From the Deir el-Medina tomb workers’ strikes in 1156 BCE to Ukraine’s Euromaidan protests in 2013 CE, the parliament of the streets has stirred political change. A term popularly used in the Philippines, the parliament of the streets refers to protests and demonstrations (Tan 1982, 91). Its role in shaping the destiny of political communities invites this political and legal question: Who has the right to participate in it? This question has two aspects: what is this right and who is its bearer? The former is easier to answer: the right of peaceful assembly guarantees participation in the parliament of the streets. The question of who has this right is more complex.

The Proclamation of Teheran (1968) provides a departure point in teasing out this complexity. The Proclamation is one of the major outputs of the Teheran International Conference on Human Rights convened by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). “The laws of every country,” the Proclamation declares, “should grant each individual […] the right to participate in the political life […] of his country.” In her analysis of the Proclamation, Baroness Elles (1980, 16), the former Special Rapporteur of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and the Protection of Minorities, points out that “his country” refers to “the country of which [an individual] is a national or a citizen.” This suggests that citizens have the right to participate in the parliament of the streets. Affirming this are the different constitutions explicitly guaranteeing the freedom of assembly. However, the Proclamation is silent on the right of individuals to participate in the political life of countries where they are not citizens; thus, it does not also confirm whether non-citizens can participate in the parliament of the streets. While it does not prohibit non-citizens from doing so, it does not also declare they have the right (Elles 1980, 16).

Sharing the Proclamation’s silence is the articulation of the right of peaceful assembly in article 21 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Article 21 does not mention who is its bearer. This silence becomes salient when this right is compared with how the ICCPR articulates other political participation rights. Freedoms of expression (article 19) and association (article 22) are deliberately guaranteed to everyone. Meanwhile, formal political participations rights (article 25) are explicitly guaranteed only to citizens (Evans 2011, 110-122).

Nevertheless, it is largely understood that everyone has the right of peaceful assembly. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the foundation of international human rights law, provides in article 20 (1) that it is everyone’s right. Several resolutions of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) affirm this (see e.g. UNHRC 2014; UNHRC 2013). Meanwhile, the Declaration on the Human Rights of Individuals Who are not Nationals of the Country in which they Live (1985) proclaims that even non-citizens enjoy this right. The UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), the treaty body mandated to interpret the ICCPR, reiterates this position in their General Comment No. 15 (1986). The UN publication The Rights of Non-Citizens (2006) echoes this as well. Maina Kiai, the Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association, emphasises in his first report to the UNHRC that everyone has this right, and recommends that States ensure that non-nationals should also be able to exercise the right to freedom of peaceful assembly (UNHRC 2012, par. 13 & 84b) International law commentators also hint that either persons, individuals, or everyone has this right (see e.g. Nowak 2005; Aust, 2010; Boyle, 2010).

In this article, I will interrogate the assumption that the ICCPR guarantees the right of peaceful assembly to everyone. Specifically, I will assess whether individuals enjoy this right in countries where they are not citizens. Inspiring this assessment is the deportation from the Philippines of Thomas van Beersum. After joining the protests held during the state of the nation address (SONA) of the president in July 2013, van Beersum was deported by the Philippines, which has an immigration policy prohibiting non-citizens from joining protests and demonstrations. Some ask whether this policy violates the obligations of the Philippines under the ICCPR. Others question its compatibility with democratic norms. I will engage with both questions by weighing the action of the Philippines against one of the conditions of permissible restrictions to article 21 of the ICCPR.

The conditions are: 1) the restriction must satisfy the principle of legality, i.e. it must be “in conformity with the law;” 2) it must also meet the democratic necessity test, i.e. it must be “necessary in a democratic society;” and furthermore 3) the restriction must pursue at least one of the following legitimate aims: national security, public safety, pubic order, protection of public health or morals, or the protection of the rights and freedom of others (Evans 2011, 115). Any interference to article 21 can only be valid if it meets all three conditions.

Focusing on the third condition, I will examine whether restrictions based on citizenship with regards to the right of peaceful assembly violate the test of “necessary in a democratic society.” I will argue that, as long as the logic of nationalism remains legitimate, restricting the right of peaceful assembly of non-citizens is necessary in a democratic society, if the specific assembly non-citizens joined is related to the conduct of public affairs. This argument is based on appreciating the entanglement of territorial sovereignty, democracy, and nationalism in the international political order, which in turn informs the international legal order.

Spencer and Wollman (2002, 2-3) define nationalism as the ideology that “imagines the community in a particular way (as national), asserts the primacy of this collective identity over others, and seeks political power in its name, ideally (if not exclusively or everywhere) in the form of a state for the nation (or a nation-state).” Democracy is a political order in which sovereignty belongs to the demos whose will serves as the basis of the legitimacy of the power of the government which exercises that sovereignty on their behalf (Dahl 1989, 107-18; Geuss 2001, 110-19; Crick 2002, 11-13; Dahrendorf 2003, 101-114; UNGA 2014). In a democratic society, the demos have the right to participate in the conduct of public affairs. The logic of nationalism equates the demos with citizens (Nodia 1992, 7). Following this logic, non-citizens can be legitimately excluded from demonstrations related to the conduct of public affairs in a democracy.

In international law, the power to exclude springs from the principle of territorial sovereignty. It confers to States the “monopoly to decide” who it should include and exclude in their polities (Schmitt 1985, 13; Scalia 2012; Hayden 2008, 248-269). As it implies, excluding and including anyone from their polities is both a legitimate exercise of a State’s territorial sovereignty. The logic of nationalism provides the basis for inclusion and exclusion: citizenship, defined as formal membership in a State. The qualification for this membership has been historically prescribed by the politically dominant ethnos (Abizadeh 2012, 867-882).

After this introduction, I will reconstruct the circumstances surrounding the deportation of Thomas van Beersum. Though there have been similar incidents in other countries, I selected van Beersum’s case primarily because the Philippines has ratified both the ICCPR and the First Optional Protocol to the ICCPR. The Protocol provides a mechanism for individual complaints on violations of their rights under the ICCPR. Because of this, if van Beersum legally challenged his deportation, his case had a chance of reaching the HRC, the treaty body mandated to decide on the complaints. Then, taking a legal-historical approach, I will unpack how the principle of territorial sovereignty confers to States the right to limit the political activity of non-citizens.

Next, I will discuss whether the ICCPR grants equal political participation to citizens and non-citizens. After reviewing the jurisprudence of HRC, I will determine whether citizens can be precluded from joining in certain types of assemblies. Then, I will appraise how the democratic necessity clause has been interpreted by the HRC, as well as by the Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association. After asserting that both their interpretations are problematic, I will forward Garibaldi’s (1984) systematic interpretation of the clause. What the clause entails is that any restriction to article 21 has to satisfy the “principles recognized in a democratic society.” To determine these principles, I will examine key international documents. It will become apparent that the democratic principle arising from them will require engaging with one of the persistent problems in political theory: the boundary problem of democracy: the question of who belongs to the demos. After sketching how some political theorists tackle the boundary problem of democracy, I will use their insights to determine how the international political order currently addresses the boundary problem. Arguing that nationalism has shaped and continues to serve as a legitimate means of drawing this boundary, I will apply my analysis to the case study, which then leads to my conclusion.

The deportation of Thomas van Beersum

Calm and chaos

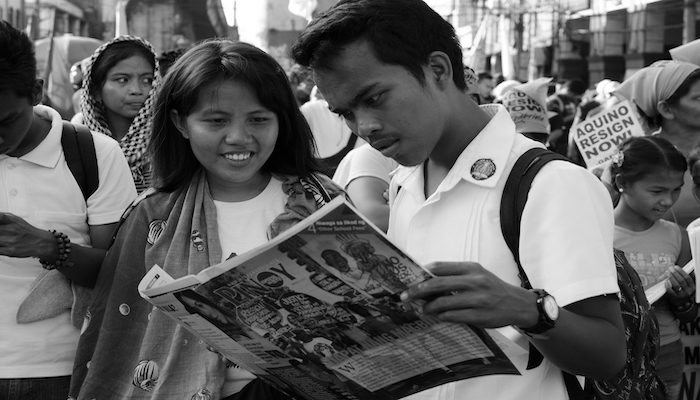

It all started with a photograph of a Dutch activist shouting at a Filipino police officer. Thomas van Beersum, a Dutch national, went to the Philippines “as part of an International Solidarity Mission and as a delegate of the International Conference on Human Rights and Peace in the Philippines” (van Beersum 2013). Joselito Sevilla is a member of the anti-riot team assigned to maintain peace and order during the annual SONA of the president. According to Rem Zamora (ABS-CBN News, June 23, 2013), the photographer who captured and witnessed van Beersum’s encounter with Sevilla, the protests started peacefully, but calm gave in to chaos when the protestors and police clashed.

Which side stirred the pot first depends on whom you believe. The clash began, Zamora (ABS-CBN News, June 23, 2013) said, after the protestors broke the police line. The anti-riot police, he said, “tried to block them, but the protestors pushed through.” Meanwhile, van Beersum (2013) blamed the police. The protestors were peaceful, he claimed, “they were attacked simply because they exercised their constitutional right to assembly and protest.” Despite their difference, both agreed that Sevilla remained calm and even gave a peace sign. However, this gesture did not stop van Beersum from confronting Sevilla. Lashing out at Sevilla, he asked why the police were hurting them. Calmly, Sevilla told him they were just maintaining peace and order. Van Beersum kept shouting. The clash raged on. Then stress, hunger, and heat burst Sevilla to tears. Two protestors hugged him, assuring him that all would be fine. These moments were captured by Zamora’s lens. The photos were featured in news networks, widely-circulated online, precipitating a national debate.

Van Beersum was widely panned. Etta Rosales, the chairperson of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), said that he “has no business in the rally. It’s not his business shouting at an official” (as quoted in Rappler, July 23, 2013). An online petition seeking his deportation and a Facebook page entitled Filipinos against Foreign Interference in Filipinas, surfaced days after his photograph with Sevilla went viral (Philippine Star, July 25, 2013). To his defence, van Beersum published an open letter to Sevilla, explaining why he joined the protests. Invoking solidarity, he wrote “I attended the SONA protest because I had been outraged by the human rights violations committed by the corrupt Aquino regime.” After he posted it on his Facebook account, it elicited comments ranging from sympathetic and embracing to mean and exclusionary.

Undesirable

The Bureau of Immigration (BOI) used van Beersum’s open letter as evidence for his deportation. They were unmoved by van Beersum’s passionate plea. For them, his intention was not as relevant as the conditions of stay attached to his visa. On August 1, 2013, a deportation order was issued against van Beersum. Along with finding that van Beersum overstayed his visa, the BOI deportation order mentioned that the open letter of van Beersum (BOI 2013, par. 6) revealed that

his real intention in coming to the [Philippines] is not for tourism, business, or for pleasure but to protest against the Government and engage in partisan political activity which prove him undesirable and in violation [of] the limitation and condition under which he was admitted as a non-immigrant.

The Order was served in the morning of the 6th of August while van Beersum checked in for his flight back to the Netherlands. He was detained at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport for the purpose of questioning and verification (Interaksyon, August 6, 2013), whereupon he was provided with a lawyer.

One of those who immediately criticised van Beersum’s detention was Renato Reyes, secretary general of the leftist group Bagong Alyansang Makabayan. Van Beersum was not the first one, he said. The Philippines has a long standing policy against foreigners participating in the street parliament. As Reyes notes, “this is not the first time this has happened as other foreign activists have also been held before by immigration officials only to be deported and then blacklisted” (as quoted in Interaksyon, August 6, 2013).

An established State practice

Van Beersum’s deportation incited reactions against the Philippine immigration policy. They were structured around two general themes: one centers on its compliance with international human rights law; while the other pertains to its conformity with democratic norms.

The compliance issue was raised by Carlos Conde, a researcher in the Asian division of Human Rights Watch (HRW). Conde (2013)wrote on the website of HRW that the Philippines violated the guarantees of free expression and peaceful assembly to which foreign visitors as well as Philippine citizens are entitled under international law.

The editorial of the Philippine Daily Inquirer (2013) addressed the conformity issue. The Inquirer tagged the policy “counterdemocratic,” insisting that “it paints a portrait of the Philippines as a place where visitors lose their rights to free expression or to assembly because they are visiting.” The editorial rhetorically asks: “What are we, North Korea?” Given that North Korea is now the poster country of anything deplorable, this comparison ensnares people to think that BOI’s policy is undesirable. However, this policy is anything but unique to a regime deemed undemocratic.

The constitutions of sixty-four countries, which include the United States, Denmark, Mexico, India, and South Korea, do not guarantee the right of peaceful assembly to everyone: either it is guaranteed only to citizens, inhabitants, the people, or, in the special case of Cuba, only to the working class. Also included in this group are Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, and Singapore, fellow members of the Philippines in the Association of Southeast Asian Nation. In 2012, Malaysia even enacted the Peaceful Assembly Act, prohibiting non-citizens from organising and participating in an assembly.

Furthermore, immigration policies restricting the political activity of non-citizens are not peculiar to the Philippines. The visa application form of Singapore even requires applicants to sign a declaration, which includes an undertaking not to take part in any political activity during their stay. Doing so renders them an “undesirable or prohibited immigrant under the Immigration Act” (Form 14A). In 2007, Cuba deported tourists who joined a march organised by Ladies in White, a Cuban dissident group. “Tourists,” the Cuban government explained, “have no business meddling in Cuba’s internal affairs and have in the past deported numerous foreigners who support local dissidents” (as quoted in Reuters, December 10, 2007). And in February 2012, India deported Rainer Hermann Sonntag, a German tourist, for participating in an anti-nuclear demonstration. Sonntag, the Indian government asserted, violated the conditions of his stay as a tourist (The Australian, March 1, 2012).

These comparisons do not absolve the Philippines from its international human rights obligations. They only bring to light one of the most deeply entrenched practices in international relations: the exclusion of non-citizens from the territories of sovereign States. This practice flows from the principle of territorial sovereignty, which confers to States the power to determine who can participate in the political life of their countries.

The power to exclude

Territorial sovereignty

The principle of territorial sovereignty grants States the supreme and exclusive authority within their own territory (Mcgrew 2011, 24). It entitles States to exclude “external actors” from their territories (Krasner 1999, 20). It confers to them the “monopoly to decide” on the conduct of their internal affairs (Schmitt 1985, 13). Because of this principle, States have the “inalienable right” to shape their own political, economic, social, and cultural systems “without interference in any form by another state” (UNGA 1965, Art. 5).

This conceptualisation of territorial sovereignty took a while to mature. The Peace of Westphalia (1648) is generally considered as the “critical event” in the development of this principle (Krasner 2001, 35). The Peace is comprised of the treaties of Münster and Osnabrück, which ended the Thirty Years War. According to Croxton (1999, 591), the idea of “exclusive spheres of authority” was not in the treaties themselves but emerged as a “consequence” of their negotiations. Absent in the treaties as well, Branch points out, is the concept of territory essential to the principle of territorial sovereignty. These treaties, Branch observes, still follow the medieval notion of territory: a “series of places, with authority radiating outward from centres rather than inward from linear boundaries” ( 2011, 282).

The concept of territory essential to the principle of territorial sovereignty is a territory with delineated boundaries. This emerged in the 16th century as European powers employed the rediscovered Ptolemaic cartographic grid techniques in mapping the Americas. While European colonial powers neatly divided the New World into non-overlapping territorial spaces, the Old World continued to be organized according to the medieval conception of territory. The shift from medieval to modern territoriality took place after the Napoleonic wars. The post-Napoleonic settlements defined territories according to their frontiers, and consequently authority got defined according to its boundaries: exclusive within a bounded territory. This consolidated the principle of territorial sovereignty which became “the constitutive basis of European (and eventually global) statehood [and] has remained relatively fixed” (Branch 2011, 284-291).

The power to exclude non-citizens

When it developed in the 17th and 18th century, the power to exclude or expel non-citizens has been widely recognized but “sparingly” exercised (Waldman 1999, 14). Territorial sovereignty as essentially the power to exclude flowed from legislation and jurisprudence responding to the rising anti-immigrant sentiments by the end of the 19th century. Prior to this, not much of a difference existed between the freedom of movement of citizens and non-citizens. Immigration policies were very lenient and “freedom of movement was encouraged” (Nafziger 1983, 815).

However, before the 19th century ended, prompted by nationalism and protectionism, governments began to refuse entry to certain non-citizens. Non-citizens were those with “clearly identifiable ethnic minority whose presence was perceived to pose an economic threat to the majority.” For England, these were the Jew; for United States, Canada, and Australia, the Chinese. Legislations restricting Chinese immigrations were passed in these latter countries, heralded by the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) of the US (Waldman 1999, 16-17).

The validity of the Chinese Exclusion Act was challenged in the US Supreme Court case Chae Chan Ping v. United States (1899). The case involved Chae Chan Ping, subject of the Emperor of China, who lived and worked in California. After he visited China in 1875, he was prevented from returning to San Francisco after the Act was passed. The Court confirmed the validity of the Act and advanced the doctrine of territorial sovereignty as essentially the power to exclude non-citizens. Highly influenced by the surge of nationalist sentiments, Chae Chan Ping v. United States elevated the power to exclude non-citizens from a historically contingent feature of territorial sovereignty to an essential part of a nation’s independence.

By the turn of the century, “leading jurists and international law commentators” adopted this view (Waldman 1999, 18). After the Great War and the Great Depression, States further exercised their power to exclude by enacting comprehensive restrictive immigration policies (Nafziger 1983, 808). After the Second World War, the power to exclude and expel non-citizens was legislated by virtually all States and it was exercised routinely (Waldman 1999, 18).

At the end of the 19th century, The Tillett Case (1899) affirmed the right of States to exclude non-citizens. This time, the focus was not to restrict their economic but their political activities. Since then, restricting the political activities of non-citizens has become a legitimate exercise of the power to exclude. As Evans notes, “as far as international law is concerned, a State may restrict the political activity of aliens by expelling those who engage in such activity” (1981, 23).

Meanwhile, various international documents further legitimised the restrictions on political activities of non-citizens. That non-citizens should refrain from engaging in political activities in another country is even proclaimed as a “duty” in Article XXXVIII of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man (1948). Across the Atlantic, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789), one of the foundations of modern human rights, does not grant political participation rights to man qua man. Meanwhile, article 16 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) states that the articles guaranteeing freedom of expression (article 10), freedom of peaceful assembly (article 11), and freedom from discrimination (article 14) cannot “be regarded as preventing the High Contracting Parties from imposing restrictions on the political activity of aliens.” It took the Council of Europe thirty-seven years following the adoption of the ECHR to ensure equality between citizens and non-citizens in terms of political participation rights at a local level. In 1992 the Council adopted the Convention on the Participation of Foreigners in Public Life at Local Level. However, the Convention falls short of guaranteeing equal political participation rights to all non-citizens; it only addresses the rights of resident non-citizens.

Also, different constitutions contain provision on restricting the political activities of non-citizens. For example, the constitutions of Costa Rica, Georgia, Mexico, Papua New Guinea, Sweden, Turkey, and Vanuatu allow for such restrictions. Commenting on these constitutional restrictions, Elles has implicated territorial sovereignty as the rationale behind them (1980, 38).

Not an absolute right

However, the right to exclude is not absolute. From the beginning of the 20th century, there have been initiatives restraining territorial sovereignty.

Three international arbitral cases involving Venezuela emphasised that this right cannot be arbitrarily exercised: the Paquet (1903), Boffolo (1903), and Maal (1903). Though they found that Venezuela exercised its power to exclude arbitrarily, they did not deny but strengthened the notion that this power is inherent in every State and that they “may exercise large discretionary powers” in determining whether a non-citizen can be expelled or excluded (Maal Case, 731). Another notable feature of these cases, especially Boffolo and Maal, is that they affirm the right of States to expel non-citizens for political reasons as long as the manner of expulsion is humane.

After the Second World War, a new standard of evaluating the rightful exercise of this power emerged: human rights treaties. These treaties have provided “significant restrictions on a state’s dealings with non-citizens” (Waldman 1999, 3). ICCPR is one of these treaties. Though it does not give unfettered freedom to non-citizens, restrictions to their rights, such as their political rights, are permissible as long as the restriction satisfies all the conditions of permissible restrictions provided by the relevant article.

Boundary of political participation

Preliminary issue

Does the ICCPR allow individuals to take part in the political life of a country where they are not citizens? Interpreting the ICCPR using the teleological method, one may be inclined to say yes. Because the object and purpose of the ICCPR is to guarantee civil and political rights to all individuals, it follows that citizens and non-citizens have equal civil and political rights unless when the right is explicitly guaranteed to citizens.

David Weissbrodt, the former Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Non-Citizens, endorses this position. He observes that the ICCPR only permits distinctions between citizens and non-citizens on “two categories of rights: political rights explicitly guaranteed to citizens; and freedom of movement.” Because of this, he argues, when it comes to political communication rights, citizens and non-citizens are on equal footing (Weissbrodt 2008, 46).

However, a contextual analysis of the ICCPR reveals a contrary perspective. The drafters of the ICCPR seemed to have an understanding that citizens and non-citizens do not have equal political rights, which is reflected in the travaux préparatoires of the ICCPR related to the right against discrimination (article 26). During the discussion on the status of non-citizens, there was a proposal to change “to guarantee to all persons…” to “citizens.” However, this was withdrawn because “it was generally felt that neither the denial of certain civil or political rights to aliens, nor the nationalization of foreign property under certain conditions, constituted discrimination within the meaning of article [26]” (as quoted in Bossuyt 1987, 490).

Furthermore, the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1950), Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons (1954), and the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (1990) cast a doubt that full political participation of non-citizens in non-electoral politics is guaranteed. Among these human rights treaties, only that on migrant workers provides some political participation rights. Nonetheless, it mention no right of peaceful assembly. Freedom of expression might be suggested to be covering it; but the text of this right does not seem to cover protests and demonstrations. This right, the article says, “shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art or through any other media of their choice.” The right to participate in trade unions may allow for freedom of assembly, if the assembly is an “activity of trade unions and of any other associations.” This is a very limited exercise of the right of assembly and only guarantees it to migrant workers and members of their families.

Nonetheless, there is an international instrument that may support the proposition that non-citizens enjoy non-electoral political participation rights: the Declaration on the Human Rights of Individuals Who are Not Nationals of the Country in which They Live (1985).

The Declaration has two significant features. First, it has a nuanced conception of non-citizens. It divides non-citizens into two general groups: 1) non-resident non-citizens, referring to individuals who are not citizens “of the State in which he or she is present” (article 1); and resident non-citizens, those who are “lawfully residing in the territory of a State” (article 8). According to the Declaration, all non-citizens enjoy the political participation rights of expression and peaceful assembly (article 5.2). Still, the right to join associations is only reserved for resident non-citizens (article 8.1.b). And second, the Declaration requires the balancing of state sovereignty and rights of non-citizens.

Before articulating the rights of non-citizens, Article 4 declares that non-citizens “shall observe the laws of the State in which they reside or are present and regard with respect the customs and traditions of the people of that State.” This is genuflecting to one of the powers flowing from territorial sovereignty: the right of States to legislate and apply that legislation to any person within their territories (Aust 2010, 43). And preliminary to enunciating political participation rights, article 5 (2) provides that these rights can be restricted as long as the restriction is

prescribed by law and which are necessary in a democratic society to protect national security, public safety, public order, public health or morals or the right rights and freedom of others, and which are consistent with the other rights recognized in the relevant international instruments and those set forth in this Declaration (article 5).

Just like the arbitral cases discussed in the preceding section, this Declaration is more an attempt to shape the rightful exercise of sovereign power than a move to fizzle out the right of States to exclude non-citizens from their political life.

In van Beersum’s case, this means that he has to respect the immigration policy of the Philippines, which restricts the participation of non-citizens in the parliament of the streets; but this restriction, an exercise of the power to exclude, cannot be applied arbitrarily. The Philippines has to justify that restricting the participation of non-citizens in a specific demonstration can satisfy the conditions for permissible restrictions of the right of peaceful assembly articulated in article 21 of the ICCPR.

Not all assemblies are created equal

The reasoning above entails determining whether the demonstration van Beersum joined can be subjected to citizenship restrictions. In general, when States make distinctions between citizens and non-citizens in the exercise of the right of peaceful assembly, the distinction may be considered discrimination under article 26 of the ICCPR. However, the right of peaceful assembly can be considered a political right, hence can be denied to non-citizens, “depending on the purpose of the [assembly]” (Tiburcio 2001, 197). Thus, this requires evaluating the purpose of the demonstration in order to determine whether participation to it can be restricted to non-citizens.

The evaluation process can be inferred from the decision of HRC on Mümtaz Karakurt v. Austria (2002). A Turkish citizen living and working in Austria, Mümtaz Karakurt was elected into the work-council of the Association for the Support of Foreigners. Because Krakurt was not an Austrian citizen, his colleague filed a case to strip him of his elected position. The Linz Regional Court ruled against Karakurt, citing the Industrial Relations Act, which requires members of work-councils to be citizens. After the Supreme Court upheld the ruling, Karakurt filed a complaint to the HRC, alleging that in using the Act against him, the Austrian courts violated his right against discrimination guaranteed under article 26 of the ICCPR.

In its defence, Austria argued that this case has to be decided not solely on the basis of article 26 but “in conjunction with article 25, as the right to be elected to work-councils is a political right to conduct public affairs under article 25.” By making this link, Austria’s application of the Act against Karakurt is justified because article 25 is only guaranteed to citizens.

The HRC was not against Austria’s move to make this link, it only found that there was no link after appreciating “the function” of the position in question. Being elected in a private company’s work-council, the HRC reasons, is not related “to participation in the public political life of the nation.” Thus, the distinction between citizens and non-citizens is not reasonable in this particular case (Mümtaz Karakurt v. Austria 2002, par. 5.3 & 8.2).

This decision implies that the distinction between citizens and non-citizens can be made in the application of certain political rights. This process rests on establishing a link between the right being exercised and the right protected by article 25, “the right to take part in the conduct of public affairs,” which the HRC articulates as “the right to participation in the public political life of the nation.” To establish this link, the purpose of the activity being protected by the right being linked to article 25 has to be determined; and this determination must be undertaken on a case by case basis, as the HRC stresses, “it is necessary to judge every case on its own facts” (Mümtaz Karakurt v. Austria 2002, par. 8.4).

In this paper, the right being linked to article 25 is article 21 (the right of peaceful assembly). Consequently, if the protest van Beersum joined in the Philippines can be considered participating in the conduct of public affairs, then restricting his participation in it is reasonable because he is not a citizen.

How can it be established whether a specific protest is related to the conduct of public affairs? Paragraph 5 in HRC’s General Comment No. 25 (1996) provides a hint. Accordingly, a specific demonstration can be considered as taking part in the conduct of public affairs, if its purpose is “to exert influence over the exercise of political power, in particular the exercise of legislative, executive, and administrative powers.”

The protest van Beersum joined falls under this category. Demonstrations during the annual SONA aim to influence the exercise of political power in the Philippines. During SONAs, the road leading to the Batasang Pambansa Complex, the headquarters of Philippine Congress, serves as the venue of the street parliament. As the elected parliament listens to the report of the Philippine president, its parallel outside takes the president to task. Participating in SONA protests is participating in the political life of the Philippines. Thus, restricting the participation of non-citizens in them can be considered reasonable. However, this does mean that the restriction has already satisfied all the conditions of permissible restrictions provided in article 21. The next section weighs this restriction against one of the conditions: the democratic necessity test. It asks: Is it necessary in a democratic society to restrict the participation of non-citizens in demonstrations related to the conduct of public affairs?

Interpreting the “necessary in a democratic society” clause

The democratic society clause is either scarce or absent in international human rights conventions (Pippan 2010, 16). In the ICCPR, it can only be found in articles 21 (right of peaceful assembly) and 22 (freedom of association). Both articles express this clause in the same way

No restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right other than those imposed in conformity with the law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

The HRC interprets the paragraph in two ways. In its jurisprudence on article 22, the HRC considers that any restriction to the right of freedom of association “must cumulatively meet” the conditions of (a) legality; (b) legitimate aim; and (c) democratic necessity, “for achieving one of the legitimate aims” (Jeong-Eun Lee v. Republic of Korea 2005, par. 7.2). Meanwhile, its jurisprudence on article 21 combines the democratic necessity and legitimate clauses. Instead of three conditions, the restriction only has to satisfy two: “(a) in conformity with the law; and (b) necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals or the protection of rights and freedom of others” ( see e.g. Elena Zalesskaya v. Belarus 2011, par. 10.6; Syargei Belyazeka v. Belarus 2012, par. 11.7; Dennis Turchenyak et al. v. Belarus 2013, par.7.4).

Meanwhile, Kaina (UNHRC 2012, par. 17), in his report to the UNHRC, relied on the interpretation made by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). In its jurisprudence, the ECtHR interprets the word “necessary” as “pressing social need” (Handyside v. UK 1976, par. 48). It has also identified pluralism, tolerance, and broadmindedness to be the “hallmarks of a democratic society” (Young, James and Webster v. UK 1981, par. 63; Chassagnou and Other v. France 1999, par. 112; Gorzelik and Others v. Poland 2004, par. 89 ). The ECtHR asserts that without these three principles democratic society cannot exist. This interpretation, however, cannot be thoughtlessly used to interpret the democratic necessity clause in the ICCPR.

Sources of international law exist and apply separately even if they have identical content (Nicaragua v. United States of America 1986, par. 175-179). Hence, even if the ECHR and ICCPR have identical contents they remain separate, and they have to be interpreted separately in their own contexts. At best, the interpretation of the ECtHR serves as a guide but it cannot be the authoritative interpretation of the democratic necessity clause in the ICCPR because of their different contexts.

Garibaldi (1984) has undertaken this contextual analysis by evaluating the function, i.e. syntactic role, of the “necessary in a democratic society” clause in the provision where it can be found. By understanding this function, its purpose can be known. “From the point of view of syntaxis,” he considers the clause as a modifier of the word restrictions. By modifying restrictions, the clause provides a “standard of legitimacy” that any restriction to the right must meet in order to be valid, i.e. the restriction itself must be necessary in a democratic society. Thus, for a restriction to be valid, Garibaldi argues, it has to satisfy the principles recognized in a democratic society (1984, 26-40).

Reviewing the travaux préparatoires of article 21, it seems that this is also the intention of the drafters when they introduced the clause

The supporters of this proposal expressed the opinion that freedom of assembly could not be effectively protected if the State parties did not apply the limitations clause according to the principles recognized in a democratic society. (Bossuyt 1987, 418).

Thus, the validity of precluding non-citizens from joining demonstrations related to the conduct of public affairs depends on whether this preclusion can satisfy the “principles recognized in a democratic society.” What are these principles? In order to know them, one first needs to define democracy in the context of an international treaty. This is a difficult task.

Democracy in international law

Part of the difficulty of defining democracy in the context of an international treaty is the fact that no “fully concretised notion of democracy [exists] in international law” (Saul 2012, 568). In turn, this imposes difficulty in knowing what the principles recognized in a democratic society are. One may be tempted to import to the international level the principles of democracy developed in the jurisprudence of the ECtHR, just like Kaina (UNHRC 2012) did. This is problematic.

The principles ECtHR identified emerged from the political history of the European political order. They may be the principles of democracy recognized in the democratic society imagined in that political order; but, as Garibaldi(1984, 68) argues, they are not automatically the principles of democracy envisaged in the international political order, the political context from which the ICCPR emerged.

Some UNHRC resolutions provide a starting point. In its preamble, the Promotion of a Democratic and Equitable International Order (2014) defines democracy as “based on the freely expressed will of the people to determine their own political, economic, social and cultural systems and their full participation in all aspects of their lives.” Meanwhile, the resolution on Equal Political Participation (2013) provides that “the will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government.” This means that a society is democratic, if the exercise of political power in that society is based on the freely expressed will of the people. In such a society, in order to be able to exert influence on the exercise of political power, the people should have the right to take part in the conduct of public affairs. The principle of democracy arising from this discourse is the principle of equal political participation, which the latter resolution recognizes as “critical […] for democracy.”

The question now is: Do restrictions on the participation of non-citizens in demonstrations related to the conduct of public affairs satisfy the principle of equal political participation as understood in the international political order? The answer depends on whether non-citizens are included in the demos.

Who belongs to the demos?

The boundary problem

The above-mentioned UN resolutions identify the will of the people as the ground of the legitimate exercise of political power. As a standard of political legitimacy, democracy “demands that the human object of power, those persons over whom it is exercised, also be the subject of power, those who (in some sense) author its exercise” (Abizadeh 2012, 867). However, this “self-referential theory” of the legitimate exercise of power, Abizadeh argues, has to address the question of who belongs to the people “before the question of legitimacy can be determinately answered”.

In democratic theory, the question of who belongs to the demos is referred to as “the boundary problem,” or the “problem of inclusion” (Whelan 1983, 13-47; Dahl 1989, 119). Political theorists engage with it in various ways. The demos is historically contingent, Schumpeter (1976, 245) argues; hence the boundaries of the demos is better left to “every populus to define. Some offer normative criteria in dealing with the boundary problem. Dahl (1990) asserts that everyone affected by the decision of a government has the right to take part in the conduct of governance. Building on Dahl, Goodin (2007) proposes that the demos should be composed not just of those who are actually but all those possibly affected by a decision. However, this still draws a boundary between those who belong and who do not belong to the demos on the basis of having interests affected by a decision. Abizadeh (2012, 867-882)rightfully points out that defining the boundaries of the demos is in itself an exercise of political power. Because democracy demands that the object of power is also the subject of power, drawing boundaries can only be democratic if it is legitimized by those who subjected to this boundary: everyone. That is why Abizadeh asserts that, in principle, the demos is “unbounded”.

In dealing with the boundary problem of democracy, the international political order seems to operate with an amalgam concept of the demos bred from a dynamic combination of Schumpeter’s “historically contingent demos” and Abizadeh’s “unbounded demos.” The demos in the international political order is a fluid concept: in principle it is unbounded, but its boundary is drawn by historically contingent forces. This can be gleaned from various international documents.

The UN resolution on Equal Political Participation (2013) equates people with citizens and uses them interchangeably. Adopted without a vote, the resolution uses citizenship to demarcate the boundary of the demos. After declaring that “the will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government,” it forbids distinctions “ among citizens in the enjoyment of the right to participate in the conduct of political and public affairs.” This implies that non-citizens are not part of the people whose will serves as the basis of political power. By equating the will of the people with the will of the citizens, the resolution endorses a bounded political community demarcated by citizenship.

The decision of who can be a citizen, and therefore who can be part of the demos, is a function of sovereignty. In its advisory opinion on Nationality Decrees Issued in Tunis and Morocco (1923), the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) notes that the conferment of citizenship is “within the jurisdiction of a State.” However, “the question whether a certain matter is or is not solely within the jurisdiction of a State is an essentially relative question; it depends upon the development of international relations.” The PCIJ provides no definite answer on how to draw the boundary of citizenship. The legitimacy of this boundary is an essentially relative question, which depends upon factors contingent on the development of international relations. That the legitimate boundary of citizenship is essentially relative implies that in principle citizenship is unbounded and that this boundary is only drawn in practice by historically contingent forces.

Nationalism is that force drawing the boundary of citizenship, and therefore of the demos. “Whether we like it or not,” Nodia (1992, 7) remarks, it “has provided the political units for democratic government.” Its logic equates the demos with the nation, reflecting the characteristics of the dominant ethnos (Abizadeh 2012, 869; Hoerder 2012, 548).

The spectre of nationalism

The Big Bang of nationalism, the French Revolution disentangled sovereignty from monarchical and religious authorities and grounded it in the nation (Hobsbawm 1962, 178; Livesey 2001, 202; Spencer and Wollman 2002, 122.) This disentanglement promoted “the notion that sovereignty rests on the consent of the governed, that the state is the expression of the will of the people” (McNeill and McNeill 2003, 227). With this new notion of sovereignty came the fusion of nation and people, which eventually started the long marriage between nationalism and democracy (Nodia 1992, 7). Since then, the logic of nationalism spread globally because of Western colonial projects. After the wave of decolonisation, nationalism became “the organizing principle” of post-colonial states (Hoerder 2012, 548). The allure of nationalism rests on its ability to promote a strong “sense of solidarity,” thereby satisfying “what is probably among the deepest human cravings, the urge to solidarity and community, the urge to divide humanity into ‘us’ and ‘them’” (McNeill and McNeill 2003, 228).

The logic of nationalism, it seems, came to stay. Its power and efficacy is evidenced by how international law uses citizenship and nationality interchangeably. Its logic is reflected in citizenship laws, alternatively called nationality laws, which “distinguish between nationals who were considered to be an integral part of a given society and those who were aliens or outsiders” (Waldman 1999, 14). Even the right of self-determination, the first right in the ICCPR, has an intimate relationship with nationalism. As Summers (2005, 331) notes, “self-determination assumes that the basis for legitimate political authority is a nation or a people. In doing so it uses the nation or people as a political idea which forms the model for that authority.”

Immigration controls exemplifies the logic of nationalism. Flowing from the principle of territorial sovereignty, immigration controls guard the entry of non-citizens and impose conditions of stay on those who are admitted. As I have shown, the emergence of strict immigration laws was driven by nationalism; though restrained, it remains legitimate. The HRC also respects this practice. The ICCPR, the HRC says in General Comment No. 15, “does not recognize the right of aliens to enter or reside in the territory of a State party. It is in principle a matter for the State to decide who it will admit to its territory.” Nonetheless, the HRC says, “once aliens are allowed to enter the territory of a State party they are entitled to the rights set out in the [ICCPR],” including right of peaceful assembly.

This is not necessarily the case. As I have argued, restricting the right of peaceful assembly of non-citizens is necessary in a democratic society if the assembly is related to the conduct of public affairs, which is only reserved for citizens. Nevertheless, this restriction is only legitimate if it satisfies all the three conditions of permissible restrictions provided in article 21 of the ICCPR: the legality tests; democratic necessity test; and the legitimate aim test.

Conclusion

Because of the principle of territorial sovereignty, every sovereign State possesses the power to exclude non-citizens from their polities. One way this power is implemented is through immigration controls, which determine who can be admitted as well as the conditions of stay of those who are. Though the regime of international human rights restrain this power to exclude, it remains an essential feature of sovereignty because of the force of nationalism. Nationalism has fashioned not just the exercise of the sovereign right to exclude, but also the boundaries of the demos. The logic of nationalism has equated the demos with citizens, defined according to the characteristics of the dominant ethnos. This equation reduces the will of the people to the will of the citizens. This is reflected in the principle of equal political participation negotiated in the UN General Assembly, which guarantees the right of citizens to participate in the conduct of public affairs in their own countries.

History has not yet taken a different route, and keeps marching on the road nationalism paved, in which territorial sovereignty, nationalism, and democracy are entangled. This entanglement is palpable in the case of Thomas van Beersum. His deportation is “a vivid practical demonstration, far more compelling than imprisonment, that the individual concerned lies outside the state’s abstract political community” (Gray 2011, 577).

The question of whether or not excluding non-citizens from non-electoral political activities is necessary in a democratic society ultimately depends on the decision of the citizens of the democratic society in question. No matter how strong the influence of nationalism is, the existing boundary of the democratic political community is not final. Its perimeters are historically contingent, subject to political contestation and therefore legal reconfiguration. After all, as the poet Kay Ryan versed: “Order is always starting over.” Our current one is no exception.

References

Abizadeh, Arash. 2012. “On the Demos and its Kin: Nationalism, Democracy, and the Boundary Problem.” American Political Science Review 106 (4): 867-882.

American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man (1948).

Aust, Anthony. 2010. Handbook of International Law. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boffolo Case. 1903. Reports of International Arbitral Awards. Volume 10. United Nations.

Bossuyt, Marc J. 1987. Guide to the “Travaux Préparatoires” of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Dordrecht: Marinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Boyle, Kevin. 2010. “Thought, Expression, Association, and Assembly.” In International Human Rights Law, edited by Daniel Moeckli, Sangeeta Shah and Sandesh Sivakumaram, 257-279. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Branch, Jordan. 2011. “‘Colonial Reflection’ and Territoriality: The Peripheral Origins of Sovereign Statehood.” European Journal of International Relations, 18 (2): 277-297.

Bureau of Immigration. 2013. Deportation Case Against Van Beersum Thomas Alexander. S.D.O. BOC-13-SBM-25, August 1.

Chassagnou v. France. 1999. App nos 25088/94, 28331/95 and 28443/95. ECHR, April 29.

Nicaragua v. United States of America. 1986. Merits, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports.

Gorzelik and Others v. Poland. 2004. App 44158/98. ECHR, February17.

Chae Chan Ping v. United States. 1899. 130 U.S. 581.

Conde, Carlos. 2013. “Dispatches: Philippines Should Revoke Blacklisting of Protester.” Human Rights Watch, August 7. Accessed January 10, 2014, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/07/dispatches-philippines-should-revoke-blacklisting-protester.

Crick, Bernard. 2002. Democracy: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Croxton, Derek. 1999. “The Peace of Westphalia of 1648 and the Origins of Sovereignty.” The International History Review, 21(3): 569-852.

Dahl, Robert A. 1989. Democracy and its Critics. New Haven: Yale University.

Dahl, Robert A. 1990. After the Revolution?: Authority in a Good Society. Cincinnati: Yale University Press.

Dahrendorf, Ralf. 2003. “A Definition of Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 14(4): 101-114.

Dennis Turchenyak et al. v. Belarus. 2013. Comm no 1948/2010. HRC, July 24.

Elena Zalesskaya v. Belarus. 2011. Comm no 1604/2007. HRC, March 28.

Elles, Diana. 1980. International Provisions Protecting the Human Rights of Non-Citizens. UN document. E/CN.4/Sub.2/392/Rev. 1.

European Convention on Human Rights (1950).

Evans, A.C. 1981. “The Political Status of Aliens in International Law, Municipal Law, and European Community Law.” International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 30(1): 20-41.

Evans, Malcolm D., ed. 2011. International Law Documents. 10th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Form 14A – Application for an Entry Visa, Singapore. Accessed March 15, 2014, http://www.ica.gov.sg/data/resources/docs/Visitor%20Services/Form%2014A.pdf.

Garibaldi, Oscar M.,1984. “On the Ideological Content of Human Rights Instruments: The Clause ‘In a Democratic Society.” In Contemporary Issues in International Law: Essays in Honor of Louis B. Sohn, edited by Thomas Buergenthal, 23-68. Kehl: N.P. Engel Publisher.

Geuss, Raymond. 2001. History and Illusion in Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gray, Benjamin. 2011. “From Exile of Citizens to Deportation of Non-Citizens: Ancient Greece as a Mirror to Illuminate a Modern Transition.” Citizenship Studies, 15 (5): 565-582.

Goodin, Robert E. 2007. “Enfranchising All Affected Interests, and its Alternatives.” Philosophy & Public Affairs, 35 (1): 40-68.

Handyside v. UK. 1976. App no 5493/72. ECHR, December 7.

Hayden, Patrick. 2008. “From Exclusion to Containment: Arendt, Sovereign Power, and Statelessness.” Societies Without Borders. 3: 248-269.

Hobsbawm, Eric. (1962) 2012. The Age of Revolution: 1789-1848. Reprint, London: Abacus.

Hoerder, Dirk. 2012. “Migrations and Belongings.” In A World Connecting, edited by Emily S. Rosenberg, 435-592. Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Jeong-Eun Lee v. Republic of Korea. 2005. Comm. No. 1119/2002. UNHRC, July 20.

Krasner, Stephen D. 1999. Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Krasner, Stephen D. 2001. “Rethinking the Sovereign State Model.” In Empires, Systems, and States: Great Transformations in International Politics, edited by Michael Cox, Tim Dunne and Ken Booth, 17-42. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Livesey, James. 2001. Making Democracy in the French Revolution. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Maal Case. 1903. Reports of International Arbitral Awards. 1903, Volume 10. United Nations, 730-733.

Mcgrew, Anthony. 2011. “Globalization and Global Politics.” In The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations. 5th ed, edited by John Baylis, Steve Smith and Patricia Owens, 14-31. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McNeill J.R. and William H. McNeill. 2003. The Human Web: A Bird’s-Eye View of World History. New York: Norton & Company.

Mümtaz Karakurt v. Austria. Comm no 965/2000. UNHRC, April 4.

Nafziger, James A.R. 1983. “The General Admission of Aliens Under International Law.” The American Journal Of International Law, 77 (4): 804-847.

Nationality Decrees in Tunis and Morocco (advisory opinion). 1923. PCIJ No.4.

Nodia, Ghia. 1992. “Nationalism and Democracy.” Journal of Democracy, 3 (4): 3-22.

Nowak, Manfred. 2005. UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: CCPR Commentary. 2nd ed. Kehl: NP Engel.

Paquet Case. 1903. Reports of International Arbitral Awards, Vol. 9. United Nations.

Peaceful Assembly Act. 2012. Laws of Malaysia Act 736.

Pippan, Christian. 2010. “International Law, Domestic Political Orders, and the ‘ Democratic Imperative’: Has Democracy Finally Emerged as a Global Legal Entitlement?” Jean Monnet Working Paper 02/10.

Saul, Matthew. 2012. “The Search for an International Legal Concept of Democracy: Lessons from the Post-Conflict Reconstruction of Sierra Leone.” Melbourne Journal of International Law, 13 (1): 540-568.

Scalia, Antonin. 2012. “The Defining Characteristic of Sovereignty.” National Review Online. June 25. Accessed January 10, 2014, http://www.nationalreview.com/articles/303931/defining-characteristic-sovereignty-antonin-scalia.

Schmitt, Carl. 1985. Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. Translated by George Schwab. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1976. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. London: Allen and Unwin.

Spencer, Philip and Howard Wollman. 2002. Nationalism: A Critical Introduction. London: SAGE Publications.

Summers, James J. 2005. “The Right of Self-Determination and Nationalism in International Law.” International Journal on Minority and Group Rights, 12: 325-354.

Syargei Belyazeka v. Belarus. 2012. Comm no 1772/2008. HRC, March 23.

Tan, Samuel K. 1982. A History of the Philippines. Quezon City, Philippines: University of the Philippines.

Tiburcio, Carmen. 2001. The Human Rights of Aliens Under International and Comparative Law. The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

United Nations. 1968. Final Act of the International Conference on Human Rights: Proclamation of Teheran, May 13, 1968.

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 1965. Declaration on the Inadmissibility of Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States and the Protection of their Independence and Sovereignty. A/RES/20/2131, December 21.

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 1985. Declaration on the Human Rights of Individuals Who are not Nationals of the Country in which they Live. A/RES/40/144, December 13.

United Nations General Assembly UNGA. 2014. Promotion of a Democratic and Equitable International Order, A/HRC/RES/ 25/15, March 27.

United Nations Human Rights Committee (HRC). 1986. CCPR General Comment No. 15: The Position of Aliens Under the Covenant. HRI/GEN/1/Rev.9 (Vol. I), April 11.

United Nations Human Rights Committee (HRC). 1996. CCPR General Comment No. 25: Article 25 (Participation in Public Affairs and the Right to Vote), The Right to Participate in Public Affairs, Voting Rights and the Right of Equal Access to Public Service. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.7. July 12.

United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC). 2012. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association, Maina Kiai. A/HRC/20/27, May 21.

United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC). 2013. Equal Political Participation. A/HRC/RES/24/8, September 26.

United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC). 2014. Promotion of a Democratic and Equitable International Order. A/HRC/RES/25/15, March 27.

United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC). 2014. The Promotion and Protection of Human Rights in the Context of Peaceful Protests. A/HRC/RES/26/38, March 28.

United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC). 2013. The Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association. A/HRC/RES/24/5, September 26.

Van Beersum, Thomas. 2013. “An Open Letter to Policeman Joselito Sevilla.” ABS-CBN News, June 23. Accessed January 14, 2014, http://www.abscbnnews.com/focus/07/23/13/open-letter-crying-cop.

Waldman, Lorne. 1999. “The Limits on a State’s Right to Exclude and Expel Non-Citizens Under Customary International and Human Rights Law.” Master’s thesis, University of Toronto.

Weissbrodt, David. 2008. The Human Rights of Non-citizens. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Whelan, Frederick. 1983. “Prologue: Democratic Theory and the Boundary Problem.” In Nomos XXV: Liberal Democracy, edited by J. Roland Pennock and John W. Chapman, 13-47. New York: New York University Press.

Young, James and Webster v. UK. 1981. App no 7601/76; 7806/77. ECHR, August 13.

Written by: Sass Rogando Sasot

Written at: Leiden University College

Written for: Laurens van Apeldoorn

Date written: June 2014

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The European Parliament: A Genuine Co-legislator?

- The Gouzenko Affair and the Development of Canadian Intelligence

- Human Rights and Security in Public Emergencies

- To What Extent Can History Be Used to Predict the Future in Colombia?

- To What Extent Has China’s Security Policy Evolved in Sub-saharan Africa?

- The Anomaly of Democracy: Why Securitization Theory Fails to Explain January 6th