This is an excerpt from Park Statue Politics: World War II Comfort Women Memorials in the United States. Get your free copy here.

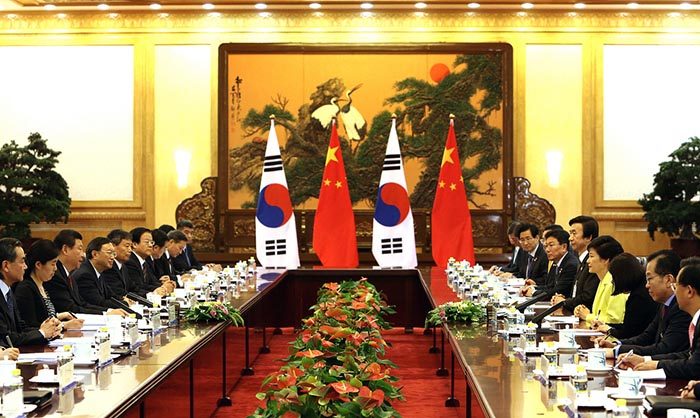

While small towns in the United States are being pulled into the comfort women feud between Korea and Japan, China has made it manifestly clear that it intends to become the new sheriff in the Asia-Pacific region, edging out the United States. It is confronting American sea and air power in the South China Sea and through its new Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in Northeast Asia. While the United States should not seek to thwart China’s legitimate development, neither should it passively stand by and allow disunity among its allies to create a leadership vacuum that an increasingly militaristic and Marxist-inspired China could fill. This would not serve the interests of those who wish China to progress through embracing the rule of law, opting to resolve problems through negotiation and compromise rather than through brinkmanship. Further breakdowns in Korea-Japan relations and perhaps even in U.S.-Japan relations due to inflammatory rhetoric on memorials in small American municipalities and in Congressional resolutions, based exclusively on a Korean account of events that inspires anti-Japanese sentiments, are a cause for concern. In addition to geographic proximity to China and a bilateral volume of trade that exceeds Korea’s cumulative trade with Japan and the United States, Korea and China share a deep-seated hostility towards Japan, stemming largely from unresolved WWII issues.[1] Relations between the Republic of Korea and China have deepened since the 1980s, leading some to foresee an eventual alliance between the two countries.[2]

In San Francisco’s Chinatown, a WWII Pacific War Memorial Hall opened on August 15, 2015, commemorating the 70th anniversary of the “Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression.”[3] Michael Honda, the unflagging U.S. Congressional proponent of a more assertive Japanese apology, was named “Honorary Curator” of the museum.[4] The China Daily quotes Florence Fang, a key figure in the creation of the museum:

The Jewish people and community have established 167 monuments and museums worldwide to memorize the holocaust against Jews. We didn’t even have one to commemorate the contribution and sacrifice of the Chinese people, even though the death toll of Chinese in WWII was 36 million.[5]

The organization spearheading the museum is the Global Alliance for Preserving the History of WWII in Asia. The opening line of its mission statement echoes the Chinese Communist Party in denouncing Japan and asserting that “a full accounting for the Asia-Pacific War is imperative when ruling elements of the Japanese government foster collective amnesia and ultra-nationalistic citizens engage in denial, justification and whitewashing of Japanese war crimes committed in the first half of the 20th century.” [6]

Unlike China, Japan and Korea have fully embraced democracy and the rule of law, with its concomitant attributes of accountability, transparency and accessible, and impartial dispute resolution.[7] U.S.-Korea-Japan cooperation is critically important, especially as China’s “peaceful rise” exhibits a still tenuous commitment to the rule of law and to the peaceful settlement of regional disputes. The world was reminded of this a few years back when a People’s Daily editorial warned that if Hong Kong’s “Occupy Central” disruptions continued, “consequences will be unimaginable,”[8] which could be interpreted as either a warning of socioeconomic collapse or of a potential Tiananmen-style military crackdown. Fortunately both were avoided, hopefully affirming that all sides have learned from the tragedy of a quarter century past. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether sufficient guarantees are in place to assure that the politics of modern China be guided by the rule of law rather than by Mao’s “barrel of a gun.”[9] As we have already stated, Beijing has recently detained not only human rights activists but also the attorneys who dare to defend them .[10] [11] China’s attitude towards civil and human rights will be influenced by the U.S.-Japan-Korea working relationship and the ability of these three countries to convince China to opt for rule of law rather than the dictates of the Chinese Communist Party in addressing problems at home as well as with its neighbors.

Beijing and the Comfort Woman Issue: Pretender, Friend or Foe?

Until now, comfort women memorials have been placed in smaller cities with populations of less than 150,000. In September 2017, San Francisco became the first major U.S. city to install a comfort women memorial.[12] Supporters forged ahead with plans to install a comfort women memorial in an extension to St. Mary’s Square in Chinatown. Although they obtained the approval of political decision-makers, their plans conflicted with the prior agreement of the developer of the site to delegate the selection of artwork there to the nonprofit Chinese Cultural Center with community input. Out of 100 artists worldwide, the piece selected by the community-based group was by Chinese-American artist Sarah Sze. The developer and Sze began working on artwork for the site, but when Sze learned that the comfort women activists had obtained political approval for their statue in the small space, she withdrew her project. The activists later pleaded that they “did not barge in,” and argued curiously that Sze was only a Chinese-American artist but that the comfort women memorial addressed issues related to “Asian-American women in general.” The artist director of the Chinese Cultural Center lamented that “politics trumped the community process.” [13]

Beijing: Vocal on Japan and Mum on Mao

In October 2016, with the help of monies donated from South Korea, a monument which includes both a Korean comfort woman and a Chinese comfort woman was dedicated in Shanghai Normal University.[14] It attracted significant publicity including an exchange of opprobrium between the foreign ministries of Japan and the People’s Republic of China. When Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary and official spokesperson Yoshihide Suga characterized the establishment of the memorial as “extremely regrettable,” China’s Foreign Ministry retorted, calling for a similar memorial in Tokyo to “help Japan unload the burden of history and win the understanding of Asian neighbors.”[15]

However, 2016 did not only mark the creation of the first comfort women memorial in China; it marked the 50th anniversary of the start of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. While the comfort women statues were deemed of sufficient importance to warrant a defense by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, [16] China maintained a guarded silence on the Cultural Revolution throughout 2016. Interestingly, 2016 marked both the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the Cultural Revolution and 40th anniversary of it being halted with the arrest of the Gang of Four shortly after Mao’s death in September 1976. Yet there was no monument dedicated to the victims of the Cultural Revolution, which turned children on parents and claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and resulted in the persecution of “100 million people.” Yet in 2016 there was no ceremony to mourn those victims. There was no state expression of regret for Mao who had rained death and a decade-long nightmare of terror upon his fellow countrymen.[17] Certainly in the decade following Mao’s death in September 1976 there were significant efforts by the Chinese government to rectify the wrongdoings of the Cultural Revolution that all ended with the Tiananmen Square crackdown, which claimed another thousand lives.

One questions the sincerity and extent of China’s concern for human rights. While China memorializes the several hundred thousand comfort women, there exists no monument to the victims of the Cultural Revolution. There is also no monument in China to the tens of millions of victims of Mao’s Great Leap Forward. In a 2010 New York Times editorial, Frank Dikötter, a Dutch sinologist who has studied Mao’s rule of China, reported on his review of hundreds of official documents surrounding Mao’s Great Leap Forward, which took place from 1958 to 1962. The Great Leap Forward was intended to launch China as a model for agricultural and industrial development but proved to be a colossal failure. Dikötter concluded, based on his document review, that the number of deaths during the Great Leap Forward has been downplayed by the Chinese government. He cites the example of his findings in Sichuan Province where one official submitted an uncontested report to the local communist leader Li Jingquan that, in Sichuan alone, 10.6 million people had perished between 1958 and 1961. Dikötter then makes the observation that “in all, the records I studied suggest that the Great Leap Forward was responsible for at least 45 million deaths.” [18]

He stresses that his examination of party records confirms that the Great Leap Forward was not the product of clumsy errors in the government of Chairman Mao, as has been suggested, and that coercion and terror were at the very core of its implementation. Dikötter cites unimaginable acts of cruelty such as the dismembering of people and or being buried alive or drowned as punishment for “crimes” such as “digging up a potato” or taking a handful of grain. And Dikötter maintains that Mao was aware of these tragedies:

Mao was sent many reports about what was happening in the countryside, some of them scribbled in longhand. He knew about the horror, but pushed for even greater extractions of food. At a secret meeting in Shanghai on March 25, 1959, he ordered the party to procure up to one-third of all the available grain – much more than ever before. The minutes of the meeting reveal a chairman insensitive to human loss: “when there is not enough to eat people starve to death. It is better to let half of the people die so that the other half can eat their fill.”[19]

The Black Book of Communism succinctly describes how the deification of Mao and the party defied any pretense of a system of justice: “In China, people were not arrested because they were guilty; they were guilty because they had been arrested.”[20] Yet none of this merits a memorial in China. Does the comfort women memorial honor the women or does it simply feed on China’s competition with Japan in the Pacific?

China’s Modern-Day Comfort Women System Using North Korean Women and Girls

While Korean and Korean-American CSOs collaborate with Beijing-related organizations in the United States in erecting statues to honor the comfort women, they remain mysteriously silent about a phenomenon occurring today in China with young women from North Korea. Tens of thousands of young Korean women have fled the North by crossing the Yalu River into China. They do so with the help of Chinese “coyotes” who bring them to the Chinese mainland for high fees. The fees can be immediately paid by cash or can be paid off once the escapee arrives in China. Frequently, these young women find themselves channeled into prostitution upon arrival in China. Those sent to brothels are deceived in the same way that the “comfort women” were some 80 years ago. Like the comfort women of that period, they are promised work as barmaids or as servers to pay those who smuggled them into China, only to discover that a life of forced prostitution awaits them. Hyeon-seo Lee, a North Korean refugee who escaped to China in the late 1990s, was forced into a marriage and, when the marriage failed, was sold to a brothel which she was fortunate to escape. Her book, The Girl with Seven Names (2015), relates the twisted course she endured to reach Seoul, where she now speaks out against the repression in North Korea and the trafficking of North Korean women in China. Ms. Lee has established an NGO called North Star NK designed to help those trafficked into the sex trade in China to escape. She describes the fate of the “humiliated and broken” women forced into the Chinese underworld:

All but the lucky few will live the rest of their lives in utter misery. They will be repeatedly raped day in and day out by an endless supply of customers who enrich their captors at their expense. [21]

The trafficking of North Korean women has grown since the North Korean famine of the 1990s. One victim, Park Ji-hyun, explains that “human trafficking of North Koreans to China, especially women who will be dispatched to brothels, has become big business.”[22] Park was sold to a Chinese man, lived as his spouse for six years, and gave birth to one child. She then escaped only to be captured and was detained in a camp for North Korean women who had been trafficked and captured in China. The women were forced each day in the first week of detention to strip before male prison guards who inspected their vaginal and rectal cavities for money. They were finally deported back to North Korea where Park was held in a concentration camp for six months. Once released, she again returned to China to find her son. Ms. Park describes it this way:

People just like me – women fleeing a brutal dictatorship, only to be trafficked to a cruel one – are leading lives of perpetual victimization, utterly powerless. Unless the world pays attention, they will remain without protection – and without hope.[23]

One would hope that organizations such as the KAFC and the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan would use their influence to speak out forcefully on behalf of these women who face no choice but life-threatening repression in North Korea or the dangers of forced marriages or sexual slavery upon fleeing to China. One would hope that they would lobby China to allow these women to travel to Seoul rather than to repatriate them to the North as is the current practice.

Korean-American CSOs and Pro-Beijing Organizations: The New Partnership

In 2015, Chinese-American CSOs played the pivotal role in gaining approval of a comfort women memorial in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Two retired Chinese-American judges, Julie Tang and Lillian Sing of the “Rape of Nanking” Redress Coalition[24] have also assumed leadership roles in the “Comfort Women” Justice Coalition,[25] a second anti-Japan initiative which focuses on redress from Japan for the comfort women. The campaigns against Japan for its crimes in Nanjing (Nanking) and for the creation of the comfort station system are understandable; however, the absence of a Great Leap Forward Redress Coalition, a Cultural Revolution Redress Coalition, or a Tiananmen Square Truth Commission points to perilous one-sidedness in this campaign for human rights where Japan is punished and Maoist acts of repression and mass murder are ignored.

Korean-American CSOs that work with pro-Beijing organizations to build more anti-Japan monuments should understand that young North Korean women arrive in China every week to escape the oppression and madness of Pyongyang. While these young women expect to work as servers and restaurant workers, some will be sold as brides upon their arrival to unmarried, often older Chinese men who could not find a spouse. Others will go to the “restaurant or café” where they expect to be servers, only to find themselves in brothels instead where they work as “comfort women.” There are 20,000 to 30,000 North Korean women in China who currently face this tragic fate.[26]

Comfort Women versus China’s Female Victims of Japan’s Imperial Army

Many women in mainland China suffered abduction, rape, and murder at the hands of the Japanese military prior to and during WWII. In October 2015 a monument, which included statues of a Chinese comfort woman and a Korean comfort woman seated beside each other, was erected in Seoul, ostensibly to recall the shared fate of the two countries.[27] In October 2016 a similar monument was dedicated in China.[28] In her study of what she refers to as Chinese “comfort women,” Prof. Peipei Qiu, a literature professor at Vassar College, writes of the tragic circumstances that thousands of Chinese women suffered under Japan’s military. [29]

Japan’s official, government-sanctioned comfort women were channeled through the Ministry of War. They consisted of Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese women, all subjects of Japan, and were conscripted to curb the rape and mistreatment of Asian females in newly conquered territories. These three populations were considered trustworthy because they were subjects of the emperor and thought to be fulfilling a necessary, honorable task through their role as comfort women.[30]

Unlike Taiwanese and Koreans women, Chinese women were not subjects of Japan. They did not warrant trust or an assumption of patriotism toward Japan, especially given China’s massive resistance to Japan’s occupation of the mainland. The Chinese women forced into sexual service by local Japanese military units were viewed instead as “spoils of war,” similar to the Bosnian Muslim women raped and murdered by the Serbs in the 1990s and the Nigerian girls who were kidnapped, raped, and murdered in more recent times by the terror group Boko Haram.

Beijing’s Gains from the Proliferation of Comfort Women Memorials in the United States

New efforts to advance the comfort women narrative in the United States increasingly originate from Chinese-American CSOs. The Chinese denounce Japan’s creation of a system that had no place for Chinese women because they were viewed as a security threat. China’s anti-Japanese CSOs’ goals in jumping on the official comfort women bandwagon are arguably strategic. By supporting and partnering with Korean CSOs and promoting their anti-Japan position, they help to support the growing divide in inter-state relations between Japan and Korea, which serves to undermine the Korea-U.S.-Japan strategic alliance.

Notes

[1] Soh, The Comfort Women, 22–23.

[2] Jin Kai, “Why a China-South Korea Alliance Won’t Happen,” The Diplomat, August 20, 2014, http://thediplomat.com/2014/08/why-a-china-south-korea-alliance-wont-happen/.

[3] Chang Jun, “Chinese WWII Museum Names Mike Honda Honorary Curator,” China Daily, March 2, 2015, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2015-03/02/content_19755364.htm.

[4] Jun, “Chinese WWII Museum Names Mike Honda Honorary Curator.”

[5] Jun, “Chinese WWII Museum Names Mike Honda Honorary Curator.”

[6] “Our Mission,” Global Alliance, http://www.global-alliance.net/mission.html. See also Zachary Keck, “China’s Communist Party and Japan: A Forgotten History,” The National Interest, May 27, 2014, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/chinas-communist-party-japan-forgotten-history-10533?page=2.

[7] See, e.g., World Justice Project, https://worldjusticeproject.org/about-us/overview/what-rule-law.

[8] See “Cherish Positive Growth: Defend Hong Kong’s Prosperity and Stability,” People’s Daily Editorial, October 1, 2014, as translated by Nikhil Sonnad, “Here is the Full Text of the Chinese Communist Party’s Message to Hong Kong,” Quartz, October 01, 2014, http://qz.com/274425/here-is-the-full-text-of-the-chinese-communist-partys-message-to-hong-kong/.

[9] Mao Tse Tung, “Quotations from Mao Tse Tung,” trans. David Quentin and Brian Baggins, Marxists Internet Archive, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/works/red-book/ch05.htm.

[10] “Trial of Lawyer,” Taipei Times.

[11] Gregory, “Human Rights Lawyers Shine in China,” The Epoch Times.

[12] “San Francisco Unveils ‘Comfort Women’ Memorial,” Japan Times, September 23, 2017, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/09/23/national/politics-diplomacy/san-francisco-unveils-comfort-women-memorial/#.Wc66DVvWyUl.

[13] Joshua Sabatini, “‘Comfort Women’ Memorial Costs SF Major Art Project,” San Francisco Examiner, December 28, 2016, http://www.sfexaminer.com/comfort-women-memorial-costs-sf-major-art-project/.

[14] “‘Comfort Women’ Statues Erected in China,” Yonhap News Agency, October 22, 2016, http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/news/2016/10/22/34/0200000000AEN20161022001851315F.html.

[15] “China Prods Japan to Erect ‘Comfort Women’ Statue in Tokyo,” ABS-CBN News, October 25, 2016, http://news.abs-cbn.com/overseas/10/25/16/china-prods-japan-to-erect-comfort-women-statue-in-tokyo

[16] “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Lu Kang’s Regular Press Conference on October 25, 2016,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, October 25, 2016, http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/t1408663.shtml.

[17] Thomas J. Ward, “Remembering the Chinese Spring,” Washington Times, December 27, 2016, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2016/dec/27/remembering-the-chinese-spring/.

[18] Frank Dikotter, “Mao’s Great Leap to Famine,” New York Times, December 15, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/16/opinion/16iht-eddikotter16.html?_r=2.

[19] Dikotter, “Mao’s Great Leap to Famine.”

[20] Jean-Louis Margolin, “China: A Long March into Night”, in The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, ed. Stéphane Courtois, trans. Jonathan Murphy and Mark Kramer (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 507.

[21] “Lottery of Misery: Bleak Choices for N Korean Women,” Taipei Times, November 4, 2016, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/world/archives/2016/11/04/2003658564.

[22] Park Ji-hyun, “Surviving Human Trafficking in the PRC,” Taipei Times, August 23, 2016, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2016/08/23/2003653672.

[23] Ji-hyun, “Surviving Human Trafficking in the PRC.”

[24] “History,” Rape of Nanking Redress Coalition, http://rnrc-us.org/history.htm.

[25] “‘Comfort Women’ Panel Discussion at UC Hastings College,” Comfort Women Justice Coalition, http://remembercomfortwomen.org.

[26] Donald Kirk, “North Korean Women Sold into ‘Slavery’ in China,” Christian Science Monitor, May 11, 2012, https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Asia-Pacific/2012/0511/North-Korean-women-sold-into-slavery-in-China.

[27] “Statues Honoring Korean, Chinese ‘Comfort Women’ Erected in Seoul,” Japan Times, October 29, 2015, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/10/29/national/politics-diplomacy/statues-honoring-korean-chinese-comfort-women-erected-in-seoul/.

[28] “‘Comfort Women’ Statues Erected in China,” Yonhap News Agency, October 22, 2016, http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/news/2016/10/22/34/0200000000AEN20161022001851315F.html.

[29] Peipei Qiu, Su Zhiliang, and Chen Lifei, Chinese Comfort Women: Testimonies from Imperial Japan’s Sex Slaves (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 26–28.

[30] Tanaka, Japan’s Comfort Women, 3.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Unusual Case of Taiwan

- The Comfort Women Controversy in the American Public Square

- The Transnational in China’s Foreign Policy: The Case of Sino-Japanese Relations

- Introducing ‘Park Statue Politics’

- Inconsistencies in the Korean Comfort Women Narrative

- The Competing Narratives of Statue Politics