Optimism in Brussels was misguided. The thaw in the European Union’s relationship with Belarus has stumbled, leaving EU officials scratching their heads about what to do. The debate quickly and predictably separated into two hidebound camps. One side argues for continued engagement with the autocratic regime of Aleksandr Lukashenko, while the other calls for a return to isolation. The problem for the EU is that its end goal in Belarus has become vague. I argue here that clarity about the end goal is critical for framing EU strategy towards the country. The policy alternatives being debated reflect the prioritising of different goals and make for an incoherent strategy. Moreover, policy incoherence creates wiggle room that Europe’s ‘last dictator’ deftly exploits.

It is the right moment to rethink EU strategy. After three years of ostensible rapprochement between the EU and Belarus, popular street protests in the spring pushed Belarus into the limelight. The Belarusian authorities tacitly allowed the protests for a while, even authorising some marches, but arrests of protest leaders and journalists followed (UN Human Rights Council 2017). Repression of a Freedom Day rally on 25 March captured news desk attention round the world. The EU’s reproach was low key. EU figures appeared reluctant to undo progress between the two sides, perhaps encouraged by the fact that Belarus’s relations with Russia, its traditional ally, remained strained. It was hoped that without Russia’s staunch support Belarus would need to heed EU criticism. Little more than a week later the presidents of Belarus and Russia met in St. Petersburg. Although bombings elsewhere in the city overshadowed their meeting, they announced that differences about oil supply and gas prices were settled and essentially restored the status quo ante (Hansbury 2017a). On 11 April Lukashenko relented in his criticism of the Russia-led Eurasian Union and signed the project’s Customs Code (TASS 2017).

The Shift in EU Strategy

If strategy is understood as connecting means to ends, then the goal of EU strategy has long been the democratisation of Belarus. The liberal belief that democratisation will reinforce regional security underpins this goal. Moreover, for a while the EU had a coherent strategy, with the means employed operating at two levels: a policy of engagement with civil society in the hope that this would bring about change from below, coupled with isolation of the leadership through a policy of sanctions. It is no coincidence that sanctions against Belarus were introduced in 2004, the same year as the EU’s ‘big bang’ enlargement into Eastern Europe. EU officials thought that Belarus could be persuaded to make the changes that could eventually lead to its participation in the European Neighbourhood Policy.

The EU’s strategy persisted with the Eastern Partnership, inaugurated in 2009 during a previous thaw in EU-Belarus relations. Although the project sought more overtly to include Belarus, and senior EU officials visited Minsk during its formative stage, the EU’s end goal was unchanged. For this reason, the Belarusian authorities’ conduct of the 2010 presidential elections and subsequent crackdown on protesters hampered engagement (Council of the European Union 2011). The EU commendably stepped back from functional cooperation; any strategy must remain constant and unaffected by the ambitions of the latest policy instrument. The EU had a coherent strategy. Only it failed. Belarus today is no closer to democratisation than it was in the late 1990s when Lukashenko consolidated his rule.

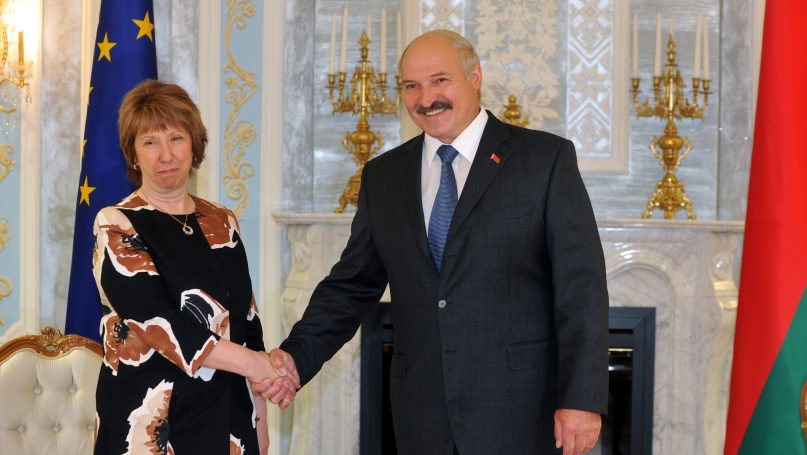

The removal of most EU sanctions in February 2016 marked a prospective sea change, accompanied by generous remarks about Belarus’s ‘proactive participation in the Eastern Partnership’ (Council of the European Union 2016) [1]. The EU was already referring to its policy as ‘critical engagement’ (EU External Action Service 2014, 2016) [2]. The 2016 change was welcomed by officials in Belarus, although frankly they had done nothing significant enough to warrant renewed attention. The selection of two non-loyalists to parliament in September 2016 signalled an intention on Belarus’s part to continue engagement; it did not signal any willingness to embrace democracy. Critical engagement thus provided official Minsk with a disproportionate reward for the release of political prisoners.

The Problem of EU Strategy

Indeed, if the EU still carries the torch for democratisation, there are reasons to think that critical engagement with the incumbent authorities will prove counter-productive. It is necessary to consider the goals of Belarus’s foreign policy to see why this is so. Belarus is militarily and politically aligned to Russia. As I have argued elsewhere, the incumbent regime seeks political ‘shelter’ in its formal alliance with Russia (Hansbury 2017b). Consistent with this, it adopts what it ambitiously describes as a ‘multi-vector foreign policy.’ In truth, this is nothing more than a hedging strategy, which is to say Belarus puts smaller bets on alternative outcomes to limit prospective losses. As a scholar of South East Asia explains, ‘hedging is a set of strategies aimed at avoiding … a situation in which states cannot decide upon more straightforward alternatives such as balancing, bandwagoning, or neutrality. Instead they cultivate a middle position that forestalls having to choose one side [outright]’ (Goh 2007).

Bearing these points in mind, critical engagement makes for an incoherent strategy. First, it serves the ends of the Belarusian leadership better than the EU; official Minsk receives the level of engagement its policy needs from the EU, while at the same time the EU withdraws the incentive to Belarus’s leaders to make concessions on issues such as human rights, the rule of law, press freedoms, and democracy. Lukashenko is able to tinker with minor changes to suit requirements and so that there will always be something for the EU both to praise and to criticise. Put simply, it creates flexibility for Belarus. Second, the strategy risks unintentionally alienating many of the Belarusian domestic interest groups that the EU has previously supported. Prospects for civil society diminish without support for these groups.

The Case for Isolation

The EU needs to be clear about its end goal. If democratisation is the goal, then a new mode of isolation must be found. There is no realistic option but limiting contact with Belarus’s leaders to the bare minimum. This does not imply a return to punitive sanctions, whose failure should be acknowledged, and reverting to the previous strategy would be unhelpful. Moreover, this means neither abstaining from criticism of Belarus’s record on issues of concern, nor does it imply an either/or choice between the EU and Russia. Although autocrats rarely democratise, it should be underscored that from the EU-perspective a democratic Belarus is free to ally to Russia or consent to fall inside a Russian sphere of influence (Hansbury 2017c) [3]. Positive sanctions (rewards) should remain on the table, but used only in the case of incontrovertible progress towards democratic values.

The advantage of isolation is that official Belarus will be forced to decide for itself whether it needs to engage with the EU and the prospective terms for engagement will be clear. Lukashenko’s goal is simple, to stay in power, and excessive dependence on Russia emasculates his power in the international arena. From the perspective of democratisation, Belarus’s formal participation in the Eastern Partnership serves no purpose and should be stopped. The risk of isolation is geopolitical and concerns the projection of Russian power deeper into Europe. However, Lukashenko jealously guards state sovereignty and, while the possibility of Russian moves against Belarusian sovereignty cannot be fully ruled out, the maintenance of EU resolve on Russia’s annexation of Crimea is likely to deter any flagrant aggression against Belarus. It is, though, possible that increased dependence on Russia would call into question the viability of the Belarusian state. For this reason, an engagement policy should not be rejected out of hand.

The Case for Engagement ‘Without Adjectives’ [4]

If the goal is an independent and viable Belarus, then a new mode of engagement is needed. While the wide-eyed may see any recent convergence of values as a reflection of change in Belarus, it is more plausible to argue that the greater movement is from the EU-side. The logic here is that the EU’s changed strategy reflected an apprehension of geopolitical processes. Backing down on the goal of democratisation would draw stern criticism, but – in view of the low level of engagement between the two sides – the goals of democratisation and support for independence and associated state-building cannot be pursued simultaneously. If the EU is unwilling to isolate the Belarusian authorities because of geopolitical insecurities, then it must engage properly with Lukashenko’s Belarus and provide support for state-building in spite of Lukashenko, however unpalatable and unpopular that will be.

Appropriate criticism would continue, as it does in EU-Azerbaijan relations, and the use of force to disperse crowds censured. Diplomatic engagement is necessarily pragmatic and selective, and it should always be critical. Under a new strategy, engagement would need to proceed on the understanding that there are few common values, although there are shared interests, especially in matters of border controls and energy security. Engagement means de facto legitimising the Belarusian parliament, which was excluded from Euronest (the Eastern Partnership’s parliamentary assembly) following violations during the 2010 parliamentary elections. Although the history of the Belarusian parliament need not concern us here, the reality is that after twenty years no viable alternative exists to Lukashenko’s puppet one [5].

Engagement with the authorities is not meant to imply neglect of traditional civil society partners, although for engagement to work would mean offering Belarusian officials more extensive participation in the Eastern Partnership. To build trust it would need member states from Western Europe and Scandinavia to take a leading role alongside Lithuania and Poland, of whom Belarus’s leaders harbour suspicions. Finally, it would recognise that Belarus has no ambitions to accede to the EU at present and that its retention of the death penalty will keep it outside the Council of Europe. The benefits and cooperation that might be offered to potential EU member states should remain unavailable to Belarus.

A Question of Security

The EU’s strategy towards Belarus became incoherent after the lifting of most sanctions. A decision needs to be taken about whether to prioritise support for democratisation or support for state-building; under Lukashenko there are limited opportunities to pursue the two ends together because they require different means. Either the EU isolates Lukashenko and his cohort, which realistically also means excluding Belarus from the Eastern Partnership, or it reluctantly but committedly engages with an autocratic regime. The former may rattle Lukashenko, especially if engagement with civil society continues, while the latter would unsettle both the domestic opposition as well as EU-based human rights campaigners [6]. Ultimately the choice is between a liberal commitment to security through democratisation, and a narrower understanding of security based on the existence of a functioning Belarusian state. The choice is not an easy one, but burking it will achieve nothing for the EU and provide Belarus leverage for its own ends.

Notes

[1] The exceptions were a ban on arms trade and the retention of measures against four individuals. These sanctions were further extended earlier this year (Council of the European Union 2017).

[2] Some detail is necessary here. ‘Critical engagement’ was the standard policy description for several years prior to 2016. Functional, sectoral cooperation increased between 2013 and 2016, although the removal of sanctions reflects the most significant weakening of the ‘critical’ part yet (European Commission 2013a, 2013b).

[3] In other words, the aspiration here is that isolation may change the president’s mindset. This sits awkwardly with my subsequent point about Lukashenko’s guiding goal being to retain power. However, Bueno de Mesquita and Smith (2011) cite Jerry Rawlings in Ghana as a rare case of an autocrat who democratised (p.218ff.). The avoidance of negative sanctions distinguishes the policy from previous policy.

[4] There has been a proliferation of adjectives to qualify engagement with Belarus. In the past the United States pursued ‘selective engagement’ (Jarabik 2006), while more recently a Belarusian analyst called for ‘smart engagement,’ although he neglected to specify what smart engagement looks like (Preiherman 2017). I suggest that the term ‘critical’ adds little as a policy description.

[5] The Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic, a government-in-exile since 1918, hardly fulfils this role.

[6] Engagement with civil society remains a moot point. There is ample evidence of penetration of civil society by the security services (e.g. Rudnik 2017).

References

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, and Smith, Alastair (2011), The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior is Almost Always Good Politics (New York)

Council of the European Union (2011), ‘Press release, 3065th Council Meeting, Brussels, 31 January 2011,’ pp.10-11

Council of the European Union (2016), ‘Belarus sanctions: EU delists 170 people, 3 companies; prolongs arms embargo,’ press releases

Council of the European Union (2017), ‘EU prolongs arms embargo and sanctions against four individuals for one year,’ press releases

European Commission (2013a), ‘Memo: ENP Package – Belarus’

European Commission (2013b), ‘New European Union support on health and development for Belarusian people,’ press releases

European Parliament (2017), ‘European Parliament resolution on the situation in Belarus’

European Union External Action Service (2014), ‘EU-Belarus Relations: Fact sheet’

European Union External Action Service (2016), ‘EU-Belarus Relations: Fact sheet’

Goh, Evelyn (2007), ‘Southeast Asian Perspectives on the China Challenge,’ The Journal of Strategic Studies, 30:4-5, pp.809-832

Hansbury, Paul (2016), ‘Money Talks: Belarus’s Quest for Cash in the West,’ Belarus Digest

Hansbury, Paul (2017a), ‘Bringing Belarus back into line?’ New Eastern Europe

Hansbury, Paul (2017b), ‘Friends in need: Belarusian alliance commitments to Russia in the wake of the Ukraine war,’ manuscript under peer review

Hansbury, Paul (2017c), ‘A Return to Spheres of Influence?’ Minsk Dialogue

Jarabik, Balazs (2006), ‘International Democracy Assistance to Belarus: An Effective Tool,’ in Joerg Forbrig, David R. Marples, and Pavol Demes (eds.), Prospects for Democracy in Belarus (Washington DC), pp.85-92

Preiherman, Yauheni (2017), ‘Why the EU Should Engage with Belarus,’ Carnegie Europe

Rudnik, Alesia (2017), ‘The Belarusian KGB: Recruiting from civil society,’ Belarus Digest

Tass (2017), ‘Belarus signs Eurasian Union’s Customs Code’

United Nations Human Rights Council (2017), ‘Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus’

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – What the European Union Can Do for Belarus

- Opinion – The European Union’s Status in the Russia-Ukraine Crisis

- Opinion – The Coming of Age of the European Union’s Indo-Pacific Strategy

- The European Union’s Digital Strategy and COVID-19

- Opinion – Macron’s Pivot Towards Russia

- Opinion – The NATO Madrid Summit and the Alliance’s New Dawn