 migrants were crossing the Aegean Sea to the Greek islands every day. By contrast, since 1 May the average daily number of arrivals is down to 47” (2). The fatality rate in Eastern Mediterranean has went down from 806 fatalities in 2015 to 429 as of December 20, 2016 (IOM 2016a)

A report by IOM in November 2016 presumes that the EU-Turkey agreement has led to a shift in the migration flows from Greece to Italy through the Central Mediterranean route (IOM 2016f, 2). The report shows that as of November 6, there is a significant increase of 16% (or 24,897 more individuals) than this time last year in the route to Italy. Table (1) from the IOM update Mediterranean Update on December 13 indicates that there is around 17% increase in the arrivals in Italy through the Central Mediterranean route from January 2016 till December 7 as opposed to last year during the same period. Whereas, there is around 77% decrease in the number of arrivals in Greece than last year.

I argue, however, against the presumption of this report as these data do not support the claim that the increase in the number of arrivals in Italy is due to deflection from the Eastern Mediterranean route, nor even suggest that there was a strong trend towards deflecting to the Central Mediterranean route. Looking at the top nationalities that arrived in Italy throughout 2016, Italy received a variety of nationalities, led by Nigerians (26%), Eritreans (15%), Gambians (9%) and other countries (IOM 2016f). These are quite similar to the distribution of nationalities that Italy received in 2015 (see table 2). On the contrary, the top nationalities that arrived in Greece through the Eastern Mediterranean route in 2015 and 2016 were Syrians (29%), Afghans (27%), Iraqis (17%), Pakistanis (9%), and Iranians (7%) (IOM 2016f). The fact that the distribution of nationalities in Italy did not change from 2015 and 2016 provides a strong evidence to the assumption that the 17% increase in the arrivals in Italy is not necessarily due to the deflection of migrants from the Eastern Mediterranean route, but rather due to increase in number of the nationalities that are used to cross through this route[6]. The question, therefore, remains: what are the causes for the increase of fatalities in the Central Mediterranean 2016?

To conclude this section, the findings demonstrate that there is no enough evidence to support the claim that intensifying border control policies through the EU-Turkey agreement and the closure of the Eastern Mediterranean route deflected migrants to Central Mediterranean and hence resulted in more fatalities. In fact, the data available suggest that the increase of migrants is due to increase in nationalities that are used to cross this route and not of those who were crossing through the Eastern Mediterranean route. These findings also suggest that border control policies in fact led to significant decrease of the number of crossings and hence less fatalities in the Eastern Mediterranean route. So the findings of this section do not support but rather falsify the research hypothesis.

Search and Rescue Policies

Another explanation for the increase of fatalities in the Central Mediterranean route is that it is a continuation of the increase started in 2015 due to the change in the policies of the EU search and rescue (SAR) operations, which involve locating and helping people in distress (EU Commission 2016). The priority of these operations has changed from rescuing people’s lives to securing borders and fighting smugglers.

As a response to the increasing flows arriving in Italy and increasing numbers of causalities, the Italian government in October 2013, began the operation Mare Nostrum, the “Operation is a life-saving search and rescue operation implemented by the Italian authorities using assets close to Libyan territory” (Frontex 2016). The Operation had the twofold purpose of safeguarding human life at sea, and bringing to justice human traffickers and migrant smugglers (Mare Nostrum Operation). The operation had the capability of operating permanently at sea closer to the Libyan coast and on the high seas and its budget was around 9.5 million Euros per month. This enabled the early detection and rescue of migrant boats close to the Libyan coast. The operation was success; it saved thousands of lives estimated of more than 100,000.

The operation, therefore, was criticized as being a pull factor for irregular migrants to cross the Mediterranean and for facilitation network (Death by Rescue 2016). In November 2014, the Italian government decided to end the Operation, and the EU responded by starting the Triton operation led by Frontox. Unlike Mare Nostrum Operation, the Triton operation had surveillance rather than rescue as their operational priority and they developed fewer vessels in an area further away from the Libyan coast (Death by Rescue 2016). Its operational area covers the territorial waters of Italy as well as parts of the search and rescue zones of Italy and Malta, stretching 138 nautical miles south of Sicily (EU Commission 2016b). On numerous occasions, Frontex vessels and aircrafts have also been redirected by the Italian Coast Guard to assist migrants in distress in areas far away from the operational area of Triton” (EU Commission 2016b).

The rationale behind this policy decision was to deter irregular migrants from crossing the Mediterranean as mentioned in the Frontex Assessment Report of Jo Triton 2015: “the fact that most interceptions and rescue missions will only take place inside the operational area could become a deterrence for facilitation networks and migrants that can only depart from, the Libyan of Egyptian coast with favorable weather conditions and taking into account that the boat must now navigate for several days before being rescued or intercepted” (Frontex 2015b, 2).

These policy decisions left a huge gap in the SAR capabilities close to the Libyan coast. It became apparent that in the first months of 2015, contrary to Frontext’s forecast, migrants’ crossings continued unabated. As a result of the retreat of Italy-led assets, an increasing number of migrants were left to drift for several hours or even days before being detected and before rescue means located much further away from the area where most SAR events were happening managed to reach them (Death by Rescue 2016). The number of death at sea rose dramatically in the first few months of 2015, with about 470 deaths reported as of the end of March 2015 (Amnesty 2015). As a result and to fill in this gap, the Italian Maritime Rescue and Coordination Center started to call upon merchant ships transiting in the area to carry out rescue operations, which are unfit and not equipped to carry out the large scale rescue operations involving migrants.

Statistical data show (see figure (1) and table (3) below) that in the first four months of 2015 ending Mare Nostrum did not lead to less crossings, a phenomenon that continued in 2016, it has resulted only in a higher rate of mortality (Death by Rescue 2016). While in the first four months of 2014, more than 26,000 migrants had crossed the Mediterranean and 60 deaths has been recorded, in the same period of 2015, an almost identical number of crossings has occurred, but the number of deaths had increased to 1678 (UNHCR and IOM data). The President of the EU Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker admitted that “it was a serious mistake to bring the Mare Nostrum operation to an end” (European Commission April 2015).

With the rise of the rate of fatality and after the April 2015 shipwrecks which resulted in the death of 1,208 migrants (See table 3), the EU was compelled to extend the Triton operation and triple the budget and the assets available to the operation in addition to launching the anti-smuggling operation EUNAVFOR MED close to the Libyan coast. The priority goals for these operations, however, remain surveillance and securing borders than rescuing human lives[7]. In parallel to this increase in EU funding, assets (ships and aircrafts) are being deployed by several Member States (Amnesty 2015). In addition, two non-governmental organizations, the Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) and Doctors without Borders (MSF), have also enhanced capacity for rescue operations by deploying four private vessels to assist refugees and migrants at sea (see figure (2) sums-up the search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean in 2015). Despite all these efforts the number of fatalities continues to increase in 2015 to reach 3,777, which is almost 15% higher than 2014 (3,279), when the Mare Nostrum operation was operating.

Finally, the aim of this section is not to assess the operation Mare Nostrum vis à vis the Frontex’s triton operation but rather to demonstrate using numbers and data how the change of the priority of the search and rescue policies have impacted the number of fatalities. The finding of this section reveals that one of the causes of the increased rate of fatalities in the Centeral Mediterranean in 2016 is the change in the search and rescue operations. This, however, is not the only cause for that increase other variables have not been examined due to lack of data, such as the mechanisms used by smugglers in terms of increasing the loads of the boats and the types of boats used; the departure points of the boats and/or the timing of sending out these boats. Examining these variables could have illustrated the structural causes for the increased fatalities in the Central Mediterranean. The findings of section support the research hypothesis and demonstrate that border control policies impact fatalities at sea.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper is to revisit the phenomenon of border-related fatalities at the Mediterranean, which has captured more attention since the beginning of the EU refugee crisis due to the tremendous human tragedies it involves. The paper has raised the following question: Is there a relation between border control policies and the fluctuation of fatalities at the Mediterranean? To answer this question, the paper has examined the recent case of the increased number of fatalities in the Mediterranean in 2016 compared to the numbers in 2015 despite a notable decrease in the number of crossings from last year. The paper, therefore, has addressed a sub-research question: If boarder control policies have managed to decrease the number of migrants who arrived in Europe, why has 2016 been the deadliest year for migrants crossing the Mediterranean?

By reviewing the literature on boat migration in the Mediterranean, a number of recurrent themes have emerged: the phenomenon of boat migration to Europe through the Mediterranean Sea is not new; the Mediterranean route has always been lethal; the response of the EU and European countries has always been to tighten border controls; and finally and more importantly whenever a new policy or practice of controlling the border is introduced, there is a new route of irregular migration to circumvent this restriction. The literature review has also demonstrated that there is a clear gap in the literature in studying the link between border control policies and fatalities in addition to the lack of reliable data bout the fatalities.

Along the same line of the literature review section, I have argued that border control policies impact the fatalities’ rate. Border control policies do not deter migrants from crossing to Europe; on the contrary, they force migrants to risk their lives by depending on getting smuggled through longer and more dangerous routes and on leaky crammed boats, which ultimately result in more fatalities. The hypothesis of the paper is that the more border control policies or practices are introduced, the more fatalities at sea. I have tested this hypothesis in relation to the Central Mediterranean case in 2016. I have testified my hypothesis in relation to two major policy decisions that were implemented in 2015 and 2016, namely the EU-Turkey agreement and the change in search and rescue policies.

The findings of the analysis demonstrate that 1- despite the overall decline in the number of migrants crossing the Mediterranean in 2016; there is an increase of around 17% in the number of migrants crossing through the Central Mediterranean route. 2- The findings do not support the claim that the EU-Turkey agreement and the closure of the Eastern route has resulted in deflecting migrants to Central Mediterranean. 3- The change in the priority of the search and rescue policies from rescuing lives to surveillance, patrolling borders and fighting smugglers has increased the number of fatalities. The findings have provided an answer to the puzzle of the increased fatalities rate in the Mediterranean in 2016.

The findings, however, do not provide strong evidence that support the paper hypothesis, which could be due to the limitation of the case. In answering the research main questions, one could argue, therefore, that the relation between border control borders and fatalities is not a direct one in a sense that border control policies themselves do not cause fatalities (except if these policies involve practices such as shooting at the migrants, shrinking the search and rescue operations to let them the migrants sink and die). In other words, border control policies are not the principal determinant of the fluctuation of the rate of fatalities other variables are at stake and they are beyond the control of border control policies such as pushing factors in the sending or transit countries, the migrants’ willingness to undertake a longer and more costly journey, in addition to weather conditions and mechanisms used by smuggler networks. Indeed border control policies may force migrants to risk their lives and take more dangerous routes and make them more and more dependent on smugglers to cross borders and hence leads to more fatalities. Yet border control policies are still not the direct and principal variable influencing death fatalities. In addition, these policies could also lead to the deflection of migration flows to desert routes or third countries where they would be able to cross to or stay.

The findings of this case, however, are not generalizable by any means. The research has examined only one route within an extremely limited time frame. One cannot draw general conclusions from these findings about the relation between border control policies and fatalities. These findings are only indicator of the direction of the relationship between border control policies and fatalities. This research paper also does not claim to fill in the gap in the literature on the relation between border control policies and fatalities. This requires a huge research project that goes beyond the scope of this paper. The paper objectives are to highlight this gap and the need for such studies; and to add a modest contribution to the literature by examining the relation between fatalities and border control policies in the Central Mediterranean route in 2016.

Examining the relation between border control polices and fatalities at the Mediterranean is important for EU policy makers (if willing and interested) to assess border control policies particularly since the beginning of the so-called EU refugee crisis. It is also important to understand what border control policies actually do: Do they deter people from crossing the Mediterranean to Europe and taking the leaky boats or do they lead to more fatalities at sea? There is a need, therefore, for a research project that examines all the different Mediterranean routes across different points in times. The first step to undertake such a study —as the literature suggests— is to build a Database for the Deaths at the Borders for Southern EU.

Notes

[1] See, for instance, Amnesty International Public Statement (July 2015). “A Safer Sea: The Impact Of Increased Search and Rescue Operations in the Central Mediterranean” https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur03/2059/2015/en/

[2] This approach is a comprehensive strategy to address irregular migration and human trafficking on the one hand, and to manage migration and asylum through cooperation with third countries (origin and transit) on the other (GAMM 2016). Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/international-affairs/global-approach-to-migration/index_en.htm

[3] Missing Migrants Project “tracks deaths of migrants and those who have gone missing along migratory routes worldwide. The research behind this project began with the October 2013 tragedies. Since then, Missing Migrants Project has developed into an important hub and advocacy source of information that media, researchers, and the general public access for the latest information”. Retrieved from: https://missingmigrants.iom.int/about

[4] For more information about the EU-Turkey action plan, please see “EU-Turkey joint action plan” http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-15-5860_en.htm; and “EU-Turkey statement, 18 March 2016” http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18-eu-turkey-statement/

[5] It is worth mentioning here that it is too early to assess whether or not the EU-Turkey deal will hold on and the number of arrivals will continue decreasing. It is beyond the scope of the research to assess the deal anyways.

[6] Other variables such the deterioration of the security and economic situation in the sending countries or transit country such as Libya might have led to this increase. Examining these variables is beyond the focus of this research.

[7] On 13 May 2015, the European Commission adopted a European agenda on migration. It underlined the need for better management of migration by reducing the incentives for irregular migration, saving lives and securing the external borders. On 18 May 2015, the European Council agreed to establish an EU military operation, EUNAVFOR Med, to break the business model of smugglers and traffickers of people in the Mediterranean (EU Commission 2016).

The EUNAVFOR MED operation (later named as Sophia) has the authority by the UN Security council Resolution 2240 to operate in the High Seas and to take measures against the smuggling of migrants and human trafficking from the territory of Libya and off its coast (EU Commission 2016).

Bibliography

Amnesty International. A Safer Sea: The Impact of Increased Search And Rescue Operations In The Central Mediterranean. Amnesty International, 2015.

Blomfield, Christal, and Morehouse Michael. Irregular Migration in Europe. 2011. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/TCMirregularmigration.pdf .

Brian, Tara, and Frank Laczko. “Introduction: Migrant deaths around the world in 2015.” In Fatal Journeys Volume 2: Identification and tracing of dead and missing migrants. IOM, 2016.

Death by Rescue. The Forensic Architecture agency at Goldsmiths (University of London). 2016. https://deathbyrescue.org/report/narrative/.

European Commission. Eu Operations in the Mediterranean Sea. October 4, 2016b. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/securing-eu-borders/fact-sheets/docs/20161006/eu_operations_in_the_mediterranean_sea_en.pdf (accessed December 24, 2016).

—. Implementing the EU-Turkey Statement. June 15, 2016. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-16-1664_en.htm (accessed December 22, 2016).

—. Second Report on the Progress made in the Implementation of the EU-Turkey Statemen. June 15, 2016. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/proposal-implementation-package/docs/20160615/2nd_commission_report_on_progress_made_in_the_implementation_of_the_eu-turkey_agreement_en.pdf (accessed December 24, 2016).

Fargues, Philippe, and Sara Bonfanti. “When the best option is a leaky boat: why migrants risk their lives crossing the Mediterranean and what Europe is doing about it.” Migration Policy Centre (European University Insitute), October 2014.

Frontex. Annual Risk Analysis 2015. 2015. http://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Annual_Risk_Analysis_2015.pdf (accessed December 24, 2016).

—. Frontex Publishes Annual Risk Analysis 2014. May 15, 2014. http://frontex.europa.eu/news/frontex-publishes-annual-risk-analysis-2014-wc71Jn (accessed December 24, 2016).

—. JO Triton 2015: Tactical Focused Assessment. Janaury 14, 2015b. https://deathbyrescue.org/assets/annexes/7.Frontex_Triton%202015%20Tactical%20Focused%20Assessment_14.01.2015.pdf (accessed December 24, 2016).

Grant, Stefanie. “Recording and Identifying European Frontier Deaths.” European Journal of Migration and Law, 2011: 135–156.

Guiraudon, Virginie, and Christian Joppke. Controlling a New Migration World. London: Routledge, 2001.

Haas, Hein de. Borders beyond control? Janaury 7, 2015a. http://heindehaas.blogspot.ch/search?updated-min=2015-01-01T00:00:00Z&updated-max=2016-01-01T00:00:00Z&max-results=8 (accessed December 2016, 22).

—. Don’t blame the smugglers: the real migration industry. September 23, 2015b. http://heindehaas.blogspot.ch/search?updated-min=2015-01-01T00:00:00Z&updated-max=2016-01-01T00:00:00Z&max-results=8 (accessed December 22, 2016).

—. Smuggling is a reaction to border controls, not the cause of migration. October 5, 2013. http://heindehaas.blogspot.ch/2013/10/smuggling-is-reaction-to-border.html (accessed December 22, 2016).

Haas, Hein de, Katharina Natter, and Simona Vezzoli. “Growing Restrictiveness or Changing Selection? The Nature and Evolution of Migration Policies.” International Migration Review, 2016.

Hampshire, James. “Europe’s Migration Crisis,” Political Insight: Making Sense of Issues, Arguments, Trends and Development, December 2015.

IOM. Mediterranean Migrant Arrivals in 2016: 160,547; Deaths: 488. March 22, 2016b. https://www.iom.int/news/mediterranean-migrant-arrivals-2016-160547-deaths-488 (accessed December 24, 2016).

—. Mediterranean Migrant Arrivals Reach 358,156; Deaths at Sea: 4,901. December 20, 2016a. https://www.iom.int/news/mediterranean-migrant-arrivals-reach-358156-deaths-sea-4901 (accessed December 24, 2016).

—. “Dangerous Journeys”: International Migration Increasingly Unsafe in 2016. Issue brief. August 23, 2016. Accessed November 9, 2016c. https://missingmigrants.iom.int/“dangerous-journeys”-international-migration-increasingly-unsafe-2016.

—. “Key Migration Terms,” International Organization for Migration, January 14, 2015, http://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms.

—. “The Central Mediterranean route: Deadlier than ever” Accessed December 10, 2016 d. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/gmdac_data_briefing_series_issue3.pdf

—. “Migration Flows To Europe The Mediterranean Digest.” IOM, November 16, 2016f. http://migration.iom.int/docs/Med_Digest_2_17Nov16_.pdf.

Kassar, H, and P. Dourgnon. “The big crossing: illegal boat migrants in the Mediterranean.” Eur J Public Health (Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Public Health Association), 2014.

Katsiaficas, Caitlin. Asylum Seeker and Migrant Flows in the Mediterranean Adapt Rapidly to Changing Conditions. Migration Policy Institute. June 22, 2016. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/asylum-seeker-and-migrant-flows-mediterranean-adapt-changing-conditions (accessed December 22, 2016).

Last, Tamara, and Thomas Spijkerboer. “Tracking Deaths in the Mediterranean.” In Fatal Journeys. Tracking Lives Lost During Migration, edited by Tara Brian and Frank Laczko, 85-106. Geneva: International Organization for Migration, 2014.

Last, Tamara, Thomas Spijkerboer, and Orçun Ulusoy. “Deaths at the Borders: Evidence from the Southern External.” HIJRA – La Revue Marocaine de Droit d’Asile et Migration, 2016.

Monzini, Paola. “Sea-Border Crossings: The Organization of Irregular Migration to Italy.” Mediterranean Politics 12, no. 2 (July 1, 2007): 163–84. doi:10.1080/13629390701388679.

Spijkerboer, Thomas . “The Human Costs of Border Control.” European JournalofMigration andLaw, 2007: 127-139.

Triandafyllidou, Anna. “Irregular Migration in Europe in the Early 21st Century.” In Irregular Migration in Europe: Myths and Realities. Routledge, 2016 (2-4).

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). “Mixed Migration,” UNHCR, accessed November 6, 2016, http://www.unhcr.org/mixed-migration.html.

Vallet, Élisabeth. Borders, fences and walls: state of insecurity? Farnham, Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2014.

Watson, Scott D. The securitization of Humanitarian Migration: Digging Moats and Sinking Boats. London: Routledge, 2009.

Tables and Figures

Table (1)

IOM Mediterranean Update 13/12/2016

Table (2)

IOM Mediterranean Update 20/12/2016

| Arrivals by sea to Italy – Main Countries of Origin January – November 2016/2015 Comparison (Source: Italian Ministry of Interior) |

||

| Main Countries of Origin | 2016 | 2015 |

| Nigeria | 36,352 | 20,171 |

| Eritrea | 20,176 | 37,882 |

| Guinea | 12,534 | 2,045 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 11,556 | 3,175 |

| Gambia | 11,384 | 6,979 |

| Senegal | 9,643 | 5,212 |

| Mali | 9,416 | 5,307 |

| Sudan | 9,254 | 8,766 |

| Bangladesh | 7,578 | 5,039 |

| Somalia | 7,138 | 11,242 |

| Total, All Countries of Origin | 173,008 | 144,205 |

Figure (1): IOM Mediterranean Update 2015

Table (3)

IOM Missing Migrants Project: Mediterranean Sea

Figure (2): Migrant Report (2015)

Written by: Mona Saleh

Written at: The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Written for: International Migration and the Politics of Immigration – Melanie Kolbe

Date written: December 2016

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Cash for Migration Control: The EU-Egypt Strategic and Comprehensive Partnership

- Humanitarianism and Securitisation: Contradictions in State Responses to Migration

- Visceralities of the Border: Contemporary Border Regimes in a Globalised World

- Human vs. Feminist Security Approaches to Human Trafficking in the Mediterranean

- Migration in the European Union: Mirroring American and Australian Policies

- The Construction and Implementation of Migration Practices in Europe and America