This is an excerpt from The ‘Clash of Civilizations’ 25 Years On: A Multidisciplinary Appraisal. Download your free copy here.

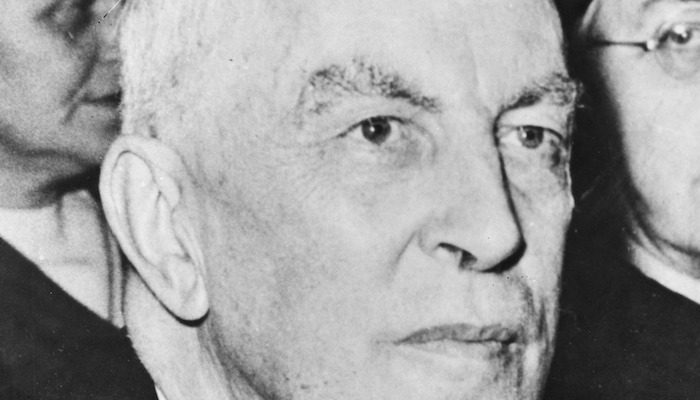

Exactly forty years before Foreign Affairs published Samuel P. Huntington’s original ‘The Clash of Civilizations’ article, in the northern summer of 1993, the British historian Arnold J. Toynbee was in the middle of a stormy debate about an equally controversial work of civilizational history and geopolitical prediction, The World and the West (Toynbee 1953). Three years away from retirement from his post at the Royal Institute of International Affairs (Chatham House), Toynbee was then 64 years old, and stood, as Huntington did in the early 1990s, at the pinnacle of his career, feted as modern sage for his sweeping grand historical studies and his acute analyses of international politics. His books were selling in the hundreds of thousands and his opinions on a wide range of topics avidly sought by the public (see McNeill 1989).[1] The appearance of The World and the West, however, marked the start of Toynbee’s fall from grace. Thereafter, his reputation began to decline, in part because the political views he expressed in that book – best thought of as left-liberal, internationalist, anti-colonial, and empathetic (though not sympathetic) towards Soviet Communism – were growing increasingly unfashionable, as Britain tried to reassert its grip on what remained of its empire and the Cold War-polarized political debate on both sides of the Atlantic (Hall 2012). In this context, Toynbee’s argument in The World and the West and other publications that the West was ‘the arch-aggressor of modern times’ was not at all well received (Toynbee 1953, 2).[2] In parallel, his standing as a scholar fell too, as the historical profession grew much less tolerant of civilizational history, as well as the kind of religiosity Toynbee increasingly professed.

Ironically, just as the idea of the ‘West’ became prominent in American and Western European political discourse, the concept of civilization was in the process of being set aside by academic historians as unhelpfully vague and imprecise (see Geyl 1956). By the time Huntington revived ‘civilization’ as a unit of historical and geopolitical analysis in 1993, Toynbee’s work had long been set aside as little more than a curiosity.[3] It is not surprising, therefore, that his ideas did not feature in Huntington’s original Foreign Affairs article, nor that they received relatively short shrift in the book-length version of The Clash of Civilizations (Huntington 1993; Huntington 1998). But there are good reasons, I argue in what follows, to revisit Toynbee when reading Huntington’s argument. His concept of civilization, developed in A Study of History (12 volumes, 1934–61), and especially his explorations of ‘encounters’ between civilizations and the effects he thought those encounters had, are useful instruments for destabilizing some of Huntington’s key claims.

Defining Civilizations

There are many differences between Huntington and Toynbee’s projects, especially in their conclusions and their policy prescriptions, but they had similar aims and assumptions. Both sought to use civilizational history to explain contemporary phenomena. Huntington’s aim was to try to provide a parsimonious explanation for what he perceived as new patterns of behavior by states (and some non-state actors) in post-Cold War international relations, patterns that he argued could not adequately be explained by existing state-centric theories (Huntington 1998, 19–39). In particular, he was interested in the agitation and civil conflict that had emerged towards the end of the 1980s in parts of the Muslim world, in the soon-to-be-dissolved Soviet Union and state of Yugoslavia, between Hindu nationalists and Muslims in India, and between Tibetans and Han Chinese (Huntington 1993). Toynbee too was interested in explaining the causes of conflict, but his objective was to explain why the West had so catastrophically descended into a devastating war in 1914 and why international disorder persisted after 1919. Struck at the outset of the First World War by the apparent parallels between what he knew of ancient Greek history, especially of the Peloponnesian War, and the present, he set out to ascertain whether other past civilizations had experienced similar episodes of conflict – ‘Times of Troubles’, as he called them – and to determine whether the episodes had similar causes (Toynbee 1956b, 8; see also Hall 2014).

Both Huntington and Toynbee determined that the best way to explain the causes of contemporary conflicts was to look at civilizations rather than at states or other kinds of political or social groups. Toynbee began to explore this possibility first in The Western Question in Greece and Turkey (1922), which tried to explain the ferocity of the Greco-Turkish war of 1919–22, with its grim episodes of what later became known as ethnic-cleansing,[4] but only set it out in full in the first volume of his Study of History (1934). His argument was that historians must take a civilizational view of the past, because the histories of lesser social bodies made little sense in isolation. Civilizations, on this view, were the necessary context within which historical events must be interpreted, rather than things like nation-states, which were modern inventions (Toynbee 1934, 44–50). Huntington’s account of a civilization was strikingly similar. In the book version of The Clash of Civilizations he defined a civilization as ‘the broadest cultural entity’ and argued that ‘none of their constituent units can be fully understood without reference to the encompassing civilization’ (Huntington 1998, 43 and 42). For both, only a civilizational view was sufficient to explain the phenomena they wanted to analyze.

Contacts and Clashes

Both Toynbee and Huntington acknowledged, of course, that these understandings of civilizations generated problems for the stories that they wanted to tell. Toynbee knew from the start that using a civilization to frame the interpretation of some historical episode might not, in fact, be sufficient. Civilizational boundaries (in so far as we can define them) are porous; civilizations interacted with others, and thus it might be necessary for historians to place things in an even wider context if they were to explain them properly. He had done this in the Western Question, a study of what happened when two civilizations came into contact ‘in space’, to use his language, but he had also long been concerned with contacts ‘in time’, where a civilization drew up inherited knowledge or beliefs from an earlier one.[5] In particular, as a classicist, Toynbee was interested in contacts between the ancient Greek or ‘Hellenic’ civilization, which he considered ‘dead’, and later civilizations, especially the transmission and mediation to the West of ideas and practices by the medieval Byzantine empire, but also the influence of the Hellenic ideas on both the Muslim and Hindu worlds.[6]

What Toynbee found in his Study of History, indeed, was that civilizations are rarely immune from outside influence, either from past civilizations or present ones. Only a couple of examples rose and fell in relative isolation, unaffected by others. Most emerged either out of a pre-existing civilization, drawing on its legacy of ideas and beliefs in a process Toynbee called, in his peculiar idiom, ‘Apparentation-and-Affiliation’(1934, 97–105). Thus the West and the Orthodox world drew on Hellenic civilization; what he called the Babylonian and Hittite civilizations drew on the Sumerian; the two branches of the modern Islamic world, Arabic (Sunni) and ‘Iranic’ (Shia), drew on the pre-Islamic ‘Syriac’ civilization; and what he took to be contemporary ‘Far Eastern’ civilization, in China, Korea, and Japan, drew on a pre-existing but distinct ‘Sinic’ civilization, and so on (Toynbee 1954b, 107).[7] Then there were encounters between ‘living’ civilizations that shaped those involved. Some led to ‘fruitful’ exchanges (Toynbee gave the examples of the influence of Hellenic thought and art on ancient India, and then later on both medieval Christianity and Islam, as well as the Renaissance); some to the near total collapse of civilizations (such as those in the Americas); and some to retrenchment and resistance (as occurred in parts of the ‘Far East’ and the Muslim world when they encountered the modern West) (Toynbee 1954b).

Huntington, for his part, also wrestled in The Clash of Civilizations with the issue of boundaries and inter-civilizational contacts. He conceded that:

Civilizations have no clear-cut boundaries and no precise beginnings and endings. People can and do redefine their identities and, as a result, the composition and shapes of civilizations change over time. The cultures of peoples interact and overlap.

He recognized too that civilizations ‘evolve’, observing that ‘[t]hey are dynamic, they rise and fall, they merge and divide’ (Huntington 1998, 44). But Huntington insisted that ‘[c]ivilizations are nonetheless meaningful entities, and while the lines between them are seldom sharp, they are real’ (Huntington 1998, 43). Moreover, he asserted that, historically, civilizations had rarely interacted, and there were few instances of inter-civilizational contact that led to really significant changes in the one or the other, until the modern era. Prior to 1500 CE, he argued, contacts between them were either ‘nonexistent or limited’ or ‘intermittent and intense’ (Huntington 1998, 48). Distance and transport technologies prevented anything more.

Only after 1500 CE, with the invention of new technologies that permitted more people to travel longer distances, Huntington maintained, did situations arise in which civilizations could be substantially changed by encounters with others. Importantly, however, he asserted that not all civilizations were changed to the same extent, and implied that some elements of a civilization – its cultural or religious kernel – could not be changed, though it could be destroyed. Instead, in the modern period, he argued ‘[i]ntermittent or limited multidirectional encounters among civilizations gave way to the sustained, overpowering, unidirectional impact of the West on all other civilizations’ (Huntington 1998, 50). The result was the ‘subordination of other societies to Western civilization’. This occurred not because of the superiority of Western ideas, Huntington insisted, but because of the superiority of Western technology, especially its military technology (Huntington 1998, 51). And despite their ‘subordination’ to Western power, he maintained, non-Western societies remained culturally distinct and resistant to Western cultural influence.

The technological unification of the world by the West thus brought into being, for Huntington, a ‘multicivilizational system’ characterized by ‘intense, sustained, and multidirectional interactions among all civilizations’ (Huntington 1998, 51). It had not, he went to great pains to argue, generated anything like a ‘universal civilization’.[8] No universal language is in the process of formation, he argued; rather, languages once marginalized by imperial powers are being revived. Nor are we seeing a universal religion emerge; instead, adherents of major religions are becoming more entrenched in their beliefs, some even more fundamentalist. In sum, modernization has taken place without Westernization, strengthening non-Western cultures insofar as they have acquired new technologies, including new weapons, and reducing ‘the relative power of the West’ (Huntington 1998, 78).

Technologies and Ideas

Toynbee was also deeply concerned by the impact of the West on the rest of the world – that was the central theme of his incendiary The World and the West. His work on Turkey, during the First World War and after, left him well versed in the dynamics of modernization in a non-Western society, under the Ottomans and then under Kemal Ataturk. In his Study of History he ranged much further, examining Peter the Great and then the Bolshevik attempts to modernize Russia, the Meiji Restoration in Japan, and Sun Yat-sen’s attempt to reform post-Qing China. He recognized that the spread of Western technologies to other societies was undercutting the relative power of the West, but he also emphasized that modern weapons and military science were not the only inventions that were aiding the revival of non-Western societies. Political and other ideas, including philosophical arguments and religious beliefs, Toynbee argued, had also changed those societies, and fueling what became known, in the 1950s, as the ‘Revolt against the West’ (Hall 2011).

Although during the course of writing A Study of History, Toynbee offered different accounts of what occurred when civilizations encountered each other, he was consistent in insisting that the effects were much more dramatic than Huntington suggested. Like Edward Gibbon, he argued that ‘major’ religions were the product of the intrusion of ‘foreign’ ideas into a civilization, as Christianity had arisen as Jewish millenarianism, appeared on the fringes of the Greco-Roman world, slowly infected its consciousness and – for the young Toynbee as for Gibbon – destroyed that classical world (Gibbon 2010). Later, as Toynbee shed his liberal rationalist agnosticism and became more sympathetic to religion, his view of the birth of Christianity and other major religions changed (see Toynbee 1956a), but he remained convinced that ideas transmitted by inter-civilizational encounters could bring about major social and political changes within civilizations. Like Huntington, he argued that encounters might lead to the transmission of just one technology or idea and not others, much less to an entire corpus of civilizational ideas and beliefs. In The World and the West, as we have seen, he detailed how modern technology had been transmitted to Russia, Turkey, and the ‘Far East’, while Western religious ideas, for example, had been rejected. Toynbee suggested we understand this process by way of a metaphor borrowed from physics. This was what happened, he argued, ‘when the culture-ray of a radioactive civilization hits a foreign body social’, as the latter’s ‘resistance diffracts the culture-ray into its component strands’ (Toynbee 1953, 67).

Toynbee rightly recognized, however, that modern military technology was not the only thing that had been transmitted to the non-West during the period of Western imperial expansion. He was particularly concerned with the transmission of political ideas, especially nationalism and the concept of the nation-state, ‘an exotic institution’, as he put it, ‘deliberately imported from the West…simply because the West’s political power had given the West’s political institutions an irrational yet irresistible prestige in non-Western eyes’ (Toynbee 1953, 71). A sound internationalist, Toynbee was deeply exercised by this spread of nationalism and the nation-state, an institution he thought both obsolete, given the economic unification of the world, and even more worryingly, prone to being set up as some kind of false idol for the masses to worship (Toynbee 1956a, 27–36).[9] But setting this normative spin aside, his core point – that inter-civilizational encounters spread more than technology and weapons – is surely irrefutable; indeed, the notion that the sovereign state, organized along national lines or not, was spread by Western imperial expansions is the consensus view in contemporary International Relations (see Bull and Watson 1984).

Toynbee was deeply troubled also by the spread of things like Western consumerism, which he thought, like Mohandas Gandhi, could even infect non-Western societies like India to their detriment (Toynbee 1953, 79–80). But at the same time, he outlined a more positive message, which also challenges key elements of Huntington’s thesis, and sits uneasily with other aspects of his own thinking. Although much of Toynbee’s Study of History was taken up by warnings against mimesis or the imitation of others, as well as pleas for authentic creative ‘responses’ to ‘challenges’,[10] he was also convinced that the technological and economic unification of the world by the West had fundamentally changed our – humanity’s – historical perspective.

This change generated a number of effects. First, Toynbee observed, it made it harder for certain societies to think of themselves as a ‘Chosen People’ and uniquely civilized (Toynbee 1948, 71–79). A few in the postwar West, he thought, still suffered from this delusion, but it would pass in time, as they realized that Western history was not as unique as they had been taught (Toynbee 1948, 79). Second, it was now possible to study the thought of others’ civilizations. Non-Westerners, he noted, were doing this in numbers, ‘taking Western lessons at first-hand in the universities of Paris or Cambridge and Oxford; at Columbia and at Chicago’, as was right and proper as the heirs to the riches of all past and contemporary civilizations. Some had ‘caught…the Western ideological disease of Nationalism’, Toynbee lamented, but at least their historical perspective was no longer ‘parochial’ (Toynbee 1948, 83). They, he observed, ‘have grasped the fact that…our past history has become a vital part of theirs [italics in original]’. What was needed was for Westerners to make a similar leap, recognizing that Africa’s or China’s past was also ‘theirs’, in the same way that they regard the histories of the ‘extinct civilizations’ of ‘Israel, Greece and Rome’ as theirs (Toynbee 1948, 89).

The unification of the world, Toynbee argued, meant that all histories belonged to all, and that meant the distinction between Western and non-Western was no longer tenable:

Our own descendants are not going to be just Western, like ourselves. They are going to be heirs of Confucius and Lao-Tse [sic] as well as Socrates, Plato, and Plotinus; heirs of Gautama Buddha as well as Deutero-Isaiah and Jesus Christ; heirs of Zarathustra and Muhammed as well as Elijah…; heirs of Shankara and Ramanuja as well as Clement and Origen;…and heirs…of Lenin and Gandhi and Sun Yat-sen as well as Cromwell and George Washington and Mazzini (Toynbee 1948, 90).

This was heady stuff, of course, and it led Toynbee off toward trying to come up with a plan for a syncretic religion, blending insights from existing ones, that might serve to overcome political conflict and serve as the basis for the future reconciliation of the world (see Toynbee 1956a; Toynbee 1954a). But his core point – that the philosophies and concepts of all civilizations, both ‘living’ and ‘extinct’, were now for the first time available for all to read, study, adopt, and adapt, accepting the challenges of translation – was a powerful one, especially in view of Huntington’s insistence that civilizations are divided along sharp lines, despite the economic and technological unification of the world.

Conclusion

The conclusion to the book version of The Clash of Civilizations opens, oddly enough, with a discussion of Toynbee’s warning of the ‘mirage of immortality’ he thought beguiled and distracted civilizations in decline (Toynbee 1945a, 301). But where Toynbee called for an effort to draw upon the inheritance bequeathed by all civilizations to construct new social and political institutions befitting of the ‘ecumenical community’ created by the West’s unification of the world (Toynbee 1954a), Huntington argued for something narrower . In The Clash of Civilizations and especially in Who are We? (2004), he called for the renewal and revival of the West, which he thought had been weakened by immigration and by multiculturalism, which aided and abetted the spread of non-Western cultural and religious beliefs and practices, by economic malaise, and by ‘moral decay’(1998, 304). The United States, he argued, must defend the Anglo-Saxon Protestant beliefs and practices that delivered past social and political success, so as to ensure it can play the necessary role of the West’s ‘core state’.

Toynbee, of course, warned against such policies, which he characterized as anachronistic archaisms. But more importantly, as we have seen, his Study of History raises questions about the assumptions that underlie Huntington’s prescriptions. In particular, Toynbee’s work suggests that historical encounters between civilizations were more frequent and consequential than Huntington allowed. Second, it points to the extent of the transmission not just of technologies, but also of social and political ideas, and to their impact, as bodies of thought like Jewish millenarianism encountered Hellenic philosophy to create Christianity, for example, or indeed how Christian ideas shaped Hindu revivalism.[11] Third, it draws attention to agency and away from Huntington’s overly structural account of ideas and beliefs, pointing to the role played by both scholars and political actors in borrowing, accepting, appropriating, and indeed manipulating ‘foreign’ philosophies and religious concepts, as well as technologies, for their own purposes, as Toynbee’s non-Western students did when they recognized, implicitly or not, Western history as ‘theirs’ as well as ‘ours’. In turn, of course, that draws attention to the great unanswered, pressing question of The Clash of Civilizations: who is responsible for this resurgence of cultural and religious politics in the post-Cold War era?

Notes

[1] On Toynbee’s moment of ‘Fame and Fortune’, see McNeill 1989, 205–234, Toynbee’s image even appeared on the cover of Time magazine, on 17 March 1947, with the title, referring to his prognostications about the West: ‘Our civilization is not inexorably doomed’.

[2] For one vehement rebuttal, see Jerrold 1954. For a more measured assessment, see Perry 1982.

[3] McNeill (1989, 243–258) traces this decline. Recently, there has been a mini-revival of Toynbee studies. See, for example, Hutton 2014 and Castellin 2015.

[4] For background, see Clogg 1986.

[5] The issue of contacts was the subject of Toynbee’s (1954) A Study of History, vol. VIII.

[6] For an early essay on this topic, see Toynbee 1923. In the essay, Toynbee wrote: ‘Ancient Greek society perished at least as long ago as the seventh century A. D.’, but that the West was its ‘child’ (289), the inheritor of a ‘legacy bequeathed’ (290). He recognized, however, that the Muslim and Hindu worlds were also heirs.

[7] Some of these supposed civilizations, such as the ‘Syriac’, ‘Sinic’, and ‘Far Eastern’ were (and remain) controversial.

[8] Huntington devoted an entire chapter of the book to the debunking of that suggestion (1998, 56–78).

[9] He also warned against the idolatrous worship of world-states, philosophers, religious institutions, and technology, among other things.

[10] See especially Toynbee, Study of History, vols. II and III. Creative responses to challenges, he posited, brought about ‘growth’ (that is, loosely, progress) in civilizations. He derived this theory from a number of sources, especially from the French philosopher Henri Bergson.

[11] On the impact of Christianity on, for instance, Swami Vivekananda’s Hindu revivalism, see Sharma 2013.

References

Bagby, Philip. 1959. Culture and History: Prolegomena to the Comparative Study of Civilizations. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bull, Hedley and Adam Watson, eds. 1984. The Expansion of International Society. Oxford: Clarendon.

Castellin, Luca G. 2015. “Arnold J. Toynbee’s Quest for a New World Order: A Survey.” The European Legacy 20(6): 619–635.

Clogg, Richard. 1986. Politics and the Academy: Arnold Toynbee and the Koraes Chair. London: Frank Cass.

Geyl, Pieter. 1956. “Toynbee’s System of Civilizations.” In Toynbee and History: Critical Essays and Reviews edited by M. F. Ashley Montagu. Boston: Porter Sargent, 39–76.

Gibbon, Edward. 2010. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vols. I–VI. London: Everyman’s.

Hall, Ian. 2011. “The Revolt against the West: Decolonization and its Repercussions in British International Thought, 1960–1985.” International History Review 33(1): 43–64.

Hall, Ian. 2014. “‘Time of Troubles’: Arnold J. Toynbee’s Twentieth Century.” International Affairs 90(1): 23–36.

Hall, Ian. 2012. “‘The Toynbee Convector’: The Rise and Fall of Arnold J. Toynbee’s Anti-Imperial Mission to the West.” The European Legacy 17(4): 459–466.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1993. “The Clash of Civilizations?.” Foreign Affairs 72(3): 31–35.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1998. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. London: Touchstone.

Huntington, Samuel P. 2004. Who are We? The Challenges to America’s National Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Hutton, Alexander. 2014. “‘A belated return for Christ?’: The reception of Arnold J. Toynbee’s A Study of History in a British context, 1934–1961.” European Review of History 21(3): 405–424.

Jerrold, Douglas. (954. The Lie about the West: A Response to Professor Toynbee’s Challenge. London: J. M. Dent.

McNeill, William H. 1989. Arnold J. Toynbee: A Life. New York: Oxford University Press.

Melko, Matthew. 1969. The Nature of Civilizations. Boston: Porter Sargent.

Perry, Marvin. 1982. Arnold Toynbee and the Crisis of the West. Washington, DC: University Press of America.

Sharma, Jyotirmaya. 2013. A Restatement of Religion: Swami Vivekananda and the Making of Hindu Nationalism. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Toynbee, Arnold J. 1922. The Western Question in Greece and Turkey: A Study in the Contact of Civilizations. London: Constable.

Toynbee, Arnold J. 1923. “History.” In The Legacy of Greece edited by R. W. Livingstone, 289–290. Oxford: Clarendon.

Toynbee, Arnold J. 1934. A Study of History, vol. I. London: Oxford University Press.

Toynbee, Arnold J. 1948. Civilization on Trial. New York: Oxford University Press.

Toynbee, Arnold J.1953. The World and the West. New York: Oxford University Press.

Toynbee, Arnold J. 1954a. A Study of History, vol. VII. London: Oxford University Press.

Toynbee, Arnold J. 1954b. A Study of History, vol. VIII. London: Oxford University Press.

Toynbee, Arnold J. 1956a. An Historian’s Approach to Religion. London: Oxford University Press.

Toynbee, Arnold J. 1956b. “A Study of History – What the Book is for: How the Book Took Shape.” In Toynbee and History: Critical Essays and Reviews edited by M. F. Ashley Montagu. Boston: Porter Sargent, 8–11.

Voegelin, Eric. 1956–87. Order and History, vols. I–V. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Samuel Huntington and the American Way of War

- The Color of Institutions: Morality, Unity, or Decay? A Personal Reflection

- Civilization as an Alternative Unit of Analysis in International Relations

- Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine and the Return of Civilisational Politics: An American and French Tale

- Opinion – Nationalism and Trump’s Response to Covid-19

- Does the Public Get What it Wants? The UK Government’s Response to Terrorism