This is an excerpt from Conflict and Diplomacy in the Middle East: External Actors and Regional Rivalries. Get your free copy here.

When assessing the development of regional peace and cooperation, few areas are as challenging and ambivalent as the Middle East. Europe, the birth place of the modern global international society, enjoys a stable peace. Latin America is characterized by a “long peace;” and most of Africa has witnessed very little interstate war (Bull and Watson 1985; Herbst 2000; Centeno 2002). In this respect, the Middle East is somewhat of an outlier in contemporary international relations as a region marred by both frequent interstate and intrastate conflicts. Although international societies do not abolish wars per se, they do help to tame interstate conflict. This anomalous situation calls into question whether the Middle East comprises an international society. The formal inquiry is thus: to what extent does this society limit the use of force, facilitate conflict resolution, and, most importantly, provide a semblance of order?

According to one of the most authoritative studies of the Middle East from the perspective of international society and order, the Middle East features sufficiently distinct qualities to qualify as a regional society of states with its own unique sub-regional order (Buzan and González-Pelaèz, 2009). However, it remains an unstable space in which the possibility of war has not been eliminated. Moreover, the Middle East has experienced significant political upheaval since the publication of this volume, including the Arab Spring, intensification of Sunni–Shia conflict, the rise of the so-called Islamic State (hereafter ISIS, also known as Daesh and ISIL), fragmentation of important states such as Iraq and Syria, and the growth and diversification of the illicit economic activities in the region. The purpose of this chapter is therefore to examine, update, and in some cases, reinforce existing English school insights on the Middle East by way of examining the relative absence of peace – and even “productive” war (Tilly, 1992). On this point, this chapter argues that Middle Eastern international society, to the extent that it can say it preserves a stable order, is relatively weak due primarily to the interference of extra-regional great powers, the absence of a unifying vision of regional order among its diverse members, the institutional fragility of Middle Eastern states, and the prominence of violent illicit non-state actors, all of which provide means and incentives for states to pursue their narrow self-interests without sufficient regard for the broader interests of all regional states. In other words, despite overwhelming historical, civilizational, and even political affinities among Middle Eastern states, the region is characterized today by a relatively underdeveloped international society that is matched by the dysfunction of its interstate system. The chapter’s main contention is that Middle Eastern states have failed to define a raison de système due in part to the elusiveness of relevant intrastate commonalities.

After introducing the idea of “order” as a theoretical referent to frame Middle Eastern regional politics, the chapter will explore the problems of extra-regional interference in the region’s affairs, the cross-cutting conflict between Sunni and Shia states and their numerous proxies, and the persistent problem of state weakness, all of which have served to exacerbate problems such as transnational terrorism, proxy wars, illicit industries, and ethnic as well as sectarian conflict.

Regional Orders and the English School

Before delving into the matter of order in the Middle East, some conceptual clarifications are needed. By order, the present analysis refers to a stable pattern of relations among states in an international society that preserves the common interests of its constituent members despite the deleterious effects of international anarchy (Bull 1977, 1–3). There are different interpretations in the IR lexicon as to how states can achieve their primary objectives under such structural conditions. The English school, which serves as the analytical referent in this chapter, offers a via media between realist and liberal approaches by underscoring states’ interests, or raison d’état, by manifesting as a commonly-held vision of regional order, which, by virtue of being upheld, can sustain the interests of all its constituent members. This concern for the functioning of international society as a way of serving one’s own interests is known as raison de système (Watson 1990, 104–105).

Within the English school, institutions are considered as the set of practices and normative elements that serve to promote the common interests of a society by engendering order (and therefore constituting an international society). There are numerous interpretations of these institutions (C.f. Bull 1977; Buzan 2004). For the purposes of this analysis, a traditional approach emphasizing the role of War, the Balance of Power, Diplomacy, International Law, and Great Power Management should suffice (González-Pelaèz 2009, 103–104). These “fundamental” institutions exist in some form or another across regions and international societies and may exhibit unique qualities. Nevertheless, the current global international society is an offshoot of the European international society. It has served not only to ensure the orderly conduct of relations among European states, but also to curb the rise of revolutionary movements and other threatening states from becoming hegemonic. An international society ensures the independence and survival of its constituent states (Armstrong 1993, 1–5). The sine qua non for order and a properly functioning international society are therefore a common vision of order, a recognition by member states of their common interest, relative interstate peace, and stability in property rights. In this respect, the phenomenon of how states perceive and articulate security threats is of paramount importance. The idea of raison de système is a central tenant of early-modern European statecraft and in some ways a prerequisite to a balance of power. A modern rendition of the idea might possibly be explored as a form of macrosecuritisation (Buzan and Wæver 2009, 254). For a discussion of the merits of applying the idea to the Middle East, see (Malmvig, 145–148). Achieving order would necessitate a commonly held referent of, and consensus on, what constitutes a threat to the common interests of the members of an international society. Failure to obtain a common vision may compel regional states to pursue alliances with extra-regional powers or tempt them to project power through non-state actors.

The requirement for a common vision, as well as states’ recognition of each other’s common interests, is problematic in view of the imperial means by which European society came to encompass the globe. This problem is further compounded by the political and cultural diversity of international politics, which calls into question the popular notion that the international system and international society are uniform and all-encompassing arenas (Cf. Buzan and Wæver; Hurrell, 2007; Costa-Buranelli, 2015). Be they coercive or cooperative, interactions are denser within regions where independent political units share greater cultural and historical affinities, which can act as the wellspring of an international society (González-Pelaèz 2009: 114–115). Buzan notes that eggs on a frying pan serves as a better analogy for international society, as the “global egg white” represents the sine qua non values of European international society, while the “yolks” represent the dense set of interactions and sui generis values of individual regions (Buzan 2004, 208). From such a perspective, a Middle Eastern society is unproblematic, especially for Buzan, who characterizes the Middle East as a sub-global society of states with its own distinct character (Buzan 2009, 240). Nevertheless, he qualifies this statement by recognizing the possibility of significant heterogeneity (Buzan 2009; Buzan and Wæver 2003). For a “region” like the Middle East, heir to a centuries old legacy of external great power interventions, externally imposed regime changes, religious conflict, and lack of a unifying regional vision, there is no “yolk.” For all intents and purposes, the present chapter finds greater utility in thinking about regional international societies like the Middle East as being “lightly scrambled eggs”, in which an amorphous yolk is connected to the yolks of other regional international societies by way of extra-regional great powers’ involvement.

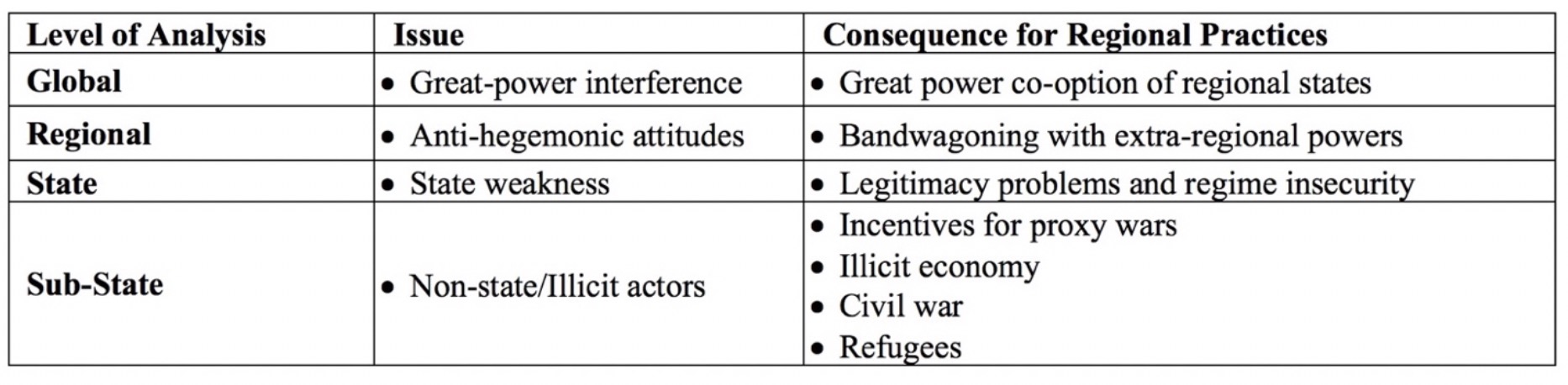

This chapter therefore explores the extent to which such logic obtains in the contemporary Middle East. To what extent do states act purposively with the view of promoting each other’s common interests — the raison de système — of Middle Eastern international society, and to what extent are the region’s dysfunctions insurmountable? Rather than analyzing the region from a structural English school framework that highlights the functioning of “primary”, “derivative”, and “secondary” institutions of international society, this chapter attempts the modest goal of clarifying some of the obstacles to the consolidation of a stronger international society in the Middle East by delving into notable problems at the global, regional, state, and sub-state levels, as well as exploring the consequences of these issues for regional order. Although it may seem impertinent to attempt to disaggregate these dynamics since they are often multi-causal and mutually reinforcing, the table below advances a useful starting point that forms the core of the present theoretical investigation.

Table 1. A summary of the intersection of issues and their regional consequences on the regional raison de système.

Global Level

The first challenge to the establishment of order in the Middle East originates from outside of the region itself, through the medium of great power intervention. This is a well-documented and perennial feature of the politics of the region that continues to create deep fault lines among its constitutive members (Halliday 2009, 6). The Middle East is a region that has frequently experienced foreign occupation and forcible regime changes, going as far back as a millennium. In fact, few homegrown regional powers have emerged in the region after the Rashidun Caliphate and its successors. Where truly powerful states emerged, their interests transcended the arbitrary geographic and political boundaries of the “Middle East”. Various iterations of Mongolian and Turkish conquerors over time prevented the development of a regional consciousness independent of the broader designs of empire builders with ecumenical ambitions extending far beyond the Middle East. Until very recently, there were no “political units” so to speak that could conceive of a separate Middle Eastern region with its own distinct logic. The very term “Middle East” was neither an administrative unit of the Sublime Porte, nor some eschatological goal for aspirants of liberty. It is as external an imposition as were many of the Westphalian values imposed on the region after the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire. The concept ironically originates from the reflections of Mahan (1902), a naval strategist from a rising world power, although epithets for the region abound (Davidson 1960).

The contemporary territorial division of the region is the result of external great power intervention, as evidenced by the patterns of state formation, state society dynamics, and the trajectories of regimes. During the Cold War, superpower competition in the region, external interventions, and alliance dynamics also served to weaken regional solidarity. The unconditional support of the US to Israel and Saudi Arabia, the Western backed coup in Iran and the eventual revolution in 1979, and political instability are revealing examples. This trend in regional security dynamics persists in the post-Cold War era as well, most notably with the successive interventions against Iraq. The First Gulf War highlights the absence of an intraregional sense of a balance of power, and the inability of Middle-Eastern states and organizations to moderate the behavior of one of its members. To ensure regional peace, Middle Eastern states deferred to a resurgent United States, which resolved the conflict through a UN-sanctioned intervention. The US-led preemptive war against Iraq in 2003 is even more controversial as it demonstrated the vulnerability of the Middle East to external intervention, as well as how extra-regional powers can use force to reengineer the region by forcibly imposing regime change.

Since the publication of International Society and the Middle East in 2009, several regimes in the region have been contested, which has drawn considerable attention and interference from great powers and states aspiring to regional leadership. The most significant of these cases is the ongoing Syrian Civil War. This conflict, in many respects resulting from the financial and material support of regional powers to various factions within and beyond Syria, features an authoritarian and purportedly secular regime in Syria, backed by Russia and Iran, versus a hodgepodge of internally divided Sunni factions backed by Gulf Monarchies and Turkey, Kurdish groups favored by the West, and ISIS. More importantly, the human rights abuses, the alleged use of chemical weapons, and the region’s incapacity (with some exceptions) to provide humanitarian assistance for refugees underscore the fundamental fragility of regional international society. These contemporary developments are important because they evidence a general lack of common vision for the region, as well as the failure of Middle Eastern states to act towards a raison de système. Instead, prominent Middle Eastern states have pursued ineffective foreign policies based on parochial conceptualizations of order; these are explored in the next section.

Regional Level

Related to the external factors above, another obstacle to the emergence of a common vision of order is that there are no great powers within the Middle East that can effectively bring to bear sufficient political influence and material capabilities to sway other states and thereby “manage” the region’s international relations. One partial explanation for the absence of Middle Eastern great powers is the region’s colonial history and the strong anti-hegemonic tendencies of Middle Eastern states inter se, as they prefer to balance with external powers against regional rivals. This may appear as a controversial point. After all, while some historical international societies coalesced around hegemonic systems (like that of the Sino-centric international society), the European international society developed in an “anarchical” setting (Kaufmann, Little, and Wohlforth 2007: 234; Watson 1990; Bull and Watson 1985; Bull 1977). However, great powers still played a decisive role in shaping their international society through peace settlements and fulfilling a “concert” function (Bull 1977, 194–222).

In the European context, great powers allowed an element of hierarchy and, by some accounts, exercised a collective hegemony that effectively helped preserve a peaceful order (Clark 2011). The Concert of Europe, while repressive in many violent ways, was successful in moderating great-power wars and revolutionary social movements that could harm the fabric of international society. There were also great powers external to the core of European international society that could enervate such developments in meaningful ways. When the European situation is contrasted to that of the Middle East, the latter remains too politically diverse to accommodate a “thicker” international society, while also lacking intra-regional great powers to collectively articulate regional interests and collaborate on achieving them. It must, however, be said that one notable vision, that of Pan-Arabism, fell apart due to an unsuccessful bid for regional leadership.

The most notable of these might have been the cases of Nasser and Sadat in Egypt and Saddam Hussain in Iraq. Although these bids were also alternatingly supported or resisted to some extent by local powers, some progress was made towards a Middle Eastern great power through the unification of Egypt and Syria, which formed the Great Arab Republic between 1958–1961. Nevertheless, this could not be sustained without further unity and political support by other relevant states. Their failure to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict combined with Egypt’s eventual normalization of relations with Israel not only dashed hopes but also undermined Egypt’s bid for the leadership of the Arab world. In the post-Cold War, Saddam’s efforts to pursue the cause of Arab states, which (he thought) entitled his state to the occupation of Kuwait, was frustrated by the Gulf War coalition led by the United States.

Not only did Pan-Arabism fail to bring unity, but the logic of the Cold War also raised Islamic identity as a popular alternative rallying idea in the face of the threat of communism. While this could have served as a much more inclusive identity, possibly appealing to non-Arab and nominally secular countries as well, culture acted as a centrifugal force. This is not to suggest an essentialist perspective. The Sunni–Shia conflict is one that harkens back to the founding of Islam in the 7th century and therefore understandably cuts across many regional cleavages. However, power and diverging interests are the root of this conflict. It is a clear manifestation of the underlying competition between US-supported “Petromonarchies” and Israel versus Iran and its proxies. Contributing to this was the successful securitization of Iran and Syria. Iran’s nuclear program, whether genuinely peaceful or “roguish,” was sufficiently threatening to its neighbors to preclude cooperation on several issues (Kaye and Wehrey 2007).

The most recent but ineffective bid for regional leadership came from Turkey under its zero problems with neighbors policy. Inspired by Ahmet Davutoğlu’s Strategic Depth doctrine, Turkey embarked on a regional peace building policy couched in the language of liberal humanitarianism and soft power projection, which has received much criticism (Özkan 2014). Yet, this policy failed to gain sufficient international traction and succeeded only in causing a diplomatic crisis between Israel and Turkey. This was useful for Turkey’s domestic political purposes, but disagreements precluded the possibility of effective inter-state collaboration in alleviating the suffering of Palestinians (the original justification of the diplomatic incidence) and in allowing the latter government to conduct populism on “Arab Street.” None of these movements proved to be successful or provided the kind of impetus to advance a regional international society in the same way as the Treaty of Utrecht or the Congress of Vienna did for the European case.

State Level

The previous section highlighted the lack of a common vision for the Middle East and pointed out numerous bids for the privilege of articulating the interests of a Middle Eastern international society. Now a far more fundamental problem needs to be addressed; a point that also helps to explain the absence of regional great powers as well. Middle Eastern regimes are comparatively weaker than their counterparts elsewhere. The absence of a history of independent statehood, the lack of correspondence between borders and confessional preferences, and the unavailability of traditional state-building venues to Middle Eastern states have traditionally prevented the consolidation of most states (Jackson and James 1993). English school scholars often point out that it is worth studying European international society because its constituent members successfully spread overseas to assimilate otherwise disparate and isolated international societies formed around distant civilization cores (Buzan 2001, 484). This bloody and contested process eventually allowed European norms and practices, albeit with local variations, to shape aspects of other regional international societies, thereby helping to integrate them with the rest of the globe. What propelled European great powers to “success” was a combination of events, but most notably a competitive geopolitical environment that was favorable, especially in the nascent period of European international society, to war making and state-building (Tilly 1992, 1–3). War allowed powerful sovereigns to conquer territories, acquire wealth, build administrative and extractive capabilities, incorporate social classes into the state apparatus, and create unifying national ideas all the while extinguishing less effective and cohesive units (Tilly 1992, 24–25). Despite its long history of European-style war making, the sheer scale and organizational logic of the Ottoman Empire precluded the possibility of an effective, centralized imperial administration. Various Middle Eastern states had the opportunity to emulate the successes of European state-builders, but were eventually rebuked by external intervention (Lustick 1997). The only comparably cohesive states appear to be the ones that were former imperial powers themselves, or which successfully mobilized popular support against foreign occupation.

The state formation and consequent state transformation trajectory of Middle Eastern states also served to limit intraregional cooperation by creating inward-looking insecure regimes. This is an interesting counterpoint to regions like Latin America where states have also remained institutionally weak, and intra-state violence high due to the interests of regimes; but unlike the Middle East, inter-state peace and cooperation is remarkably robust (Centeno 2003; Martín 2006). Simply put, the antagonisms in state-society relations have led to regime insecurity in these states, therefore resulting in internally oriented security apparati (viz. Andreski 1980, 3–10; Ayoob 1996; Jackson 1990; David 1991; Barnett and Levy1991; Holsti 1996; Lustick 1997). One can posit, especially in the context of the Cold War, that conducting alliance politics with the view of defeating internal dissent and mobilizing public support for the regime was a higher security priority than making concessions in favor of a raison de système. However, this may not necessarily present an obstacle to the operation of an international society, because similar dynamics were in operation in European international society and arguably in Latin America’s international society as well. In the case of the former, in the 19th century, the Concert of Europe, comprised of reactionary monarchies that repressed progressive forces within European states, is a perfect example: a system established with the view of providing security to insecure states. Similarly, as in the case of Operation Cóndor Latin America provided political asylum to ostracized political leaders and their military establishments, also facilitated by the US, and often cooperated with each other to carry out domestic repression against threats to their regimes (Martín 2006, 167). Such solidarity has been absent in the Middle East as states have frequently aided violent non-state actors to undermine each other. An examination of sub-state actors in the Middle East may help reveal why such “solidarity” failed to manifest among Middle Eastern states even when some states faced challenges from similar sources, or of a similar kind.

Sub-State Level

The final implication for “order-weakness” in the Middle East is with regard to non-state actors. The divisions within Middle Eastern states and perennial state-weakness add layers of complexity, as international societies are less likely to thrive in the absence of sufficiently stable states capable of providing domestic order. The failure of the Middle East to establish regional order provides non-state actors with opportunities to pursue diverse and conflictive agendas that undermine regional international society. But before discussing non-state actors in the region, it may be useful to note that the English school traditionally advocates the functioning of international law and the “sacred” quality of sovereignty (Bull 1966; Jackson 1990). Respect for sovereignty, a recognition of the differences in the politics and aspirations of states in the pursuit of international order, is what makes an “anarchical society” possible. The classical, “pluralist,” understanding of international society argues for a stronger sense of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of states.

The English school also embraces the idea of humanity as being an inseparable part of “world society,” in which individuals and groups of states are the main referents, and notions of shared values and recognition of the broader interests of humanity are more important than states. “Solidarism” refers to a global fraternity of humanity that denounces efforts by states to impose order using force, and argues for the potential necessity of violating sovereignty for promoting normative ends such as justice and humanitarian causes. Of course, where an asymmetry of power is unavoidable, principles are usually abused. Powerful members of international society often set demanding expectations on its peripheral members and justify punishing them (Gong 1984; Stroikos 2014).

How do these concepts apply in the case of the Middle East? Non-state actors can, on the one hand, embody the normative aspirations of a regional international society and possibly the broader global world society. Many of these movements, for example the PKK, Hamas, and Hezbollah purport to pursue justice, either by acting on the right to self-determination, or as resistance against oppressors but are also considered to be terrorist actors by most states. Yet, they can also undermine international society because they challenge the basis for collective action by exacerbating regime insecurity, or simply by undermining functioning states. Without condoning violations of human rights, it must be said that great powers and regional powers alike have a proclivity towards justifying their interventions on lofty discourses of human rights. The First and Second Gulf Wars highlighted humanitarian sentiments in addition to broader global security concerns. Humanitarian concerns also animated the discussions concerning the 2011 intervention in Libya, and more recently, the debates surrounding Syria. In addition to being used for justifying interventions, non-state actors can become instruments of statecraft, as many have frequently been utilized as proxies by other regional and global powers to promote political and even economic goals. Iran’s role in supporting Hezbullah and Hafez Assad’s support for the PKK in the 1990s are example of how non-state actors can be used for power projection (Kirschner 2016).

The persistence of powerful non-state actors, violent or not, can undermine regional international society by incentivizing external and regional powers to act in self-regarding ways, which is ultimately detrimental to the regional society’s interests. This is not some unique dysfunction of Middle Eastern international society either, for non-state actors have historically operated either independently within international society or have been used as instruments of coercive statecraft to promote the raison d’état of states (Thompson 1996).

Some of the most important security challenges at the non-state level since the publication of International Society and the Middle East include state weakness in Iraq, economic and societal problems in the broader region instigating the “Arab Spring” and a Civil War in Syria, and most importantly, the emergence of ISIS. ISIS is a product of many of the cross-cutting problems in the Middle East and presents yet another challenge to regional order not only in terms of its contestation of established states and the overtly violent means with which it pursues its goals, but also its manifestation of the lack of a unifying and policy moderating vision of order in Middle Eastern international society.

ISIS operates, in many ways, just like the purveyors of private violence pursuing policies akin to state-builders, as was the case in early modern European history. For example, ISIS’s earlier activities in Iraq were likened by some to a “blitzkrieg” as ISIS fought across Iraqi territory and, like modern day privateers, looted the city of Mosul in summer 2014, including a branch of the Iraqi Central Bank. In other places of the world, such an audacious and effective operation by illicit entrepreneurs (terrorist or otherwise) would be unthinkable. The most interesting of ISIS’s functions pertain to its creation of economic networks to smuggle illicit goods as well as critical strategic resources such as oil. For countries with low resource endowments, the prospects of accessing oil well below market prices is too good an opportunity to pass up. In the case of ISIS, the methods are straightforward and low-tech. Once oil is extracted from wells and refined in boot-leg refineries, it could be disseminated for cheap domestic consumption (thanks to makeshift pipelines, among other means), or to the world market through “legitimate” actors (Giovanni et al 2014). In the case of Syria, there already was such a precedent, as much of its comparatively meagre oil production was used to (legally and illegally) procure foreign currency, even before the civil war. Previously, ISIS controlled oil fields in Northern Syria and Northern Iraq, and could sell oil below market prices through collusion with the governments in the region. Furthermore, the consumers include local sellers as well as representatives of oil companies (al-Khatteeb 2014). Interestingly, the smuggling activities were shared by many factions, including ones that ISIS is fighting against such as the Kurds, the Baghdad government, the Assad regime, and Turkey (Cohen 2014).

In this context, it may also sound unfair to suggest that such apparent dysfunctions are undermining Middle Eastern international society. There are, of course, reasons to believe that non-state violence should not be regarded as detrimental to international order per se. As the history of European international society and the eventual pacification of Mediterranean privateering attests, instability and uncertainty often help states to see the proverbial bigger picture (Colás 2016). The need of European powers to regulate private violence aided in the development of laws and practices, all of which ultimately contributed to the consolidation of European states, and therefore European international society (Thompson 1996, 3, 9; Colás 2016, 85). Despite the short-term interests of states and acts of collusion between states and ISIS during this conflict, there appears to be a general consensus among the great powers and regional states that ISIS is a threat to the regional order, even if earnest efforts against it have been slow to materialize.

A last point of concern in Middle Eastern international society is that of tragedies, such as the ongoing Syrian refugee crisis, which has forced over 11 million Syrians to flee their country since the beginning of the war. In a conflict that could have been mitigated at its onset, had it not been for the attitudes of powers interested in changing the Syrian regime, the heavy humanitarian toll could have been averted. However, the attempts by states to alleviate the crisis also merit guarded optimism not only about Middle Eastern international society, but also the global international society. Most notably, the countries neighboring Syria host nearly five million of these refugees, with Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan being the most active in this regard. Many others have been accepted by Western countries despite vituperative domestic debates. These efforts may be inadequate even with financial aid from regional and extra-regional powers, but it also shows the resilience of at least a modicum of humanitarian sentiments that is the cornerstone of any social or international order, be it a pluralist or solidarist one.

Conclusion

In attempting to discuss order and international society in the Middle East, this chapter has depicted a decidedly ambivalent picture. The number of extra-regional challenges and disunity among and within its constituent states, as well as a plethora of intra-regional challenges from violent non-state actors, cast doubts about the efficacy of Middle Eastern international society in delivering a tenable regional order. It is still in a state of flux in which power politics and threats confine the loci of states’ security interests to within their borders, and this further hampers the effective functioning of a regional society. In spite of this, historical precedence and some contemporary developments in tackling common threats and attempting to uphold normative practices also point to the indelible influence of a global international society and its humanitarian sentiments in moderating the collateral damage of unbound raison d’état behavior.

References

Al-Khatteeb, Luay. 2014. “How Iraq’s black market in oil funds ISIS,” CNN (August 22, 2014). Last Modified: October 20, 2017. http://edition.cnn.com/2014/08/18/business/al-khatteeb-isis-oil-iraq/.

Andreski, Stanislav. 1980. “On the Peaceful Disposition of Dictatorships,” Journal of Strategic Studies 3, no. 3 (January): 3–10.

Armstrong, David. 1993. Revolution and World Order: The Revolutionary State in International Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ayoob, Muhammed. 1996. “State-Making, State-Breaking and State Failure: Explaining the Roots of ‘Third World’ Insecurity.” In Between Development and Destruction: An Enquiry into the Causes of Conflict in Post-Colonial States edited by Luc van de Goor, Kumar Rupesinghe, and Paul Sciarone, 67–90. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bagge, Carsten and Ole Wæver, “In Defense of Religion: Sacred Referents of Securitization,” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 29, no. 3 (2000): 705–739.

Barnett, Michael N. and Jack S. Levy. 1991. “Domestic Sources of Alliances and Alignments: The Case of Egypt, 1962–1973.” International Organization 45, No. 3 (Summer): 369–395.

Black, Ian et al. 2016. “The Terrifying rise of Isis: $2bn in loot, online killings and an army on the run,” The Guardian (June 16, 2014). Last modified: November 20, 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/16/terrifying-rise-of-isis-iraq-executions

Bull, Hedley. 1966. “The Grotian Conception of International Society.” In Diplomatic Investigations: Essays in the Theory of International Politics, edited by Herbert Butterfield and Martin Wight, 51–73. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bull, Hedley. 1977. The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Buzan, Barry. 2001. “The English School: An Underexploited Resource.” Review of International Studies 27, no. 3 (July): 471–488. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026021050100471.

Buzan, Barry and Ole Wæver. 2003. Regions and Power: The Structure of International Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buzan, Barry. 2004. From International to World Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buzan, Barry and Ole Wæver. 2009. “Macrosecuritisation and Security Constellations: Reconsidering Scale in Securitisation.” Review of International Studies 35 (April): 253–276. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210509008511.

Centeno, Miguel A. 2003. Blood and Debt: War and the Nation-State in Latin America. Penn State Press.

Clark, Ian. 2011. Hegemony in International Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, David. 2014. “Remarks of Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence David S. Cohen at The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, “Attacking ISIS’s Financial Foundation,” US Department of the Treasury (October 23, 2014): http://kyleorton1991.wordpress.com/2014/03/24/assessing-the-evidence-of-collusion-between-the-assad-regime-and-the-wahhabi-jihadists-part-1/

Colas, Alejandro. 2016. “Barbary Coast in the Expansion of International Society: Piracy, Privateering, and Corsairing as Primary Institutions, Review of International Studies, 42, no. 5 (December): 840–857.

Costa-Buranelli, Filippo. 2015. “‘Do you know what I mean?’ ‘Not Exactly’: English School, Global International Society, and the Polsemy of Institutions,” Global Discourse, 5, no. 3 (July): 499–514.

David, Stephen R. 1991. “Explaining Third-World Alignment,” World Politics, 43, no. 2 (January): 233–256.

Davison, Roderick H. 1960. “Where is the Middle East?” International Affairs, 38, No. 4 (July): 665–675.

Giovanni, Janine di, Leah McGrath Goodman, and Damien Sharkov. 2014 “How Does ISIS Fund Its Reign of Terror?” Newsweek (October 6). Last modified April 20, 2017. http://www.newsweek.com/2014/11/14/how-does-isis-fund-its-reign-terror-282607.html.

Gong, Gerrit. 1984. The Standard of ‘Civilisation’ in International Society. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

González-Pelaèz, Ana. 2009. “The Primary Institutions of Middle Eastern International Society.” In International Society and the Middle East: English School Theory at the Regional Level edited by Barry Buzan and Ana González-Pelaèz, 92–117. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Halliday, Fred. 2009. “The Middle East and Conceptions of ‘International Society.’” In International Society and the Middle East, edited by Barry Buzan and González-Pelaèz, 1–23, New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Holsti, Kalevi J. 1996. The State, War, and the State of War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hurrell, Andrew. 2007. On Global Order: Power, Values, and the Constitution of International Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jackson, Robert H. 2000. The Global Covenant: Human Conduct in a World of States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jackson, Robert H. 1990. Quasi-States: Sovereignty, International Relations and the Third World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jackson, Robert H. and Alan James. 1993. States in a Changing World: A Contemporary Analysis Oxford: Claredon Press.

Kaufmann, Stuart, Richard Little, and William. C. Wohlforth. 2007. The Balance of Power in World History. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kaye, Dalia Dassa and Frederic M. Wehrey. 2007. “A Nuclear Iran: The Reactions of Neighbours,” Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, 49, no. 2 (June): 111–128.

Kirchner, Magdelena. 2016. Why States Rebel: Understanding State Sponsorship of Terrorism. Opladen: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Lustick, Robert. 1997. “The Absence of Middle Eastern Great Powers: Political ‘Backwardness’ in Historical Perspective.” International Organization, 51, no. 4 (Autumn): 653–683.

Mahan, Alfred T. 1902. The Persian Gulf and International Relations. London: Robert Theobald.

Malmvig, Helle. 2014. “Power, Identity and Securitisation in the Middle East: Regional after the Arab Uprisings,” Mediterranean Politics, 19, no. 1 (December): 145–148.

Martín, Felix E. 2006. The Militarist Peace: Conditions for War and Peace. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Özkan, Behlul. 2014. “Davutoglu and the Idea of Pan-Islamism.” Survival, 57 (July): 63–84.

Stroikos, Dimitrios. 2014. “Introduction: Rethinking the Standard(s) of Civilisation(s) in International Relations.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 42, No. 3 (August): 546–556.

Thompson, Janice E. 1996. Mercenaries, Pirates, and Sovereigns: State-Building and Extra-Territorial Violence in Early Modern Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tilly, Charles. 1992. Coercion and Capital: State-Formation in European History 990–1992. Blackwell.

Watson, Adam. 1990. “Systems of States,” Review of International Studies 16 (April): 99–109.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Political (In)Security in the Middle East

- Introducing the Major International Relations Theories

- Opinion – War in Ukraine: Why We Should Say No to International Civil Society

- Opinion – The Challenges Facing Joe Biden in the Middle East

- Opinion – The Risks of China’s Growing Influence in the Middle East

- Opinion – China’s Role in Mediating Middle East Crises