This is an excerpt from Park Statue Politics: World War II Comfort Women Memorials in the United States. Get your free copy here.

Besides Korea, Taiwan is the only country that was annexed by Japan in the period leading up to WWII. Taiwanese and Koreans shared the experience of Japanese colonial rule. When one visits Taiwan, one discovers a more positive and appreciative attitude towards Japan than one finds in Korea, which does not conceal its deep feelings of resentment. Although no doubt much less in number, Taiwanese comfort women, like their Korean counterparts, were forced to provide sexual services to Japan’s military. Nevertheless, while 38 statues and monuments honor the memory of the comfort women throughout Korea, not one such statue can be found in Taiwan. Unlike Korea, Taiwan has erected monuments to pay homage to Japan, honoring the contribution that Japanese made to Taiwan during the colonial period.

Taipei opened its first comfort women museum in December 2016. The museum clearly points to Japan’s culpability for the comfort women system. It further goes on to suggest practical ways that the comfort women ordeal can inform today’s efforts to end human trafficking and domestic violence in Taiwan, crimes which stem from a demeaning view of women.

In May 2016 when President Tsai Ing-wen was inaugurated as Taiwan’s president, members of her Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) called upon her to rethink how Taiwan remembers the Republic of China’s founding president Chiang Kai-shek. A debate has surged about whether or not to demolish or repurpose the spacious park grounds, facilities, and museum in downtown Taipei that currently celebrate Chiang Kai-shek’s achievements.[1] In the spring of 2017, three public statues of Chiang were vandalized and decapitated.[2]

While Chiang is viewed critically, some of the Japanese who lived in Taiwan during the colonial period are fondly remembered. In the city of Tainan, there is an annual ceremony to celebrate the life of Japanese civil servant Yoichi Hatta. The Taiwanese participants in the ceremony offer flowers and deep bows to Hatta’s statue in the park, paying homage to his role in turning “the infertile land of southern Taiwan into an abundant ‘rice barn.'”[3]

The Taiwanese recognize Japan’s role in the development of Taiwan’s trained workforce, in the modernization of its irrigation systems, in the building of the Taiwanese railway system,[4] and in the design and creation of many of Taiwan’s major government buildings.[5] The favorable recollections that most Taiwanese harbor towards the period under Japanese rule help to explain their reservations toward criticizing Japan for its callous mishandling of the comfort women issue. Any such campaign, they fear, could destabilize the greatly valued bilateral ties that Taiwan holds with Japan.

Japan’s Annexation of Korea and Taiwan

In the final decade of the nineteenth century, Japan had its eyes set on becoming an imperial power like France, England, and Holland. Japan modernized its military, including its naval forces, in the years following the March 31, 1854 Convention of Kanagawa between U.S. Commodore Matthew Perry and the ruling Tokugawa shogunate. Following the first Sino-Japanese War in 1895, which took place primarily over Japan’s efforts to gain control of Korea, Taiwan was ceded to Japan by China’s ruling Qing Dynasty through the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki.

Korea sought out Russian support to avoid falling under Japanese control, leading to the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. Once again, Japan prevailed, and, following the Treaty of Portsmouth (New Hampshire), Japan felt supported by the United States in its efforts to gain control of Korea. In 1905, through the Eulsa Treaty of Protection, Korea fell largely under Japan’s control and was fully annexed in 1910. Japan later recognized the inhabitants of Korea and Taiwan as subjects of Japan and granted them citizenship. Because they were subjects of Japan, Taiwanese and Korean comfort women were viewed differently than the women taken by the Japanese military in places such as the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, or China. The latter groups were seen as the “spoils of war” as opposed to an auxiliary force to the Japanese military who were performing an important patriotic duty.

Taiwan’s versus Korea’s Experience of Japanese Colonial Rule

In spite of both Korea and Taiwan having been Japanese colonies and both having had women conscripted as comfort women, Taiwan’s historical memory of the period under Japan contrasts with Korea’s. Taiwan was Japan’s first colony, acquired in 1895, 15 years prior to Japan’s full annexation of Korea. Japan’s leadership considered success in its colonization efforts in Taiwan as key in gaining recognition from the West that Japan had indeed “arrived” as an imperial power.[6] Japan wanted to demonstrate that it could not only govern as an imperial power, but that it could actually improve the living conditions of the inhabitants of its colonies.[7] Japan played a major role in modernizing Taiwan and promoted local self-rule by the Taiwanese. Japan also contributed to Korea’s modernization and to local self-rule; however, the period in Taiwan after war under Chiang Kai-shek is seen by most Taiwanese as a second, more oppressive colonial period than the years under Japanese rule.

The Taiwan Experience under Japan

When Taiwan was ceded to Japan in 1895 through the Treaty of Shimonoseki, local Taiwanese leaders at first made an effort to establish an independent Republic of Formosa and resist annexation. Some level of local resistance to Japan’s annexation of Taiwan continued for decades. The Tapani Incident of 1915 and the Wushe Uprising of 1930 stand as the most remembered acts of Taiwanese resistance to Japanese rule. In 1915, Taiwanese locals of Han Chinese origin, affiliated with a local Buddhist sect, carried out a series of “armed attacks against police stations;” the Japanese crackdown that followed resulted in the deaths of some 1,412 Taiwanese of Han Chinese origin and “another 1,424 were arrested and sentenced by the Japanese colonial government.”[8] The Tapani Incident represented the final major armed revolt against Japanese rule led by Taiwanese of Han origin.

The 1930 Wushe Uprising was led by the Seediqs, one of Taiwan’s aboriginal tribes. In October 1930 the Japanese district governor came to officiate over Wushe’s annual sports competition accompanied by scores of other Japanese military and civilians. An armed contingent of “300 aboriginal men in native attire and armed with rifles, guns, and swords” attacked the Japanese delegation, killing 134 of them, including not only the Japanese police commissioner and soldiers who participated but Japanese civilians as well, including women and children. In response, the Japanese mobilized some 3,000 troops. They killed 214 Seediq warriors and their family members.[9]

The Japanese military leaders who presided over the Wushe crackdown received harsh reprimands from the government of Japan. Japan had hoped to be recognized for improving the well-being of its colonies rather than for repressing them. After the Wushe uprising, Japan adopted new policies aimed at treating Taiwan’s aboriginal population with greater respect, “as imperial subjects assimilated into the Japanese national polity through the expressions of their loyalty to the emperor”[10]

Rule under Japan versus Rule under Chiang Kai-shek

Koreans understandably harbor deep, unsettled feelings of resentment due to Japan’s failure to openly accept responsibility and fully apologize for their actions during the colonial period. They can point to Japan’s brutal torture and execution of Korean independence leaders, to the persecution of Korean Christians who objected to emperor worship, to the suppression of the Korean language and culture, to the confiscation of Korean families’ food supplies, and to the forced mobilization of Koreans as slave laborers, soldiers, and comfort women.[11] Although the Taiwanese had memories such as Tapani and Wushe, their historical memory of suffering under Japan softened due to what the island experienced after its “liberation” following WWII by the Kuomintang (KMT) forces of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.

In August 1945 the island’s inhabitants, including the Han Chinese whose family ties to Taiwan, which in most cases traced back centuries, celebrated the end of five decades of Japanese occupation; however, this elation soured soon after the arrival of Chiang’s KMT representatives. Dispatched to accept the surrender of Japan’s occupying army, they showed little patience for Taiwanese resistance. A ruthless crackdown began on February 28, 1947, an event referred to as the “February 28 Incident” or the “228 Incident.” One day prior on February 27, KMT security forces apprehended and publicly interrogated Ms. Lin Jiang-mai, a 40-year-old widow, for allegedly selling contraband cigarettes at her vending stand in Taipei. The KMT security forces seized both her contraband product as well as her inventory of government-sanctioned cigarettes. They also impounded the earnings from her sales. When Ms. Lin protested, she was struck on the head with a gun by KMT security forces.[12]

Her pleas for mercy attracted a sympathetic local crowd and sparked their indignation. Intimidated by the crowd’s outcry, the KMT forces fled the scene but not before firing into the crowd, killing one person. This led to nationwide protests the following day, calling for the arrest and punishment of the persons responsible for the previous day’s shooting. The KMT reacted callously, killing an estimated 18,000 to 28,000 Taiwanese protesters and activists over the next few weeks. The 228 Incident and its aftermath provided the KMT with a rationale for implementing the 38 years of martial law that followed, commonly referred to as the “White Terror.” With the 1949 collapse of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nanjing government, forcing his flight to Taipei, the KMT further tightened its grip. Furthermore, for the next two decades, Taipei would serve as the de facto capital of what the United Nations would recognize as “China” until the Beijing government assumed the UN seat on October 25, 1971.

The four-decade long period of White Terror repression under Chiang Kai-shek and then his son Chiang Qing-kuo stifled political dissent and any effort for Taiwanese independence. Violations of the stringent limitations imposed on speech and assembly by the Chiangs resulted in severe reprisals.[13] Grandparents, parents, other close relatives, as well as friends of many of today’s Taiwanese endured imprisonment and torture between 1949 and 1987. The accounts of the KMT’s punitive and vindictive comportment during this period help to explain why today most Taiwanese have developed an increasingly benign view of Japanese colonial rule compared to the experience under Chiang Kai-shek and his son.

In 1997 President Lee Teng-hui, the first Taiwanese native to serve as president of Taiwan, inaugurated the 228 Museum. It serves as a constant reminder that KMT rule led to tens of thousands of Taiwanese being subjected to arrests and torture including at least 1,200 summary executions.[14] Past authoritarian KMT rule, along with Beijing’s persistent, strident calls for “One China” and Beijing’s own repressive history help to explain the positions taken by recent independence-minded CSOs in Taiwan, including the youth-led Sunflower Movement, which in 2015 spearheaded calls for Taiwanese de jure independence from the mainland.[15] Mainland China, in spite of its criticism of Chiang Kai-shek, has not endeared itself to Taiwan. For some, the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown by Beijing revived haunting memories of the 228 incident.[16] The Taipei Times as well as a number of other Taiwanese publications report that the PRC detains not only human rights activists but the attorneys who dare to defend them. [17]

One popular Taiwanese saying describes the change from Japanese to KMT rule in Taiwan as “the dogs (the Japanese) left but the pigs (KMT) came.”[18] Taiwanese history professor Lung-chih Chang explains that “dog,” which is used here to represent Japan, implies tight control and repression but that, in spite of this, the dog’s “discipline” leads to order and predictability. On the other hand, the “pig,” depicting KMT rule, is also characterized by force and repression; however, rule by “pigs” does not result in the same order and predictability that one finds when ruled by “dogs.”[19] The accommodating recollections that most Taiwanese now harbor towards their period under Japanese rule explain why many Taiwanese prefer to downplay the need for Japan to accept responsibility, offer an official apology and compensate the few surviving Taiwanese victims. Such an approach, they fear, would destabilize bilateral ties.

A dissenting view on Japanese colonization of Taiwan, nevertheless, finds unsettling ways of expression. On April 17, 2017, Lee Cheng-lung, a former Taipei City Councilor and an activist in Taiwan’s small China Unification Promotion Party, along with an accomplice, took the extraordinary step of decapitating the Yoichi Hatta statue in Tainan. Lee boasted of his actions on Facebook and turned himself in to police in Taipei. However, he refused to reveal where he had hidden the statue’s missing head. [20] Tainan city officials acted quickly repaired the damaged statue. On May 7 Tainan Mayor William Lai, together with members of the Hatta family, participated in a rededication ceremony. Lai “apologized to the Hatta family for the city’s failure to protect the statue,” and, with heightened security, the restored statue was ready on schedule for the annual May 8 ceremony honoring Hatta.[21] On April 22, just five days after the Hatta incident, a statue of Chiang Kai-shek was decapitated in a park “on the outskirts of Taipei.” Red paint was dumped on both the statue and the decapitated head. “228” was spray-painted on the statue base.[22]

Taiwan’s Resistance to Partnership with Beijing on the Comfort Women Issue

In October 2016, China unveiled a sculpture at Shanghai Normal University commemorating Chinese comfort women.[23] Beijing has recently demonstrated a growing interest in promoting the comfort women cause and reminding the world of the crimes committed by Japan during the 1930s and 1940s. Their efforts have been reinforced by some Chinese and Chinese-Americans in the United States. [24] A state dedicated in Seoul in October 2015 portrays a Korean comfort woman and a Chinese comfort woman seated beside each other. The South Koreans who organized the ceremony told the New York Times that “they planned to build replicas of the same sculpture in Shanghai and San Francisco.” In explaining the basis of China’s bond with Koreans, Leo Shi Young, a Chinese-American filmmaker and key supporter of the project, noted that “Koreans and Chinese resisted together like brothers against Japanese aggressions.” [25]

Too firm an alliance with Korea, because of its strong ties with mainland China on the comfort women issue, is not a prudent option for Taiwan. It could undermine long-term Taiwanese political interests in remaining separate from China. Taiwan needs lasting, positive ties with Japan. Taiwanese citizens do not wish to be seen as Chinese nationals or as outliers destined to join the PRC.

The Comfort Women Experience in Taiwan

In her interviews with Taiwanese comfort women, Dr. Chu Te-lan, a senior researcher in Academia Sinica’s Research Center for the Humanities and Social Sciences and recognized authority on Taiwan’s comfort women, found that only three of the women whom she interviewed understood at the time of their conscription that they would serve as sex workers.

The other comfort women interviewed by Chu stated that they had been misled by recruiters, just as most Korean comfort women had been deceived by their handlers’ false promises.[26] Taiwan’s victims had received assurances that they would serve as entertainers, barmaids, office workers, and nurses[27] but certainly not as sex workers. Their deceptions in recruitment mirror those of most Korean comfort women.

In spite of parallel testimonies on recruitment, the estimated number of Korean women recruited into the comfort women system greatly outnumbers Taiwanese women. Chu estimates only 1,000 women in Taiwan were conscripted,[28] whereas the Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation (TWRF) estimates at least 2,000 women.[29] Both of these figures “pale” in comparison to the tens of thousands of Korean women and girls thought to have been conscripted.[30]

Navigating between Tokyo and Beijing: Lessons from the Ama Museum

Based on the definitive evidence of Taiwanese comfort women provided by Ms. Itoh Hideko, followed by the first Taiwanese women coming forward and identifying themselves as former comfort women, Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan established a Taiwanese Comfort Women Investigation Committee in 1992. One outcome of their deliberations was to delegate the Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation (TWRF), a local Taipei NGO, as the sole “focal point for efforts to solve the comfort women issue in Taiwan,” assigning it the responsibility to: “1. identify former comfort women; 2. handle information on individuals; and 3. act as an agent in transmitting to them government subsidies for their living expenses.”[31]

Through a documentary history of Taiwan’s comfort women that TWRF released in 2005 entitled Silent Scars: History of Sexual Slavery by the Japanese Military – A Pictorial Book (2005),[32] TWRF, like its counterpart the Korean Council, strongly criticized Japan for failing to accept responsibility for the comfort women system and its cruel and inhumane treatment of the system’s victims:

When will Japan bear its responsibility as Germany had done? We demand that Japan, forever flaunting the image of a civilized nation, honestly accept its responsibility and act expeditiously to win back trust and respect from the international community.[33]

At other times as well, TWRF has been equally critical. In 1995 when Japan’s quasi-official AWF proposed a ¥2 million (approximately $18,000) “atonement” payment to every surviving comfort woman, TWRF joined the Korean Council in opposing this. Because neither the acceptance of responsibility nor the proposed payments were from official government sources, TWRF maintained that “not a single Taiwanese victim accepted the ‘compensation’ from the Asian Women’s Fund.” For its part, the Taiwanese government itself provided a payment of an equivalent amount to each surviving Taiwanese comfort woman.[34] It also extended a monthly subsidy of $15,000 TWD (Taiwanese Dollars), approximately $550 U.S. Dollars, to each of the two surviving women.[35] The funds were described as an advance to the women by the Taiwanese government. The government anticipated that these funds would eventually be returned to Taiwan by Japan once a final settlement was reached.[36] In addition to Taiwanese government funds, individual donors in Taiwan also provided support to the victims.[37] Immediately after the ill-fated December 28, 2015 settlement between the governments of Korea and Japan, Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou called upon Japan to not limit itself to Korea, but to also address the case of Taiwan’s comfort women through a similar official apology and compensation.[38]

Some statements in TWRF’s Silent Scars: History of Sexual Slavery by the Japanese Military – A Pictorial Book caused the organization to be viewed as a tool of the KMT, due to making public the Taiwanese who had collaborated with the Japanese government. It described how some Taiwanese and Koreans had done the bidding of the Japanese military by rounding up comfort women:

While Japanese amnesia has sought to wipe out comfort women, Japan’s Asian neighbors in some cases, may have failed to look inward. A number of abductors of comfort women were Korean and Taiwanese. [39]

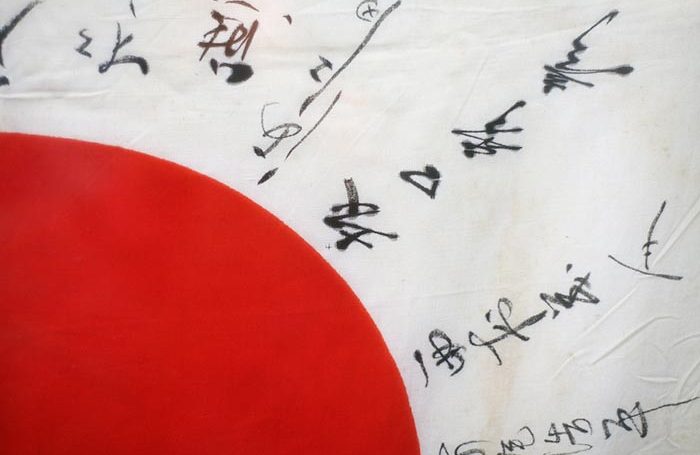

TWRF also portrayed President Li Teng-hui, Taiwan’s first native-born Taiwanese President, as “pro-Japanese,” pointing out that he “flaunted his defiance of anti-Japanese Taiwanese by posing as a samurai in one notorious photograph.”[40]

Today the TWRF has new, younger leadership who recognize that efforts to memorialize and seek justice for Taiwan’s comfort women require more finesse than frontal assaults on Japan. TWRF’s Executive Director Kang Shu-hua, who holds a master’s degree in Social Work from Columbia University, has learned to detect and navigate the landmines of Taiwan’s political and diplomatic landscape. She understands that most Taiwanese rely on Japan’s support to retain, as 96% of the citizens of Taiwan wish,[41] a political identity and trajectory independent from China’s.

Cultural, humanitarian, and defense partnerships serve to deepen and preserve bilateral relations with Japan, which remains Taiwan’s second largest trading partner.[42] Prime Minister Abe, frustrated by Beijing’s ongoing ventures in military brinkmanship, has sent signals that Japan could opt to use force if China initiated military operations against Taiwan.[43] That statement of support alone might explain why 65% of Taiwanese either feel “close or very close” to Japan[44] and why TWRF’s past strident attacks on sympathetic views towards Japan have been curtailed.

In an October 2016, Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History resident senior scholar, Dr. Shiu Wen-Tang, and I met with the TWRF Executive Director Kang Shu-hua,[45] who elaborated on ways in which the handling of the comfort women issue in Taiwan remains politically sensitive. When we inquired about whether TWRF might set up a comfort women statue near the new Ama Museum for Taiwan’s comfort women, one of her staff members confided that overseas groups had offered to fund such a statue but that TWRF declined to accept. TWRF representatives expressed concern that the statue would provoke a backlash, including the possible defacement of the statue by pro-Japan Taiwanese groups who would view this as a calculated “impairment” of Japan’s “dignity.”[46]

In October 2015, Taiwanese President and KMT party leader Ma Ying-jeou called upon citizens of Taiwan to first remember the good that Japan had done for Taiwan “while not forgetting the bad.”[47] TWRF obviously does not forget the bad. At the same time, unlike the Korean Council, TWRF has a broader institutional mandate than the comfort women issue. Prior to being chosen by Taiwan’s legislative Yuan to oversee comfort women matters in Taiwan, TWRF, which was founded in 1987, focused on addressing childhood prostitution and assisting its victims. When it assumed responsibility in 1992 for seeking justice for Taiwan’s comfort women, the TWRF chose not to abandon its work with children. It views the comfort women experience as a resource to inform TWRF work in its other areas of activity.[48]

TWRF committed itself to establishing a site to commemorate Taiwan’s comfort women in 2004.[49] It finally opened the Ama (Grandmother) Museum in December 2016 after many challenges. The Museum has two exhibition halls. The first hall displays photos and images that convey information about the comfort women system that Japan created. It exposes its depravity and the suffering that the women endured and the “trauma faced by survivors.” [50] The survivors, nevertheless, are “the stars of the show” and are “cast not as the powerless victims of a monumental atrocity, but instead as leading figures in their own human rights struggle,” that is, the struggle to press the Japanese government for an official apology and compensation.[51] This pursuit of redress is the theme of the museum’s second exhibition hall. It depicts the survivors “leading protest marches or attending legal proceedings in Japan.”[52] Kang explains: “These victims want their reputation and dignity to be restored. That can only arise from the Japanese government adopting a truly reflective attitude on this topic.”[53]

The TWRF website also depicts the full lives of the comfort women, both their suffering and their triumphs, including their participation in a variety of cultural activities including art and dance.[54] TWRF has worked, Kang observes, to help the former comfort women to gain the confidence to “stand up for themselves and find their voice.” [55] When the first comfort women came forward, they spoke from behind a curtain; that initial reserve changed as they found and learned to support each other. Kang compares the comfort women to today’s victims of sexual and domestic violence that TWRF supports: “A lot of people are just like these Ama in that they don’t want society to know what happened to them.” She adds, “So we think that through the courage and strength of these Ama, we can encourage others to speak up.”[56]

Keith Menconi, an independent journalist and radio host in Taiwan, did report on the Museum in April 2017. His visit led him to conclude that “the real aim of the Ama Museum is to humanize the survivors and draw attention to their lifetime of resilience.[57] TWRF’s approach calls upon visitors to consider what this past history “has to do with their lives and the world we are living in today.”[58] It could have applications for Korean and Korean-American supporters of the comfort women cause. Korean and Korean-American organizations tend to focus largely, if not exclusively, on memorializing the comfort women’s tragic suffering and on Japan’s culpability in creating the comfort women system. However, they do not stress how the comfort women coming forward can encourage today’s victims of human trafficking and domestic violence to come forward as well. Ironically, still today Korea[59] and Japan[60] number among the developed countries that fare worst in addressing domestic violence. These two countries are also cited for ongoing major involvement in human trafficking. [61] [62]

In the Taiwan equation for survival, close ties with Japan remain a critical component. The current Taiwanese government and TWRF can thus be expected to continue to address the comfort women issue with more deference to Japan than in Korea. Statements of support for Taiwan by Japan’s Prime Minister Abe, including his bold April 2013 decision to support the sharing of fishing rights with Taiwan around the disputed Senkaku Islands[63] and his deliberate reference to Taiwan in his April 2015 speech to a Joint Session of the United States Congress,[64] afford Taiwan a needed morale boost and political leverage for the present and the near future. While some harbor grievances related to Taiwan’s colonial past, the vast majority of Taiwanese have gone beyond those sentiments.[65] Unlike China and Korea, they refuse to allow Taiwan’s comfort women issue to metamorphose into “a righteous battle against Japan.”[66]

Notes

[1] “Leave Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall Alone,” China Morning Post, May 6, 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20160511181648/http://www.chinapost.com.tw/editorial/taiwan-issues/2016/05/06/465247/leave-chiang.htm.

[2] Hideshi Nishimoto, “Chiang Kai-shek Statue Beheaded in Taiwan in Latest Incident,” Asahi Shimbun, April 23, 2017, http://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/AJ201704230023.html.

[3] Chiu Yu-tzu, “Japanese Pioneer Remembered,” Taipei Times, May 5, 2000, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/local/archives/2000/05/05/34805.

[4] “Railway Diplomacy,” Taiwan Today, May 1, 2015, http://taiwantoday.tw/news.php?unit=8,29,32&post=14202.

[5] “Taiwan President Says Should Remember Good Things Japan Did,” Reuters, October 25, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-taiwan-china-idUSKCN0SJ03Y20151025.

[6] Leo T. S. Ching, Becoming ‘Japanese:‘ Colonial Taiwan and the Politics of Identity Formation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 17.

[7] Ching, Becoming ‘Japanese:‘ Colonial Taiwan and the Politics of Identity Formation.

[8] Tapani Incident Centennial Marked by Tainan City,” Taiwan Today, June 9, 2015, https://taiwantoday.tw/news.php?unit=2&post=3673.

[9] Ching, Becoming ‘Japanese,’ 138-139

[10] Ching, Becoming ‘Japanese,’ 152.

[11] Michael Breen, The Koreans: Who They Are, What They Want, Where Their Future Lies (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2004), 103–115.

[12] Flora Wang, “The 228 Incident: Sixty Years on—Taipei Documentary Provokes Outrage,” Taipei Times, February 28, 2007, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2007/02/28/2003350348.

[13] “About the February 28 Incident,” 228 Memorial Museum, Taipei Government, May 4, 2015, http://228memorialmuseum.gov.taipei/ct.asp?xItem=1938462&ctNode=41711&mp=11900A.

[14] Cindy Sui, “Taiwan Kuomintang: Revisiting the White Terror Years,” BBC News, March 13, 2016, May 14, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-35723603.

[15] Cindy Sui, “Will the Sunflower Movement Change Taiwan?” BBC News, April 9, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32157210.

[16] Li Thian-hok, “The 228 Incident and Tiananmen Square,” Taipei Times, February 28, 2001, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2001/02/28/0000075544.

[17] “Trial of Lawyer Accused of Subversion Starts in China,” Taipei Times, May 9, 2017, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/world/archives/2017/05/09/2003670246; Stephen Gregory, “Human Rights Lawyers Shine in China, but need the World to Notice,” The Epoch Times, May 22, 2017, http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/2251896-human-rights-lawyers-shine-in-china-but-need-the-world-to-notice/.

[18] Xiaokun Song, Between Civic and Ethnic: The Transformation of Taiwanese Nationalist Ideologies (1895-2000) (Brussels: VUB Press, 2009), 128.

[19] Dr. Lung-chih Chang (research fellow, Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica), in discussion with the author, September 30, 2016.

[20] Wang Kuan-jen and William Hetherington, “Pair Surrenders to Police over Hatta Statue Decapitation,” Taipei Times, April 18, 2017, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2017/04/18/2003668927.

[21] Wang Han-ping and William Hetherington, “Mayor Attends Hatta Statue Unveiling,” Taipei Times, May 8, 2017, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2017/05/08/2003670179.

[22] Nishimoto, “Chiang Kai-shek Statue Beheaded.”

[23] Peipei Qiu, Chinese Comfort Women: Testimonies from Imperial Japan’s Sex Slaves (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 38.

[24] Tomo Hirai, “S.F. Board Unanimously Passes ‘Comfort Women’ Memorial Resolution,” New America Media, October 6, 2015, http://newamericamedia.org/2015/10/sf-board-unanimously-passes-comfort-women-memorial-resolution.php.

[25] Choe Sang-Hun, “Statues Placed in South Korea Honor ‘Comfort Women’ Enslaved for Japan’s Troops,” New York Times, October 28, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/29/world/asia/south-korea-statues-honor-wartime-comfort-women-japan.html.

[26] Howard, True Stories, 32–192.

[27] Howard, True Stories.

[28] Dr. Chu Te-lan and Dr. Lung-chih Chang (research fellows, Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences and Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica), in discussion with the author, October 18, 2016.

[29] Lai et al., Silent Scars, 28.

[30] “7. How Have the Women Lived after the War?,” Fight for Justice, http://fightforjustice.info/?page_id=2772&lang=en.

[31] “Projects by Country or Region-Taiwan,” Asian Women’s Fund, http://www.awf.or.jp/e3/taiwan.html.

[32] Lai et al., Silent Scars, 193.

[33] Lai et al., Silent Scars, 29.

[34] Lai et al., Silent Scars, 102.

[35] Lai et al., Silent Scars.

[36] “Comfort Women Tell Japan to Extend Compensation,” BBC News, December 29, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-35193432.

[37] Lai et al., Silent Scars, 102.

[38] Mark Carnac, “Taiwan Urges Japan to Apologize for ‘Comfort Women’ after South Korean Deal,” Time, December 29, 2015, http://time.com/4164004/taiwan-japan-comfort-women-resolution/.

[39] Lai et al., Silent Scars, 3.

[40] Lai et al., Silent Scars.

[41] “Ratio Identifying as Taiwanese Highest in 20 years: Poll,” The China Post, March 15, 2016, http://www.chinapost.com.tw/taiwan/national/national-news/2016/03/15/460817/ratio-identifying.htm.

[42] Michal Thim and Misato Matsuoka, “The Odd Couple: Japan & Taiwan’s Unlikely Friendship,” The Diplomat, May 15, 2014, http://thediplomat.com/2014/05/the-odd-couple-japan-taiwans-unlikely-friendship/.

[43] Thim and Matsuoka, “The Odd Couple: Japan & Taiwan’s Unlikely Friendship.”

[44] Thim and Matsuoka, “The Odd Couple: Japan & Taiwan’s Unlikely Friendship.”

[45] Ms. Shu-hua Kang (executive director, Taiwan Women’s Rescue Foundation), in discussion with the author, October 24, 2016.

[46] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Announcement by Foreign Ministers.”

[47] “Taiwan President Says,” Reuters.

[48] “About TWRF,” Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation, https://www.twrf.org.tw/eng/p1-about.php.

[49] “[Press Release] Opening Ceremony—Royal Family Peace and Women’s Human Rights Museum,” Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation, December 12, 2016, http://www.twrf.org.tw/amamuseum/news_d9.php.

[50] Keith Menconi, “Lives of Resilience: Reimagining Taiwan’s Comfort Women,” The News Lens, April 21, 2017, https://international.thenewslens.com/article/66537.

[51] Menconi, “Lives of Resilience: Reimagining Taiwan’s Comfort Women.”

[52] Menconi, “Lives of Resilience: Reimagining Taiwan’s Comfort Women.”

[53] Menconi, “Lives of Resilience: Reimagining Taiwan’s Comfort Women.”

[54] To see how the TWRF depicts the lives of the comfort women, see their website at http://www.twrf.org.tw/amamuseum/index.php and a video published by the TWRF at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2nijJEEm7SU.

[55] Menconi, “Lives of Resilience.”

[56] Menconi, “Lives of Resilience.”

[57] Menconi, “Lives of Resilience.”

[58] Menconi, “Lives of Resilience.”

[59] John Power, “[Voice] Is Domestic Violence Taken Seriously in Korea?” The Korea Herald, May 5, 2012, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20120507001291.

[60] Rob Gilhooly, “Learning to Stand up to Domestic Violence in Japan,” Japan Times, March 4, 2017, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/03/04/national/social-issues/learning-stand-domestic-violence-japan/#.WPzav_k1-Uk.

[61] Dan Lamothe, “”The U.S. Military’s Long, Uncomfortable History with Prostitution Gets New Attention,” Washington Post, October 31, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/checkpoint/wp/2014/10/31/the-u-s-militarys-long-uncomfortable-history-with-prostitution-gets-new-attention/?utm_term=.f1fda4b218d1.

[62] Sandy Cameron and Edward Newman, “Trafficking of Filipino Women to Japan: Examining the Experiences and Perspectives of Victims and Experts” (executive summary, prepared for Global Programme against Trafficking in Persons, United Nations University, 2004), 3, http://www.unodc.org/pdf/crime/human_trafficking/Exec_summary_UNU.pdf.

[63] Yabuki Susumu and Mark Selden, “The Origins of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Dispute between China, Taiwan and Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal 12, no. 2 (January 2014): 1–25, http://apjjf.org/2014/12/2/Yabuki-Susumu/4061/article.html.

[64] Shinzo Abe, “‘Towards an Alliance of Hope’—Address to a Joint Meeting of the U.S. Congress” (speech, Washington D.C., United States, April 29, 2015), available at http://japan.kantei.go.jp/97_abe/statement/201504/uscongress.html.

[65] Thim and Masuoka, “The Odd Couple.”

[66] Soh, The Comfort Women, 22–23.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Justice for World War II Comfort Women in Taiwan’s Partisan Human Rights Calculus?

- Statue Politics vs. East Asian Security: The Growing Role of China

- The Comfort Women Controversy in the American Public Square

- Opinion – Beijing’s Weaponisation of Diplomacy Against Taiwan

- Opinion – Taiwan’s Almighty Squeeze

- Opinion – Why Tsai Ing-wen’s Victory is a Blessing for the Taiwan Strait