October 2017 started in Catalonia with a self-determination referendum deemed illegal by the Spanish government. In order to prevent the vote, following orders from Madrid, the police fired rubber bullets at unarmed protesters and smashed through the glass at polling places. The images irrupted and quickly spread around the world eroding the Spanish government’s legitimacy. During the following days the Catalan streets were taken by pro-independence as well as (for first time in a long time) by pro-unionist forces. The most intensive month lived by Spain and Catalonia in decades ended with Carles Puigdemont, president of the Generalitat (Catalan government) declaring the independence of the new Republic and the immediate answer of Spanish President Mariano Rajoy who dissolved the regional government and announced regional elections for December 21st. At the time of writing, part of the former government remains in prison while Puigdemont has moved to Belgium. This article explores what happened and why, discusses the limits of the confrontation between democracy (pro-independence main argument) and legality (pro-unionist main argument), the role of the European Union and, finally, what can result from the December elections.

October 2017

On October 1st a referendum declared illegal by the Spanish Constitutional Court took place in Catalonia, a wealthy Autonomous Community with 7 500 000 inhabitants. The Spanish government led by Mariano Rajoy (the right-wing Popular Party) had announced several times that no referendum would take place. In order to avoid it, thousands of civil guards (Spanish National Police) were sent to the Autonomous Community to prevent the vote. The police captured boxes and paper ballots and closed polling places. But the grassroots movement and the support of hackers (providing with a system to organize ‘universal suffrage’, allowed voters to move to the next one when their polling place was close) helped to organise the vote. The day ended with scenes of violence against peaceful old and young people spreading all around the world. Within the European Union, civil society wondered how can the peaceful will for self-determination be repressed with violence in a consolidated democracy. At least 893 people and 33 police officers were reported to have been injured. The EU representatives remained silent and qualified the issue as an internal matter for Spain. Rajoy’s first reaction was to just deny the facts[1].

As a next step, the Catalan Parliament was expected to Declare Unilaterally the Independence (DUI). Then, the Spanish government announced the suspension of the Autonomous government by applying article 155 of the Constitution (a special article never activated before). On October 16th the presidents of the Catalan National Assembly (ANC), Jordi Sánchez, Òmnium Cultural and Jordi Cuixart –the main grassroots organizations backing the claim for independence– were sent to jail pending a sedition trial at the Spanish National Court. Sánchez and Cuixart were accused of leading protests to obstruct police operations against the October 1st referendum and could face up to 15 years in prison.

The last week of the month Carles Puidemont received opposed pressures to either declare independence (from the radical side of the pro-independence movement) or to call for new elections (from a more moderate faction within his party, the PDeCAT). Nerves and anxiety were in the air and in social media. The moderate faction of his party worried because the biggest banks and companies were moving their registered headquarters to other parts of Spain while they were aware of their failure in wining international support and particularly European support (no surveys are available but it could be the case that it expresses a new divide between representatives and the represented, with a common opinion if not in favour of independence, at least in favour of letting the Catalans to vote).

After an intensive week in which everything seemed possible, on Friday 27th Puidgemont did declare the independence. The day after, he and his cabinet were formally removed from their posts, and their powers and responsibilities were taken over by the central government (based on article 155 of the Constitution). President Rajoy announced Catalan elections for December 21st, 2017. Puigdemont and 13 members of his former cabinet had to testify before the Audiencia National as part of the investigation into allegations of ‘sedition, rebellion and misuse of public funds’ (facing until 30 years of prison). But Puigdemont and five of his councilors unexpectedly moved to Belgium. Few days after, nine members of the former government showed up to the Audiencia National for a hearing and left the building to get imprisoned in Madrid.

How Did the Conflict Scale Up to This Level?

Almost two years before the 2017 referendum, the Catalan pro-independence parties grouped in Together for Yes (Junts pel si)[2] had won the election of 27 September 2015, obtaining 62 seats. It has been defined as “plebiscitarian” by the pro-independence parties. However, the alliance failed to gain an absolute majority and then arrived at an agreement with the radical left-wing grassroots and pro-independence Popular Unity Candidacy (Candidatura d’Unitat Popular, CUP), which had 10 seats. Altogether it came to 72 seats out of a total of 135, leaving room to start the process of “disconnection” (desconnexió) from Spain promised by these parties during the electoral campaign. However, the absolute majority did not reflect a majority of the votes cast (ended up just under 48 per cent). Notice also that even if currently the pro-unionists are asking everybody to go to the polls in December suggesting that abstention played a role in 2015, the turnout in 2015 was 77 per cent, the highest in Catalan elections since Spain’s transition to democracy in the 1970s.

On November 9th, 2015, the parties presented the Declaration of the Initiation of the Process of Independence of Catalonia. All the other groups voted against the declaration: Citizens (Ciutadans, Cs), the Catalan Socialist Party (Partit Socialista de Catalunya, PSC), the Catalan People’s Party (Partit Popular de Catalunya, PPC) and the alternative-left coalition Catalunya Sí que es Pot.

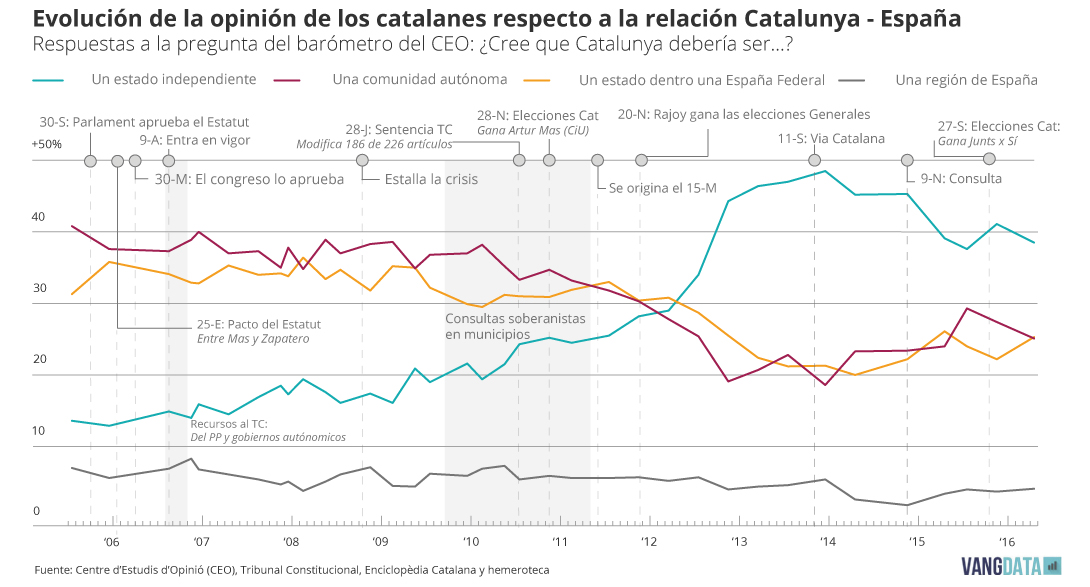

However, the movement had started earlier. Catalan nationalism is not ethnic. Even if the Catalan language, historical institutions and the Francoist legacy are usually part of the explanation in support to the will for an independent state, the social support for independence remained below the 20 per cent during the transition and until the early 2000s[3] as can be seen in the graph.

The reasons behind the growing support for independence can be traced to recent history. On September 30, 2005, the Catalan Parliament approved the New Statute with 120 votes (all the parties represented—CiU, the PSC, the ERC and ICV-EUiA—excluding the Popular Party which had 11 votes). The text was submitted to the Spanish Parliament, where the deputies introduced several changes. Once approved in Madrid, the amended Statute was ratified by the Catalan Parliament (with less support than the original version, given that this time not only the PPC but also ERC voted against it, making a total of 28 percent of the parliament against. Finally, the text was submitted to referendum on June 18th, 2006. With a low turnout (48.9 percent), the ‘Yes’ option received 73 percent of the votes and the ‘No’, 20 percent. On June 28th, 2010, the Constitutional Tribunal ruled against the Statute, cutting most of its crucial articles. A few days later the grassroots movement jumped into the public Catalan scene in a trend which has not stopped until now. On July 10th the Catalan civil-society organization, Xarxa Òmnium organized a demonstration under the slogan “We are a nation, we decide”. Since then, hundreds of municipalities have organised informal referendums mostly backed by mayors while each national day (the diada, celebrated on September 11) was a new opportunity to show the growing massive force of the pro-independence movement.

Since 2012, the idea of holding a referendum has had a central place in Catalonia, with some parties in favour (within this group there is also a division between the unilateral or negotiated options) and some parties against. The first attempt at organising it was legally blocked and ended in a non-binding informal consultation on November 9th, 2014.

Legality vs Democracy?

The arguments against holding a referendum are based on the violation of the Constitution. This has been and still is the main reason alleged by the Spanish government for prohibiting a vote. For the pro-independence movement, the right to decide should not be necessarily based on the ‘remedy’ theory (i.e. a nation having the right to become a state because of the grievances suffered in hands of a parent state[4]) but on the will of the people, or in other words – on a democratic idea. The focus seems then to be on the opposition between the law and the will of the people. However, the argument is contradicted by recent events.

Many constitutional lawyers in Spain have reacted against the action of the National Audience. The charges of ‘sedition’ and ‘rebellion’ were brought in relation to a vote during which no organised violence from the promoters has been proved to provoke such reactions. The Catalan government is accused of implementing a ‘secret conspiracy’ when actually all of its actions were in furtherance of its program for the elections of 2015.

Nevertheless, the argument of the ‘will of the people’ put forward by the pro-independence movement is also contradicted by facts. Even if what happened on October 1 can undoubtedly be considered a massive demonstration, this cannot assume a mandate towards independence. The violence registered, the many problems faced by the organisers to guarantee a vote, the absence of the ‘No’ supporters from the Campaign, the lack of international observation and even the lack of a neutral body in charge of counting the votes do not play in favour of the argument. Even if the support proves to be high, it is unclear to what extent it is majoritarian.

EU Pragmatism Will Not Work

For a long time the position of the European Union has been crucial in the debate in favour/against independence in Catalonia. Pro-independence parties have always claimed that Catalonia is part of the EU and in case of independence it should remain or should quickly become a new member. From the unionist side it is argued that independence would indubitably move the new state outside the EU with severe economic and social consequences. Despite the intensive efforts by the Catalan government, it failed in gaining EU (as well as international) support. The authorities of the European Commission and the EU have once more backed the Spanish government, although issuing a warning in relation to its use of force on October 1st.

However, the presence of Puigdemont and some former members of his government in Belgium could have been a master movement to internationalise the conflict. Now the Belgian Court has to decide whether to accept the request for extradition, but in doing so it needs to first analyse if the charges are compatible with the country’s legislation.

The last events had a minor but relevant effect in opening room to many politicians discontented with the Spanish action. A few Swiss and Belgian politicians have already spoken against the prosecution of politicians and the necessity for negotiating (a fair referendum?).

What’s Next? December 21

Will the Catalan elections be able to resolve the conflict? The first surveys published with data from the last week of October suggest that will not be the case. According to Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió (CEO), the support for ‘independence’ has grown and would win over the ‘remain’ option. Among respondents, 64 per cent feel that Catalonia has achieved an insufficient level of autonomy. The question “Do you want Catalonia to become an independent State?” is answered with a ‘Yes’ by 48,7 per cent of the sample and rejected by 43,6 per cent.

As for political parties’ support, the week commencing November 9 the period to register parties and alliances ended. It is still unclear if pro-independence parties will run together. It is clear that the ones self-nominated as ‘constitutionalistas’ will attend the rally with their own candidates. The CEO survey suggests that the results could be quite similar to the ones obtained in September 2015. With some internal transfers within pro-independence (ERC with votes coming from CUP and PdCAT) and pro-union parties (Ciutadans growing with votes coming from PSC), the pro-independence parties would reach the majority.

With this data at hand and the overview of how the pro-independence movement has been growing since 2010, it seems that the elections will hardly change the scenario. There is a division in Catalan society, with two important majorities which cannot operate in isolation. Besides that, pro-independence or pro-union, more than 70 per cent of the Catalans want to vote. The Popular Party has neither showed any capacity to develop a discourse to attract the Catalans who have emotionally left Spain, nor has it shown ability to propose alternative politics of devolution. Would it finally open room for a political dialogue? It does not seem likely, but sooner or later someone should do it, no other option could restore lost legitimacy. Thus, it is about democracy.

Notes

[1] And once it happened, he kept neglecting the facts: “At this point, I can tell you very clearly: Today a self-determination referendum in Catalonia didn’t happen. We proved today that our state reacts with all its legal means against every provocation.”

[2] The pro-independence platform was the result of the electoral alliance among the centre-right Democratic Convergence of Catalonia (CDC) and the left-wing Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), the Democrats of Catalonia (DC) and the Left Movement (MES)

[3] For a more detailed description see “The right to decide? The Catalans dilemma”.

[4] Caspersen, Nina. 2011. Unrecognized States: The Struggle for Sovereignty in the Modern International System, Cambridge: Polity

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Spain’s Request For NATO Coronavirus Aid: Will Turkey Answer?

- COVID-19 and Democracy in the European Union

- Cuban Nationalism and the Spanish-American War

- Ceuta and Melilla: Pioneers of Post-Cold War Border Fortification

- The Days of May (Again): What Happens to Brexit Now?

- Exhuming Norms: Comparing Investigations of Forced Disappearances