Since the 19th century, France has been the constant target of terrorism by various groups[1]. To counter this threat, regimes before the Fifth Republic had endorsed exceptional measures. The Fifth Republic is France’s current republican system of government; it was established by Charles de Gaulle under the Constitution of the Fifth Republic in 1958[2]. In 1963, under the Fifth Republic, la Cour de Sureté de l’Etat (the state security court) was created to try members of the Secret Army Organisation (OAS) after the Algerian war[3]. This measure aimed to judge in time of peace crimes and offenses affecting the internal and external state security such as espionage and terrorism but was made inactive in 1981. Therefore, until 1986 only ordinary courts tried crimes and offences against the interests of the nation. Since 1986, with the enactment of the law on the fight against terrorism and attacks on state security, terrorist cases have been entrusted to investigating magistrates or specialized prosecutors[4].

Terrorist incidents before the mid 1980s in France were not religiously inspired. The enactment of the first counter terrorism law in 1986 demonstrated that France had become a target of Islamist terrorism in the 1980s[5]. It has remained so ever since; as the gunmen attack on the Paris headquarters of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo on 7 January 2015 and the November 2015 Paris terrorist attacks (11/13 attacks) demonstrate[6]. Since 1986, French Parliament has never ceased to strengthen the legal arsenal against terrorism: no less than 20 counter terrorism measures have been implemented. After the 2015 attacks, France toughened its legal and security arsenal facing new and protean terrorist threats. Around 15 countermeasures had been adopted both after Charlie Hebdo and after 11/13 attacks, ranging from new doctrines of employment of the intervention forces to a new intelligence law giving more prominence to intelligence services[7]. Although these countermeasures have showed some success, the aim of this paper is to exhibit that they failed to meet challenges of current international terrorism.

This paper will be divided into four parts. Part I will analyze the counterterrorism measures adopted in the wake of the 2015 attacks. Part II will further examine the impact of the employed countermeasures and whether or not they had any counterproductive consequences. Part III will then provide some relevant countermeasures that were not used but might have proved to be more effective. This part will also analyze how success was defined and measured by French authorities. Lastly, Part IV will culminate the discussion by assessing what French counterterrorism measures are applicable for current counterterrorism operations.

Part I: A Forceful Counterterrorism Policy

Terrorist barbarism marked the year 2015. France witnessed the blind and cowardly violence of al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) followers[8]. Between January and November 2015, excluding the Charlie Hebdo and the 11/13 attacks, a dozen terrorist incidents occurred. On 7 January 2015, at about 11:30 local time, Saïd and Cherif Kouachi penetrated into Charlie Hebdo’s headquarters with assault rifles and murdered eleven people, including eight members of the editorial staff. Both perpetrators were killed two days later in in Dammartin-en-Goële – North of Paris- by members of the GIGN, the National Gendarmerie Intervention Group[9]. An accomplice of the Kouachi brothers, Amedy Coulibaly, murdered a municipal police officer on January 8 in Montrouge, south of Paris. The next day, he killed four Jewish individuals during a hostage scenario in a kosher supermarket in Vincennes.

The impact of this event was substantial for both France and countries abroad. The day after the attack, thousands of French people and foreign nationals claiming to be Charlie marched in the streets of Paris. On that same day, the French government announced its will to reinforce its counterterrorism arsenal. On the same occasion, several French politicians requested the establishment of the State of Emergency and demanded a French Patriot Act (similar to the US Patriot Act)[10]. On January 8, François Hollande, the French President announced the rise of plan Vigipirate’s alert levels. Vigipirate is France’s national security alert system, with three levels of threats: ‘vigilance’, ‘attack alert’ and ‘emergency attack’ Five days later, in complement to the Vigipirate plan, Operation Sentinelle was implemented as a means to reinforce security on the national territory. On July 2015, the French Parliament passed the Law on Intelligence. It allowed French intelligence services to monitor the communications of anyone linked to a terrorism investigation without the prior approval of a judge.

A few months later, on the evening of November 13, six attacks were perpetrated in Paris and in Saint-Denis[11]. Three explosions occurred at the Stade de France[12] in Saint-Denis, three shootings targeted terraces of Paris 10th district, one explosion detonated in a 10th district restaurant, and a mass killing targeted the Bataclan. Unlike the massacres perpetrated in the span of a few minutes on the terraces, the hostage-crisis after the Bataclan’s mass killing lasted several hours. The attack marked the first use of suicide terrorism on French soil: it killed 130 people and wounded 493[13].

On November 14th 2015, the Council of Ministers declared the State of Emergency. Although it had a period of validity of 12 days, it was extended and renewed 6 times. This special measure allows the Interior Minister and the Prefects[14] to take measures restricting freedoms on individuals whose activity jeopardizes national security and public order. The next day, a decree declaring three days of national mourning was published in tribute to the 11/13 victims. On November 16th, François Hollande brought together deputies and senators in Versailles where he made several announcements related to counterterrorism

Counterterrorism Measures

The French government adopted over a dozen measures in reaction to the 2015 attacks. These include among others:

- The Sentinelle military protection mission (January 2015): It mobilizes 10,000 soldiers aimed to strengthen security on the national territory.

- The law on Intelligence (June 2015): It gives more prominence to the intelligence services and allows eavesdropping and data recordings.

- Counter-radicalization programs focusing on the French prison system (2015): An additional 60 Muslim chaplains will join the 182 already serving in prisons and 5 areas dedicated to radicalized detainees.

- Law preventing the fight against incivilities and attacks on public safety and terrorist acts in the public transport of travelers: public transport network agents are allowed to conduct physical and baggage searches as well as visual inspections in a general and random manner.

- Creation of additional posts in the security forces (police, gendarmerie, customs and justice)

- Law reinforcing the fight against organized crime, terrorism and their financing, and improving the efficiency and guarantees of criminal proceedings (June 2016)[15]

- State of Emergency (November 2015): Declared in the night of 11/13 attacks, it grants law enforcement authority to search and seize terrorist suspects. Extended six times, it ended on November 1st

- Operation Chammal (2014): Although the airstrikes against ISIS had started in 2014, French air strikes intensified after 11/13.

- The deprivation of nationality for dual citizens: It aimed to expel dual-nationals who are deemed to pose a terrorist threat. Because the National Assembly and the Senate failed to reach an agreement, the project was abandoned[16].

Of the many measures that the French government implemented, five are particularly relevant. These five measures are the Sentinelle operation, the 2015 Law on Intelligence, the June 2016 law, the State of Emergency and operation Chammal.

Operation Sentinelle

Three days after the January 2015 attacks, the French Ministry of Defense (MOD) launched the military operation known as Operation Sentinelle[17] as a complement to the Vigipirate plan. The plan calls for specific security measures, such as increased police/military mixed patrols in subways, train stations and other vulnerable locations[18]. While the contribution of the army under Vigipirate amounted to just 800 soldiers on the eve of the attacks, with Sentinelle it rose to 10,000, including 6000 in the Paris region. Soldiers were responsible for the protection of 1400 sensitive locations including religious schools, places of worship, public transportation, government buildings, and media organizations. This measure was completed by the presence of 4700 police and gendarmes. The role of the army in Sentinelle was to protect and reassure French citizens; secure points and sensitive sites defined by the Ministry of the Interior; maximize the deterrent effect of the visible deployment of armed forces in the face of the terrorist threat[19].

The decision to activate Sentinelle was a strong political signal in understanding that the terrorist threat required a strong, determined and coherent response[20]. Considering that a replica attack was likely, it was vital to significantly strengthen the security of sensitive sites and to avoid the saturation of the internal security forces. Unlike internal security forces, which are necessarily spread over the whole territory, the French army has the possibility of mobilizing forces far superior in number. Thus, in this emergency situation, the added value of the armies appeared evident[21].

The Loi sur le Renseignement (The Law on Intelligence)

On 24th July 2015, French Parliament passed the so-called Law on Intelligence. Although the legislation project was accelerated after the Charlie Hebdo attacks, the project was not a direct consequence of the January attacks as it was designed in 2013[22].This law allowed French intelligence services to use new intelligence techniques. French intelligence services could only use two technical devices before this law. Security interceptions i.e. “wiretappings” relative to the secrecy of the correspondences sent by electronic communications. Intelligence services had also access to connection data, i.e. everything related to content of an exchange: telephone records, IP addresses, email recipients[23]. The 24th July Law implemented certain techniques already used by the police. These included the installation of beacons to locate in real-time a person, vehicle, or object: the capture of images, sounds, or computer data (if necessary with residential intrusion): the use of “local technical devices” that capture the connection data and in some cases the correspondence of mobile devices in their immediate environment[24].

These acts demonstrated the need to enable the early detection of terrorist projects and enhance the effectiveness of their prevention. Thus, the law also created two ways of exploiting the connection data in direct response to the attacks of January 2015. The law allowed intelligence services to track in real-time persons previously identified as presenting a terrorist threat through the collection of data connection. The legislation has had provisions to set up technical devices to identify suspicious behavior and identify new profiles, directly on the networks of telecommunications operators[25].

The Intelligence Act of 24th July defined for the first time an intelligence public policy. It contributed to the national security strategy as well as the defense and promotion of the fundamental interests of France. The missions of the intelligence services were specified for the first time. These provisions put an end to the absence of a normative framework to the activity of its intelligence services, which most Western democracies had already legislated.

Tools Offered by the Law of June 3, 2016

The law of June 3, 2016[26] toughened the law of 13 November 2014 aimed to strengthen the provisions relating to the fight against terrorism. The law of June 2016 introduced the following devices[27]:

- Online jihadist propaganda is a crime: Regularly consulting a site providing messages, images or representations directly leading to the commission of acts of terrorism for such acts is punishable by 2 years of imprisonment and a fine of €30,000. Extracting, reproducing or transmitting intentionally public apologizing or provoking acts of terrorism is punishable by 5 years’ imprisonment and a fine

- Baggage search and detention of persons: The law creates a legal framework for visual inspection and the search of baggage in all places with the authorization of the public prosecutor, operated by a police officer (OPJ) in the context of an identity check.

- New framework for the use of weapons for law enforcement: The police officers can incapacitate an armed individual who has committed several murders or attempts and who can legitimately be presumed to be preparing to commit others. The law provides that the police officer or the soldier deployed on the national territory is not criminally responsible.

- Fight against weapons offenses: The law broadened the tools for investigating arms trafficking. It hardened the conditions of acquisition and possession of weapons.

- A system of administrative control of returns on the national territory of persons who have joined terrorist groups abroad: This system may be applied for a maximum period of one month in respect of the assignment to remain at home or in a specific area, and six months in respect of the declaration of the domiciliation, the means of communication and displacements. Failure to comply with these restrictions is a criminal offense.

L’Etat d’Urgence (State of Emergency)

The creation of the State of Emergency in 1955 followed the wave of attacks perpetrated by the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) in November 1954[28]. In this context of instability, the government wanted to avoid declaring of the State of Siege because it granted all power to the military. Since 1955, the State of Emergency was decreed six times[29]. Yet, we are concerned here with the State of Emergency declared after the 11/13 attacks. In order to cope with an imminent threat whether as a result of a natural disaster, a health crisis, a conflict or, as is now the case, a wave of attacks, the state of emergency provisionally allowed the Minister of the Interior and Prefects an arsenal of powerful administrative measures[30]. These measures include searches, house arrests, prohibitions of stay, blocking of internet sites, to name a few. On 20th November, the law further extended the State of Emergency and strengthened its effectiveness. The text modified and expanded the system of house arrests. It also made possible administrative searches in public places and private places that are not homes or vehicles. The text also enabled the dissolution of associations or groups participating in acts that seriously threaten public order. As will be analyzed in the next part, the parliamentary commission of inquiry on the 11/13 attacks found that the State of Emergency was useful but limited and dwindling with time.

French Military Intervention in the Levant: Operation Chammal

France did not wait the 2015 attacks to combat terrorism outside its borders. Since September 2014, France has been part of the international coalition operations in Syria and Iraq[31]. Out of the 6500 soldiers deployed on other external theaters, 1300 soldiers from the Navy, Army and Airforce are taking part in the operation. This intervention serves three purposes: a security purpose, a purpose of stability and a purpose of credibility for France on the international scene. Being one of the elements in the fight against terrorism, this military operation fits a long-term strategy. In the wake of the January 2015 attacks, French airstrikes gained new momentum. Between 23rd February and 17th April 17 2015, the number of French fighter planes engaged in the operation tripled[32]. After the building up of intelligence on jihadist networks from Syria to France, Hollande decided in September 2015 to authorize reconnaissance flights over Syria and then to authorize strikes. After the 11/13 attacks, the French President decided to intensify the airstrikes in order to destroy ISIS. From 23rd November 2015, in support of the air strikes amplification, a carrier battle group was deployed for a second time. In 48 hours, six air raids were conducted from the aircraft carrier Charles-de-Gaulle destroying thirty-five targets.

Part II: A Long-fought Battle: Assessing the Impact of Employed Countermeasures

Sentinelle: A New Maginot line?

Although the added value of Sentinelle in securing the territory against terrorist attacks is often challenged, it has a psychological impact on the population[33]. In a climate of insecurity caused by the attacks, the presence of soldiers in train stations and tourists sites to name a few reassures the French population and/or foreign tourists. This reassuring effect is explained by the image of power of the armed forces in the streets. For instance, while the number of tourists in France had decreased after the 2015 attacks, since 2016 foreign tourists have returned, thanks in part to the presence of French soldiers[34]. Also, according to a poll executed by the French Ministry of Defense (MOD), 79% of French people approved of Operation Sentinelle[35].

The patrols’ ability to retaliate has been demonstrated several times since the deployment of soldiers on the national territory. On September 2017, a soldier was attacked by a man carrying a knife near the metro station of Châtelet-les Halles in Paris[36]. The threatened soldier with the rest of the patrol immediately controlled the offender. Additionally, on October 1st 2017, a man stabbed two women at the Saint-Charles Station in Marseille. A soldier retaliated and shot the individual. Similarly, on February 2017, an armed individual of Egyptian origin penetrated into the Louvre and attempted to attack a Sentinelle patrol. He was seriously injured by the police[37]. Although Sentinelle does not prevent attacks, it gives a real advantage for France’s security. For example, the individual might have killed other persons had it not been for the soldiers’ presence. The evidence of its value is that other countries like Great Britain, Italy, and Belgium have implemented the same system. Thus, removing it could be dangerous if nothing were to replace it.

Although these examples show the ability of soldiers to retaliate to attacks, it fails to show its deterrent effect. Since the implementation of Operation Sentinelle, soldiers have often been targeted by terrorists[38]. For instance, with static guards placed in sensitive sites, these sites become more visible and the soldiers are more vulnerable since they barely move and are dispersed in small teams. Because of this, since the 11/13 attacks, mobile patrols have been favored since these make soldiers’ movements less predictable. Yet, even when used in great numerical strengths and widely dispersed, ground forces were not able to protect all sites. Since January 2015, the soldiers have been targeted over a dozen times. For instance, on 20th April 2017, three French police officers were shot by French national Karim Cheurfi on the Champs-Elysees. French police Captain Xavier Jugelé, was killed.

The deployment of armed forces on national territory also has several counterproductive effects[39]. The setting up of Sentinelle after January 2015 was to last only a few weeks, but it has been continuously invoked for two years now. Although the added value of the army seems obvious in emergency situations, it is less so in the long run. The deployment of armed forces on national territory and on outside theaters creates a two-speed army. While one part of the army is deployed abroad to undertake more conventional tasks they are trained for, Sentinelle soldiers have very different modus operandi. This effects Sentinelle soldier’s capacity to operate in more conventional scenarios- patrolling in front of Eiffel Tower day-in day-out can hardly be a model for conducting operations in Mali[40]. Likewise, because Sentinelle represents one-third of the military deployments, the unit turnover rate was accelerated. Thus, French troops engaged in external theaters have no time for recreation nor to conduct various trainings. In order to reduce this pressure, it was necessary to withdraw soldiers from other operations. This explains why French troops are no longer deployed in Central Africa. Thus, Operation Sentinelle has had a direct impact on French armies’ overall effectiveness and morale[41].

A controversial Loi sur le Renseignement

Due to the classified nature of law’s results, it is difficult to deliver a comprehensive assessment of the techniques’ uses and therefore measure its successes[42]. Yet, according to a French National Assembly report, it seems that the intelligence services are beginning to take ownership of these new techniques and these techniques have already been the subject of applications for authorization. On 14th November 2017, more than two years after their appearance in law, the “black boxes”[43] have been activated. This device gives the French intelligence services a way to automatically analyze the metadata of Internet communications to detect a possible terrorist threat[44].

Despite the classified nature of the information, some data has been published. Overall, the law has allowed intelligence services to monitor more people. Between October 2015 and October 2016, at least 20,000 people were monitored by intelligence services, 47% of which were for terrorism prevention. Also, requests relating to terrorism cases have accelerated. Francis Delon, President of the National Commission for the Control of Intelligence Techniques (CNCTR) said the volume of demands regarding terrorism has become the first priority[45]. The CNCTR processed 48,208 requests between October 2015 and October 2016. This represented an increase of 14% if we compare the 42,274 requests in 2015. While these reports show how many people are under surveillance, it fails to show if these interceptions have thwarted terrorist attacks or led to terrorists’ captures.

The law has been criticized because it places greater emphasis on Technical Intelligence (TECHINT) at the expense of Human Intelligence (HUMINT). Had the media not overemphasized the technical aspect of the law, its HUMINT aspect would not have been concealed. The drafters of the law claimed that the text aimed for a proportionate increase of these two types of intelligence. Indeed, the report claimed that French Intelligence Chiefs share a mutual concern to promote HUMINT as well as TECHINT[46]. For instance, the installation of a technical device is useless without field work and vice versa because these two types of intelligence are intrinsic. Similarly, this law plans to create 490 posts for the three services responding to the MOD and aims to optimize the coordination of HUMINT and TECHINT.

The law’s investigative techniques significantly expand the number of people being under surveillance. For example, the text allows for surveillance of people who voluntarily or otherwise served as an intermediary to a person who is involved in a terrorist case. Jawad Bendaoud is known to have hosted Abdelamid Abbaoud, the November 2015 Paris attacks mastermind[47]. If the law had been operational then, Bendaoud could have been wiretapped and the police could have potentially had proof of his true role in the operation. Yet, if an innocent cab driver is wiretapped, it is a violation of his privacy. Likewise, ‘black boxes’ placed on the network of electronic communication operators will transmit data to identify data related to terrorism. Billions of data will be collected to identify the group of people who called an alleged terrorist. If data collected from this group of individuals among millions of people allows to thwart a terrorist attack, people have argued that the prevention of national security outweighs the violation of privacy[48].

Law of June 2016

It is too early to make a first assessment of the new administrative measures introduced by the Act of 3 June 2016. Yet, since November 2015, 271 French nationals have returned on French territory from Syria after being part of ISIS. Upon return, after being subject to administrative controls these so-called ‘returnees’ go through judicial proceedings and most of them go to jail[49].

Nonetheless, certain aspects of this law are subject to controversy. Individuals who have trained abroad with jihadist groups and suspected of being able to undermine public security on French territory may be placed under house arrest for one month. In addition, they will be required to communicate for several months the identifiers they use on the internet. The surveillance of these persons will result in an administrative decision and not from an “independent judicial judge”, which raises fears of arbitrary decisions. And according to a French MP, the monitoring of identifiers could be a heavy intrusion into the privacy of individuals, without any control[50].

The rules limiting the use of weapons by the police has also been withdrawn under this legislation. Gendarmes, police and customs officers are no longer be criminally liable if they fire in case of absolute necessity[51]. The idea is to allow the intervention forces to fire on the perpetrators of a terrorist attack, even if they are not in self-defense. On the one hand, it can be argued that this is a license to kill with a presumption of irresponsibility for the police. Yet, it could also apply in other cases than in terrorist attacks.

MPs voted the possibility for courts to pronounce a mandatory minimum sentence to perpetrators of terrorist crimes. It carries a period of up to 30 years, an increase from the previous 22 years. A court may also prohibit any measure of adjustment of the sentence. In addition, a mandatory security period is applicable for all terrorist offenses and crimes punishable by at least 10 years in prison. However, one can argue if an indefinite in prison sentence is actually the right way to punish individuals who want to die in suicide attacks.

State of Emergency: A Useful but Limited Contribution to Counterterrorism

The State of Emergency has been subject to criticism since its implementation. Certain civil rights associations and magistrates have denounced a decline in freedoms and in the rule of law. Yet, the implementation of the State of Emergency on the evening of 13th November was fully justified[52]. Because the perpetrators of these deadly attacks had not all been neutralized, there was a fear of other attacks. Thus an exceptional measure was needed at the time.

Nonetheless, there have been abuses that have resulted from the State of Emergency’s excessive security measures. Law enforcement officers have made searches in wrong places and arrested the wrong individuals. In one instance, elite policemen from the RAID[53] broke the door of a family apartment, crushed the father on the ground and injured a little girl. The police had targeted the wrong door, the neighbor was the target.

Measures of the State of Emergency have also had positive outcomes. Directed in the days following the 11/13 attacks, data published by the French Law Commission showed that police searches have had a destabilizing effect on the terrorist networks[54]. For instance, house arrests allowed to station individuals, hinder their movements, and their contacts outside, and the holding of meetings. From November 2015 to November 2016, more than 4000 searches were carried out in this context and 89 people were placed under house arrest[55]. According to the Chief of French Internal Intelligence services (DGSI), the searches destabilize terrorists and put them under an unprecedented pressure[56]. It is also an important element that justifies the state of emergency and the measures applied since its establishment. However, this destabilizing effect seems to have diminished rapidly. For instance, some radicalized individuals had emptied the whole content of their computer because they were aware of the measures in effect under the State of Emergency[57].

The State of Emergency also had few legal consequences. Defined as administrative measures likely to lead to the opening of incidental judicial procedures in the event of discovery of offenses, the administrative searches led to a limited number of judicial proceedings in the area of terrorism. The National Assembly report explains that targeted individuals could not be subject to judicial proceedings[58]. While intelligence services possessed information on individuals who had alleged links with terrorist networks, the lack of a material act prevented legal proceedings. After the State of Emergency, 31 terrorism-related offenses had been reported during administrative searches. These mainly concerned apology or provocation to terrorism such as the discovery of video messages or ISIS flags. On grounds of “criminal conspiracy in connection with a terrorist enterprise”, six judicial proceedings were initiated. These resulted in the seizure of the antiterrorist section of the Paris prosecutor’s office[59].

However, it would be reductive to evaluate the effectiveness of the State of Emergency to the number of terrorism-related judicial proceedings. Intelligence has probably been the main beneficiary of the searches. Administrative searches allowed intelligence services to know individuals better and to better understand the radicalization phenomenon. For instance, certain searches have allowed the services to learn more about terrorists’ means of communication[60].

Operation Chammal

The French military operation part of the international coalition strategy in Syria and Iraq has allowed to defeat and drive ISIS out of Syria and Iraq. Since the formation of the international coalition in 2014, ISIS has lost 95% of the territories it controlled in Iraq and Syria[61]. In 2016, ISIS still controlled 60% of its territory in Iraq. Raqqa has 300,000 inhabitants serving as a training ground for all terrorist groups operating in Syria. The loss of these sanctuaries is a very serious blow to the enemy every time. The terrorists’ ability to last, relies on the existence of sanctuaries because they are essential for them to train, to re-articulate and to stock up[62].

The death of French fighters in the Levant was a key objective for France’s internal security in preventing ‘returnees’ of committing terrorist attacks upon their return in France[63]. Syria and Iraq counted 3000 to 4000 European ISIS fighters, of which no less than a 1000 were French nationals[64]. Out of the 1000, about 265 French fighters have been killed and 271 returned to French territory, these returnees are either jailed or under surveillance. This leaves room for about 500 French nationals that could still be in the Levant or hiding somewhere else in Europe possibly planning to stage attacks in France.

However, this military setback does not mean the end of ISIS. The organization is now carrying out more asymmetrical actions such as suicide bombings and the use of improvised explosive devices (IED)[65]. If ISIS becomes isolated, the only options opened for the group may be to use terror techniques to attract new recruits. Eventually, attacks abroad may continue because the international coalition failed to defeat the groups’ ideology and thus its power to radicalize individuals. Without properly countering ISIS’s ideology, attacks like the one in Manchester or Berlin will only continue.

Part III: Proposals

The military forces included in Operation Sentinelle was meant to be active for a few weeks and then be replaced by police and gendarmerie forces[66]. In addition to the 4500 police and gendarmes, 2000 more would have been needed to keep Sentinelle working. With such a reinforcement, internal security forces would no longer need substantive support from the military to sustain the operation. The contribution of the military could be reduced to 1000 soldiers, as was the case before the January attacks. Gendarmes and police officers make a more effective Sentinelle operation because they are able to move very quickly from a position of public security to a posture of intervention. Along the same lines, there should have been a gradual decrease in the number of soldiers engaged in operation Sentinelle in order to solely focus on the protection of certain strategic points. It is an area in which the military have real expertise.

Furthermore, soldiers should be provided with handguns in addition to their allocated rifle and provided with training to use those handguns in closed environment[67]. The armed forces’ modes of action should be further adapted to their mission in the national territory[68]. In addition, the surveillance of certain places could be delegated to private security companies. This project was already initiated by the companies themselves, in particular through the proposals formulated by the Union of Private Security Companies (USP) on November 28, 2015. The state must be able to support them in order to strengthen them and associate these private companies more closely with the fight against terrorism[69].

Although the State of Emergency’s invoking was suggested by several French politicians to be implemented after Charlie Hebdo, Hollande only enforced it after the 11/13 attacks. Perhaps the French executive branch felt the level of terrorist threat was not high enough to justify emergency. Nonetheless, the 11/13 attacks brought an end to this wishful thinking. Some French officials have argued that the State of Emergency could have prevented the 11/13 attacks. Since November 2015, there have been 4469 administrative searches, 754 house arrest and 25,000 “fiche S”[70]. The “fiches S” cards are an indicator used by law enforcement to flag an individual considered to be a serious threat to France’s national security. However, it is almost impossible to know if the 11/13 attacks could have been thwarted by French Intelligence Services considering this terrorist operation was designed and organized from Syria[71]. Sponsors of the 11/13 attacks trained underground and have been able to evade the conventional forms of surveillance.

Since 2007 there have been considerable advances in the intelligence field, including various structural reforms and legislative and methodological developments. In 2008, President Sarkozy merged the Direction Centrale des Renseignements généraux (RG) and the Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire (DST) of the French National Police into the Directorate General of Internal Security (DGSI), France’s internal security agency. The RG was the intelligence service of the French Police and the DST was a domestic intelligence agency, responsible for the security of France against foreign threats and interference. The reform aimed to better monitor the Islamist threat. Nonetheless, it deprived France of its field network that could have been necessary to counter this jihadist threat. The current government should therefore create a new form of RG.

Both the January and November 2015 attacks have revealed communications flaws between the several intelligence services. Because they answer to different authorities such as the army and the police, there is a strong inter-service rivalry. For instance, the DGSI and the French External Intelligence Agency (DGSE) as well as the police and the gendarmerie have a history of strong infighting. Although it seems that following these attacks, exchange of intelligence regarding terrorism have improved, there is still a work in progress. Therefore, to address these gaps the government should create a national counter-terrorism agency responsible for threat analysis, strategic planning and operational coordination, directly attached to the Prime Minister or President[72]. The current French President Emmanuel Macron has created a counter-terrorism taskforce. According to the Elysée, it aims to strengthen coordination, to reinforce the management of the services engaged, and to organize a faster and more opened intelligence action between competent services against terrorism[73].

The June 2016 law created a prison intelligence service. Given the important role played by prison in the radicalization phenomena, it was necessary to strengthen the prison intelligence. Although there has been more recruitment of staff for this purpose, it still lacks the human, technical and financial means as well as a real doctrine to enable a professionalization of this service. It is therefore necessary to accelerate the recruitment and secondment of resources in order to create a fully operational office of penitentiary intelligence[74].

Assessing Metrics

The success of French counterterrorism policy after the 2015 attacks is mixed. The French government has compared the number of thwarted attacks since January 2015 with the period 1996-2012 to demonstrate the policy as a success story. From January 2015 to April 2016, intelligence services have thwarted 10 attacks[75]. Since 14 November 2015, 32 attacks plans were foiled[76]. Since January 2017, 13 attacks have been foiled. Between 1996 to 2012, one to two attacks were thwarted every year[77]. The year 2012 in France is a pivotal year in which we can see an increase in the terrorist threat level with the Mohammed Merah killing[78]. Jean Louis Bruguière, the former French anti-terrorist judge highlighted that in 2007, only 150 to 200 people were radicalized in France whereas in 2016 no less than 2000 to 3000 people are[79]. Thus, the number of people representing a danger have increased tenfold as well as the attacks thwarted.

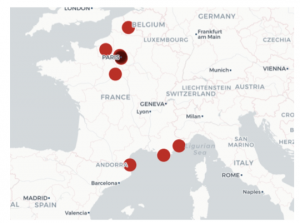

10 attacks thwarted in France from January 2015 until April 2016: seven attacks foiled in the North half of France and three attacks thwarted in the South of France. A famous foiled attack is the Thalys foiled attack. A carnage is avoided in a Thalys train linking Amsterdam to Paris when US military master a young Moroccan 25 years heavily armed that opens fire near Arras (close to the Belgium frontier)

Yet, these assurances provided by the French government are flawed when scrutinized. Although the number of foiled attacks seem comforting on the surface, it does not reveal the scale of the attacks. They could be small attacks targeting specific targets and killing a small number of people or have the magnitude of the 9/11 attacks where one day of attack killed thousands of people. The metrics showing the number of dead people reveal this flaw. From 1982 to 1995, 48 individuals died in terrorist attacks whereas since January 2015, 238 people died as a result of terrorism. While, on November 13 2015, more than 130 people died, which counts for almost half of the deaths, on 25th July 2016, a single priest was slaughtered.

These metrics do not seem to highlight other aspects of a counterterrorism policy that are possibly more important than just kinetic measures such as patrolling and boots on the ground. For example, Muslim population, assimilation, education, integration, teaching of valuable career skills in prison for returning fighters, etcetera have not really been emphasized. These non-kinetic measures are often more effective in countering terrorism.

Conclusion

Although it is often claimed that the 2015 attacks only revealed flaws in France’s counter-terrorism system, the attacks were a historical shipwreck. Hit by Islamist terrorism in the 1980s, France strengthened its counterterrorism policies to cope with the threat mostly by just passing legislation[80]. In the wake of the 2015 attacks, the French response mirrored the 1980s reaction. The catalog of legislation passed after 2015 listed at the beginning of this paper reveal this trend. For instance, the Kouachi brothers had been the subject of extensive surveillance by the intelligence services. The surveillance was finally interrupted because there was no evidence to establish a terrorist activity on the part of the Kouachi brothers. However, the surveillance of Saïd Kouachi illustrates a challenge of the new terrorist threat. Trained at discretion and mostly underground, foreign fighters have developed methods to foil classic forms of surveillance, even during long periods[81]. Some unsuccessful interceptions can thus constitute a clue to suppose that the person is hiding. Also, the intelligence services are always on the lookout and between the ministries, there is no real coordination. Even with new counterterrorism measures the problems that have existed for several decades resurfaced in 2015.

Furthermore, the French government should not have waited until the 11/13 attacks to implement the state of emergency. While the number of deaths in the Charlie Hebdo attacks were lower than the 11/13 attacks, the terrorist threat was still very high in January 2015. Likewise, the number of individuals marching in Paris on 11th January demonstrated the magnitude of the event. A tougher response is often needed even if the attack seems less substantial. The Belgian example illustrates this case. Two months before the Brussels attack, the Belgian authorities lowered the threat level to three on a scale of four. Although the threat level four probably would not have prevented the attack, it would have showed that government’s wariness[82].

The Constitution of the Fifth Republic promulgated in 1958 by General de Gaulle contains laws that allow the head of state to seize exceptional powers in the event of a major crisis[83]. These powers emanate from the weakness of the executive power of the Fourth Republic in response to the Algerian crisis and the German invasion. The State of Emergency is part of this logic. Thanks to this law, the executive branch was able to formulate a strong response to the November attacks. It would be interesting to apply this law in other countries as the latter has had positive effects on safety. Nonetheless, this method may not be transferable to other parts of the world because it would require to have a similar legal system. Also, for the measures to be accepted by the population, it is necessary that the measures are in line with the culture of the country. Also, invoking the State of Emergency in weak democracies might result in other problems such as rise in dictatorship.

Security justifies paying a price. This is what French citizens understood after the 2015 attacks. It is difficult to guarantee national security without infringing fundamental freedoms and the right to private life. Although the law on intelligence arguably violates privacy, the State of Emergency provoked excesses. The conundrum of balancing security with freedom has been a fundamental issue for governments throughout the ages. Is the surveillance of 10,000 French citizens to finally foil a minor terrorist attack worth the price of infringing people’s privacy/freedom? Similarly, an individual wandering the Champs-Elysées surrounded by soldiers in khaki uniforms may question his security rather than feel secure.

Endnotes

[1] Bonelli, Laurent. “Les caractéristiques de l’antiterrorisme français : “Parer les coups plutôt que panser les plaies” ”, in Au nom du 11 septembre…Les démocraties à l’épreuve de l’antiterrorisme. [Characteristics of French Counter-Terrorism : parry the blows rather than binding up the wounds] Paris, La Découverte, « Cahiers libres », 2008, p. 168-187. URL : https://www.cairn.info/au-nom-du–9782707153296-page-168.htm

[2] http://www.vie-publique.fr/decouverte-institutions/institutions/veme-republique/

[3] Frank Foley, Countering Terrorism in Britain and France : Institutions, Norms and Shadows of the Past. Cambridge University Press. March 2013

[4] Ibid

[5] Bonelli, Laurent. “Les caractéristiques de l’antiterrorisme français : “Parer les coups plutôt que panser les plaies” ”, in Au nom du 11 septembre…Les démocraties à l’épreuve de l’antiterrorisme. [Characteristics of French Counter-Terrorism : parry the blows rather than binding up the wounds] Paris, La Découverte, « Cahiers libres », 2008, p. 168-187. URL : https://www.cairn.info/au-nom-du–9782707153296-page-168.htm

[6] Hellmuth, Dorle. “Countering Jihadi Terrorists and Radicals the French Way”, in Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 38:12, 979-997 2015

[7] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en œuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[8] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[9] Ibid

[10] “Attaque de Charlie-Hebdo : Dupont-Aignan a proposé à Hollande d’instaurer l’état d’urgence” 20 Minutes avec AFP. 01.09.15 http://www.20minutes.fr/politique/1513467-20150109-attaque-charlie-hebdo-dupont-aignan-propose-hollande-instaurer-etat-urgence

[11] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[12] France’s National Stadium

[13] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[14] the State’s representative in a department or region

[15] LOI n° 2016-731 du 3 juin 2016 renforçant la lutte contre le crime organisé, le terrorisme et leur financement, et améliorant l’efficacité et les garanties de la procédure pénale. French Parliament https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000032627231&categorieLien=id

[16] Blavignat, Yohan. “Déchéance de nationalité : un abandon en six actes” Le Figaro. 03.30.2016 http://www.lefigaro.fr/politique/le-scan/2016/03/30/25001-20160330ARTFIG00296-decheance-de-nationalite-un-abandon-en-six-actes.php

[17] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[18] “Vigipirate : création du niveau urgence attentat”. [Vigipirate: creation of the level attack emergency] Le Parisien. 12.01.2016 http://www.leparisien.fr/faits-divers/vigipirate-creation-du-niveau-urgence-attentat-01-12-2016-6399408.php

[19] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[20] Ibid

[21] Ibid

[22] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[23] Ibid

[24] French Parliament. “LOI n° 2015-912 du 24 juillet 2015 relative au renseignement”

https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000030931899&categorieLien=id

[25] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[26] French Parliament “LOI n° 2016-731 du 3 juin 2016 renforçant la lutte contre le crime organisé, le terrorisme et leur financement, et améliorant l’efficacité et les garanties de la procédure pénale”. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000032627231&categorieLien=id

[27] French Interior Ministry. “Lutte-contre-le-terrorisme-les-avancees-grace-a-la-loi-du-3-juin-2016” [Fight against terrorism : advances thanks to June law 2016] https://www.interieur.gouv.fr/Archives/Archives-des-actualites/2016-Actualites/Lutte-contre-le-terrorisme-les-avancees-grace-a-la-loi-du-3-juin-2016

[28]Thénault, Sylvie “L’état d’urgence (1955-2005). De l’Algérie coloniale à la France contemporaine : destin d’une loi”, Le Mouvement Social, vol n°218, no.1,2007, pp. 63-78

[29] Ibid

[30] Thénault, Sylvie “L’état d’urgence (1955-2005). De l’Algérie colonial à la France contemporaine : destin d’une loi”, Le Mouvement Social, vol n°218, no.1,2007, pp. 63-78

[31] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[32] Ibid

[33] Egré Pascale & de Saint Saveur Charles. “Faut-il supprimer l’opération sentinelle ?” Le Parisien 08.10.2017 http://www.leparisien.fr/faits-divers/debat-faut-il-supprimer-l-operation-sentinelle-10-08-2017-7185321.php

[34] Ibid

[35] http://www.defense.gouv.fr/actualites/articles/les-chiffres-cles-des-sondages-de-la-defense-2015

[36] “Militaire attaqué à Châtelet-Les Halles : les policiers et soldats régulièrement pris pour cible depuis 2012” [Soldier attacked at Châtelet-Les Halles: police and soldiers regularly targeted since 2012] LCI https://www.lci.fr/faits-divers/militaire-de-sentinelle-attaque-a-paris-a-chatelet-les-halles-les-policiers-et-les-soldats-regulierement-pris-pour-cible-depuis-2012-2054410.html

[37] Llorca, Antoine. “Onze attentats déjoués en 2017 : de quels projets d’attaque parle Gérard Collomb ?” [Eleven attacks foiled in 2017: what plans of attack Gérard Collomb mentions?] LCI 09.08.2017 https://www.lci.fr/faits-divers/terrorisme-onze-attentats-dejoues-en-2017-de-quels-projets-d-attaque-parle-gerard-collomb-2062022.html

[38] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[39] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[40] Egré Pascale & de Saint Saveur Charles. “Faut-il supprimer l’opération sentinelle ?” Le Parisien 08.10.2017 http://www.leparisien.fr/faits-divers/debat-faut-il-supprimer-l-operation-sentinelle-10-08-2017-7185321.php

[41] Birnbaum, Michael. “Soldiers guard Europe’s street from terrorism, critics say that weakens them in war” The Washington Post. 12.04.2017 https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/soldiers-guard-europes-streets-from-terrorism-critics-say-that-weakens-them-in-war/2017/12/03/0312584e-b87a-11e7-9b93-b97043e57a22_story.html?utm_term=.b23ce45948d5

[42] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[43] Alonso, Pierre & Guiton Amaelle. “Surveillance : la première boîte noire est née” [Monitoring : the first black box was born]. Libération. 11.14.2017 http://www.liberation.fr/france/2017/11/14/surveillance-la-premiere-boite-noire-est-nee_160999

[44] Ibid

[45] Cabirol, Michel. “ Renseignement : plus de 20.000 personnes espionnées par les services en 2016”[Intelligence: more than 20,000 individuals spied by services in 2016] La Tribune. 12.13.2016 https://www.latribune.fr/entreprises-finance/industrie/aeronautique-defense/renseignement-plus-de-20-000-personnes-surveillees-par-les-services-en-2016-624046.html

[46] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[47] “13 novembre : Jawad le “logeur de Daesh” ne sera pas jugé pour terrorisme” [13 November: Jawad “ISIS’s host” will not be tried for terrorism] Valeurs Actuelles 07.11.2017 https://www.valeursactuelles.com/societe/13-novembre-jawad-le-logeur-de-daesh-ne-sera-pas-juge-pour-terrorisme-86251

[48] Ibid

[49] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[50] Hebert, Donald. “ Ce qui fait polémique dans le projet de loi urvoas contre le terrorisme” [ The controversial aspects of Urvoas’s counterterrorism bill] Nouvel Obs 03.03.2016 https://tempsreel.nouvelobs.com/politique/20160303.OBS5748/ce-qui-fait-polemique-dans-le-projet-de-loi-urvoas-contre-le-terrorisme.html

[51] Ibid

[52] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale P81

[53] Search, Assistance, Intervention, Deterrence

[54] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale P81

[55] “13 Novembre 2015 : comment la France a musclé sa politique anti-terroriste” [How France toughened its counter-terrorism arsenal since 13 November 2015]. BFM TV. 11.05.2016 http://www.bfmtv.com/societe/depuis-le-13-novembre-2015-la-france-a-muscle-sa-politique-antiterroriste-1055983.html

[56] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale P81

[57] Ibid

[58] Ibid

[59] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale P81

[60] Ibid

[61] “Les (rares) territoires encore contrôlés par Daech en Irak et en Syrie”. [The rare territory still controlled by ISIS in Syria and Iraq]. The Huffington Post 11.17.2017 http://www.huffingtonpost.fr/2017/11/17/les-rares-territoires-encore-controles-par-daech-en-irak-et-en-syrie_a_23280783/

[62] Ibid

[63] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[64] “Foreign Fighters: An Updated Assessment of the Flow of Foreign Fighters into Syria and Iraq”. The Soufan Group. December 2015 http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/TSG_ForeignFightersUpdate3.pdf

[65] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[66] Ibid

[67] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[68] Ibid

[69] Ibid

[70] Ibid

[71] Ibid

[72] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[73] Hausalter, Louis. “La “task force” anti-Daech de Macron, de la poudre de perlimpinpin ?” [Macron’s anti-ISIS task force: nothing but smoke and mirrors?] Marianne 06.08.2017 https://www.marianne.net/politique/antiterrorisme-la-task-force-anti-daech-de-macron-de-la-poudre-de-perlimpinpin

[74] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[75] Blavignat, Yohan. “Depuis Janvier 2015, la France déjoue un quasiment un attentat par mois” [Since January 2015, France has foiled almost one attack per month] Le Figaro 04.01.2016 http://www.lefigaro.fr/actualite-france/2016/04/01/01016-20160401ARTFIG00240-depuis-janvier-2015-la-france-dejoue-quasiment-un-attentat-par-mois.php

[76] French Ministry of the Interior “Sortie de l’Etat d’Urgence : un Bilan et des Chiffres Clés” Press information report on the State of Emergency

[77] “Entre 1996 et 2012, un à deux attentats déjoués par an en France” [Between 1996 and 2012, or to two attacks foiled each year] RTS Info 07.25.2016 https://www.rts.ch/info/monde/7899857–entre-1996-et-2012-un-a-deux-attentats-dejoues-par-an-en-france-.html

[78] Paolini, Esther & de Mareschal Edouard. “Terrorisme : de 2012 à 2017, la France durement éprouvée” [Terrorism: from 2012 to 2017, the hard-hit France] Le Figaro 10.01.2017 http://www.lefigaro.fr/actualite-france/2017/10/01/01016-20171001ARTFIG00134-terrorisme-de-2012-a-2017-la-france-durement-eprouvee.php

[79] “Entre 1996 et 2012, un à deux attentats déjoués par an en France” [Between 1996 and 2012, or to two attacks foiled each year] RTS Info 07.25.2016 https://www.rts.ch/info/monde/7899857–entre-1996-et-2012-un-a-deux-attentats-dejoues-par-an-en-france-.html

[80] Bonelli, Laurent. “Les caractéristiques de l’antiterrorisme français : “Parer les coups plutôt que panser les plaies” ”, in Au nom du 11 septembre…Les démocraties à l’épreuve de l’antiterrorisme. [Characteristics of French Counter-Terrorism : parry the blows rather than binding up the wounds] Paris, La Découverte, « Cahiers libres », 2008, p. 168-187. URL : https://www.cairn.info/au-nom-du–9782707153296-page-168.htm

[81] Fenech, G., & Pietrasanta, S. (2016) Commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en oeuvre par l’Etat pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (Rep. No. 3922) [Commission of Inquiry into the means implemented by the State to fight against terrorism since January 7, 2015]. Assemblée Nationale

[82] Maeterlinck, Nicolas. “Bruxelles abaisse d’un cran son niveau d’alerte face au terrorisme” [Brussels lowered by one notch its alert level to terrorism] RTS INFO 01.04.2016 https://www.rts.ch/info/monde/7383611-bruxelles-abaisse-d-un-cran-son-niveau-d-alerte-face-au-terrorisme.html

[83] Thénault, Sylvie “L’état d’urgence (1955-2005). De l’Algérie colonial à la France contemporaine : destin d’une loi”, Le Mouvement Social, vol n°218, no.1,2007, pp. 63-78

Written by: Jade Maillet-Contoz

Written at: Georgetown University

Written for: Dr. Bruce Hoffman

Date written: December 2017

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Terrorism as Controversy: The Shifting Definition of Terrorism in State Politics

- Terrorism as a Weapon of the Strong? A Postcolonial Analysis of Terrorism

- Institutionalised and Ideological Racism in the French Labour Market

- Liberal Democracies and Their Faulty Response to Terrorism

- Failed States and Terrorism: Engaging the Conventional Wisdom

- French Intervention in West Africa: Interests and Strategies (2013–2020)