Early in the morning of April 11th, news that Sudan’s Defence Ministry was going to make an announcement spread throughout the throngs of protesters encamped outside military headquarters in Omdurman. Protesters working to compel the longtime authoritarian leader of Sudan, Omar Bashir, to step down as President, seemed to know intuitively what was to come. Indeed, the Defence Ministry announced that Bashir had stepped down from his nearly thirty-year tenure as the President. The presence of large numbers of Sudan Armed Forces personnel and vehicles, not national intelligence and security service (NISS) or police, was the next sign. The Defence Minister, Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf, announced the army was stepping in to take control after Bashir’s resignation. Further, he indicated a provisional government would be formed in due course. A 3-month state of emergency was declared, with a curfew for all major centers from 10 PM to 4 AM each day for one month. The Minister also explained the army would preside over a shut-down of the city and government for 24 hours while transitional arrangements were resolved. While the Defence Minister was making his announcement, aired on Radio Omdurman, reports were circulating that former President Bashir and a number of senior acolytes were sequestered under a form of house arrest. Similarly, rumors were circulating in the crowds that the major political party leaders were in consultations with top military brass.

By the time of writing, exact details of who was under arrest or simply involved in the process remained unclear. Shortly after the announcement made by the military, the Association of Sudanese Professionals, a leading organizer of the protests, reacted. They called Bashir’s resignation and the moves by the Defence Minister a military coup and that the Association and other protesters would continue their sit-in until a transition to a civilian government was announced. The spokesperson for the groups used the aggressive language that “civilians need now to take power from the military.” New developments unfold rapidly, for example, only 48 hours after taking power the Defence Minister also stepped aside making way for Abdelfattah Burhan Abdelrahman, a former inspector general of the army. It had been anticipated that these events would eventually take place in some form, but not to come so quickly and with so little resistance from Bashir and his main supporters. Initial reflection suggests that it seems the specter of the fate of leaders in Libya and Egypt loomed large for Bashir. Many close to the situation have suggested that the unfolding drama resembles events in Egypt over recent years. Reports indicated that the army, along with securing Bashir and his inner circle, has also begun to seek out and detain those connected to the Muslim Brotherhood in Sudan and those that have strong links to the Islamist groups that helped Bashir come to power in the late 1980s. At the moment there is a major power vacuum, and rumors are running rampant. In such a volatile neighborhood, uncertainty can motivate risk taking and efforts by those so long disenfranchised looking to secure a piece of the emerging political dispensation.

This article considers the key facets of what contributed to the resilience and the eventual fall of Bashir’s regime, combining an examination of domestic and international factors. Despite being one of the more peaceful times in the recent history of Sudan, a major protest movement has brought about political change. Despite prospects of an improving economy, protests were triggered by immediate economic pressures on the middle and professional class. It was a protest movement situated within core political communities of Sudan, not violent insurrection from the periphery that brought Omar Bashir down. Further, the movement for change has been led by a younger generation of professionals, especially physicians and engineers. Bashir’s political economy of power, whereby a militaristic system of patronage has kept him in power, is bankrupt and has apparently run its course. Finally, the article considers how the transition from Bashir to army leaders may not reflect the kind of revolutionary change many are hoping for.

Context: Overreaction and a State of Emergency

For more than three months now, Sudan has seen a sustained protest focusing on the goal of removing President Omar Bashir. The protest was triggered by a radical increase in the prices of basic commodities. The struggling economy has been the focus of much of the attention on the current crisis. The key explanatory factor, however, is not economic problems in general but whom current economic challenges are hurting. A younger professional class living largely around Sudan’s major urban centers in Khartoum and Omdurman are feeling the pressure of rapid inflation and frustration with a clientelist government and broader corruption. They have grown up accustomed to major subsidy and disbursements through a patronage economy. Bashir’s regime used this as a way to maintain support or tacit acceptance of the key political communities in the country.

The mobilization of professionals and youth through new social media and communications, a kind of Arab Spring effect, has been seized upon by a younger disaffected group. Bashir’s internal security apparatus has retaliated against the protests with overreaction, which instead emboldened this group. Although the National Congress Party (NCP)/National Islamic Front (NIF) regime of Bashir have never shied away from violence, controlling the key political communities of Khartoum/Omdurman was before largely done through maneuvering of key individuals in top posts in a patronage system.

At the same time as Sudan’s economy began to open with new engagement across the Middle East and welcome the beginning stages of the USA dropping decades-old sanctions, Bashir’s government removed many of the subsidies that had kept prices low for many consumers. The US did not remove Sudan from the state sponsor of terrorism list, however, which precluded immediate changes in economic activity, importantly including debt relief and capital investments. In reaction to the economic crisis, a campaign began to challenge the government, with many looking for a reprieve from the new price pressure. A group of physicians became the vanguard of the campaign that has revolved around a core group of medical and other professionals based in the major cities of Sudan, especially Khartoum and Omdurman. As the response, security services attempted to prevent the protests by framing them as illegal. Several incidents occurred with police and internal security services injuring protestors. Security services even took to using force at medical clinics and hospitals to find and arrest those who were believed to have key roles in organizing the protests. Both physicians and their patients were targeted. For many, such behavior crossed a line and thus emboldened the protests. Security personnel forcing their way into medical facilities was shown online via social media. This brought the protests significant international attention and drew support of human rights activists. Emboldened protestors continued to organize by using social media and a range of communications tools to organize continued protests.

Unlike previous threats to his regime, this time Bashir has taken the drastic response of a national state of emergency, removing most political officials and reappointing security or military figures across all levels and departments of government. Bashir stepped down from the leadership of the ruling political party, hoping to offer this as a concession. However, his decisions changed little, for many emboldening their commitment as the move was seen by many as a shallow ploy. Arrests of political organizers from major political parties and political families, as well as the arrest and/or threatening members of the major professional associations involved in the protests, have failed to bring the challenge and protests to an end. The protests have expanded further into society, with a body of evidence emerging on social media of the state’s perpetration of violence and rights abuses not only on the initial core professional groups of the protest but more widely in society.

The violent and oppressive reaction by the state security apparatus has apparently spurred the protesters. It is likely that the movement might have petered out in the short term, as so many protests before, had there not been targeting of medical sites and professionals by the security services, video of which circulated and became a call to action. Further to this, many believe that, had the targeting of medical facilities and professionals not taken place in front of the eyes of the world via social media, this protest like so many before would have been short-lived.

Some have evoked the Arab Spring as an explanation of the current crisis and why it may be different from the myriad protests and threats to Bashir and his regime since taking power through a coup in 1989. The dynamics, however, also include major changes in regional and international politics. Combined with similar forces to those that saw protest movements spread across the region during the Arab Spring, these changes have produced more significant challenges.

Bashir the Survivor

Bashir has proven to be a survivor in the face of myriad crises over the years, from international isolation to regionally backed insurgencies, by leveraging domestic political brinkmanship and international maneuver. Wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC), along with a number of his closest acolytes, Bashir’s regime has survived the pressure of the international community and the internal insurrection in Darfur and the East, most spectacularly repulsing the strike directly on Khartoum and the heart of the Sudanese security apparatus in Omdurman by the Darfuri insurgent Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) in 2008.

A subtly negotiated arrangement with Chadian leader Idress Deby in 2008 and reiterated in 2010 has helped secure the Darfur front. Accepting a compromise agreement with southern rebels of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) in 2005 ended the 22 years long civil war, securing Bashir’s regime against the expanding military threat posed by the potential alignment of southern, Darfuri and eastern rebels under the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). Subsequently, Bashir survived the secession of South Sudan and the loss of full control over the oil wealth that has been the lifeblood of his clientelist patronage-based power. For a military strongman, a loss of this kind might have proved ruinous but he proved effective at evoking enough of a religious agenda to secure a cadre of domestic supporters, along with effective management of international relationships.

Sudan and Bashir have been connected with most of the major international events and changes since 2000 and, entering the post-911 era, the current challenges to his regime have all become more poignant and significant. Surviving the end of the Cold War, the Bashir regime managed to rebuff the international drive for humanitarian intervention in the name of “responsibility to protect” in response to genocide in Darfur and avoid (even benefit in some ways) from the global war on terror and the campaign against Al Qaeda. In navigating Middle-East politics and the deep confrontations within the Persian Gulf region, Bashir’s regime simultaneously maintained relations with both Saudi Arabia and Iran despite the fundamental conflict between the two powers. Bashir has even recast himself a peacemaker, recently brokering a revitalized South Sudanese peace agreement which had failed to effectively end that country’s civil war (2013-2018) until his stepping-in in summer 2018.

Counterintuitive Factors

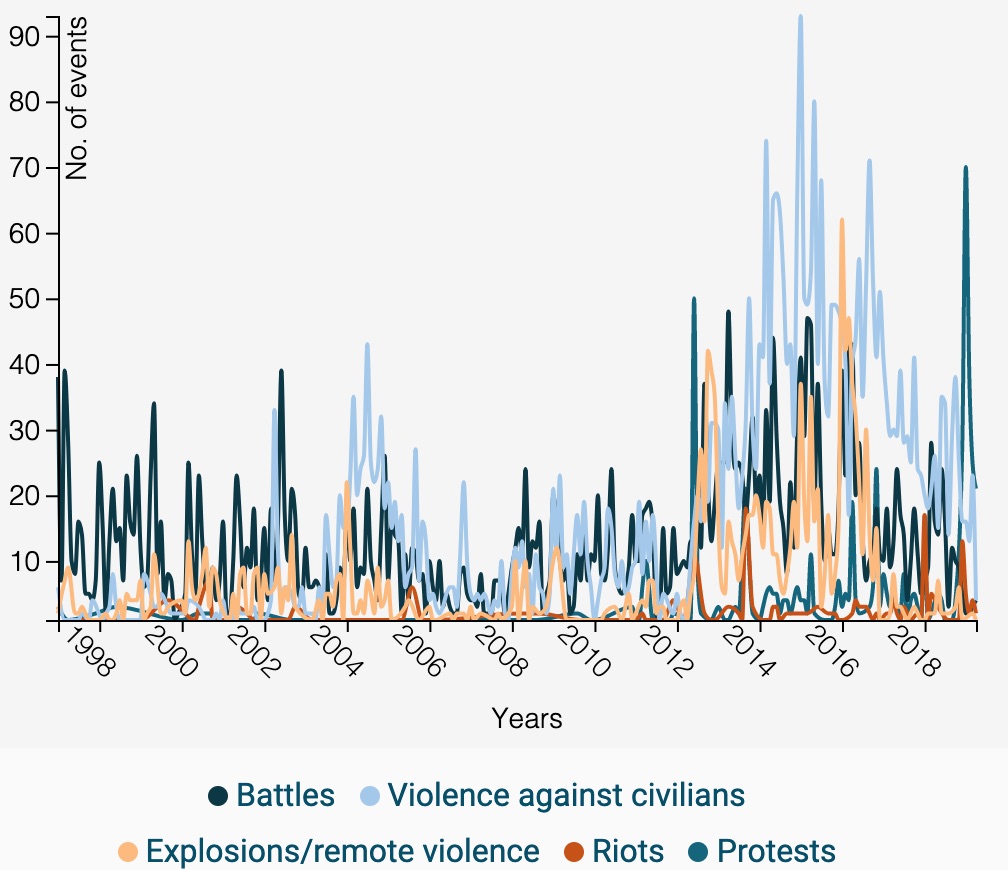

Despite the state of emergency, the current protests have come at one of the least violent points in recent Sudanese history. According to the ACLED database which monitors conflicts, Sudan has seen a significant reduction in incidents of conflict and fatalities in recent years and months. Political developments have also brought the clear likelihood of US sanctions on the regime being lifted, at least in part. Access to parts for industry, capital investments and the ability to sell into global markets without the restrictions of the long-standing sanctions regime appeared set to provide the Sudanese economy with a major boost. However, at the same time as promises were being made of an economic revival, prices rose, inflation set in, and the economy did not grow in a way able to respond to these pressures.

Source: ACLED, March 2019

The stabilization of Sudan’s two main conflicts was due in large part to agreements between Bashir himself and South Sudanese President Salva Kiir as well as a meeting of the minds with Chadian leader Idriss Deby, respectively. Not only did Bashir secure the southern and western frontiers, he also maintained benefit and a level of control over the oil wealth which many regime stalwarts feared would be lost to the southerners after South Sudan’s independence.

At the same time, there was a significant rapprochement between regional state, with all those involved in the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) effectively agreeing to no longer allow oppositions and insurgents of neighboring states sanctuary. An important indicator of this regional thaw was the reconciliation between Eritrean and Ethiopian leadership, which would further spur a dynamic in the Horn of Africa. A major component of the reconciliation has been recognizing the sovereignty of neighbors, working through international bodies and most importantly a move away from tit-for-tat support of neighboring insurgents. Although the improvement of relationship is at an early stage, there is arguably an opening regional economic and political space.

Conventional wisdom would suggest that reduced threat from foreign-backed insurgencies and reduced cross-border insecurity should have helped secure Bashir’s regime. A contradictory dynamic, however, seems to have occurred, whereby Bashir was less able to coalesce domestic groups by using an omnipresent threat from conflicts to compel at least tacit acceptance of his military rule. In the past, conflicts along the borders and in the periphery of Sudan itself allowed Bashir to deflect challenges from opposition groups in Khartoum as he was able to paint the country as facing outside threats. Further, this period of reduced risks of war from outside threats appears to have energized a cross-section of Sudanese society, the young educated/professional class, to challenge Bashir’s long grip on power. This period of relative peace has revealed Bashir’s regime as relying on increasingly corrupt patronage, which many young professionals see as unsustainable.

The economic situation that has in no small part precipitated the protest movement echoes that situation documented preceding the Syrian uprising and crisis in 2011. Dropping of subsidies, inflation connection to some market liberalization and increased internationalization of the economy combined to create conditions where the peasantry was facing poverty, and middle and professional classes faced economic deprivation due to the beginnings of a corrupt version of neo-liberalism[1]. Despite what might have been an equation for economic success in the long run, in the short term, these factors produced poverty and economic distress amongst those formerly experiencing relatively stable standards of living.

Considering the level of violence Bashir’s regime has perpetrated on its own populations such as in the east, south, and Darfur, it may seem remarkable that the current challenge represents a major challenge to the regime given the comparably lower level violence seen since the protests began in earnest in later 2018. The difference is the proximity to the core communities of the leadership of Sudanese political life, which has been the key to national power since independence from the British in 1956.

A Collapsing System of Patronage and Control

In the environment of increased international connection, the current Sudanese protest movement has resulted in a different kind of threat to Bashir’s control. Since Bashir’s military coup in 1989, and going back to Sudanese independence in 1956, Sudanese political life has revolved around core sectarian affiliations for those in the Khartoum/Omdurman powerbase[2]. Since independence, leaders from Khartoum have practiced divide and rule. Bashir, Sadiq Al Mahdi and Nimairi before have all employed some form of patronage mixed with a process of divide and rule amongst political communities, whether tribes or other social groupings residing in the periphery of the main political communities.

The main religious/cultural sects in the center of Sudan have been the primary political powerbase of leaders. Connected to the Shayqiyya tribe of northern Sudan, the Khatmiyya Sufi Order (the Mirghaniyya) is one of the main political communities central to most Sudanese leaders power. The Mahdiyya, or Ansar, an indigenous Sudanese religious and political movement, is the other major competing sectarian affiliation. Bashir’s militarism to some extent created a third grouping, but in many ways co-opted key elements of both orders, allowing the two to continue to exist, with Bashir’s militarists playing the groups off of each other to remain in power. Bashir, himself from the Shayqiyya, came to power through the military and intelligence apparatus, fusing more extreme sections of both main orders with those from the security apparatus frustrated with the perceived weakness of many established political and community leaders when facing increasing threats from rebellions in the south, Darfur, and the east. With major political capital, and associated shifts in resources to serve patronage structures, Bashir thus came to power in a largely bloodless coup, as the leadership of the political parties traditionally connected to the Ansar and Mirghaniyya orders had been severely weakened.

Bashir built a third major political group from the traditional sectarian affiliations, combining the militarists and more religiously zealot embodied by combining political parties National Islamic Front (NIF) and National Congress Party (NCP). A key feature of this political organization was a patronage system which has exacerbated the centralized and corrupt nature of authority and wealth that was already extant in Sudan born of the colonial rule. Bashir also developed a bifurcated security apparatus, with the internal security/intelligence service and military competing with each other. On top of this structure, Bashir’s patronage system also relies on rotating individuals in positions of power and authority, keeping people on the back-foot so to speak, thus maintaining uncertainty and the perpetual risk of losing one’s position and access to capital, essential for leaders to feed their respective branches of the patronage network.

Along with providing special privilege to the elites of those he relied on for power, many mid-level community leaders in the main sects were also placated or sufficiently intimidated. Subsidies, large numbers of bureaucratic posts, and even places in the universities were tactically used to manage the core powerbase of the main political communities outlined above. With economic challenges outstripping Bashir’s ability to secure sufficient outside inputs or leverage internal threats, young professionals and emergent leaders of the two main political groupings have begun to challenge the existing system. As time passed, the system also took on increasingly coercive measures to maintain the loyalty of key figures and their respective networks. With major military threats, the system was effective in maintaining omnipresent others which Bashir used to extort the key militarists and religiously zealot communities. The wavering relationship with both Hassan Turabi (the most prominent religious ideology of the NIF) and Salah Gosh (a longtime intelligence/military strongman), featured by promoting them to top offices, only to remove them and reappoint – even imprison from time to time – is illustrative of how Bashir has maintained control.

The worsening economy has been a key feature weakening Bashir’s ability to maintain control. However, it is a particular aspect of the economic situation that explains the recent unrest rather than simply general economic hardship. While Bashir was able to secure some of the oil wealth when South Sudan seceded, the level of capital from oil has dropped significantly[3]. Bashir has tried to fill the gap with gold and other commodities, but it has not been sufficient. Chinese and other backers, although remaining engaged with Bashir, have increasingly demanded debt arrangements and are pressuring for either larger discounts on the price they pay for resources such as oil or gold or increasingly calling in debts. Bashir has thusly spent an inordinate amount of time directly working to renegotiate terms with Chinese, Saudi Arabian and Malaysian backers. As Bashir worked to bring US sanctions to an end, hoping this would provide sufficient boost to the economy, the short term ramifications of having to drop subsidies have had a much greater impact on the day-to-day financial situation of people. With inflation rising, the longer terms economic development that the drop in sanctions could engender is yet to be seen. The lack of an ability to offer new jobs with sufficient compensation, in the face of a rapidly increasing cost of living in Sudan, has been the main features of the economy that contribute to the conditions for the building protest movement we are witnessing in Sudan.

A Generational Shift

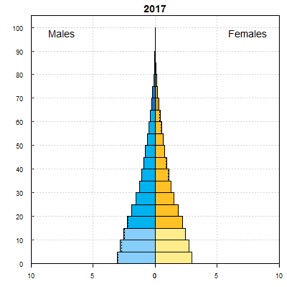

Correlated to the economic situation and a shifting political economy, a generational shift is also occurring in Sudan, which further exacerbates the issues discussed above. A large and growing youth population is a fundamental element of the domestic challenge to Bashir. According to the UN Population Division, of a total population of 43 million, 25 million are under 24 years of age, with tens of millions under 40 years of age. The age gap is also predicted to grow significantly in the coming years.

Source: UN Population Division, April 2019

In the past, going back to the campaign to remove British colonial rule, youth and educated cross-sections of society have been a critical component of the Sudanese political landscape. Leaders have frequently been youthful and often highly educated. Early requirement for things like seats in government reserved for university graduates, “graduate seats”, was an important part of the early post-British movements that brought change. Even Bashir’s own campaign to seize power in 1989 relied on the younger cadres of the military and security services. An indicator of this recognition has been Bashir’s concerted efforts to placate a number of youth organizations. For example, on March 12, he spoke to the Sudanese National Youth Union in Khartoum apparently working to mitigate youth groups’ full and organized entry into the protest movement challenging his rule[4][5].

This generational dynamic has been used to explain political unrest from the Arab Spring in the Middle-East and North Africa, through more recent protests in the Horn of Africa and East Africa. The leadership Bashir has relied upon is growing long in the tooth. The names in high positions of government have remained largely the same for the past twenty years. The attrition of those figures that Bashir could rely upon in leadership dated back to his coup and the early years after taking its toll. Furthermore, in terms of a general movement, the fused NCP/NIF political front Bashir directs has struggled to attract numbers of younger adherents as he was able to do as a much more youthful mid-level military officer.

The two major sects that dominate Sudanese political life, however, have seen a major change with younger figures ascending to prominence, including many that have returned to Sudan after education and time abroad. The longtime leader of the Ansar community, Sadiq Al Mahdi is even believed to be making space for young leaders like his daughter Mariam Sadiq al-Mahdi and a range of more youthful intellectuals from across the professional class, including physicians and engineers.

What comes next?

It is apparent that a new confrontation between the army leadership that take control and the very same protest movement is in the making. Should a sufficient number of political parties not be included in a transitional government and a clear path to new elections of a civilian government be laid out in short order, the Association of Sudanese Professionals will almost certainly continue to protest. Whether the main political parties and associated communities will continue to support protests after Bashir’s ouster is a major question mark. Especially with the prospect of receiving some buy-in to power, there is a high chance they may opt out of a continued protest in lieu of a role in a transitional government.

In the short term what transpires will depend on how the military reacts in the coming days and weeks. Any significant violence will embolden protests and will make it difficult for any transitional government to establish sufficient legitimacy to preclude further mass protest. The first test was going to be if (when) protesters broke the curfew. Apparently recognizing how the curfew was creating the potential for conflict, it was dropped. By shifting to a more conciliatory leader with a much more youthful deputy, the army has shown an ability to manage the situation, without conceding much. If the army remains relatively restrained, we are likely to see a deal between many stakeholders with some protest groups like the professional association and the less mainstream political parties remaining in the streets.

In the medium term, the question is whether the new military leaders able to assuage the underlying economic drivers of the protests. Being central in the construction of Bashir’s militaristic patronage system, the military is unlikely to achieve this goal. Secondly, the unity seen between protesters will be challenged as offers of positions and inclusion in the emerging political process to more orthodox political leaders, particularly from the main political parties connected to the two main political communities/sects. The new leaders have reportedly offered the protest movement the opportunity to nominate someone for the role of interim Prime Minister, which is significant. Such offers of positions look to signal the willingness to accommodate protesters and are meant to assuage accusations against the military for authoritarian take-over. Such offers are also potentially a vehicle to divide and conquer the various civilian political actors.

In the long-term, the question will be whether the army hands over to a civilian authority chosen through free and fair elections. When confronted with a range of regionally popular political parties, the NCP (or an accommodation between the old guard parties from the Ansar and Mirghaniyya political communities) is likely to find some form of coalition to maintain power. Behind the minor shifting of the main leaders of the transitional military government, the top figures of the NCP continue to be looking to hold power. Such maneuvering likely serves to sustain this core elite’s dominance. As a result, the situation is looking more and more like that Bashir was overthrown by his acolytes; in other words, effectively Bashir cut a deal to secure himself. Many of these leaders, like Bashir, are complicit in mass atrocity and failed governance and this is not lost on many Sudanese. These figures may be the only option for Bashir to remain in a relatively comfortable situation. So it was in Bashir’s interests to step down and hand power to those closest to him rather than delay and allow more radical figures to push for power. This kind of accommodation is almost certainly not going to satisfy protesters. In the face of sustained persistence by protestors for a more comprehensive transformation, even revolution, will Sudan’s transitional leaders reign in the army (especially the paramilitary elements) or will they unleash it?

Notes

[1] Yassin-Kassab, R., & Al-Shami, L. (2018). Burning country: Syrians in revolution and war. Pluto Press. P. 33.

[2] Al‐Shahi, A. (1979). Traditional politics and a one‐party system in northern Sudan. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 6(1), 3-12.

[3] Sharfi, M. H. (2014). The dynamics of the loss of oil revenues in the economy of North Sudan. Review of African Political Economy, 41(140), 316-322.

[4] Sudan News Agency, “Al-Bashir Affirms State Support to Students Union Programs” March 4, 2019.

[5] Beladi Radio, Khartoum, “President Al-Bashir Affirms State Concern with Youth Union Programs” March 12, 2019.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Impact of Omar Bashir’s Overthrow on Peace in South Sudan

- Opinion – The Sudanese Conflict and the Abyei Dispute

- Self-Determination as a Process: The United Nations in South Sudan

- Unseen Frontlines: Narratives on Sudanese Women in War

- Africa’s COVID-19 Exceptionalism? Same Problems, Different Locations

- The Internal Displacement of People in South Sudan