The Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia[1] (FARC) declared their insurgency in 1964 and did not sign a peace agreement with the Government of Colombia (GoC) until 2016. This qualifies the FARC insurgency as one of the longest running in history (Leech, 2011). Through fifty-two years of government attacks, terrible defeats, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and through the demobilization or defeat of many sister movements, the FARC persisted. In this paper, I will attempt to account for this persistence. First, however, I will provide a short history of the insurgency. Then I will argue that the persistence of the FARC is primarily due to 1) the Colombian government’s failure to cultivate legitimacy with its people, and 2) the government’s misidentification of the center of gravity in the conflict. To a lesser degree, this persistence is also due to 3) the ideological commitment of the FARC, and 4) the absence of safety guarantees for FARC members in the event of demobilization.

A Brief History of the FARC

According to Mark Bowden (2001), April 9, 1948 was a watershed date for Colombia. In Bogotá, the Ninth Inter-American Conference was in session to sign the charter of the Organization of American States (OAS). A great effort had been made by the ruling Colombian Conservative Party to make the city appear stable and prosperous for foreign dignitaries like American Secretary of State George C. Marshall. However, the fresh paint and newly cleaned streets were attempting to mask the intense tensions building between the ruling oligarchs of the Conservative Party and the Colombian Liberal Party, which had competed for power since 1848 (Sioneriu, 2018).

According to Henry Mance (2008), friction between these two camps was hardly new. In fact, these political parties had been at war sporadically since the days of Simón Bolívar, with twelve major conflicts fought before 1902. In these conflicts, the Conservative Party generally pushed for more centralization, while the Liberal Party pushed for less (Bruce et al., 2010). From 1902 to the early 1940s, however, the country had been relatively peaceful and was considered an, “example of democratic stability in Latin America” (Mance, 2008). Bowden (2001) explains that renewed tension between these camps built throughout the 1940s however, due to an economic downturn that led to inflation, unemployment, and hunger for Colombia’s poor. These circumstances allowed a dissident Liberal politician, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán Ayala, to take over the Liberal Party and transform it (temporarily) from a party representing the interests of an elite oligarchy to one representing the poor masses (Sioneriu, 2018). This takeover morphed the Conservative-Liberal rivalry from one of petty disagreements between wealthy elites into one based on the legitimate grievances of the poor, which were 1) the fact that three percent of landholders owned over half of all agricultural land, 2) the lawlessness that resulted from the failure of the state to project its authority to the countryside, and 3) the lack of official political representation for non-elites (Felbab-Brown, 2009).

As the 1940s progressed, poor laborers across the country organized in attempts to secure better livelihoods; the state responded with repression, which included summary executions and massacres (Borch & Stuvoy, 2008; Bowden, 2001). By April 9, 1948, many feared another civil war was on the horizon. The Liberal poor, however, felt they had one great hope for both a redress of grievances and peace in Gaitán (Bowden, 2001). Mance (2008) explains that Gaitán was at the center of the political fight in Bogotá. He had mobilized a massive popular following with passionate speeches denouncing the Colombian oligarchs and demanding social and economic reform; he was widely expected to win the upcoming presidential election.

However, as Colombian and foreign dignitaries met on April 9th, Gaitán did not have an official role to play, as his party was not in power. His only political engagement for the day seems to have been an afternoon meeting with a Cuban student by the name of Fidel Castro (Bowden, 2001). The meeting, however, would never happen. As he walked to lunch with some friends, a 26 year old schizophrenic walked up to Gaitán and fired multiple rounds into his torso at close range; he died quickly, and Colombia’s hope for peace died with him. Ironically, though Gaitán was a champion of peace in his life, he had frequently counseled his followers to pursue violent, revengeful path in the event of his assassination (Mance, 2008). They followed his orders.

Easterly (2015) contends that upon hearing of Gaitán’s death, enraged mobs of poverty-stricken liberals began looting, killing and raping all over Bogotá. Conservative mobs retaliated and the city devolved into anarchy. It took days before the army could end the Bogotazo and restore order (Easterly, 2015). The violence, however, quickly spread to the countryside and became a general civil war—known in Colombia as La Violencia—that lasted until 1956 and killed as many as 300,000 Colombians (Felbab-Brown, 2009). Easterly (2015) claims that the violence of this civil war was so gruesome that hangings and crucifixions became a common sight, prisoners were expelled from airplanes in flight, babies were bayoneted, children were raped en masse, and fetuses were removed by Caesarian sections and replaced with animals. Bruce et al. (2010) claim that burned, mutilated, decapitated corpses—mostly those of Liberal campesinos—became a regular sight across the nation. Much of this violence was perpetrated by government-sponsored Conservative death squads who targeted peasants of the Liberal Party in an effort to strengthen their hold on land and resources (“Colombia: La Violencia,” 2016). It was a nearly complete breakdown of the rule of law.

Bruce et al. (2010) explain that after the death of Gaitán and the Bogotazo, the Liberal Party abandoned the cause of the poor and returned to oligarchic interests; henceforth, the violence rarely affected the Liberal elite in the capital, and they turned a blind eye to the bloodshed in the countryside. Without support from their elite backers in Bogotá, elements of the Liberal poor—along with communist party members—fled to the hills to escape the death squads. Among those that escaped to Colombia’s Cordillera Central was a salesman named Pedro Marín, who had yet to reach the age of twenty. In the mountains, Marín took the nom de guerre Manuel Marulanda in honor of a murdered union leader and joined a guerrilla band focused on protecting the rights of poor farmers (Bruce et al., 2010). He quickly came to lead the group in their quest to form a society that was separate from the Colombian state (“Revolutionary Armed,” 2015). Marulanda later wrote of that period: “The police and armed conservatives would destroy the villages, kill inhabitants, burn their houses, take people prisoner and disappear them, steal livestock and rape women. The goal of the Conservative groups was to inflict terror on the population and take advantage of the goods the peasants had.” (Bruce et al., 2010, p. 22). Because of this violence, Marulanda and his followers spent the duration of La Violencia in their mountain hideouts forging a new society while protecting themselves from Conservative forces (Bruce et al., 2010).

According to Felbab-Brown (2009), nearly a decade of civil war did nothing to ameliorate the country’s profound socioeconomic and institutional problems that had led to this conflict in the first place:

…the concentration of land in the hands of the wealthy had increased, the peasants remained politically powerless, the same dominant classes retained control, and the exclusionary two-party political system was resuscitated under a power-sharing arrangement known as the Frente Nacional (National Front). (p. 77)

This political agreement, which ended La Violencia and lasted until 1974, left certain segments of Colombian society without non-violent means of political expression (Felbab-Brown, 2009). Though universal male suffrage was adopted in Colombia in the 1930’s, and universal female suffrage in the 1950’s, Schoultz (1972) contends that the plutocrats of the two main parties continued to monopolize power and largely prevent populist or dissident candidates from running for the presidency. This, combined with bureaucratic barriers to voting, resulted in very low voter turnouts and widespread apathy among Colombia’s voters in the middle third of the 20th Century (Schoultz, 1972). Even after the National Front officially ended in 1974, these established political parties continued to monopolize power through the widespread use of violence, largely preventing political outsiders from seeking power (Leech, 2011). The FARC was born from this exclusion and the continuing repression from government and Conservative forces (Holmes & Gutiérrez de Piñeres, 2014).

The FARC officially formed (first calling itself the Southern Bloc) in 1964 when the government attacked Marulanda’s band of Liberal and communist peasant fighters near Marquetalia (Leech, 2011). The group quickly declared themselves to be communists, and Marulanda—who by this point had over a decade of guerrilla experience—was made the chief leader, and the driver of military affairs (Bruce et al., 2010). As Marulanda was heavily influenced by the writings of Marx, Lenin, Mao, and Bolívar, it is not surprising that the FARC’s initial goal was to overthrow the Colombian state and seize control of the government (“Revolutionary Armed,” 2015). Once in power, the plan was to establish a socialist government, redistribute land to the poor, empower the peasants, and to develop the hinterlands in a socially just way (Felbab-Brown, 2009).

To achieve these goals, FARC leaders eventually embraced Mao’s strategy of Protracted Popular War (Ospina Ovalle, 2017b).[2] According to insurgency scholar Bard O’Neil (2005), this strategy has three phases—in the first phase, Strategic Defensive, insurgents must focus on political organization, low-level violence, and mere survival. Rabasa and Chalk (2001) state that the FARC used this strategy in the sixties and seventies, when they mostly conducted ambushes on Colombian military units and raids of farms. These tactics were used to obtain weapons, ammunition, food, and hostages. Simply continuing to exist as an organization was a difficult prospect for these insurgents at this time, as the Colombian army was determined to exterminate it and the group was very small.

Around 1979, the FARC finally gained enough resources and soldiers to worry about more than survival (Felbab-Brown, 2009). This initiated a transition to Mao’s second phase of Protracted Popular War, which occurred around 1982 after the 7th Guerrilla Conference (Ospina Ovalle, 2017b). This phase is termed Strategic Stalemate, and is characterized by guerrilla warfare, increasing numbers of followers, and sending agents into new regions to plant new cells (O’Neil, 2005). Profits from the drug trade, which the FARC embraced in 1982, greatly facilitated expansion during this stage (Felbab-Brown, 2009).

In Mao’s culminating phase—Strategic Offensive—guerilla tactics give way to mobile conventional warfare which is supposed to ultimately result in government capitulation (O’Neil, 2005). The FARC transitioned to this phase in August of 1996 when it initiated a night action in Las Delicias that resulted in a destroyed Colombian military base, fifty-four GoC personnel killed, and sixty captured (Marks, 2017; Rabasa & Chalk, 2001). In southern Caquetá two years later, a 600-800 strong FARC force surrounded and annihilated the elite 52nd counter-guerrilla battalion, killing 107 out of 154 soldiers (Rabasa & Chalk, 2001). The success of these and other operations lead the US Defense Intelligence Agency to sound the alarm in 1998; if the GoC did not radically transform its strategy, the FARC could defeat the military within five years (Leech, 2011). From 1964 to 1998, the FARC had grown from a small band of forty-eight peasant fighters to an insurgency that controlled forty percent of the national territory and boasted 18,000 fighters (Leech, 2011). This number of fighters may seem insignificant, given that Colombia had a population of over 38,000,000 people in 1998 (CIA World Fact Book 1998). It should be noted, however, that this number of fighters was probably close to the amount the FARC would have needed to defeat the Colombian government. This assertion is based on conclusions drawn from numerous studies that show counterinsurgents are rarely successful if they have less than a 10 to 1 advantage in manpower over insurgents (Woodford, 2016). At the time, the Colombian government had about 240,000 security personnel, but many of these were police, and all said forces were not engaged against the FARC (“United States,” 1999). The GoC would respond to the FARC’s growing power with a massive national effort that would ultimately force the FARC to agree to a negotiated settlement in 2016 (Ospina Ovalle, 2017a). Small and obscure at the beginning, none could know that this rag-tag organization would last for over fifty years, becoming one of the longest lasting insurgencies of all time. Nor could anyone know that the FARC would be one of the main players in a Colombian civil war that would result in roughly 220,000 killed, 25,000 disappeared, and 5.7 million displaced persons (Felter and Renwick, 2017). How was this insurgency able to persist for so long, despite a determined effort by the government to eradicate it?

The Failure of the Government to Cultivate Legitimacy With the Population

The FARC persisted for over fifty years because it was able to seize legitimacy from a Colombian state that largely failed to maintain its authority in the countryside right up to the early twenty-first century (Ospina Ovalle, 2017a). According to McDougall (2009), the Colombian government lacked the ability to extend its authority to the countryside for most of the state’s existence. This was largely the result of Colombian geography; three major Andean mountain ranges, vast swathes of jungle, and a subsequent poor road network isolated much of the country from the government in Bogotá (Leech, 2011). In practice, the real power in the countryside was the local landowner, whom the peasants labored for in a social relationship that has been termed partly feudal (Arjona, 2017). McDougall (2009) claims that this state weakness invited conflict because the government was unable to maintain its monopoly on the use of force. This left the population vulnerable to an assortment of dangers, including persecution by rich landowners, paramilitary groups, and narcotraffickers (Leech, 2011). This climate left rural Colombians in desperate need of government.

In fact, this lack of state protection resulted in the abrogation of the state’s social contract with, and what Nuñez (2001) deems a Hobbesian existence for, much of the rural population. According to Thomas Hobbes (1651/1909), rational humans choose to submit to Leviathan, or the state, because the state protects them from the State of Nature. The State of Nature is a hypothetical representation of a world in which there are no laws and all people compete with each other in a violent and anarchic competition for resources. Hobbes describes this existence as follows:

Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time or war where every man is enemy to every man, the same is consequent to the time wherein men live without other security than what their own strength and their own invention shall furnish them withal. In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently no culture of the earth, no navigation nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea, no commodious building, no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force, no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and, which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. (Part I, Chapter VIII)

Thus, according to Hobbes (1651/1909) citizens surrender some of their freedom to the state in a social contract because, if they do not, their lives will be filled with violence and insecurity. This is representative of the conditions experienced by most of the initial members of the FARC before, during, and immediately after La Violencia, when violent actors rampaged through the countryside with impunity (Bruce et al., 2010). Just as Hobbes predicted, this violence and insecurity made it nearly impossible for these citizens to engage in commerce and industry, or to enjoy the pleasures of life (Leech, 2011). This insecurity created a situation that invited the rise of the FARC. This is because the security that government provides is so valuable that, “If people can’t get the leadership they crave from the state, they’ll find somebody else to do the job” (Hamid, Felbab-Brown, and Trinkunas, 2018, pg. 69).

The FARC responded to these conditions by establishing “law and order in areas under their control” (Felbab Brown, 2009, p. 80). According to Gary Leech (2011), the FARC acted like a state in many of these areas. They taxed the population and protected the people from other armed groups in return. The FARC also funneled profits from its taxation schemes into a multitude of social projects and infrastructure improvements in these areas. The group built hundreds of miles of roads to connect rural communities, erected massive bridges that spanned mountain chasms, and even established electrical grids. The insurgents also established a judicial system that provided citizens with an avenue to mediate disputes other than violence. Furthermore, the insurgents increased education, health, and ecological services. In effect, the FARC gained legitimacy with the people as the de-facto government in much of the Colombian countryside. It should also be noted that the GoC made matters worse in this regard by allowing and colluding with right-wing militias that attacked the populous with impunity, further driving the citizenry into the arms of the FARC for protection (Leech, 2011).[3] The FARC persisted for so long because the GoC failed to address this legitimacy issue until the insurgency was nearly forty years old (Ospina Ovalle, 2017a). Instead of addressing this root-cause of the FARC insurgency, the Colombian state spent most of the 1980s and 1990s with its efforts focused on one of its symptoms: narcotics (Felbab-Brown, 2009).

Misidentification of the Center of Gravity in the Conflict

General Carlos Alberto Ospina Ovalle (2017a), who spent years fighting the FARC and commanded Colombia’s armed forces from 2004-2007, believes that the group persisted for so long because the government failed to properly identify and attack the FARC’s center of gravity. According to Carl von Clausewitz, an armed group’s Center of Gravity (CoG) is, “…the hub of all power and movement, on which everything depends. That is the point against which all…energies should be directed (as cited in Burgoyne, 2012).” Clausewitz further describes CoG as, “…the source of power that provides moral or physical strength, freedom of action, or will to act” (as cited in Ospina Ovalle, 2017a, p.256). In order for an adversary to be defeated, their CoG must be correctly identified and destroyed.

Since it embraced the drug economy in 1982, the FARC’s enemies increasingly saw or wanted to paint it as an organization that was motivated and sustained by profit, not ideology (Leech, 2011). This caused the Colombian armed forces to incorrectly identify the FARC’s CoG as drug trafficking revenues for decades (Ospina Ovalle, 2017a). Those ascribing to this belief would contend that the FARC persisted for so long because the group derived so much wealth from its drug-related activities. Luis Alberto Moreno, a former Colombian Ambassador to the United States, put it this way: “Drugs are the root of almost all violence in Colombia […] While they may hide behind a Marxist ideology, Colombia’s leftist guerrillas have ceased to be a political insurgency. They have traded their ideals for drug profits.” (as cited in Felbab-Brown, 2009). Felbab-Brown (2009) asserts that this belief resulted in over thirty years of a drug-eradication based counterinsurgency strategy, which culminated in Plan Colombia—the most intensive aerial eradication campaign in history. This strategy was flawed and failed to seriously weaken the FARC (Felbab-Brown, 2009). In fact, this narcotics-based strategy may have done more harm than good.

In pursuing this strategy, the GoC failed to recognize that rural farmers were growing coca and other illicit crops because the government had not provided them with the requisite infrastructure to transport licit crops to market (Leech, 2011). Thus, according to Felbab-Brown (2009), the aerial spraying campaign sparked widespread resentment of the government, while simultaneously increasing support for the FARC in rural areas. The FARC capitalized further on this eradication campaign by protecting farmers from the spray planes, while simultaneously launching a very effective propaganda effort that highlighted the dangers of spraying aerial herbicides. This is why over thirty years of attacking drugs did not defeat the organization, and why the group continued to control up to 60% of the country’s coca production up through 2013 (Felbab-Brown, 2009; Otis, 2014). Drugs, therefore, were wrongly identified as the center of gravity in the conflict against the FARC.

This argument may be difficult for critics to accept, given the fact that the $60-$100 million the FARC earned annually from the drug trade allowed the insurgents to greatly enhance their military arsenal while expanding from nine fronts in 1979 to sixty fronts in 1995 (Felbab-Brown, 2009). Distinguished Colombian sociologist Alfredo Molano (as cited in Leech, 2011) however, provides a convincing counterpoint to said critics by arguing that the FARC’s growth during this period was due largely to government repression of the people, and continued economic hardships:

The guerrillas’ rapprochement with coca also led to the belief that they are traffickers—narcoguerrillas. That notion is false, however. Cultivation of illegal crops was established…not simply because of weak army presence, but because the … [peasants] … were on the brink of ruin … the [FARC] guerrillas were in the colonized regions long before coca cultivation appeared. Their growth was due mainly to the repression…and by the growing impoverishment of the population—not their participation in the drug trade. (p. 63)

The “repression” mentioned by Molano here is a reference to the human rights abuses committed by paramilitary groups that colluded widely with the GoC in its war on the FARC (Leech, 2011). These paramilitaries committed the vast majority of human rights abuses in the country from the mid-1980s onward, habitually massacring campesinos under the slightest suspicion of colluding with the guerrillas (Leech, 2011). The plight of the campesinos living in this security environment was further troubled by increasing economic hardships. As the civil war dragged on, paramilitary groups often colluded with big agri-businesses to clear farmers off of their land (Fox, 2012). This is partly why land was further concentrated in the hands of the ultra-wealthy during the fifty plus years of the FARC insurgency (Gillin, 2015).

Therefore, the continued impoverishment of the Colombian people and state repression—both of which cost the state legitimacy—are the real reasons for the FARC’s success. The FARC in fact had been operating as an official insurgent group eighteen years before they embraced the drug trade in 1982, and FARC members had been operating as guerrillas in Liberal groups since La Violencia (Felbab-Brown, 2009). The drug trade may have greatly enhanced the FARC’s capabilities, but narcotics profits were not their center of gravity and attacking the narcotics trade was a wasted effort.

Seizing Legitimacy from the FARC

Though the war on the coca leaf in Colombia appears to have been a wasted effort, a few reforms were made in that era that would serve as a foundation for the strategy that would ultimately end the FARC’s persistence. The first major change was the implementation of the Colombian Constitution of 1991. According to Spencer (2012), this constitution was designed to end the dominance of the Liberal and Conservative parties, decentralize government, establish checks on the executive branch, and provide more rights to citizens. The next major reforms were the overhauling of the police in 1992 and the military in 1997. These “overhauls winnowed out many elements suspected of misbehavior or incompetence, while reorganizing and reequipping the armed forces to face the threats more effectively” (Spencer, 2012, p. 11-12). These reforms made it possible for the GoC’s new strategy to succeed in the 2000s.

According to General Ospina Ovalle (2017a), once the GoC (in the early 2000s) realized that legitimacy—not drugs—was the center of gravity in the conflict, the FARC lost the initiative and was subsequently defeated:

we decided to consider legitimacy as our CoG […] This changed the whole situation of our war and contributed to the defeat of the FARC […] in many Colombian provinces, we considered local security issues, low local economic production and poor people’s welfare as overlapping problems […] Without local security, legitimacy collapses since nothing can be achieved. Moreover, we can say that the value of local security is a priority to the strength of state legitimacy. Therefore, if you have strong local security, you will have strong legitimacy. Furthermore, you have to consider local security as one of the two basic elements since local economy is also essential. When both elements come together, they provide trust in the State. This trust prevents any popular mobilization in favour of the insurgency due to the acceptance of government policies and the rise of confidence in them among the peasantry. (p. 256-257)

This strategy emphasized local security, social programs for rural communities, and trust building—once the people trusted the government to provide security and support, support for the guerrillas began to evaporate (Ospina Ovalle, 2017a). Though not mentioned by Ospina Ovalle, the demobilization of the major paramilitary group, the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) in 2006 undoubtedly helped the GoC seize legitimacy from the FARC. This is because the existence of these illegal paramilitaries hurt the government’s legitimacy by making the government appear weak (Spencer, 2012).

According to Thomas Marks (2017), the FARC also helped this process along with its decision to increasingly rely on criminality to support its insurgency. This is due to the fact that the targets of the FARC’s extortion, kidnapping, and terrorist attacks were the people themselves. Therefore, when the GoC adopted this new strategy, many citizens in FARC-controlled areas readily shifted their allegiance from the FARC to the state (Marks, 2017). About eleven years after the Colombian military adopted this approach, the FARC had been eroded enough to force its negotiated capitulation (“Revolutionary Armed,” 2015).

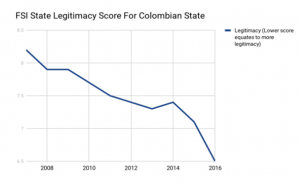

The following charts, though they do not provide direct causal evidence, provide further support for this argument. Chart 1 depicts data from the Fragile States Index (FSI). The FSI Legitimacy “Indicator looks at the population’s level of confidence in state institutions and processes, and assesses the effects where that confidence is absent, manifested through mass public demonstrations, sustained civil disobedience, or the rise of armed insurgencies (Fragile States Index, 2018). This chart depicts the legitimacy of the Colombian state in the ten years preceding the signing of the FARC peace deal. It is important to note that the lower the score on this chart, the more legitimacy the state has. It can therefore be inferred from the data that the Colombian government’s legitimacy increased drastically in the ten years preceding the capitulation of the FARC.

Chart 1

Source: Fund For Peace Fragile States Index Data

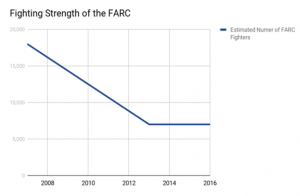

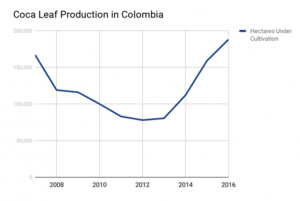

While we do not have data that directly measure the FARC’s legitimacy during the time period in question, we can observe that the group experienced a massive loss of fighters (“Revolutionary Armed,” 2015; Daly, 2017). While some of these losses can certainly be attributed to combat deaths, it is probable that the vast majority were due to desertions (McDermott, 2008). Thus, there appears to be a negative correlation between the legitimacy of the state and the FARC’s fighting strength. This lends credence to the belief that the FARC’s persistence was due to the state’s lack of legitimacy. Chart 3 shows coca leaf production in Colombia during the same time period in question. The data shows that coca production increased dramatically just as the FARC was dwindling in strength. While the coca production data encompasses all production in Colombia, not just that of the FARC, it can be generally inferred that if the persistence of the FARC was due to drug revenues, the organization should have thrived during this period. Instead, the insurgents sued for peace.

Chart 2

Source: Mapping Militant Organizations and the Washington Post

Chart 3

Source: U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency

Ideological Commitment of the FARC

The FARC’s enduring ideological commitment also contributed to its persistence. While some elements of the FARC did become distracted and corrupted by the drug trade, its core leaders and members remained highly ideological and committed to socialism throughout the insurgency (Leech, 2011). Many of the FARC’s critics have downplayed the egalitarian nature of the insurgency in an attempt to cast it in the less-sympathetic light of a commercialist insurgency focused on narcotics profits (Felbab-Brown, 2009). In this type of insurgency, the “main aim appears to be nothing more than the acquisition of material resources through seizure and control of political power” (O’Neil, 2005, p. 28). Though the FARC did embrace the narco-economy in 1982 as a way to fund operations, Leech (2011) argues that the group remained highly ideological and committed to egalitarianism throughout its existence. To highlight this point, Leech points out that while the narco and paramilitary leaders were utilizing narcotics revenues to live lavish lifestyles in mansions and on massive ranches, the principle FARC leaders were sleeping on wooden beds in the jungle with their troops. In fact, Marulanda spent almost fifty years with his soldiers in the jungle; bathing in freezing rivers, fighting off tropical diseases, and constantly moving camp. His decision—and that of other FARC leaders—to reject a life of luxury when they could easily have had it shows that they were motivated by something other than money. To further highlight this point it is worth noting that even after fifty years of hostilities, the FARC conducted regular political training in Marxism for its fighters and that captured FARC computers nearly always contained two of Mao’s works—On Protracted War and Problems of Strategy in Guerrilla War against Japan (Gentry & Spencer, 2010; Leech, 2011).

The Absence of Safety Guarantees

According to Barbara Walters (1997), ending civil conflict through negotiation is especially difficult because combatants take the risk that they will be wiped out after they demobilize. This places a group like the FARC in a prisoner’s dilemma; they stand to benefit from negotiated settlement, but the risk outweighs the potential reward (Walters, 1997). According to Leech (2011), the Colombian state undertook two actions that caused FARC leaders to believe that they would be annihilated if they demobilized. First, During La Violencia, Conservative President Gustavo Rojas Pinilla offered amnesty to armed Liberal peasants in an attempt to end the conflict. Many accepted his offer and were subsequently killed by the military after they laid down their arms. Second, during a round of peace negotiations in the 80s, the FARC established the Patriotic Union (UP) Party in an effort to achieve its goals through the democratic process. Paramilitaries (with no resistance from the state) ultimately killed thousands of UP members in systematic killings around the country in an effort to curb leftist political thought. These two incidents caused the FARC to believe that negotiation was not a viable option (Leech, 2011). Furthermore, this lack of trust threatens to undermine the implementation of the current peace agreement. According to June Beittel (2017) as of October 2017, nearly twenty-four ex-FARC fighters (including some family members) have reportedly been killed. In early 2018, prominent FARC negotiator Seuxis Hernández was arrested and informed that he is facing extradition to the US on drug charges—the peace agreement states clearly that FARC members will not be charged or extradited for past crimes (Feingold, 2018). Though Hernández very well may have committed these new crimes, this event could serve to further break down the peace agreement.

Conclusion

Ultimately, a band of forty eight slightly educated campesinos was able to build a shadow government that governed forty percent of Colombia’s national territory (Leech, 2011). The FARC was able to organize, survive initial government onslaughts, train and recruit soldiers, and fund operations because of the absence of the state from much of the Colombian countryside. The absence of the state equated to the abrogation of its social contract with the Colombian people, as evidenced by the insecurity of the rural populous. The FARC’s ability to restore the social contract in its traditional strongholds garnered it the support and admiration of the local population (Leech, 2011). It gave the group legitimacy. This legitimacy with the people is the primary reason the FARC was able to persist for so long. The proof of this thesis lies in what ultimately caused the group’s downfall; when the state implemented a plan to seize legitimacy from the FARC, the group dwindled and ultimately sued for peace. Though the FARC did largely demobilize, it is also important to remember that the group continues to persist as a political party and that perhaps five to ten percent of the organization’s fighters failed to demobilize (Beittel, 2017). If the government fails to consolidate its gains in legitimacy, or if it reneges on its agreement with the FARC, the organization could very well return to arms, or its fighters will simply join emerging criminal groups in Colombia.

References

Arjona, A. (2017). Rebelocracy: Social Order In the Colombian Civil War. Cambridge; New York; Melbourne; Delhi; Singapore: Cambridge University Press.

Beittel, J. S. (2017). Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations. Congressional Research Service.

Borch, G. W., & Stuvoy, K. (2008). Practices of Self-Legitimation in Armed Groups: Money and Mystique of the FARC in Colombia. Distinktion: Scandinavian Journal Of Social Theory, 9(2), 97-120.

Bowden, M. (2001). Killing Pablo: The Hunt For The World’s Greatest Outlaw. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

Bruce, V., Hayes, K., & Botero, J. E. (2010). Hostage Nation: Colombia’s Guerrilla Army and the Failed War On Drugs. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Burgoyne, M. (2012). Breaking Illicit Rice Bowls: A Framework for Analyzing Criminal National Security Threats. Small Wars Journal. Retrieved from http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/breaking-illicit-rice-bowls-a-framework-for-analyzing-criminal-national-security-threats.

CIA World Fact Book. (1998). Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/theciaworldfactb02016gut/pg2016.txt

Colombia: La Violencia. (2016, December 14). Retrieved from https://sites.tufts.edu/atrocityendings/2016/12/14/colombia-la-violencia-2/.

Daly, S. Z. (2017, April 21). Analysis | 7,000 FARC rebels are demobilizing in Colombia. But where do they go next? The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/04/21/7000-farc-rebels-are-demobilizing-in-colombia-but-where-do-they-go-next/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.02036330b4b0.

Easterly, W. (2015). The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor. New York: Basic Books, a member of the Perseus Book Group.

Felbab-Brown, V. (2009). Shooting Up: Counterinsurgency and the War on Drugs. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Feingold, S. (2018, April 10). Colombia arrests negotiator in FARC peace deal on drug trafficking charge. CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2018/04/10/americas/colombia-farc-santrich-arrest/index.html.

Felter, C., & Renwick, D. (2017, January 11). Colombia’s Civil Conflict. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/colombias-civil-conflict.

Fox, E. (2012, August 08). Colombia’s Anti-Land Restitution Army. InSight Crime. Retrieved from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/colombias-anti-land-restitution-army/.

Fragile States Index Data on Colombia. (n.d.). Fund For Peace. Retrieved April 16, 2018, from http://fundforpeace.org/fsi/country-data/.

Gentry, J. A., & Spencer, D. E. (2010). Colombia’s FARC: A Portrait of Insurgent Intelligence. Intelligence & National Security, 25(4), 453-478. doi:10.1080/02684527.2010.537024.

Gillin, J. (2015, January 7). Understanding Colombia’s Conflict: Inequality. Colombia Reports. Retrieved from https://colombiareports.com/understanding-colombias-conflict-inequality/.

Hamid, S., Felbab-Brown, V., & Trinkunas, H. (2018, April 4). When Terrorists and Criminals Govern Better Than Governments. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/04/terrorism-governance-religion/556817/.

Hobbes, T. (1651/1909). Leviathan. The Harvard Classics. New York: P.F. Collier & Son. Bartleby.com. Retrieved from www.bartleby.com/34/5/.

Holmes, J. S., & Amin Gutiérrez de Piñeres, S. (2014). Violence and the state: Lessons from Colombia. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 25(2), 372-403. doi:10.1080/09592318.2013.857939.

Leech, G. (2011). The FARC: The Longest Insurgency. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

Mance, H. (2008, April 09). Colombia Marks a Deadly Date. BBC News. Retrieved April 08, 2018, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/7334165.stm.

Marks, Thomas A. 2017. FARC, 1982-2002: criminal foundation for insurgent defeat. Small Wars & Insurgencies 28, no. 3: 488-523.

McDermott, J. (2008, November 30). Mass desertions from FARC as Colombia government seeks to end conflict. The Telegraph. Retrieved April 16, 2018, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/southamerica/colombia/3537081/Mass-desertions-from-FARC-as-Colombia-government-seeks-to-end-conflict.html.

McDougall, A. (2009). State Power and Its Implications for Civil War Colombia. Studies In Conflict & Terrorism, 32(4), 322-345. doi:10.1080/10576100902743815.

Nuñez, J. R. (2001, April). FIGHTING THE HOBBESIAN TRINITY IN COLOMBIA: A NEW STRATEGY FOR PEACE. Strategic Studies Institute. Retrieved from http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pdffiles/pub28.pdf.

O’Neill, B. (2005). Insurgency & Terrorism: From Revolution To Apocalypse. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books.

Ospina Ovalle, G. (2017a). Legitimacy as the center of gravity in Hybrid warfare: Notes from the Colombian Battlefield. Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 17(4). Retrieved from http://jmss.org/jmss/index.php/jmss/article/view/709.

Ospina Ovalle, C. A. (2017b). Was FARC militarily defeated?. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 28 (3), 524-545. doi:10.1080/09592318.2017.1307613.

Otis, J. (2014, November). The FARC and Colombia’s Illegal Drug Trade. Wilson Center. Retrieved from https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/Otis_FARCDrugTrade2014.pdf.

Rabasa, A., & Chalk, P. (2001) Colombian labyrinth: the synergy of drugs and insurgency and its implications for regional stability. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1339/MR1339.ch3.pdf.

Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army. (2015). Mapping Militant Organizations at Stanford University. Retrieved April 09, 2018, from http://web.stanford.edu/group/mappingmilitants/cgi-bin/groups/view/89.

Schoultz, L. (1972). Urbanization and Changing Voting Patterns: Colombia, 1946-1970. Political Science Quarterly, 87(1), 22-45. doi:10.2307/2147776.

Sioneriu, L. (2018, April 01). Profile of Jorge Eliecer Gaitan. Colombia Reports. Retrieved from https://colombiareports.com/jorge-eliece-gaitan/.

Spencer, D. (2012, May). Lessons From Colombia’s Road to Recovery, 1982-2010. National Defense University. Retrieved from https://www.williamjperrycenter.org/content/lessons-colombia’s-road-recovery-1982-201.

Walters, B. (1997). The Critical Barrier to Civil War Settlement. (cover story). International Organization, 51(3), 336-364.

Woodford, S. R. (2016). Manpower and Counterinsurgency. Small Wars Journal. Retrieved May 2, 2018, from http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/manpower-and-counterinsurgency.

Footnotes

[1] The group was called the Southern Bloc from 1964-1966. In 1966 it changed its name to the FARC. In 1982, it changed its name to the FARC-EP, adding Ejercito del Pueblo (Army of the People) on to its name. For convenience, I will simply refer to the group as the FARC throughout this paper.

[2] It should be noted that the FARC’s strategy is difficult to classify. Scholars such as Putsay (1977), O’Neil (2005), Gentry & Spencer (2010), Leech (2011), and Ospina Ovalle (2017a) all have slightly different interpretations of said strategy. This is probably because the FARC eventually controlled 40% of Colombia and its strategy tended to vary depending on local conditions (Leech, 2011). All of these interpretations, however, are variants of, or closely related to Mao’s protracted popular war, which the FARC did loosely follow (O’Neil, 2005). In breaking the FARC’s chronological history into the phases of Mao’s protracted popular war in this section, I have highlighted what the FARC’s general strategy was in practice (according to the above authors) at different times during the insurgency.

[3] It should be noted that the FARC did not establish this level of governance in all of its fronts. Leech (2011) notes that some regions did not experience this level of political involvement. However, the core historical FARC regions did.

Written by: Bryan T. Baker

Written at: The University of Arizona

Written for: Independent Study

Date written: May 2018

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- To What Extent Can History Be Used to Predict the Future in Colombia?

- Double Agency? On the Role of LTTE and FARC Female Fighters in War and Peace

- Liberal Peacebuilding and the Road to Hybrid Emancipatory Peace in Colombia

- Transitional Justice in Colombia: Between Retributive and Restorative Justice

- Deconstructing Narco-Terrorism in Failed States: Afghanistan and Colombia

- Colombia and Chile: How Parties and Ideologies Affect LGBTQ+ Identities