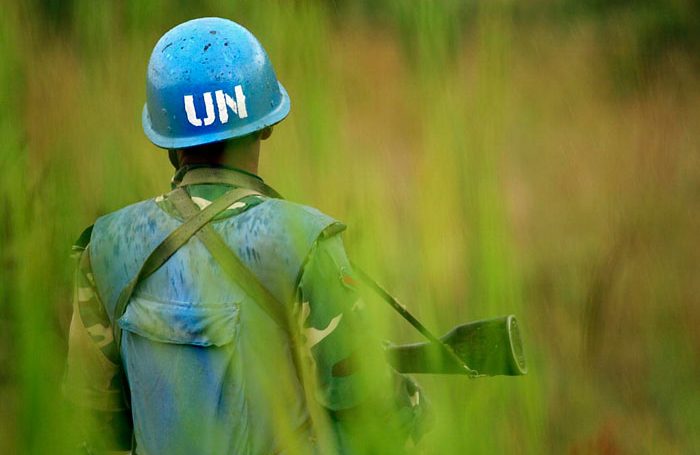

Media coverage of the United Nations is most often negative: deadlock in the Security Council over what to do in Syria and North Korea; the election of Saudi Arabia to the UN women’s rights commission; and – all too frequently in recent years – the sexualized violence and abuses committed by UN peacekeepers against the people they are supposed to protect. The issue of sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by UN peacekeepers is troubling not only because of the harms committed against vulnerable women, men and children in peacekeeping host countries, but also because these offenses keep happening in mission after mission, despite over a decade of efforts within the UN system to establish and enforce a zero-tolerance policy against SEA. Feminist scholars have incisively identified many intersectional, critical, and multi-faceted explanations for the persistence of SEA offenses, but a common factor underpinning them is the actuality of impunity: the likelihood that wrongdoing in a peacekeeping setting, up to and including criminal offenses, will go unpunished (impunity is also a focus of campaigns to end conflict-related sexual violence writ large, not just that committed by peacekeepers). Impunity in turn is both a result, and a perversion, of the immunity that UN peacekeepers are granted while in UN service. But while immunity has obvious ramifications for the potential aftermath of crimes committed by peacekeepers, it also complicates attempts to prevent these crimes in the first place, because crime prevention is at least partly predicated on the notion that undesirable actions can by pre-empted by the credible threat of specific sanctions. If the perception – and in the majority of cases, the reality – is that harmful or criminal actions do not have meaningful consequences for the perpetrators, can the UN prevent crimes permitted by peacekeepers?

Immunity and Peacekeeping

First, it is important to clarify how immunity works in a peacekeeping setting. Peacekeeping missions are made up of different categories of peacekeepers: military (where a further distinction is made between contingent military peacekeepers deployed as a cohesive group, usually in battalions; military staff officers; and military observers), police, and international civilian. This division of labor, in turn, entails different kinds of immunity and, relatedly, different jurisdictions and processes for investigating and punishing peacekeeper wrongdoing.

The simplest formulation is that UN international civilian peacekeepers, UN civilian police, military observers, and locally recruited, salaried staff enjoy functional immunity while on mission (the status of paramilitary formed police units, or FPUs, is less clear, although a UN group of legal experts includes FPUs in the same category as UN civilian police). Importantly, functional immunity is, as the name implies, not full or absolute: it protects peacekeepers from legal process for acts they perform in their official capacity, but should not apply for acts undertaken outside of their official function. For example, if a peacekeeper strikes and kills a pedestrian while on duty (driving to a meeting, conducting a patrol), they would be immune from prosecution; but if they strike and kill a pedestrian while driving home drunk from a nightclub or party, they should not be. Furthermore, peacekeepers’ immunity can be waived by the Secretary-General where it is deemed that the immunity protection perverts the course of justice, and where waiving immunity will not prejudice the interests of the UN. Thus far, this limitation on immunity has been more theoretical than actual. Waiving immunity in a peacekeeping context primarily means that the host state will be able to investigate, prosecute, and eventually punish the peacekeeper concerned, but it could also entail some form of shared jurisdiction with the peacekeeper’s home country.

In reality, the distinction between functional and full immunity for peacekeepers is overstated. Missions have operated with a generous interpretation of what counts as “official duties” in a peacekeeping context. There is also little precedent for waiving immunity, owing to qualms about the integrity, legitimacy, and functioning of host states’ judicial and corrective systems: because protecting the rights and security of UN peacekeepers is a foremost concern of the institution, waiving peacekeeper immunity where there are doubts about the kind of treatment they face will prejudice the interests of the UN. Finally, while peacekeepers face the theoretical possibility of prosecution in their home countries for crimes committed in peacekeeping sites, this is exceedingly rare. Not all states have legislation establishing jurisdiction over criminal acts committed by their citizens while abroad. Practical considerations related to different standards for the conduct of investigations, access to victims and witnesses, translation issues, and the storing and preservation of evidence, combined with resource limitations, also complicate home state prosecutions. The limited protections offered by functional immunity are thereby significantly broader in practice than in principle. For peacekeepers found or suspected to have committed a crime in-mission, the main punishment is administrative: they are suspended, investigated by internal oversight units, and potentially repatriated, demoted, or fired. Criminal sanctions, however, are seldom levied. While activists such as the Code Blue Campaign advocate for an independent special courts mechanism to deal with sexual violence by UN peacekeepers now covered by functional immunity, this idea has yet to gain traction among the majority of member states.

The protections afforded to military peacekeepers contributed by national governments (contingent military peacekeepers) – who make up the overwhelming majority of UN peacekeepers – are also broad, but differently constituted. According to the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) agreed between a troop-contributing country (TCC) and the UN, only TCCs can prosecute its military member for crimes committed on mission, usually in the TCC’s military justice system. These peacekeepers are thus never subject to the host state’s jurisdiction, even for serious crimes.

The extent to which TCCs take seriously their obligation to hold their soldiers accountable varies: some TCCs are active about investigating, repatriating, trying, and punishing their soldiers, while others effectively turn a blind eye. Recognizing these varying practices, the UN has taken measures to impose accountability on TCCs, including “naming and shaming” of countries that do not adequately follow up on SEA allegations. Going further, UN Security Council Resolution 2272 (2016) empowers the Secretary-General to repatriate military and formed police units “when there is credible evidence of widespread or systemic sexual exploitation and abuse by that unit (para. 1)”, and requests the Secretary-General to repatriate all military or formed police units of TCCs that systematically fail their accountability obligations, from the country where the allegations have arisen (para. 2). This does not, however, mean that the Secretary-General waives immunity in these cases, either for civilian or military peacekeepers. Indeed, even should the Secretary-General exercise his authority to repatriate units, the peacekeepers concerned are still subject only to their home country’s authority, not to the host country.

As Jeni Whalan notes, Resolution 2272 is simultaneously significant and flawed. While it represents an important step forward in facilitating accountability for SEA offenses, it is also constrained by the facts that the repatriation practices it requests are likely infeasible, and because the resolution “largely accepts the existing political and legal constraints that compromise peacekeepers’ accountability. To that extent, the resolution falls well short of the transformative changes sought by many advocates of stronger justice for victims (Whalan 2017: 3)”, such as the aforementioned special courts mechanism.

The Immunity-Impunity-Prevention Link

Peacekeeper immunity is important because it dovetails with issues of impunity and prevention. Put simply, if immunity effectively becomes impunity, then an important aspect of prevention – namely the “stick” that discourages people from behaving in immoral, criminal, or otherwise prohibited ways – is essentially removed. Insofar as the prevention of crimes by UN peacekeepers (whether sexual offenses or otherwise) depends upon the levying of predictable and consistent sanctions, then the current system of functional immunity and MoUs – which necessarily involve a great deal of latitude in punishing wrongdoing – is a serious challenge. Thus far, however, member states have been unwilling to coalesce on tougher measures to levy accountability for crimes committed on UN missions.

However, prevention is not only about the prospect of punishment, nor are prosecution and incarceration the only “sticks” available to influence behavior. The UN’s standards and norms in crime prevention outline multiple crime prevention strategies, including promoting well-being and encouraging pro-social behavior through social, economic, health and educational measures (social development approach); changing the conditions in communities that influence victimization, offending and insecurity (community-based prevention); reducing the opportunities for crime and increasing the likelihood of apprehension, including through environmental design and victim assistance (situational crime prevention); and preventing recidivism through reintegration and assistance programs.

While the specifics of crime prevention on a community or national level cannot be neatly mapped onto a diverse, multinational, and (at least for the peacekeepers involved) transitory peacekeeping mission, many of the principles remain relevant. Improving the living conditions, social opportunities, and available extracurricular activities for peacekeepers – akin to the social development approach – is one possibility that is often floated (with varying success) to reduce SEA offenses, as are public information campaigns (increasing the likelihood of apprehension). Victim assistance has also moved significantly up the agenda in terms of SEA, featuring strongly in the High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO) report (2015), the Global Study on the Implementation of UN Resolution 1325 (2015), and Resolution 2272, and resulting in the appointment of Jane Connors as the first Victims’ Rights Advocate for the UN. Finally, even “softer” (non-carceral) punishment can potentially play an important role in prevention. Repatriation and dismissal is a black-mark on one’s career, even if it does not result in a legal process. If peacekeepers see that the more robust measures contained in Resolution 2272 are being enforced, their perception of effective impunity will be dented, in turn prompting many to act differently.

Thus, while the unwillingness or inability to levy criminal accountability on peacekeepers is undoubtedly unsatisfying to victims, people in the host community, and those invested in the success of UN peacekeeping, it does not have to be determinant of the UN’s ability to prevent future crimes by UN peacekeepers. Concerted, targeted pre-deployment and initiation training on SEA and other prohibited activities (including financial crime, corruption, and drunk driving) – combined with efforts to improve the living conditions of peacekeepers; increase the investigative capacity available in and to UN missions; place a stronger institutional focus on victim assistance and victims’ rights; and robustly enforce the administrative sanctions the UN has available, as well as apply continuous pressure on member states and TCCs to investigate and punish SEA offenses in their ranks – should assist in the UN’s efforts to prevent crimes by UN peacekeepers.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Sexual Abuse in UN Peacekeeping: The Problem of Viewing Women as a ‘Quick Fix’

- The UN’s Role in The Institutional Abuse of Children: Wronged or Wrongdoer?

- The Global South and UN Peace Operations

- Opinion – Attacks on UN Peacekeepers in Cyprus Threaten a Fragile Status Quo

- Russia’s Challenge to Liberal Peacekeeping

- Peace-in-difference: A Phenomenological Approach