This is an excerpt from Critical Perspectives on Migration in the Twenty-First Century. Download your free copy here.

Since the outbreak of the Syrian conflict in 2011, nearly five million refugees settled in neighbouring countries. This massive refugee movement follows others, such as the forced exile of Palestinians after the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, Lebanese from 1975 to 1990 or Iraqis since the early 1980s (Chatty 2010). Refugee movements are one of the major consequences of the political crises in the Middle East in recent decades. As a result, the region is hosting one of the largest refugee populations in the world, while most of the host countries (except Turkey and Israel with time and geographical restrictions) are not signatories of the Geneva Convention of 1951. In consequence there is no specific asylum legislation in these host countries (Kagan 2011). The region is also characterised by strong and ancient human mobility as a result of regional economic disparities and transnational social ties (Marfleet 2007). Today’s forced migration movements appear to be linked with previous cross border migration at a regional level. Current geographical distribution of Syrian refugees is partially shaped by pre-existing ties and regional labour migration. This chapter will focus first on the socio-political consequences of the mass arrival of Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan. It will focus more specifically on the gradual changes of migration policies in both countries and their consequences on migration patterns. Special attention will be placed on Palestinian refugees from Syria, who face double displacement. It will then analyse the forms of settlement of Syrian refugees in both countries, with a focus on Jordan. The Syrian crisis has led to a shift in the Jordanian settlement policy. Until 2012, when Zaatari camp opened in Northern Jordan, the reluctance of the authorities of the host countries to open new camps was based on the fear of permanent settlement of refugees on their territory, as is the case for Palestinians.

Conflict, Migration and the Syrian Crisis in the Middle East

The current Syrian forced migration movement has produced deep changes in the Middle East migration system. Before 2011, Syria was hosting large numbers of refugees, comprised mainly of Palestinians and Iraqis but also Sudanese and Somalis (Doraï 2011). Meanwhile hundreds of thousands of Syrian labour migrants were working in Lebanon and in the Gulf countries (Shah 2004). Since the outbreak of the conflict in 2011, Syria is one of the main countries of origin of refugees in the world, with more than five million Syrians fleeing their home, mostly to neighbouring countries. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq are currently hosting the vast majority of the Syrian refugees.

A Massive Refugee Movement Concentrated in Neighbouring Countries

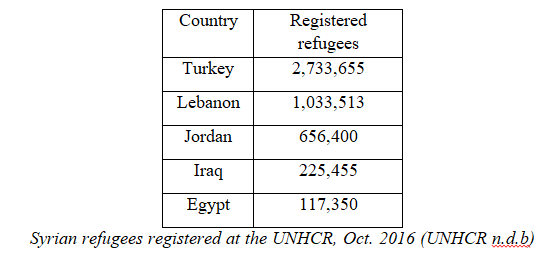

The high concentration of Syrian refugees in the Middle East can be partly explained by the historical and previous migratory links existing between the countries in the region. Bilateral agreements existed to facilitate the circulation and employment – with restrictions – of people. Regional mobility pre-existed the independence of states in the region. When national borders were created at the beginning of the twentieth century, this circular migration transformed into transnational networks. The settlement of Syrian refugees is also the result of an open door policy during the first two years of the conflict. The Middle East is not an exception as most of the refugees in the world find asylum in neighbouring countries (UNHCR 2016, 15). The settlement of these refugees is also linked to the development of increasingly restrictive migration policies by most of the European countries, with the exception of Germany and Sweden. These two countries have received 64% of the total asylum applications in Europe (UNHCR n.d.a).Syrian refugees registered at the UNHCR, Oct. 2016 (UNHCR n.d.b)

The recent agreement between Turkey and the European Union aims to stabilise Syrian refugees outside EU territory (Krumm 2015). European Union countries try to limit new entries, while the causes of departures are not addressed effectively both for those who continue to leave Syria or their country of first asylum (Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq). Some new agreements are being implemented in neighbouring countries. For example, since April 2016, Jordan has adopted a new regulation to give Syrian workers access to the labour market, but it still concerns a limited number of refugees (according to the Jordan Ministry of Labour, 37,000 Syrian workers had obtained a work permit by the end of 2016). The permanence of conflict is always a determining factor that leads to more departures. Meanwhile, the condition of exile in neighbouring countries leads to increasing impoverishment of the poorest refugees who have limited access to the legal labour market and resources. The Syrians are mostly confined to the informal sector and very exposed to competition with other migrant groups, such as Egyptian workers. Their precarious legal status is also a source of instability. The combination of all these factors explains the continuing migration to Europe.

From Cross-Border Circulation to Restrictive Migration Policies

The current Syrian refugee movement cannot be understood without taking into consideration the history of cross-border mobility in the region. Before 2011, migratory circulation was sustained by the existence of well-established transnational networks. Circulation from Syria towards Lebanon or Jordan had different purposes: family visits, marriage or commercial activities. If the presence of Syrians is well documented in Lebanon (Chalcraft 2009; Longuenesse 2015), the current Syrian crisis has shed light on the growing presence of Syrians in Jordan (Al Khouri 2004). Historical links existed between Southern Syria and Northern Jordan – especially tribal and family links – even if it is difficult to evaluate their number before 2011. There was also a group of Syrians who found asylum in Jordan in 1982 after the Hama massacre. Some of them settled permanently in Jordan and opened businesses. They are well integrated in the Jordanian society and participate actively in the private sector.[1]

Migration policies of neighbouring states have dramatically changed since 2011. Syrians were enjoying relative freedom of cross-border mobility towards Lebanon and Jordan. They also had access – with some restrictions in both countries – to the labour market. Both countries had signed agreements with the Syrian government to facilitate the circulation of migrant workers. Due to the mass arrival of Syrians after 2011 and the fear of their permanent settlement in the country, Lebanon suspended a bilateral agreement in 2014 – originally implemented in 1994 – on the access of Syrians to the labour market (Longuenesse 2015). At the same time, refugees were still arriving en masse in the country, trying to find jobs. If the conflict in Syria has led to the forced migration of hundreds of thousands of refugees, economic migration did not disappear. Nearly 400,000 Syrians were working in Lebanon before 2011 (Chalcraft 2009). Most of them became de facto forced migrants, as they could not go back home. A large portion of them registered with the UNHCR (Knudsen 2017). Jordan has also gradually implemented restrictive entry policies for Syrians (Ababsa 2015). The opening of the Zaatari refugee camp in July 2012 can be considered a first turning point to regulate entries of Syrian refugees. Then more restrictions were imposed. Today, even if the border is still officially open, very few Syrian refugees are allowed to enter. The main consequence is that the camp of Rukban on the eastern part of the border transformed from a transit place into a camp. It now hosts more than 85,000 Syrian refugees in a no man’s land between the two countries with very limited access to humanitarian assistance (UNHCR 2017).

One important element to take into consideration is that there is no clear distinction between migration policy and asylum policy in Lebanon and Jordan. Like other countries in the region, they are not signatories of the Geneva Convention of 1951 on refugees (Zaiotti 2006). Only Palestinians are recognised as refugees in the state where they have their permanent residency when they are registered with United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Thus, both countries have no national asylum system. It is the UNHCR that establishes asylum procedures in cooperation with host governments. Lebanon and Jordan have signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the UNHCR that specifies the mandate of the international organisation (Kagan 2011, 9), from which Palestinians (covered by another international organisation, UNRWA) are excluded.

Palestinians and Iraqis: From Refugees in Syria to Asylum Seekers?

The massive forced migration of Syrians should not conceal the fact that other refugee groups who were residing in Syria have also been forced to escape war and violence. UNRWA estimated the total number of Palestinian refugees displaced inside Syria at just over 250,000 (half of the total number registered in Syria), a large portion originating from Yarmouk camp in Damascus. More than 70,000 of them were forced to seek asylum in neighbouring countries mainly to Lebanon (50,000), Jordan (6,000) and Egypt (9,000) (UNRWA n.d.). Those who are still in Syria, reside in safer places than their habitual place of residency (some camps, like Yarmouk in Damascus or Handarat close to Aleppo have been subject to heavy destruction and blockade). Eight thousand refugees whose homes were destroyed live in UNRWA facilities, generally in schools. Some Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) were able to return to their homes, but the number of new refugees that moved en masse remains higher.

The current conflict has had dramatic consequences for the Palestinian population in Syria. Palestinians were enjoying access to education and the labour market without particular discrimination in Syria before 2011 (Shiblak 1996). The outbreak of the Syrian conflict in 2011 consigned Palestinians to their stateless status. All this seems to replicate a scenario already seen with Palestinians from Iraq in the aftermath of the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003 (Doraï and Al Husseini 2013). Palestinian refugees are not covered by the UNHCR mandate, as they already receive assistance from the UNRWA (Feldman 2012). They lack legal protection transforming them de facto into illegal migrants subject to potential deportation towards Syria. Palestinian refugees tend to be transformed into asylum seekers by conflicts. Jordan quickly decided to close its doors to this category of refugees, limiting drastically their possibility to escape violence from Syria. As written by Jalal Al Husseini (2015),

after a relatively tolerant phase during which some 10,000 Palestinian refugees have been able to enter the country, Jordan has tightened its entry policy since late 2012 on behalf of the need to counter the Israeli vision of Jordan as Palestinian homeland of substitution.

Lebanon, until 2013, had adopted a more flexible policy, and hosted more than 75% of the Palestinian refugees from Syria. For the same reasons, Lebanon also decided in 2014 to close its borders for them (Doraï 2015).

The absence of a legal framework concerning Palestinian refugees, who are forced to leave their country of residence as well as the political treatment of the Palestinian refugees by states in the region, raises the problem of secondary migration during conflict. Refugees already residing in Syria (mainly Iraqis and Palestinians) face several limitations to their mobility and protection. Because Middle Eastern countries are not signatories of the 1951 Geneva Convention, they lack protection when they escape a conflict for a second time.

Today, other refugees, such as Iraqis who were in Syria before 2011, can face similar problems. Iraqi refugees who sought refuge in Syria, mostly in the suburbs of Damascus (Doraï 2014), have also been forced to leave their countries of first asylum. The majority returned to Iraq, despite continuing violence. Others were able to continue their journey to Europe, North America or Australia. According to UNHCR, around 20,000 are still in Syria because they cannot leave the country. These populations, already refugees before the Syrian conflict, find themselves therefore forced to new mobility in a context where Syrian neighbouring countries are reluctant to give them asylum. Not being part of the 1951 Geneva Convention, they do not want to be considered resettlement countries. As most of these refugees are unable to move, even temporarily, in the Middle East, a growing number of them are seeking more sustainable solutions outside the region. Jordan and Lebanon consider themselves as only temporary host countries and develop policies that incite refugees to immigrate to third countries to settle permanently and access a new citizenship (Chatelard 2002).

From Exile to Temporary Settlement: Refugees in Camps and Urban Refugees

The Syrian crisis has reopened the debate in the region on the creation of new refugee camps. While Middle Eastern states chose not to open refugee camps during the last Iraqi crisis in 2003[2], Jordan and Turkey took a different decision after 2011 (Achilli et al. 2017). In Lebanon, no official camps have been opened. As a result, a myriad of unofficial refugee camps of small sizes mushroomed, where refugees are especially vulnerable due to lack of coordination of assistance. Most of the current Syrian refugee population settle in urban areas or already existing villages to access resources and develop their own social and economic activities in certain localities, thereby contributing to urban change and development.

The Palestinian Experience and Its Current Consequences

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, host states in the Middle East are reluctant to open new refugee camps. The Iraq wars of 1990–1991 and post-2003 demonstrated for Jordan, Syria and Lebanon that the absence of camps, combined with a relative freedom of entry and residence at the beginning of the crises and a fairly easy access to public services and employment in the informal labour market, have increased the possibility of mobility of refugees and therefore their re-emigration to third countries (Chatelard and Doraï 2009). Additionally, the decision not to open refugee camps is the result of both state policies that try to avoid the creation of camps, and the refugees’ very own reasoning. Most of the refugees prefer to settle in urban settings or in agricultural areas where they can find employment.

Lebanon, where the Palestinian presence – and therefore the camps – is marked by a history of conflict (Sayigh 1991) and a complex relationship with Palestinian refugees prevails, has so far refused to officially open camps for Syrians on its territory. The fear of creating ‘Syrian’ spaces in Lebanon, which could lead to the development of political and/or armed movements, remains strong for the Lebanese political leaders. Political parties are also deeply divided on the Syrian conflict. Some pro-regime groups not belonging to the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) or Hamas, such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command (PFLP-CG), support the Assad regime while others, through the creation of ‘organizational committees’[3], support Syrian opposition groups (Napolitano 2012).

In Jordan, the camp of Azraq, built to accommodate 130,000 people when the number of arrivals of refugees was very high, is now largely empty. The UNHCR has registered almost 55,000 refugees in August 2016, half of Azraq’s capacity. Most of the Syrian refugees, when they have the possibility, prefer to settle in urban areas where the opportunities of finding a job are higher and where rebuilding a ‘normal’ life is easier.

Unlike Lebanon, that hosts more refugees, Jordan opened refugee camps in the north of the country to control the flow of new arrivals. Turkey has also opened camps along its border with Syria. Nevertheless, at a regional scale, still less than 20% of the refugees live in camps. Most of the refugees prefer to settle outside camps to integrate into the local economy and develop links with the host societies, while refugee camps recently created cannot accommodate such a large number of refugees. Jordan opened three main camps. Most of the refugees transited through Zaatari, and to a lesser extent Azraq camps. Transit camps (Ruqban and Hadalat) have been opened on the border between Syria and Jordan parallel to the gradual closure of the border. These transit camps have been created to enable Jordanian authorities to make safety checks before allowing refugees to enter their territory. The waiting time in these camps varies with profiles of the refugees. Those who come from territories controlled by Daesh[4] have to go through a long security procedure, especially young men without family. Until the spring of 2016, most of the refugees spent only a few days in these camps before being accepted or rejected. Since then, and following an attack on Jordanian border guards in June 2013, only a very limited number of refugees were allowed to enter through the camp of Ruqban. Once accepted, they are then directed to one of three settlement camps. If they have a Jordanian kafil (sponsor) they can move and settle elsewhere in the country.

The Urban Integration of Syrian Refugees

Despite current conflicts, refugee movements in the region are generally long lasting (the Palestinian refugee problem started in 1948 and the Iraqi one in the early 1980s), and the end of conflict does not always mean return for the entire refugee population. The settlement of these populations generates significant changes of entire neighbourhoods. Thus, refugees should not be considered only as recipients of humanitarian assistance, waiting for an eventual return or resettlement to a ‘third country’, but also as actors who contribute, through their initiatives and coping strategies, to the development of the cities that host them. In an unstable Middle Eastern political context, the settlement of different refugee populations demonstrates the importance of forced migration in urban development and its articulation with other forms of migration such as internal migration and international labour migration.

In Jordan, the physiognomy of the northern villages and cities has been deeply transformed by the settlement of refugees. The coexistence between Jordanians and Syrians is facilitated by the historical ties that bind the south of Syria and the north of the Kingdom. In some border areas, as in the northwest of Jordan or in the Beqaa valley in Lebanon, the effects of the protracted settlement of a large number of refugees had major effects for the local population. The poorest and the most marginalised populations suffer from the pressure on the rental market. In the northern cities, such as Irbid, Mafraq or Ramtha, rents have increased significantly and are inaccessible to the poorest households. Some services, such as schools or the medical sector, are also affected. For example, according to the United National Development Programme (UNDP),

with Syrian arrivals, many school classrooms are overcrowded. Many schools have adopted double schedules, which entails shortening classes to 35 minutes from 45, and means that teachers are now working overtime that they are not compensated for (UNDP 2014).

Syrian Refugee Camps in Jordan

Since mid-2012, three official refugee camps have been opened in Northern Jordan (Zaatari, Azraq and Mrajeeb Al Fhood) that host around 140,000 refugees (22% of the total registered population at the UNHCR). Zaatari camp in Northern Jordan, which has nearly 80,000 inhabitants today, is the best known for the settlement of Syrian refugees, and today is a makeshift city where prefabricated constructions and a few tents are juxtaposed. This area concentrates all the paradoxes of the Syrian presence in Jordan. Humanitarian organisations (such as UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, Save the Children, MSF, etc.) are omnipresent, symbolising the vulnerability of an exiled population deprived of resources. Unlike Iraqi refugees who arrived in Jordan after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime, mostly from the urban middle classes, and who had settled in the Jordanian capital, a large proportion of Syrian refugees today are from rural areas and therefore more vulnerable. They have limited access to the labour market, although measures to facilitate obtaining a work permit were made before the summer of 2016.

Today it is quite difficult to characterise the Syrian refugee camps, as their demographic development has been rapid due to the mass arrival of refugees in a short time. Most of the refugees arrived between mid-2012 when 50,000 were registered, and mid-2013 with more than 500,000 registered. The morphology of the camps has changed substantially, from a densely populated area where tents and prefabricated housing were situated closely next to each other to more urban areas where refugees have built small courtyards or small gardens in-between prefabricated housing structures growing vegetables. Initially, the camp of Zaatari was a settlement area for Syrian refugees. Until 2013, they had the possibility to go back and forth without particular control. Exile extending, and the number of refugees increasing significantly, the Jordanian authorities gradually started to control the camp’s entrances and exits. Today it is a closed space, and refugees wishing to leave must obtain a temporary permit that allows them to go to a medical appointment in an embassy or see relatives. Similarly, foreigners who wish to enter the camp must obtain prior authorisation from the Jordanian authorities.

The progressive closure of Zaatari refugee camp aims to better control the Syrian refugee population. This process directly impacts the socio-spatial organisation of the camp. Despite the constraints linked to strict regulations imposed by the host state in coordination with the UNHCR, the camp became an area of social and economic life. The refugees are divided by family and sometimes by village of origin. Prefabricated housing and tents have been re-arranged to create new forms of housing that allowed the creation of private spaces. Small shops (such as groceries, hair salons, or restaurants) and other small income-generating positions (such as carpenter or electrician) developed in the camp. The refugees have tried, whenever possible, to recreate a normal life in a highly constrained situation. The camp is shaped by international organisations and Non-Governmental Organisation (NGOs) but also by the dynamics generated by the refugees themselves. Despite the strict control of the camp, a city has emerged, completely shaped by its inhabitants. As soon as the camp opened, an informal economy developed throughout the different neighbourhoods of the camp. At the entrance, a shopping street – the Souk Street, referred to as ‘Champs Elysées’ by the inhabitants of the camp – has emerged. Shops of all kinds mushroomed: mobile phone shops, groceries, bakeries, small restaurants, hair salons, among others. Street vendors stroll around the camp selling all kinds of products. This street has become a central living space symbolising the economic dynamism of the refugees.

Controlling the Border: From Transit Camp to Temporary Settlement Place?

The reality of the camps is itself multiple. In the Middle East, alongside the main official camps run jointly by humanitarian organisations (local and international) and host states, there are also many other forms of encampment. In October 2016, more than 80,000 Syrians were trapped in the Ruqban transit camps east of the Syria-Jordan border, in a no man’s land between the two countries. From crossing points to enter Jordan, these spaces have become transit camps where the refugees initially were spending between one to ten days. They are now becoming places of temporary settlement where refugees spend several weeks or months. The tightening of the entry policy in Jordan has turned this entry points into a de facto camp at the border. Despite the intervention of the International Committee of the Red Cross, the humanitarian situation is extremely difficult. The question of the camps is intrinsically linked to that of asylum policy and border management. As the conflict continues, the tightening of entry policies in the territories of Syria’s neighbouring countries jeopardises the possibility of circulation for refugees with two main consequences. On the one hand, it challenges the role of transnational networks developed by refugees to adapt in their host societies. On the other hand, it contributes to the emergence of new camps at the borders of the host states, where refugees who are trying to leave the violence gather. This situation has created an incentive for refugees to seek asylum outside the Middle East, contributing to the ‘European migration crisis’. At a regional level, given the protracted nature of the Syrian refugee crisis, host states face a new dilemma: they have to facilitate their economic and social integration to avoid the development of poverty pockets while preserving the temporary nature of their presence.

Conclusion

The Syrian crisis has deeply transformed the Middle Eastern migration system. Syrians were mostly migrant workers, especially in Lebanon. Since 2011, they constitute one of the most important refugee populations since World War II. The large influx of refugees had one main consequence: the development of restrictive migration policies in the neighbouring countries. The mass arrival of forced migrants concentrated in certain areas (such as border cities and villages, or poor neighbourhoods in the main cities of the host countries) has significant local impact on host societies. The consequences of the influx of refugees in the global South – where most of the world’s refugees find asylum – are manifold. The settlement of hundreds of thousands of refugees put pressure on the rental market and can lead to the deterioration of security in some areas. In most cases, the role of the refugee population in these processes has not been evaluated. Middle Eastern countries are not an exception. The arrival of refugees, currently Syrians, often leads to this type of controversy. The development of new refugee camps has given a new dimension to the debate on the forms of settlement for refugees in the Middle East. But this reflection on the role of refugee camps is no longer confined to the Middle East region, and the Syrians have had to go through many camps throughout their quest for asylum. The camps will therefore come in different forms throughout the trajectories of refugees, oscillating between transit camps to settlement places.

Notes

[1] Interviews by Kamel Doraï and Myriam Ababsa in Sahab (Jordan) in 2016 with municipality representatives and Syrian investors.

[2] Only Palestinians from Iraq were denied entry in neighbouring countries after 2003. Three refugee camps were created at the Iraqi border with Syria to host them before being resettled in third countries.

[3] lijan al-tansiq in Arabic. On the model created in Syrian cities, these committees contribute to coordinating actions and exchange information with other groups (Napolitano 2012).

[4] Daesh is the acronym in Arabic for the Islamic State in Iraq and Sham (Bilad al Sham is an Arabic term for Mashrek including Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine). It is widely used in Arabic countries for Islamic State (IS), the group controlling a portion of the Syrian and Iraqi territories.

References

Ababsa, Myriam. 2015. “De la crise humanitaire à la crise sécuritaire. Les dispositifs de contrôle des réfugiés syriens en Jordanie (2011–2015).” Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 31, nos. 3 and 4: 73–101.

Achilli, Luigi, Nasser Yassin and Murat Erdogan. 2017. Neighbouring Host-Countries’ Policies for Syrian Refugees: The Cases of Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, 19 Papers IE Med.

Al Husseini, Jalal. 2015. “D’exode en exode: Le conflit Syrien comme révélateur de la vulnérabilité des réfugiés palestiniens.” allegralaboratory.net, http://allegralaboratory.net/dexode-en-exode-le-conflit-syrien-comme-revelateur-de-la-vulnerabilite-des-refugies-palestiniens/.

Chalcraft, John. 2009. The Invisible Cage, Syrian Migrant Workers in Lebanon. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Chatelard, Géraldine and Kamel Doraï. 2009. “The Iraqi Presence in Syria and Jordan: Social and Spatial Dynamics, And Management Practices by Host Countries.” Maghreb-Mashreq 199: 43–60.

Chatelard, Géraldine. 2002. Incentives to Transit: Policy Responses to Influxes of Iraqi Forced Migrants in Jordan, EUI Working Papers, Florence: European University Institute RSC n° 2002/50 – Mediterranean Programme Series.

Chatty, Dawn. 2010. Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Doraï, Kamel. 2015. “Les Palestiniens Et Le Conflit Syrien. Parcours De Réfugiés En Quête D’asile Au Sud-Liban.” Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 31, nos. 3 and 4: 103–120.

Doraï, Kamel and Martine Zeuthen. 2014. “Iraqi Migrants’ Impact on a City. The Case of Damascus (2006-2010)”. In Syria from Reform to Revolt, Volume 1. Political Economy and International Relations, edited by Raymond Hinnebusch and Tina Zintl, 250–265. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press.

Doraï, Kamel and Jalal Al Husseini. 2013. “La Vulnérabilité Des Réfugiés Palestiniens À La Lumière De La Crise Syrienne.” Confluences Méditerranée 87 (Automne): 95–108.

Feldman, Ilana. 2012. “The Challenge of Categories: UNRWA and the Definition of a ‘Palestine Refugee'” Journal of Refugee Studies 25, no. 3: 387–406.

Kagan, Michael. 2011. “We live in a country of UNHCR.” The UN Surrogate State and Refugee Policy in the Middle East.” UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), http://www.refworld.org/docid/4d8876db2.html.

Al Khouri, Riad. 2004. “Arab Migration Patterns: The Mashreq.” Arab Migration in a Globalized World. Genève: IOM.

Knudsen, Are. 2017. “Syria’s Refugees in Lebanon: Brothers, Burden, and Bone of Contention.” In Lebanon Facing The Arab Uprisings, edited by Rosita Di Peri and Daniel Meier, 135–154. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Krumm, Thomas. 2015. “The EU-Turkey Refugee Agreement of Autumn 2015 as a Two-Level Game.” Alternatives: Turkish Journal of International Relations 14, no. 4: 20–36.

Longuenesse, Élisabeth. 2015. “Travailleurs étrangers, réfugiés syriens et marché du travail.” Confluences Méditerranée 92: 33–47. DOI: 10.3917/come.092.0033.

Marfleet, Philip. 2007. “Refugees and History. Why We Must Address the Past?” Refugee Survey Quarterly 26, no. 3: 136–148.

Napolitano, Valentina. 2012. “La Mobilisation Des Réfugiés Palestiniens Dans Le Sillage De La ‘Révolution’ Syrienne: S’engager Sous Contrainte.” Cultures & Conflits 87: 119–137.

Sayigh, Rosemary. 1991 [1979]. Palestinians : From Peasants to Revolutionaries. London: Zed Books.

Shah, Nasra M. 2004. “Arab Migration Patterns in the Gulf.” Arab Migration in a Globalized World, Genève: IOM.

Shiblak, Abbas. 1996. “Residency Status and Civil Rights of Palestinian Refugees in Arab Countries.” Journal of Palestine Studies 25, no. 3 (Spring): 36–45.

UNDP. 2014. Municipal Needs Assessment Report. Mitigating the Impact of the Syrian Refugee Crisis on Jordanian Vulnerable Host Communities, United Nations Development Programme. http://www.jo.undp.org/content/dam/jordan/docs/Poverty/UNDPreportmunicipality.pdf.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). n.d.a. “Europe: Syrian Asylum Applications From Apr. 2011 to Oct. 2016.” http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/asylum.php.

UNHCR. n.d.b. “Syria Regional Refugee Response.” http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php.

UNHCR. 2016. “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2015.” http://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/576408cd7/unhcr-global-trends-2015.html.

UNHCR. 2017. “Jordan UNHCR Operational Update, January 2017.” reliefweb, 24 January 2017. http://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/jordan-unhcr-operational-update-january-2017.

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). n.d. “Syria Crisis.” https://www.unrwa.org/syria-crisis.

Zaiotti, Ruben. 2006. “Dealing with Non-Palestinian Refugees in the Middle East: Policies and Practices in an Uncertain Environment.” International Journal of Refugee Law 18, no. 2: 333–53.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- UNHCR, National Policies and the Syrian Refugee Crisis in Lebanon and Jordan

- Competing Logics of Security toward Syrian Refugees in Turkey and Lebanon

- Governing Movement in Displacement: The Case of North Jordan

- Demography, Migration and Security in the Middle East

- Forced Migration and Security Threats to Syrian Refugee Women

- The Jordanian Response to the Syrian Refugee Crisis from a Resilience Perspective