Sometimes thought of as the invisible army, private military and security companies (PMSCs) are part of a global, multi-billion dollar industry. The United States of America along with many other Western and non-Western nations, has made ample use of this private military resource to enhance its military endeavours and promote U.S. national interest. PMSCs, however, are a problematic industry full of contradictions and inherent issues, including an unclear status under international humanitarian law, a poor human rights record, and the fact that they profit off wars. Many of these issues were brought to the public’s attention because of the scandals that surfaced after their copious use in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Despite that, recent administrations, specifically under President Barack Obama, continued to make PMSCs part and parcel of their military efforts abroad. Why? In the course of this paper, I will argue that the U.S. government continues to make use of PMSCs because: a) their deployment does not require authorisation from Congress; b) the companies have strong ties with the political establishment; c) utilising private military, especially in humanitarian missions can be seen as a better option that deploying uniformed personnel; and d) the U.S. might have developed a dependency on PMSCs.

This paper is structured in four distinct sections. Section I provides a working definition of key terms and describes some of the events and mechanisms that allowed PMSCs to become a modern and thriving global industry. Section II exposes some of the intrinsic issues with PMSCs, thus shedding light on why the ample use the U.S. makes of said companies is deemed problematic. Section III provides a snapshot of the usage of PMSCs during Obama’s two terms. Lastly, Section IV deals with some of the possible explanations as per why President Obama continued to utilise PMSCs despite the scandals and issues that became apparent in the first few years of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

This paper aims at exploring and exposing U.S. reliance on PMSCs despite scandals and inherent issues of the industry. There is a multiplicity of reasons to motivate why choosing the U.S. as the focus of this paper. For one, the U.S. Army is generally considered to be the most potent military apparatus on the planet and, as such, their profuse use of private military contractors (PMC) is rather puzzling. If the largest military apparatus outsources part of its military operations, what implications does it have for the rest of the world? Because of this, however, some of the findings of this paper will not and are not meant to be generalizable. Additionally, the U.S. provides a perfect analytical case because of the wealth of literature, government documents, white papers, and opinion pieces readily available online.

Section I

This section provides a working definition of PMSCs, as well as context related to the extent to which they were used at different points in American history. Furthermore, this section is aimed at shedding light on the modern-day configuration of this sophisticated global industry, and debunk some common misconceptions fueled by popular culture.

Not Mercenaries but Kind Of?

Prior to delving into the working definition used in this paper to discuss PMSCs, it is important to review the literature around the difference and commonalities between PMCs and mercenaries. Before becoming a sophisticated global industry, freelance mercenaries were fighters, trained to various degrees, who provided military services in exchange for monetary compensation or land ownership.[1] Freelance mercenaries were directly contracted by governments, rebel groups, and more generally by whomever could afford it.[2] PMSCs, on the other hand, are legal, corporate entities, which provide a professional service, namely soldiers who are highly-trained, extremely organized, and are deemed to be some of the “leading military experts in the world.”[3] The companies serve as an intermediary between the government and the professional soldiers, so that individual soldiers are not directly contracted by the government in the same fashion as their freelance predecessors were.[4] PMSCs offer a wide variety of services, including diplomatic and reconstruction support, business operations, recovery, and military and security activities.[5] The PMSCs’ offerings of military and security services are also quite whole-encompassing, seeing that they provide services ranging from “protecting people (including military personnel, governmental officials, and other high-value targets); guarding facilities;” to “escorting convoys; staffing checkpoints; training and advising security forces; and interrogating prisoners.”[6]

These two characteristics, namely their degree of professionalization and the fact that they are not directly contracted by a government, allow scholars and industry leaders to clearly create separate categories for freelance mercenaries and PMSCs. However, there are several other characteristics that blur the line between the two entities and call into question the distinction that industry professionals often strive to make. Firstly, both entities are fundamentally profit-driven and, as shown hereafter in Section II, this fact is construed by some as fundamentally problematic.[7] Additionally, while PMSCs constitute a multi-billion dollar global industry, not all individual enterprises are large, high-profile firms. Many individual enterprises are “little more than temporary associations operating out of small rented rooms with little more than a telephone and fax machine,” and, thus, in many respects hardly distinguishable from freelance mercenaries.[8]

Since the distinction between freelance mercenaries and PMSCs is so feeble, why is it necessary to differentiate them at all? The most obvious reason relates to the fact that mercenaries are banned by the International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries, also known as the United Nations Mercenary Convention.[9] The Convention was signed in 1989 and officially entered in force in October 2001. Because of the distinction created between mercenaries and PMSCs, the UN Mercenary Convention did not legally apply to PMSCs. Thus, in 2006, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution “prohibiting ‘private companies offering international military consultancy and security services’ from intervening in conflicts or being used against governments.”[10] Yet, many countries who currently make ample use of PMSCS, including the U.S., have simply avoided ratifying and adopting either Convention.[11] The distinction between mercenaries and PMSCs, and the international, legal framework that regulates – or is supposed to regulate – the use of PMCs in war are essential factors to keep in mind in light of the large use of military contractors by the U.S.[12]

A Global Industry: Then and Now

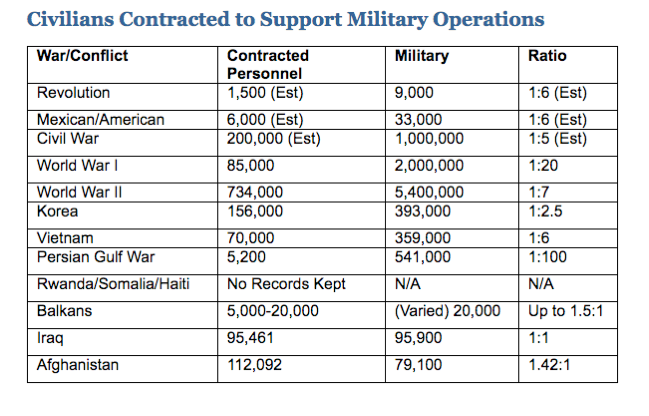

As discussed in the previous sub-section, private militias are not a novel phenomenon per se. In the American context alone, the use of military contracts can be traced as far back as the American Revolution, when privateers constituted approximately 1/6 of the army.[13] American reliance on private militias continued during the Mexican-American War and the Civil War, and well into the 20th and 21st centuries.[14] Figure 1, originally published online by the Defence Procurement Acquisition Policy, a branch of the Department of Defense, provides an overview of U.S. use of PMCs since the Revolution. Thus, while private militias are far from being a new phenomenon, they were used at an unprecedented scale in the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, which, as shown in Section II, allowed for many issues to come to the public’s attention.

Figure 1: Civilians Contracted to Support Military Operations Source: http://www.acq.osd.mil/dpap/pacc/cc/history.html.

Two factors concurrently contributed to the surge in use of private military companies in the past three decades: the end of the Cold War and the so-called “Mogadishu Syndrome.” In the decades following the end of the Second World War, the world underwent a period of “hypermilitarization” with NATO and the Warsaw Pact, which in turn allowed several countries to construct and strengthen the industrial military complex.[15] As the Cold War came to an end, however, many countries downsized their military forces in an effort to curb the financial burden now unnecessarily weighing on their national budget. The U.S. was not unlike other states and, in the immediate post-cold war era reduced its armed forces by thirty-five percent and cut cost by over $100 billion.[16] Because of this, many individuals worldwide who had previously been employed by their respective country’s military apparatus now found themselves looking for new employment opportunities.[17] This well-trained, robust labour pool was instrumental in allowing

PMSCs to become sophisticated global industry. Similarly, during the Cold War it was easier for political elites in the U.S. (and worldwide) to motivate the use of force as the looming Soviet menace posed – or was widely perceived as posing – a direct threat to U.S. national interest and security integrity. However, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, it became increasingly more politically costly for American elites to motivate their involvement in conflicts in far-away regions. The use of PMSCs, thus, provided a relatively easy way to avoid public scrutiny while still achieving operational objectives, something that will be further explored in Section II.

Another key event that contributed to the success of private military companies is the so-called “Mogadishu Syndrome” or “Mogadishu Line.” In 1993, the U.S. led a coalition of states in Operation Restore Hope. The Operation had been sanctioned following the unanimous adoption of United Nations Security Council Resolution 794, which authorised the use of “all necessary means to establish as soon as possible a secure environment for humanitarian relief operations in Somalia.”[18] However, during a firefight on October 1993, 18 American Rangers and 312 Somali were killed, causing a public uproar, as well as the interruption of the mission altogether.[19] Following the tragic events of Mogadishu, many Americans began to call into question the necessity to get involved in conflict for humanitarian reasons, especially when American interests were not directly at stake.[20] Thus, what is now called the Mogadishu Line or the Mogadishu Syndrome refers to the unwillingness by governments to intervene with “boots on the ground” for humanitarian purposes rather than for national interest. In essence, both the end of the Cold War and the Mogadishu Syndrome have contributed to making private military companies a growing, thriving industry. The end of the Cold War, and the demilitarization that followed, created a large pool of highly-skilled professionals that PMSCs gladly tapped in for lucrative purposes. Similarly, the demise of the Soviet threat and the casualties suffered by the U.S. in Mogadishu made the American public less inclined to support military engagement abroad, which in turn induced political leaders to become extremely sensitive to casualties as well.[21]

Today, private military enterprises constitute a multi-billion dollar industry extensively used by developed and developing countries alike. In 2011, the Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan estimated that at least $117 billion has been spent on private contractors alone since October 2001.[22] When factoring in the value of funds obligated for “contingency contracts for equipment, supplies, and support services,” the total expenditure raises considerably reaching “$154 billion for the Department of Defense, $11 billion for the Department of State, and $7 billion for the U.S. Agency for International Development.”[23] Furthermore, on top of the unprecedented scale to which PMSCs have been used, what constitutes a discontinuation from the past is also “the numbers of companies, the scope of services offered, and the visibility of their operations.”[24] A report from 2008 estimated that “at least 310 companies based in numerous states have contracted or subcontracted to carry out security functions for the USA in Iraq.”[25] Thus, the U.S. government has already committed several billion dollars supporting an industry that, as shown in Section II, is deeply flawed.

Seeing that the U.S. government and other countries make such ample use of PMSCs, it is worth mentioning how public perception of private militias has been shaped by mercenaries as portrayed in the film industry. Interestingly, in the mainstream media and among the public, the words mercenaries and private military companies are used interchangeably. Bjork and Jones argue that “the conventional image of the 20th-century mercenary is the misanthropic ex-military type, surreptitiously dropping into African civil conflicts in search of profit and adventure.”[26] Movies such as The Expendables which portray valiant, American mercenaries contributing to the success of military operations in various contexts, have contributed to fueling this public misconception. Because of this, the public and, at times, the media have tended to romanticize the so-called mercenaries, which in turn has prevented PMSCs regulations to become a legislative priority in the U.S.[27] Of course, this relatively-positive image is a minor reason why the U.S. and the international community have failed to regulate this thriving global industry; yet, it is still a factor worth mentioning.[28]

Section II

As the raison d’être of this paper is uncovering why the U.S. still makes ample use of PMSCs despite their many issues, this section is aimed at exploring what some of these issues are. As shown hereafter, PMSCs are problematic partly because of intrinsic dynamics, such as the fact that they profit from war, and partly because of weak regulations.

Profiting from War

The first and, perhaps, must obvious issue with private military companies relates to the fact that they profit from war. As established in Section I, this feature is one of the primary commonalities between mercenaries and PMSCs. Yet, it is worth asking, is there something inherently bad in profiting from war? The answer, in my opinion, is yes, since earning wages from conflicts generates perverse incentives, as shown hereafter. However, it is important to mention that PMSCs are far from being the only market-driven force benefitting from wars. The arms industry, for example, is at the core of the industrial military complex and generates several billions of dollars per year. The U.S. Army, in a sense, stays in business because of the existence of conflicts and threats to American national interest.[29] Nevertheless, there is a specific set of incentives that affects the private military industry because of the fact it is an industry rather than a branch of the U.S. government. For one, conceding that private entities aid the military in military operations shatters the Weberian idea of having a state as “the sole repository of the legitimate coercive force.”[30] Additionally, as Akcinaroglu and Radziszewski argue, PMSCs benefit from the presence of security threats, regardless of who the threat is towards.[31] Similarly, since the companies are ultimately accountable to their shareholders, their goals, objectives and values do not always reflect those of the government that hired them.[32] PMSCs play a role in exacerbating conflicts as they have been known to support opposing sides in a conflict.[33] Similarly, because they are ultimately profit-driven, corporate entities only accountable to their shareholders, they can provide services to both legitimate actors, such as governments, as well as illegitimate actors, namely rebel groups and terrorists. In this sense, Taulbee argues that cutting-edge, military expertise “can be purchased, if the buyer has the appropriate contacts and funds.”[34]

Another problem directly related to the profit-driven nature of private military enterprises relates to the demographic composition of contractors hired. Because PMSCs are ultimately market-driven, they are incentivised to hire whomever possess the skill-set necessary to be a contractor. While the minimum requirements vary from company to company, most contractors recruited come from the developing world.[35] In turn, according to De Nevers, the multi-ethnic composition of private militias makes them look increasingly more like mercenaries which, as noted in the previous section, are supposed to be banned. In a more pragmatic sense, the diversity in backgrounds of private contractors could have an impact on the values they hold and how they operate in conflict zones.[36] More specifically, some scholars have noted that, as many contractors originate from the developing world, their values might not align with what is considered the standard in the U.S. military – Western values.[37] These sentiments have been echoed by the Senate Committee on Armed Services, Inquiry into the Role and Oversight of Private Security Contractors which deemed the “lax vetting of employees” a matter of concern.[38] In the specific case of Iraq, the 2008 census by the U.S. Army Central Command found that: “the 190,200 contractors in Iraq included about 20 percent (38,700) U.S. citizens, 37 percent (70,500) Iraqis, and 43 percent (81,006) third country nationals.”[39] The staggering number of locals hired invites me to further delve into implications of hiring Iraqi contractors while carrying out a war in Iraq. On the one hand, their knowledge of local costumes, locations, and contacts can positively impact the militia’s overall effectiveness.[40] On the other hand, they might have objectives that are not consistent with those of the U.S. Army. In one instance, Afghan contractors hired to provide convoy security to the U.S. military in Afghanistan allegedly funneled funds to the Taliban thus undermining the U.S. core mission in Afghanistan.[41]

Neither Meat nor Fish: IHL and the Private Military Contractor

Another fundamentally problematic issue with PMSCs relates to their ambivalent status under current international humanitarian law (IHL). Firstly, it is important to note there is a general consensus towards considering PMSCs and their employees as non-combatants – civilians.[42] The distinction between civilians and combatants is at the core of IHL and serves as a regulatory framework to limit individuals’ behaviour in warzones. In a conflict, civilians are supposed to be protected by direct attacks for as long as they refrain from taking active part in the conflict.[43] Combatants, on the other hand, must respect a set of criteria including: abiding to the laws of war; carrying weapons openly; being recognizable through a uniform or other signage; and, operating under a clear command structure.[44] Additionally, those accorded combatant status can benefit from “combatant privilege” meaning that, if captured, they would (should) be treated as prisoners of war rather criminals.[45]

The distinction between civilians and combatants, especially in the case of PMCs, is not as clear cut as it seems. To begin, while private contractors are generally considered civilians, they often do not respect the norm of refraining from joining the conflict in a combat role. So far, Petersohn argues, PMSCs advocates have been able to bend the laws by altering the perception of “PMSCs’ use of force not [as] combat, but rather individual self-defence,” thus making it a legitimate and lawful practice.[46] However, controversies abound. The Blackwater (now called Academi) incident of 2007 in Nisour Square, Baghdad is a revealing example of how murky the distinction between civilians and combatants can be with regards to PMSCs. On September 2007, some Blackwater contractors allegedly opened fired on civilians in Baghdad, killing seventeen civilians and injuring many others.[47] While Blackwater spokespeople declared the attack was an act of self-defence in retaliation to a car-bombing by an insurgent group, both Iraqi and US investigations confirmed that the guards fired without provocation.[48] This incident sheds light on the problematic classification of PMCs as civilians. In fact, in this specific case, Blackwater contractors appear to have violated IHL and could thus be tried for war crimes.[49] It is essential to keep in mind that not all contractor engage in combat. Nevertheless, cases like that of Blackwater rightfully rise concerns regarding the lack of appropriate regulations to classify PMCs in conflict zones.

Seeing that PMCs status as civilians is rather ambiguous, could they be classified as combatants? Not exactly. They do not comply with the definition of combatant presented above, which can be considered the most minimal definition allowed within the IHL framework. First, because they are not formally considered part of the U.S. military, they do not respond to the U.S. chain of command and it is unclear to what extent “a stable, fixed hierarchy within the relevant company” is present.[50] As such, they do not seem to comply with the requirement of operating under a clear command structure. Additionally, while most PMCs have a look that some consider “badass” or “tough” which makes them, at times, distinguishable from civilians, they cannot be clearly distinguished from one another.[51] Therefore, monitoring their action and unsuring accountability becomes a herculean task. It is true, however, that since the Blackwater incident, the U.S. State Department requires U.S. contractors to adopt “identification requirements, along with stricter audio and video recording requirements.”[52] Even so, PMCs fail to meet the criteria of being unequivocally discernable from civilians and other combatants. Because of their fluidity, thus, they still hold an unclear status within the current IHL framework.

Catch Me If You Can: Human Rights Abuses and Lack of Regulations

Lastly, PMSCs have enraged and horrified the world because of alleged misconduct and gross human rights violations. While this point is inherently intertwined with their unclear status under IHL, I believe it deserve a sub-section in its own rights. In the previous paragraphs, I discussed Blackwater employees’ involvement in a firefight in Nisour Square which took the lives of several civilians. The allegations are not limited to this event. Prior to the incident, PMCs were involved in torturing Iraqis – both civilians and combatants – within the closed walls of the Abu Ghraid prison, in Iraq. Analysts and scholars believe that it is unclear to what extent the practice has stopped since it surfaced in the news. While PMSCs’ disregard for human rights is in and of itself concerning, it is important to note that national governments, as well as the international community, have not been able to put in place regulations to limit the PMCs’ “freedoms.”

Since 2000, when the Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act was passed, the U.S. government has tried to have its national legislation reflect more accurately the realities of their wars abroad.[53] In 2004, the Act was expanded so as to allow contractors recruited by the Department of Defence to be legally prosecuted in the eventuality they committed crimes that would result in more than one year of imprisonment if committed on U.S. soil.[54] However, it is important to remember that the Department of Defence is not the only branch of U.S. government which made use of PMCs. Thus, such measures would not apply to all PMCs employed by the U.S. government. Lastly, in 2007, Congress passed more comprehensive laws, in the form of an amendment to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, to subject PMCs to the system of court-martials.[55] Even so, few individuals have been prosecuted to date, due to inefficiencies, lack of oversight, and failure to effectively monitor contractors abroad.[56]

The international community has also contributed to the regulatory effort, with mixed results. In 2008, the Montreux document was created as part of a joint initiative between the Swiss government and the International Committee of the Red Cross. The document was meant to establish standards for best practises and behaviours; yet, not only did it not envision any enforcement mechanisms but it also failed to garner significant international support, as it was only signed by forty-nine countries.[57] The International Code of Conduct for Private Security Service Providers (ICoC), on the other hand, is a more ambitious initiative aimed at outlining obligations and rules around the “use of force and vetting procedures for contractors and subcontractors.”[58] While the ICoC was signed by over 700 companies, it also failed to incorporate enforcement mechanisms, thus putting into question its effectiveness.[59] Significantly, under certain circumstances, PMCs could be tried at the International Criminal Court (ICC). If, for example, they violated the principle of distinction and they were either a national of, or committed a violation on the territory of an ICC signatory, they could be tried for war crimes in their country’s national courts, or because of the principle of complementarity, at The Hague.[60] As such, it is clear that the international community and, to an extent, the U.S. government have tried to set up regulations so as to ensure accountability for crimes committed by PMCs. However, their efforts have been hindered by a lack of engagement by the whole international community, as well as by inherent problems in monitoring PMCs. Similarly, as shown in Section IV, it can be argued that states like the U.S. might have some interests in maintaining regulations around the lawful use and behaviour of PMCs lax.

Section III

Thus far, this paper has analyzed the rise of PMSCs as well as the negative impacts and inherent issues. This section is specifically dedicated to estimate the extent to which they have been used in recent years, despite the scandals and issues that were brought to the public’s attention during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Based on the evidence presented in Section I and II, it is clear that, while many issues relevant to PMSCs predated the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, these two conflicts not only saw an unprecedented reliance by the U.S. on private contractors, but also generated a series of scandals and controversies – the Nisour Square incident, for example – that made the public and the international community question the U.S. overreliance on this resource. Because of this, it would be expected by the subsequent administrations, namely the Obama Administration, to sever or at least loosen their connection with PMSCs. That is not the case. At the end of President Obama’s second term, Foreign Policy reported that his Administration made an “unprecedented use of private contractors.”[61] Zenko noted, in fact, that the number of PMCs outnumbered three to one uniformed personnel in Afghanistan in 2015.[62] For comparison, during the last quarter of 2007, the U.S. military counted 24,056 armed forces and 29,473 PMCs in Afghanistan.[63] In the second quarter of 2013, the number of contractors raised to 117,227 while the number of uniformed personnel raised to 88,200.[64] Thus, the Congressional Research Service report clearly shows how President Obama increased the number of contractors on the ground, despite the scandals and issues that surfaced during the tenure of previous Administrations.

Interestingly, during Obama’s two terms, the number of private contractors on a U.S. government payroll increased in several departments. In 2015, the U.S. Government Accountability Office estimated that 55% of the Office of the Secretary of Defence employees were private contractors.[65] Similarly, the commander of the U.S. Cyber Command declared that 25% of the Command’s employees were contractors. As such, it is important to remember that PMCs, were and still are used in several different Departments, both at home and abroad. Furthermore, the net amount of dollars that the U.S. has spent on private contractors has also increased during Obama’s tenure. The amount of total federal budget devoted to private contractors peaked in 2010 reaching over $600 billion.[66] In 2015, the Pentagon alone paid over $270 billions to private military companies. Lastly, a 2010 report uncovered how the Department of Defense, under Obama, hired warlords to provide security services.[67]

As such, the Obama Administration, the first distinct administration that took office after the negative impact of PMCs were uncovered in Iraq and Afghanistan, did not disentangle itself this global industry; on the contrary, it seemed to increase its reliance of PMSCs. What can explain that?

Section IV

Thus far this paper has provided an account of the rise of PMSCs in the modern context and, most importantly, justifications as per way they are deemed to be a problematic industry. Section III explored the recent political context and established that, despite the negative impacts and inherent issues, the Obama Administration still made ample use of PMSCs. This section is dedicated to uncovering why, despite the issues mentioned in Section II, the U.S. would still heavily rely on PMSCs for its war effort.

Out of Sight, Out of Mind?

As explored in Section I, the disintegration of the Soviet Union marked the cessation of a perceived ongoing threat to U.S. national security. As Washington’s nemesis cessed to cast its dark shadow all around the globe, it became increasingly difficult for the U.S. political elite to motivate interventions in faraway lands. “American political leaders” Taulbee writes “have become extremely sensitive to causalities associated with overseas initiatives.”[68] Contracting PMSCs, as such, provides the U.S. military with an opportunity to “minimize the commitment and exposure” of American troops, while still reaching operational objectives.[69] Interestingly, while most PMCs engage in security operations, it is unclear to what extent the U.S. military makes use of them in combat roles. In the 1990s, some PMSCs such as Sandline International and Executive Outcomes have been known to engage in combat roles in Angola and Sierra Leone.[70] However, these events generated public outrage against contractors carrying out offensive missions, so much so that some academics began to hypothesise a norm might be emerging against the use of PMCs in combat roles.[71] Currently, industry representatives in the U.S. and elsewhere maintain that “none of the companies” are meant to, or engaged in, operations that involve combat.[72] Leander, however, has suggested that their level of sophistication, coupled with ties with the political establishment, has allowed for combat operations to escape the public’s gaze.[73]

The debate around the legitimacy of combat operations by PMSCs is especially poignant because it is this very feature that still makes them appealing to Washington and problematic as a military measure. In fact, establishing whether PMCs are deployed in a combat capacity is significant because such mission can be – and have been – authorised without the oversight of Congress. In the case of the Iraq war, the political elite capitalised on the fact that total transparency and direct authorisation from Congress were not necessary to authorise a surge in private militias.[74] President George WQ. Bush also benefitted from the fact that little to no information was disclosed to the public at the time of the surge.[75] “As the insurgency grew in Iraq” Avant and De Nevers note “the United States mobilized 150,000 to 170,000 private forces to support the mission there, all with little or no congressional or public knowledge – let alone consent.”[76] President Obama, similarly, did not require the authorisation of Congress to deploy more private militias in Iraq and Afghanistan and, on the contrary, increased the number of PMCs supporting the U.S. military operations during his tenure.

Furthermore, there are reason to believe that, had President Bush consulted Congress for approval on the surge in PMCs, his request would have been denied seeing that an increase of boots of on the ground of “only” twenty thousand troops was promptly denied in 2007.[77] The American electorate, as argued before, became increasingly sensitive to the issue of military casualties. President Obama, who inherited the wars, in a sense, had no choice but to reply of PMCs to try achieving military objectives while still respecting the wishes of his electorate.

The use the U.S. government has thus far made of PMSCs in Iraq and Afghanistan points to the fact that Washington might outsource contractors because of the loophole that allows them to escape oversight from Congress. The cases presented, in fact, point to the fact that avoiding accountability and authorisation from Congress could be reasons why the Obama administration continued to increase the number of contracted personnel on the ground despite the issues that surfaced prior to his election.

Your Friend is Our Friend: The Revolving Door Effect and Lobbying

Because PMSCs are part and parcel of a multi-billion-dollar industry, it would be naïve to underestimate to strength of their ties with the political establishment. Before delving further into this topic, I would like to clarify that making normative considerations regarding the ethics of this connections is beyond the scope of this paper. As such, this paper merely explores industry-government ties as an explanation for the persistence of PMSCs and refrains from incorporating moral considerations. Having said that, the ties that PMSCs and Washington share are quite substantive. For one, cross over from the public to the private sector is rather prevalent. In the case of Blackwater alone, the Chief Operations Officer for the Blackwater’s parent company, Joseph Schmitz, previously served as the Pentagon’s Inspector General. Similarly, the State Department counterterrorism coordinator and Director of the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center, Cofer Black, moved on to become Blackwater Vice-Chair. The transition of former civilian and military officers into the public sector is called the revolving door effect. Because of this movement, PMSCs acquire deep connections into several branches of the U.S. government and are, thus, able to assert a large degree of influence.[78] Additionally, former officials also contribute to making PMSCs hubs of military and strategic expertise – this explains their success as a cutting-edge industry.[79]

As noted in Section II, many of the issues that affect PMSCs relate to the lack of appropriate regulations. The political ties that companies have, coupled with effective lobbying efforts can, in turn, explain the lack of effective legislation. Lobbying has been a powerful instrument for many industries, including the private military one, to prevent the government from, quite literally, interfering in their business. The founder of Blackwater Eric Prince has, for example, donated $250,000 to President Donald Trump to support his campaign.[80] Prince, however, has donated several millions of dollars to the Republican Party since 1989.[81] Due to their influence in Washington, PMSCs have been able to block unfavourable bills in congress as well. For example, in 2001, DynCorp, through two of its subsidiary firms, was able to prevent the passing of a bill that would require federal agencies to justify the use of PMSCs on the basis of cost-saving calculations.[82] Thus, the revolving door effect and effective lobbying efforts by PMSCs are also reasons why the U.S. government continues to make ample use of them despite the negative effects outlined in Section II.

The Bad, the Ugly and….the Good?

While strong ties between the political establishment and industry leaders, and the ability to avoid congressional oversight are valid reasons to continue to rely on PMSC, it is important to note that the Obama administration might have also taken into consideration the potential positive effects of outsourcing certain aspects of their military operations. The reasons presented hereafter mostly apply to deployment of troops for humanitarian purposes and, thus, fail to explain in full what would induce their continued reliance in Iraq and Afghanistan. However, it could contribute to explaining the more general increase in reliance of contracted personnel. Baker and Pattison, for example, argue that the use of PMSCs could allow for countries to spread more evenly the cost of military operations for humanitarian purposes.[83] In a similar fashion, they question the ethics of risking lives of American soldiers who joined the army to protect their country for the sake of saving lives of “others.”[84] In this sense, they suggest that PMSCs should be preferred for risky humanitarian operations in lieu of American conscripts.[85] It is difficult to discern whether President Obama’s motivation were necessarily driven by such ethical considerations. However, this lens sheds some light on the potential positive aspects of making use of PMSCs and include some considerations that could be made in the future to justify U.S. reliance on the private industry for its military endeavours.

Can’t Live With ‘em, Can’t Live Without ‘em

The last contributing explanation to the fact that the Obama Administration has continued to utilize PMCs relates the potential dependency the government might have developed. The U.S. has indeed relied for several years on the use of PMSCs to achieve its operational goals. As shown in Section I and II, for the past few decades, the U.S. has integrated private military forces into its army in both military and security capacities. As shown in this paper, after the end of the Cold War, the American public became more sensitive to casualties and less inclined to accept military operations when national interests were not directly at stakes. A mismatch between the will of the people and U.S. foreign policy priorities emerged, so that President Obama who, in a sense, inherited this legacy of reliance on private companies, could have simply been forced to continue on utilizing PMSCs. Of course, this explanation does not explain the surge of private contractors of 2010. However, it can contribute to explaining more generally why President Obama continued to rely on PMSCs.

Conclusion

This paper analysed the rise and diffusion of PMSCs in their capacity as a multi-billion dollar industry. Despite not being mercenaries, they inherited several issues that make their use equally as problematic. From the lack of appropriate regulations to their unclear status under IHL, to the numerous human rights abuses, problems abound. Though many of these issues are inherent to the industry and thus predated the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, they rose to public prominence in the early 2000s and allowed for the general public to get a better understanding of the foundational issues with the industry. However, President Obama, in the aftermath of several human rights scandals involving PMCs, continued to contract private militaries, and actually increased their use. This paper, thus, explored what factors could have led President Obama to continue relying on PMSCs. The lack of congressional oversight, the strong public-private ties, the potential positive side effects, as well as a legitimate dependency on private militia by the U.S. are all factors that have contributed to President Obama’s course of action.

Bibliography

[1] Seden Akcinaroglu, and Elizabeth Radziszewski, “Private Military Companies, Opportunities, and Termination of Civil Wars in Africa,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 57, no. 5 (2013): 795-821.

[2] Gail M. Gerhart, Abdel-Fatau Musah, and J. Kayode Fayemi, “Mercenaries: An African Security Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs 80, no. 2 (2001): https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/capsule-review/2001-03-01/mercenaries-african-security-dilemma.

[3] Seden Akcinaroglu and Elizabeth Radziszewski, “Private Military Companies, Opportunities, and Termination of Civil Wars in Africa.” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 57 no. 5 (2012): 795 – 82.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Nils Rosemann, “Code of Conduct: Tool for Self-Regulation for Private Military and Security Companies,” Geneva Ctr. for Democratic Control of the Armed Forces, Occasional Paper No. 15 (2008): https://www.dcaf.ch/sites/default/files/publications/documents/OP15_Rosemann.pdf.

[6] Emanuela-Chiara Gillard, “Business Goes to War: Private Military/Security Companies and International Humanitarian Law”, International Review of the Red Cross 88, no. 863 (2006): 525-526.

[7] Gail M. Gerhart, Abdel-Fatau Musah, and J. Kayode Fayemi, “Mercenaries: An African Security Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs 80, no. 2 (2001): https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/capsule-review/2001-03-01/mercenaries-african-security-dilemma.

[8] James Larry Taulbee, “The Privatization of Security: Modern Conflict, Globalization and Weak States,” Civil Wars 5, no. 2 (2002): 1-24.

[9] Renée De Nevers, “Private Security Companies and the Laws of War,” Security Dialogue 40, no. 2 (2009):169-190.

[10] Doug Brooks. “In Search of Adequate Legal and Regulatory Frameworks,” Journal of International Peace Operations 2, no. 5 (2007): 4–5.

[11] Alexander G. Higgins, “US rejects UN mercenary report,” USA Today, 17 October 2007, Access Date 01 April 2018. https://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/world/2007-10-17-3392316246_x.htm.

[12] In this regard, it is important to keep in mind that the U.S. is not the only country to rely on PMSCs. However, as this paper is limited in scope to the case of the U.S., I will specifically focus on American involvement with private militias.

[13] Alexander Tabarrok, “The rise, fall, and rise again of privateers,” Independent Review 11, no. 4 (2007): 566-567

[14] Carey Luse, Christopher Madeline, Landon Smith, and Stephen Starr, “An Evaluation of Contingency Contracting: Past, Present, and Future,” Naval Postgraduate School, MBA Professional Report, (2005). http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a574440.pdf.

[15] P. W. Singer, “Corporate Warriors: The Rise of the Privatized Military Industry and Its Ramifications for International Security,” International Security 26, no.3 (2001): 56.

[16] David A. Wallace, “International Code of Conduct for Private Security Service Providers,” International Legal Materials 50, no. 1 (2011): 89-104.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Security council resolution 794

[19] Andrew Purvis, “The Somalia Syndrome,” Time Magazine, 22 May 2000, Access Date: 01 April 2018, http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2050145,00.html.

[20] Thomas G. Weiss, “Overcoming the Somalia Syndrome— “Operation Rekindle Hope?”” Global Governance 1, no. 2 (1995): 171-87.

[21] Taulbee, “The Privatization of Security: Modern Conflict, Globalization and Weak States,” 1-24.

[22] “At What Risk? Correcting Over-Reliance on Contractors in Contingency Operations,” Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan, second interim report to congress, Washington, 2011.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Taulbee, “The Privatization of Security: Modern Conflict, Globalization and Weak States,” 1-24.

[25] “Agencies Need Improved Financial Data Reporting for Private Security Contractors, Report 09-005.”. Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction (SIGIR), 2008, Access Date: 01 April 2018. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a489037.pdf.

[26] Kjell Bjork and Richard Jones. “Overcoming Dilemmas Created by the 21st Century Mercenaries: Conceptualising the Use of Private Security Companies in Iraq.” Third World Quarterly 26, no. 4/5 (2005): 777-96.

[27] Anthony Mockler, The New Mercenaries (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1985), 9.

[28] The documentary Shadow Company (2006) provides a crude but candid overview of the role that PMSCs are playing on the global stage and in conflict zones. The documentary is available for free on Youtube.

[29] This applies to every Army.

[30] Bjork Jones. “Overcoming Dilemmas Created by the 21st Century Mercenaries: Conceptualising the Use of Private Security Companies in Iraq.” 777-96.

[31] Akcinaroglu and Radziszewski, “Private Military Companies, Opportunities, and Termination of Civil Wars in Africa.” 795 – 82.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Anna Leander, “The Market for Force and Public Security: The Destabilizing Consequences of Private Military Companies.” Journal of Peace Research 42, no. 5 (2005): 605-22.

[34] Taulbee, “The Privatization of Security: Modern Conflict, Globalization and Weak States,” 1-24.

[35] De Nevers, “Private Security Companies and the Laws of War,” 169-190.

[36] Deborah D. Avant, and Renée De Nevers. “Military Contractors & the American Way of War.” Daedalus 140, no. 3 (2011): 88-99.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Senate Committee on Armed Services, “Inquiry into the Role and Oversight of Private Security Contractors in Afghanistan,” 111th Cong., 2nd sess., 28 September 2010, Access Date: 01 April 2018. http://info.publicintelligence.net/SASC-PSC-Report.pdf.

[39] “Contractors’ Support of U.S. Operations in Iraq,” Congressional Budget Office 2008, Access Date: 01 April 2018, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/96xx/doc9688/08-12-iraqcontractors.pdf.

[40] Avant and De Nevers. “Military Contractors & the American Way of War.” 88-99.

[41] Dexter Filkins, “Convoy Guards in Afghanistan Face an Inquiry: U.S. Suspects Bribes to Taliban Forces,” The New York Times, 7 June 2010, Access Date: 01 April 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/07/world/asia/07convoys.html.

[42] Michael N. Schmitt, “Humanitarian Law and Direct Participation in Hostilities by Private Contractors or Civilian Employees,” Chicago Journal of International Law 5 no. 2 (2004): 526-527.

[43] Renée De Nevers, “Private Security Companies and the Laws of War” Security Dialogue 40, no. 2 (2009): 169-190.

[44] The Hague Conventions provides four criteria that armed groups must meet to qualify for combatant status; the Geneva Conventions list six. Those presented here are the provisions common to both.

[45] De Nevers, “Private Security Companies and the Laws of War” 169-190.

[46] Ulrich Petersohn, “Reframing the Anti-Mercenary Norm: Private Military and Security Companies and Mercenarism.” International Journal 69, no. 4 (2014): 475-93.

[47] Sabrina Tavernise and James Glanz, “Iraqi Report Says Blackwater Guards Fired First”, New York Times, 19 September 2007, Access Date: 01 April 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/19/world/middleeast/19blackwater.html.

[48] Ibid.

[49] De Nevers, “Private Security Companies and the Laws of War” 169-190.

[50] Schmitt, “Humanitarian Law and Direct Participation in Hostilities by Private Contractors or Civilian Employees,” 526-527, 530.

[51] Ibid. 530.

[52] US Department of State, 2007. Report of the Secretary of State’s Panel on Personal Protective Services in Iraq, October 2007; available at http://www.cfr.org/publication/14792/ report_of_the_secretary_of_states_panel_on_personal_protective_services_in_iraq.html (accessed 13 November 2007).

[53] Jennifer Elsea, Moshe Schwartz and Kennon H. Nakamura, “Private Security Contractors in Iraq: Background, Legal Status and Other Issues” Congressional Research Services, 25 August 2008, Access Date: 01 April 2018. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RL32419.pdf.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ibid, 25-26

[56] Reema Shah, “Beating Blackwater: Using Domestic Legislation to Enforce the International Code of Conduct for Private Military Companies.” The Yale Law Journal 123, no. 7 (2014): 259-573.

[57] Amol Mehra, “Bridging Accountability Gaps – The Proliferation of Private Military and Security Companies and Ensuring Accountability for Human Rights Violations,” Pacific McGeorge Global Business & Development Law Journal 22, no. 2 (2010): 323-328.

[58] Whitney Grespin, “An Act of Faith: Building the International Code of Conduct for Private Security Providers,” Diplomatic Courier, 19 July 2012, Access Date: 01 April 2018. https://www.diplomaticourier.com/2012/07/19/an-act-of-faith-building-the-international-code-of-conduct-for-private-security-providers/.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Hans Born and Anne-Marie Buzatu. “New Dog, Old Trick: An Overview of the Contemporary Regulation of Private Security and Military Contractors.” and Peace 26, no. 4 (2008): 185-90.

[61] Micah Zenko, “Mercenaries Are the Silent Majority of Obama’s Military,” Foreign Policy, 18 May 2016, Access Date: 01 April 2018. http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/18/private-contractors-are-the-silent-majority-of-obamas-military-mercenaries-iraq-afghanistan/.

[62] Micah Zenko, “The New Unknown Soldiers of Afghanistan and Iraq,” Foreign Policy, 29 May 2015, Access Date: 01 April 2018, http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/05/29/the-new-unknown-soldiers-of-afghanistan-and-iraq/.

[63] Heidi M. Peters, Moshe Schwartz and Lawrence Kapp, “Department of Defense Contractor and Troop Levels in Iraq and Afghanistan: 2007-2017,” Congressional Research Services, 28 April 2017, Access Date: 01 April 2019. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R44116.pdf.

[64] Ibid.

[65] “DOD Needs to Reassess Personnel Requirements for the Office of Secretary of Defense, Joint Staff, and Military Service Secretariats,” United States Government Accountability Office, January 2015, Access Date: 01 April 2018. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-10.

[66] “Annual Review of Government Contracting,” Bloomberg Government, 2015, Access Date: 01 April 2018. https://www.ncmahq.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/pdfs/exec15—ncma-annual-review-of-government-contracting-2015-edition.

[67] John F. Tierney, “Warlord, Inc. Extortion and Corruption Along the U.S. Supply Chain in Afghanistan,” Subcommittee on National Security and Foreign Affairs Committee on Oversight and Government Reform U.S. House of Representatives, June 2010, Access Date: 01 April 2018. http://www.cbsnews.com/htdocs/pdf/HNT_Report.pdf.

[68] Taulbee, “The Privatization of Security: Modern Conflict, Globalization and Weak States,” 1-24.

[69] Ibid.

[70] P. W. Singer, Corporate Warriors: The Rise of the Privatized Military Industry. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003): 101-118

[71] Sarah Percy, “Morality and Regulation,” in Simon Chesterman & Chia Lehnardt, eds, From Mercenaries to Market: The Rise and Regulation of Private Military Companies. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007): 11-28.

[72] Bruce Falconer, “Blackwater’s Man in Washington,” Mother Jones, 25 September 2007, Access Date: 01 April 2018. http://www.motherjones.com/washington_dispatch/2007/09/blackwater-contractors-doug-brooks.html.

[73] “Leander, “The Market for Force and Public Security: The Destabilizing Consequences of Private Military Companies.” 614.

[74] Avant and De Nevers. “Military Contractors & the American Way of War.” 88-99

[75] Ibid.

[76] Ibid.

[77] Ibid.

[78] Fabien Mathieu and Nick Dearden. “Corporate Mercenaries: The Threat of Private Military & Security Companies.” Review of African Political Economy 34, no. 114 (2007): 744-55.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Brennan Weiss, “Meet Erik Prince, former Navy SEAL and founder of the most notorious security contractor who Steve Bannon wants to run for Senate,” Business Insider, 9 October 2017, Access Date: 01 April 2018. http://www.businessinsider.com/erik-prince-bio-photos-blackwater-spy-navy-seal-steve-bannon-senate-2017-10.

[81] Jeremy Scahill, “Blood is thicker than Blackwater,” The Nation, 8 May 2006, Access Date: 01 April 2018, https://www.thenation.com/article/blood-thicker-blackwater/ ; see also opensecrets.org for an up-to-date list of donations made by Eric Prince to the Republican Party.

[82] P. W. Singer, Corporate Warriors: The Rise of the Privatized Military Industry. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003.

[83] Deane-Peter Baker and James Pattison. “The Principled Case for Employing Private Military and Security Companies in Interventions for Human Rights Purposes.” Journal of Applied Philosophy 29, no. 1 (2012): 1-18.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Interestingly, it does not really matter whether the PMCs are American nationals or not. What matters is that they had a chance to decide to get involved in a humanitarian mission specifically.

Written by: Tea Cimini

Written at: University of Toronto

Written for: Dr. Mark Kersten

Date written: April 2018

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Outsourcing Security at Sea: Constructivism and Private Maritime Security Companies

- Private Military Companies and Sacrifice: Reshaping State Sovereignty

- Mercenaries of Peace: The Role of Private Military Contractors in Conflict

- Legal ‘Black Holes’ in Outer Space: The Regulation of Private Space Companies

- Australia, China, and the Darwin Port Lease as a Public-Private Partnership

- Historical Institutionalism Meets IR: Explaining Patterns in EU Defence Spending