This is an excerpt from Regional Security in the Middle East: Sectors, Variables and Issues. Get your free copy here.

Population growth directly affects the sustainability of a society’s resource base under the pressure of its needs and demands (Choucri and North 1995, 232). Put differently, the greater the population, the greater is the aggregate demand for resources. Yet, demographic correlates considerably affect governmental policies and constrain state actions. Since rising density in the international system is driven, among other things, by the increasing population, this, in turn, implies that people’s activities are more likely to impinge on the conditions of other people’s existence, both intentionally and unintentionally, and positively as well as negatively (Buzan 1991, 41). Therefore, the study of the impact of demographic factors is central to any integrated approach to security. There is a clear link between demographic and migration trends in the sense that migration, whether in its domestic or international form, constitutes one of the most important parameters/variables when studying population growth. Consequently, significant migration flows may add to demographic pressures facing states and societies. Therefore, it is not a coincidence that migration is widely viewed by the national publics of the host states as posing threats to their national security, as well as to international stability.

Thus, the security implications (military, political, societal, economic and environmental) stemming from increased migration have the potential to enhance the salience of the security implications, which result from other aspects of population growth. Most importantly, due to their securitisation, migration trends have become a matter of high domestic and international politics. Note, for example, the rise of anti-immigrant political parties and increasing demand for anti-migration policies. Although the separate literatures on migration and security have grown substantially since the early 1990s, few studies directly address the linkage between the two (Kleinschmidt 2006, 9–10; Guild and van Selm 2005, 1–2). As Nazli Choucri suggests, ‘the connection between migration and security is particularly challenging and problematic because migration, security, and the linkage between the two are inherently subjective concepts’ which are dependent on ‘who is defining the terms and who benefits by defining the terms in a given way’ (Choucri 2002, 98).

Initially, approaches to the phenomenon of migration were predominantly economic (Klein 1987; Simon 1989). However, economic approaches and explanations neglect two critical political elements: first, population movements are often encouraged or prevented by governments or political forces for reasons that may have little to do with economic conditions; and second, even when economic conditions create inducements for people to migrate, it is governments that decide whether migrants should be allowed to enter their state territories and their decisions are frequently based on non-economic considerations. Governments wish to control the entry of people and regard their inability to do so as a threat to their sovereignty and security.

However, economics does matter. Even a country willing to accept immigrants when its economy is booming is likely to alter its immigration policy in a recession. But economics alone does not explain the criteria countries employ to decide whether a particular group of migrants is acceptable or is regarded as threatening. In reference to demographic factors, discussion within the broader security perspective focuses on three areas: first, the impact of demographic growth on the security of political, societal, economic and natural environments; second, the population structure and its relevance to the economic performance of states; and third, voluntary or forced migration of large populations within and among states. However, demographic growth should be seen as a challenge rather than a security threat in the sense that depending on other conditions on the ground, it may either add to or detract from the security of the state. This is because the composition and distribution of populations significantly affect how demographic variables relate to other socio-political and economic phenomena (Choucri 1997, 96).

Demography and Demographic Variables

Demography is the study of human populations – their size, composition and distribution across space – and the process through which populations change (Preston et al. 2001; Daugherty et al. 1995). Births, deaths and migration are the ‘big three’ variables of demography, jointly producing population stability or change. In terms of spatial distribution of a country’s population, the study of urbanisation trends is of special importance since major political struggles that have the potential of impacting a state’s political and societal security tend to begin in cities before they spread into the rural areas.

In terms of their relevance to security, one of the most important aspects of demography includes the composition of national societies in terms of race, ethnicity and religion as well as in relation to their foreign-born population. As mentioned earlier in this volume, population composition is of special significance for the development of the state-nation where the management of relations among social groups is imperative for ensuring the socio-political cohesion of the state.

Lastly, of major importance is the study of ‘demographic transition’, meaning transition from high to low levels of fertility and mortality. Structural explanations for the fertility transition have involved the rising cost of raising children because of urbanisation, the growth of incomes and non-agricultural employment, the increased value of education, rising female employment, child labour laws and compulsory education, and declining infant and child mortality. One of the consequences of the decline in fertility has been the aging of the population. Population age structure depends mostly on fertility rates: high-fertility populations are younger and low-fertility populations are older.

Demographic Developments in the Middle East

It has been shown that population growth causes certain political, social, economic, and environmental problems which, in turn, may fuel domestic conflict which can easily spread beyond national boundaries and, therefore, endanger regional security (Choucri 1984). A region interdependent politically as well as economically is certain to share those consequences. Thus, demographic factors are of crucial importance for current and future stability in the Middle East (Crane, Simon and Martini 2011).

Population Growth

Since the mid-1960s, most countries across the Middle East have gone through a ‘demographic transition’ leading to an accelerating population growth (Gillis et al. 1992; Rashad 2000; Bongaarts and Bulatao 2009). As a result, the total population of the Middle East has increased from around 110 million in 1950 to 569 million in 2017 (McKee et al. 2017, 4; UNDESA 2017). However, in recent years, fertility rates began to decline, in part due to the modernisation process, including educational, economic and social progress, and in part due to family planning, urbanisation and shifting patterns of migration (Puschmann and Matthijs 2015; Mirkin 2010; Tsui 2001; Fargues 1989). Nevertheless, due to population momentum, which is generated by the high proportion of women of childbearing age, absolute population numbers are expected to further double to over 1 billion inhabitants by 2100 (McKee et al. 2017, 5–6).

Within this population increase, there have also been transitions in the gender and age-specific ratios, which further enhance the effects of the overall population increase. Exploring Middle Eastern populations by gender reveals that the male population is and will remain marginally higher than the female population (Luy and Gast 2014). Due to regional conflicts, the ratio of male survivors to females above the age of retirement for the region has continued to decrease since 1980. The recent conflict in Syria, however, has seen an eight-year reduction in life expectancy for men relative to a reduction of just over one year for women (Loichinger et al. 2016). This trend of fewer men surviving to older age than women do implies that greater numbers of women are likely to be widowed and thus have proportionally higher levels of dependency among the older age categories than men (UNDESA 2017).

Aging

Age-specific ratios provide an important insight into both current and future trends of demographic transitions in the Middle East (El-Khouri 2016). Whereas today, the region is endowed with a young population, this picture is expected to change dramatically over the coming decades as the fastest-growing age group is the group beyond 64 years of age (McKee et al. 2017, 8). As people in the Middle East age, their social needs and potential economic contributions transition (Loichinger et al. 2016; Saxena 2013). Consequently, social protection systems in the region would face the need to both extend and improve upon services offered to youth of working age, as well as prepare these systems to meet the evolving needs of aging populations (Loichinger et al. 2016).

‘Youth Bulge’

The 2016 Arab Human Development Report concluded that the current Arab youth population is ‘the largest, the most well educated and the most highly urbanised in the history of the Arab region’ (UNDP 2016, 17). Large youth populations, however, present particular challenges. For example, correlations between youth unemployment rates and civil unrest have been drawn, particularly in Middle Eastern countries where the capacity to generate educational and employment opportunities, as well as avenues for political participation are limited (McKee et al. 2017, 5–9; Malik and Bassem 2013).

Education rates improve the potential for inclusion in ‘legitimate’ labour market activity, while at the same time prevent youth from engaging in unlawful activity (Raphael 2001; Grogger 1998). Youth unemployment, youth bulges and education were identified as critical contributing factors leading to the 2011 Arab uprisings (Paasonen and Urdal 2016; Courbage and Pushmann 2015).

(Un)employment

Poorly functioning labour markets in the Middle East and the absence of lawful economic opportunities are likely to make illicit, informal economic activities more attractive. While youth unemployment rates are universally higher than the average unemployment rates of many world regions, the Middle East has significantly higher and widening levels of youth unemployment rates (McKee et al. 2017, 9). Issues of youth unemployment affect countries already afflicted by social conflicts more significantly (Rashad and Khadr 2002). In addition, whereas education is seen to contribute positively to the likelihood of employment, the Middle East is distinguished in that those who have obtained higher levels of education face similar levels of unemployment to less educated people (ILO 2015 and 2017). Thus, providing employment opportunities, as well as quality education, vocational training, health services, and social protection services (i.e. unemployment insurance schemes and income support) to this rapidly expanding labour force is a critical component in determining the broader social implications of population growth across the Middle East (McKee et al. 2017, 10). Yet, as youth population starts to decline across the region, youth employment will become increasingly important in preparation for demographic aging.

Health, Education and Social Services

As Middle Eastern states experience a demographic transition, emergent social issues will also transition. Adapting to shifting demographic dependencies requires governments to introduce more targeted social protection services that would support the more vulnerable elements of society (i.e. unemployed youth, migrant workers, retirees, female citizens, etc.). Concerns will eventually shift from youth unemployment to those pertaining to an aging population and the need to invest in retirement plans (Hussein and Ismail 2016). Moreover, for rapidly aging countries, the prevalence of diseases associated with old age (i.e. diabetes, cancer, heart disease, etc.) are likely to increase dramatically in the near future. Consequently, aging populations are likely to increase the public and private financial burdens of increased social welfare costs and further exacerbate inequality (McKee et al. 2017, 12; Taboutin and Schoumaker 2012). Financing retirement also has implications for national savings levels and funds for investment. Hence, it is expected that investment priorities and the distribution of state subsidies would shift considerably.

Regarding healthcare concerns and costs, one should add nutrition-related concerns that give rise to questions pertaining to food security (Popkin, Adair and Wen Ng 2012). Although malnutrition is now less widespread, it has been argued (McKee et al. 2017, 17) that dietary deficiencies and nutritional disorders in the Middle East are still far too common. Besides augmenting food supplies, a whole range of measures need to be taken, including more local food processing and enrichment, pest control, and general health education.

Despite the progress that has already been made in providing schools and educational services of all kinds, a high proportion of adults, particularly females, remain illiterate. Even among children, rapid population growth sometimes offsets extensive school building programs (McKee et al. 2017, 15). Thus, illiteracy is still common among the economically active population and it is expected to have important implications for the economic development of the region (Hoel 2014).

Urbanisation

Urbanisation continues to gain momentum across the Middle East. Almost 90% of absolute population growth across the region will be generated from urban areas by 2050 (McKee et al. 2017, 18). Thus, the Middle Eastern cities are increasingly congested and filled with young populations often frustrated in their aspirations. Under the pressure of these high population numbers, municipal services break down and the quality of life suffers drastically. This is because people are without adequate water, sanitation, health, education, and other social services. Awareness of the great disparity in wealth and poverty among the urban population contributes to alienation and frustration on a massive scale. Urban centres thus become forcing grounds for criminality and violence (Gurr 1970).

Moreover, the often deplorable living conditions in urban centres contain the seeds of social unrest and political turmoil. Some Middle Eastern states have thus suffered the breakdown of governmental authorities and have become virtually unmanageable. Others have been governed by increasingly repressive regimes leading to a decline in their perceived legitimacy. The Arab Spring has clearly demonstrated that when the resources of a state are severely strained, those at the bottom of the social hierarchy come to realise that those at the top distribute the benefits in ways that favour some groups at the expense of others. These are the circumstances from which social revolutions are born.

Urbanisation places added pressures on the need for expanded social services associated with rapid population growth, because urban development requires more investment in infrastructure than does rural development. At the national level, much investment needs to focus on maintaining the viability of cities, such as providing work, housing, transport, electricity, water and education, as well as maintaining public health and public order. Although this may promote general economic development, the need to support the cities emphasises two important development problems: feeding the urban population and improving the distribution of goods and services across national space.

The necessity for urban planning in the Middle East is clear enough. The planning response, however, has been largely ineffective. Apart from the oil-rich states, like Saudi Arabia, financial problems impeded the implementation of planning policies. It should be recognised, however, that in addition to geographical factors, which offer certain advantages to some states and not others, decongestion and decentralisation are both difficult to achieve in the presence of powerful economic pressures.

Urbanisation also increases the pressures on local agricultural systems because a great number of people are moving to the cities from the countryside. They do so because of the higher income levels in the cities. They also move because population growth in the countryside stretches available food, water, arable land, and other resources, or because they have been displaced from subsistence farming as land is turned to commercial cultivation. Because of the decreasing number of peasants, the need to import food from abroad increases, thereby further straining already limited resources and raising concerns about food sovereignty and food security.

Owing to the already limited availability of arable land and water resources and daunting economic diversification issues, such population growth projections will likely continue to pose a significant challenge to countries in providing employment opportunities and food security. It is especially evident that the three major river basins needed for local and regional food production will see dramatic population growth. This is especially true for the Nile basin and the Euphrates basin (Allan 1993; Beaumont 1978). However, the Jordan basin will see even more dramatic changes given its size and natural endowments (Beschorner 1993). Furthermore, while considerable scope for improvements in agricultural and water productivity exist across the region, population growth, the accompanying increases in urbanisation and demand for housing are resulting in urban encroachment.

Urbanisation can also have implications for an aging population. Whereas higher numbers of children in rural settings can offer labour support for family farms, and represent fewer challenges in housing and childcare costs, in urbanised settings population aging increases the burden upon national social protection systems (Yount and Sibai 2009).

The high level and distinct patterns of food consumption among urban populations in conjunction with the relatively declining rural production represents a growing challenge for Middle Eastern governments and for food system in general (Popkin et al. 2012). A growing reliance on imported food supplies to meet the needs of expanding populations will likely further exacerbate trade imbalances and vulnerability to world food price volatility and export restrictions. Such vulnerability is particularly pronounced among countries either with trade deficits, severe land and water limitations or limited means to increase agricultural productivity.

In sum, urbanisation creates three basic development problems. First, it contributes to an unequal distribution of national wealth between the core and the periphery, while the daily contrast in the cities between the wealthy elites and the poor masses dynamitise domestic stability. Second, the state is unable to absorb the massive labour force that concentrates in the cities. Thus, unemployment and poverty increase the level of popular frustration, which may lead to social unrest. Under certain conditions, frustration leads to acts of aggression against foreign workers who are seen as responsible for the unemployment rates. Third, urbanisation demands high levels of investment. Economic problems, however, pose great constraints to government policies because there is a basic dilemma in defining the hierarchy of priorities. Current population growth tends to increase further the urbanisation problem and, consequently, economic and development concerns.

Migration: Types and Perceptions

Generally speaking, a migrant is a person who moves, either to another country (international migrant) or within their own (internal migrant). People who move inside their country’s borders to survive the outbreak of a conflict are called ‘internally displaced people’. This is an important group to include in the analysis of Middle East migrant populations since conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen have displaced millions of people within their countries in recent years.

Many international migrants move for job opportunities, to join family or to study, while others move to another country to escape violence or persecution. These forcibly displaced persons are called ‘refugees’ and ‘asylum seekers’. However, under certain circumstances, the distinction between refugees and non-refugee ‘foreigners’ is blurred in the eyes of the natives of the receiving states. This happens particularly in countries where there are already problems between natives and non-refugee migrants.

There are three distinct types of forced and induced immigrations (Weiner 1992, 98–100). First, governments have forced migration as a means of dealing with political dissidents (Kulischer 1948) and in an effort to reduce or eliminate from within their own borders selected social classes or ethnic groups (Glazer 1985; Zolberg et al. 1989). Second, forced migration has also served as a means for states to achieve certain objectives. Governments, for example, have used migration as a way of extending their political and economic interests, acquiring recognition, putting political pressure on neighbouring countries, destabilising them, preventing them from interfering in their internal affairs, and prodding them to provide aid or credit in return for stopping the flow of immigrants (Glazer 1985). For example, in the late 1960s and during the 1970s Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia encouraged their citizens to move to France as a way to reduce unemployment at home and at the same time receive remittances that became a significant portion of their national economies. Third, governments may force migration as a means of achieving cultural homogeneity or asserting the dominance of one ethnic community over another (Tucker et al. 1990). For example, Turkey has forced the migration of Kurds from the Turkish territory into Iraq as a way to control Kurdish political activity in Turkey.

Contemporary population movements are linked to the rise of nationalism and the emergence of new states whose boundaries have divided linguistic, religious, and tribal communities (Weiner and Stanton-Russell 2001). The result of this division has been that minorities, fearful of their future and often faced with discrimination and violence, have often migrated to neighbouring states to join other communities with whom they share the same ethnicity. Additionally, some developing countries have expelled their ethnic minorities when the latter were economically successful and competed with a middle-class majority. Furthermore, governments facing unemployment within the majority community and conflicts among ethnic groups over language and educational opportunities have often regarded the expulsion of a prosperous minority as a politically popular policy (Weiner 1992, 107).

Because in the political and social realms, security is related to collective identities, it constitutes a social construct (Weiner 1993; Choucri 2002). As such, security obtains different meanings in different societies. An ethnically homogeneous society, for example, may place a higher value on preserving its political and cultural identity than does a heterogeneous society and may therefore regard an influx of migrants as a threat to its security. Yet, providing a haven for those who share one’s values is important in some countries, but not in others. Moreover, even in a given country what is highly valued may not be shared by the entire population. The influx of migrants may be feared by a government but welcomed by the opposition. One ethnic group may welcome migrants, while another is opposed to them. The business community may be more willing than the general public to import migrant workers.

Explanations for the response of migrant-receiving countries can be divided into two categories. The first is the host country’s economic absorptive capacity. It is plausible, for example, that a country with little unemployment, a high demand for labour, and the financial resources to provide the housing and social services required by immigrants, regards migration as beneficial, while a country low on each of these dimensions regards migration as economically and socially destabilising. For example, the Gulf States and Israel have encouraged the influx of economic migrants because they needed additional labour to meet their economic development.

Second, in terms of migration volume, a county faced with a large-scale influx in relation to its population size may feel more threatened than a country experiencing a small influx of migrants. However, this is not necessarily because of economic reasons. According to Myron Weiner (1992, 92–94), the reluctance of states to receive migrants and refugees is only partly a concern over economic effects. The constraints are as likely to be political, resting upon a concern that an influx of people belonging to another ethnic community may generate xenophobic sentiments, conflicts between natives and migrants/refugees, and the growth of anti-migrant, right-wing parties. Indeed, the second and most plausible explanation for the willingness of states to accept or reject migrants is ethnic affinity. A government and its citizens are likely to be receptive to those who share the same language, religion, or race, while it might regard as threatening those with whom such an identity is not shared.

How and why some migrant communities are perceived as threats to the identity of the receiving state is a complicated issue, involving initially how the host community defines itself. Cultures differ with respect to how they define who belongs to or who can be admitted into their community. These norms govern whom one admits, what rights and privileges are given to those permitted to enter, and whether the host culture regards a migrant community as potential citizens. A violation of these norms is often regarded as a threat to basic values and, in that sense, it is perceived as a threat to national security. However, there is always a possibility that host societies may display hostile attitudes toward migrant communities even in the absence of norm violation.

The perceived efforts of migrants to maintain their cultural and ethnic identities are often blamed as a cause of conflict within states. What some see as a development that enriches a society’s diversity and cultural character, others view it as a threat to their own culture and conception of themselves.

In recent years, the increase in international migration and refugee flows has given rise to paranoia and xenophobia. Migrants very often live a tenuous existence, rarely gaining the same rights as non-migrants, while their hosts are usually aloof. Blamed for a range of ills – from unemployment to crime, strained social services to lack of national unity – migrants are aware of just how easily their rights can be swept away (Heisler and Layton-Henry 1993). The plight of refugees is even worse (Robinson 1998).

Causes of Migration in the Middle East

Between 2005 and 2015, the number of migrants living in the Middle East more than doubled, from about 25 million to around 54 million (Connor 2016a). Two are the main reasons for migration during this period: the search for economic opportunities and the existence of regional conflicts.

Middle East Economic Growth and Economic Opportunities

Despite the initial drop in oil prices and the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, the economies of Persian Gulf countries expanded considerably between 2005 and 2015. This economic expansion in countries like Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and Bahrain has encouraged millions of migrants to move to the Middle East in search of economic opportunity. In fact, around 40% of the growth in the Middle East’s migrant population during this period has been due to individuals and families seeking economic opportunities (Connor 2016a). However, the recent slowing of job growth in the Gulf States has resulted in a growing number of unemployed migrant workers leading to a decline in migrant remittances from the Gulf (Kumar 2016). Israel is another destination for migrants in the Middle East in part because of job opportunities there due to the repatriation of Jews.

Regional Conflicts and Migration

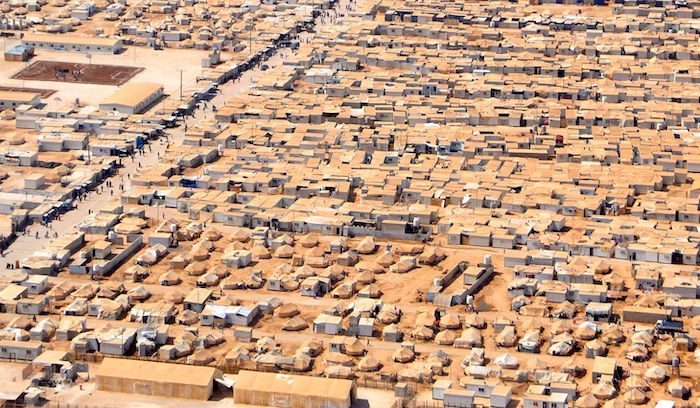

The majority of the migration surge in the Middle East, especially after 2011, was a consequence of armed conflict and the forced displacement of millions of people from their homes, many of whom have left their countries of birth (Heinitz 2013, 18). The rapid rise in the number of people looking for safe havens and new livelihoods has transformed the Middle East into the world region with the fastest growing international migrant and forcibly displaced population. In 2015, Syria (7.1 million) and Iraq (4.7 million) were home to the largest displaced migrant populations in the Middle East. Large numbers of displaced migrants were also living in Jordan (2.9 million), Yemen (2.8 million) and Turkey (2.8 million) (Connor 2016a). According to Philip Connor (2016b), such ‘migration erodes the economies, social fabric, security and administrative capacities of most of the countries in a volatile region with consequences spilling into Europe, especially through illegal, hazardous migratory flows that too often result in the tragic loss of human lives’. Pressures on Middle Eastern countries will intensify as the regional population is expected to double by 2050.

The demographic composition of recent refugees differs from the typical native population in the Middle East. The refugee populations are made up of more children and women compared to the population of the origin countries. More than half of the Syrian refugees, for example, are under the age of 18, compared to about 40% of the pre-war Syrian population (Connor 2016a).

The number of internally displaced persons in the Middle East has grown rapidly over the past decade. In 2005, slightly more than a million people living in the Middle East had been displaced from their homes and were living in their countries of birth. By 2015, the number had climbed to about 13 million (Connor and Krogstad 2016). As of 2015, nearly all internally displaced migrants in the Middle East lived in just three countries: Syria, Iraq and Yemen.

The conflict in Syria had left about two million Syrians internally displaced by the end of 2012. As the insurgency opposed to President Bashar al-Assad’s regime intensified and the caliphate declared by the militant group ISIS continued to expand across Syria, this number of internally displaced persons grew to 6.6 million by the end of 2015 (Connor and Krogstad 2016).

Sectarian violence in Iraq led to a total of 2.6 million internally displaced people within Iraq by the end of 2008. The number of Iraqis displaced within their country then declined, as the intensity of civil strife subsided. However, armed campaigns by ISIS soon drove more people from their homes. The number of internally displaced Iraqis rose from slightly less than a million in 2013 to more than 4.4 million by 2015 (Connor 2016a).

In Yemen, conflict also grew the number of internally displaced people. While this population numbered in the hundreds of thousands through 2014, a subsequent surge in violence increased the number of internally displaced Yemenis to more than 2.5 million by the end of that year (Connor 2016a).

Millions of people, while remaining in the Middle East, have crossed international borders as refugees or asylum seekers. A total of 9.6 million refugees or asylum seekers lived in the Middle East as of the end of 2015, up from 4.2 million in 2005 – a nearly 130% increase. In 2015, 85% of refugees and asylum seekers in the Middle East lived in just four countries: Jordan (nearly 2.9 million), Turkey (about 2.8 million), Lebanon (about 1.5 million) and Iran (about 1 million). The number of refugees living in Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon grew rapidly after the onset of the Syrian conflict. Meanwhile, the number of refugees in Iran has been somewhat stable at roughly 1 million for the entire decade, with most of this refugee population displaced from neighbouring Afghanistan. Iraq (285,000 refugees and asylum seekers in 2015) has seen a rapid rise in persons displaced from neighbouring countries after 2011 as well, mainly Syria. Yemen (277,000 refugees in 2015) and Egypt (251,000 refugees in 2015) have also seen their refugee populations swell, due in large part to conflicts in Somalia, Ethiopia and other countries in sub-Saharan Africa (UNDESA 2015).

The majority of refugees and asylum seekers in the Middle East in 2015 can be traced to three points of origin: Syria (4.6 million), the Palestinian territories (3.2 million) and Afghanistan (1.0 million). As of the end of 2015, nearly all of Syrian refugees in the Middle East lived in just three countries: Turkey (2.5 million), Lebanon (1.1 million), and Jordan (628,000). Outside of the Palestinian territories, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria host Palestinian refugees. Meanwhile, Afghan refugees living in the Middle East are mainly located in Iran (UNDESA 2015).

Demography, Migration and Security

Demographic factors in the Middle East have important implications for all security sectors. What it is important to note is that due to security interdependence, threats operating in one sector may quickly spill over into other sectors. For example, although water resources is an issue that is mainly associated with the environmental sector, access to water may become a military security issue or an economic security issue.

Military Security

In the military sector, the main preoccupation is the survival of the state and one of the main referent objects of security is the physical base of the state (territory and population) (Buzan 1991, 116–117). Therefore, the primary concern of governments is national defence and national leaders make careful calculations about the conflicts they wish to become involved in and how to go about them as they are primarily interested in avoiding the devastating consequences of a military defeat.

In the military sector, demography is usually associated with the number of people available to serve in the armed forces or mobilised for national defence purposes. Therefore, high fertility and low mortality rates, which lead to population increases are preferred to population decline and aging.

Migrants may threaten the military security of states in, at least, five ways. The first is when migrants use the territory of the receiving state for initiating military activities against their home country. For example, it has been claimed that Syrian rebels use the territory of neighbouring states to regroup and prepare their attacks against the Assad regime. Second, refugees may convince the receiving state to undertake direct actions against their home country. For example, the Palestinian refugees in Jordan not only revolted against the regime of King Hussein but also attempted to rally Jordanian support against Israel. Jordan, on the other hand, has been very careful not to allow the Palestinians to draw Amman into a war with Israel that may have negative consequences for Jordan. Third, the receiving state may have an interest in challenging the regime of the migrants’ home country and uses them as a means to this end. For example, Syrian refugees may be used as an excuse for Turkey to challenge Assad’s regime. Fourth, migrants may threaten the military security of their home country by providing financial and military assistance to rebel groups. Thus, struggles that could otherwise take place within the home country are internationalised.

However, there is another way in which population growth and migration trends are relevant to military security in the Middle East, namely population increases leading to increased dependence on international rivers.

Specifically, the main water resource in the Middle East has been the rivers, which usually cross more than one country. In the past, water resource development has taken place largely at the local level. With increasing populations, and in particular the rapid growth of large cities, local water sources are often inadequate to supply the new demands (Beaumont 1993). As a result, individual countries have had to resort to the implementation of a number of large water resource projects, such as river dams, which have had an impact on riparian states. Consequently, significant problems have been created between states resulting from the efforts of some countries to control the water flow of rivers. The already old conflicts between Turkey and Iraq as well as between Egypt and Ethiopia are illustrative of this point. In fact, optimum river resource utilisation relies on a large measure of co-operation between riparian states and unilateral action by a riparian state is extremely prejudicial to regional security (Naff and Matson 1985; Starr and Stoll 1988; Yong 1989; Starr 1991).

In the near future, Egypt, Sudan, Syria, and Turkey, which constitute more than 60% of the region’s population will be dependent upon the Nile, Euphrates, and Tigris rivers by 2100, compared with 48% today (McKee et al. 2017, 6). This increased dependence on international rivers will not only have significant implications for the viability of supporting the likely increases in agricultural, industrial, and municipal water demands, but may also impact transboundary governance and lead to water access related conflicts.

Political Security

In the political sector, threats to the state usually result from a political struggle over the state’s ideology, which may lead to governmental actions that would threaten individual citizens or groups (Buzan 1991, 118–119). Resistance to the government and efforts to overthrow it threaten state stability and enhance regime insecurity. As the Arab Spring has shown, the inability of Middle Eastern states to address the needs and concerns of their citizens has led to resistance and demands for political change that have challenged the organising ideologies of regional states. In fact, the 2011 Arab uprisings have challenged autocracy as a state ideology and have, by the same token, brought about the possibility of democracy as an alternative state ideology. Therefore, population increases may further reduce the ability of Middle Eastern governments to provide social services and economic opportunities to their citizens, which, in turn, may increase further the insecurity of political regimes. Efforts of those regimes to secure their access to power would generate insecurity to the citizens of the state. In this way, a spiral mode of political insecurity comes into existence.

Political threats undermine the organisational stability of the state by threatening its national identity and organising ideology, as well as the institutions that express it (Buzan 1991, 119). In this sense, when migrants and receiving states share similar ideas, host countries may pose political threats to the ideology of the migrants’ home country. On the other hand, when migrants are holders of an ideology different from that of the receiving state, then they may be perceived as a threat to the ideology of the receiving state (Heinitz 2013, 26).

The political security of states can also be threatened when migrants are opposed to the regime of their home country and are involved in anti-regime activities in the host country. These activities may be in conflict with the interests of the receiving states. For example, Palestinian and Syrian refugees are involved in political activities in foreign territories aimed at the governments of Israel and Syria respectively. Thus, migrants and refugees may threaten the political security of their home country by marshalling international public opinion through publicity campaigns aimed at the international community and at particular international institutions.

Finally, a case can be made that the institutions of the state can be threatened by patterns of transnational crime, such as smuggling and human trafficking; especially when women and children are involved.

For much of the 1990s, the concept of trafficking was poorly defined and frequently used as a synonym for smuggling or even illegal migration. Since December 2000, a global definition of trafficking has been available through the signing of the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, which supplements the Convention on Transnational Organised Crime. The Protocol defines trafficking comprehensively: its focus is on coercion for the purpose of exploitation, and it precludes the possibility of legal consent by the victims of traffickers (Laczko 2002). Although in practice there are some problems in distinguishing between trafficking and smuggling, one of the most important results of such a distinction is that it is mainly women and children who are the victims of traffickers (Budapest Group 1999, 15). Frequently, the form of exploitation is forced prostitution or sexual enslavement, but sometimes it is bonded labour, in housekeeping or, for boys in certain Gulf countries, camel jockeying (Heinitz 2013, 30).

Increasingly, Africa is a source region with more clandestine movements, more diverse transit points and complex changing dynamics. From East Africa, young girls and women are trafficked from war zones to the Gulf States (Adepoju 2004). According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), trafficking of women takes place from Ghana to Lebanon and Libya, women for domestic service from Central and West Africa to Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, and even voluntary migrations of women from Ethiopia to the Middle East where working conditions are considered to be virtual slavery (IOM 2001, 2).

Trafficking from South Asia to the Middle East is a serious problem with the region having become a destination rather than a point of transit (IOM 2001, 2). A particular abuse, of young boys trafficked for the violent and dangerous pursuit of camel racing, is documented in Qatar [children from Sudan, Somalia and S. Asia], Kuwait [Sudan, Yemen, Eritrea and S. Asia], and United Arab Emirates [Pakistan and Bangladesh]. In addition, extensive trafficking of children from South Asia and Africa is noted for begging rings in Saudi Arabia (Baldwin Edwards 2005, 19).

Societal Security

Societal security is about the protection of collective identities, such as religions and nations (Buzan 1991, 122–123). If societal security is about the sustainability of particular patterns of religious and ethnic identity and custom, the state-nation building process often aims at suppressing, or at least, homogenising sub-state social identities (Buzan 1991, 73). Since language, religion, and cultural tradition all play their part in the idea of the state, they may need to be ‘defended or protected against cultural imports’ (Olshtain and Horenczyk 2000). Therefore, for Middle Eastern states, such as Lebanon and Iraq which have to address ethnic and religious questions in their state-nation building process, population trends may exacerbate domestic conflicts and societal insecurity. For example, population growth may favour a particular, ‘unwanted’ ethic and religious community. Hence, population patterns may be seen as threatening national security. This is the reason that Lebanese and Iraqi governments are not interested in providing statistics about population composition in Lebanon and Iraq respectively.

In the long term, the most obvious effect of migration is the creation of ethnic minorities in host countries. Admitting migrants has long-lasting social effects on receiving states. It may turn relatively homogeneous societies into multi-ethnic and multicultural ones by the introduction of ethnically and culturally different people. Migrants often raise societal concerns because they are seen as potentially threatening to the popularity and strength of the nation-state. They are also perceived as challenging traditional notions about the meaning of nationality and citizenship and the rights and duties of citizens towards their state and vice versa (Weiner 1992, 110).

It is widely established in people’s minds that the existence of migrants has a substantial impact on social stability and economic prosperity, which are inter-related. The fact that very few states fit the idealised picture of the homogeneous nation-state, and that most states are cultural and social products of earlier movements of people, fails to register on the popular consciousness. Thus, migration in some Arab countries is seen as threatening communal identity and culture by directly altering the ethnic, cultural, religious and linguistic components of the population of the receiving state (Heinitz 2013, 26).

Migrants may be seen as a threat to the cultural norms and value systems of the receiving states. In defending themselves against migrants, national societies may emphasise their differentiation from them. As a result, questions of status and race may be difficult to avoid. Moreover, migration occurs alongside the clash of rival cultural identities. In combination, migration threats and the clash of cultures contribute to a societal conflict between domestic and sending societies (Guild and Selm 2005). As it has already be shown, this conflict may easily feed into a restructuring of relations between the hosting and home states which may, in turn, affect regional and international security.

In addition, the governments of the receiving states are concerned with the migrants’ alleged social behaviour, such as criminality and ‘black labour’ that may generate local resentment and lead to xenophobic popular sentiments, as well as to the rise of anti-migrant political parties that could threaten the government in power. Thus, countries receiving migrants may need to maintain social stability and cohesion in the face of the multi-culturalism produced by migration. It is possible, however, that under certain circumstances, governments may pursue anti-migration policies in anticipation of public reactions.

As the case of the Gulf countries reveals, anti-immigrant feeling and xenophobia also increase in times of recession and high unemployment. Toleration levels are likely to be lower in countries that do not have a tradition of migration and higher in those that have. Migrants who are similar to the host population are also easier to accommodate and tolerate than those that are racially and culturally distinct.

Concomitant unemployment and deficient public services offer fertile ground for superficial but ostensibly pride-restoring rhetoric and solutions. These, whether expressed in radical religious terms, or as attacks against the existing system (or the ‘outsiders’), can be explosive (Abu-Lughod 1983, 237). It may be argued that among the various social problems that the MENA countries face, one of the most important is that of cultural conflict between the nationals of the countries concerned and Western immigrants. Western migration has traditionally contributed to the manpower needed for manufacturing and service industries. However, the demographic evolution of these immigrant communities poses several crucial policy issues for the host countries. As well as adding to the costs of infrastructural and service provision, immigrant communities are increasingly seen as posing a threat to national culture and identity by directly altering the ethnic, cultural, religious, and linguistic components of the population of the receiving countries.

Along with the unprotected status of forced migrants in many countries, the issue of human rights protection of migrants is paramount in the Middle East. Despite some small but welcome improvements at the national level, the situation remains quite problematic. As Jureidini (2004, 209) has shown, ratifications of the principal human rights treaties by Middle Eastern states is quite poor. Thus, there are several millions (presumably) of female migrant domestic workers in the Middle East whose rights are almost non-existent, save under the general provisions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Given the massive reporting of abuses and violence against female migrants in particular, this represents one of the most serious deficits of migrants’ human rights protection anywhere in the world today.

The lack of labour law protection for domestic workers in conjunction with the apparent nexus of trafficking, domestic service and forced prostitution demonstrates the ease with which employers and traffickers can trick and cheat immigrants of their few legal rights. The Arab Charter on Human Rights of the League of Arab States, adopted in 1994, does contain some universal provisions for all persons on the territory – apparently regardless of their legal status or national origin (Baldwin Edwards 2005, 27). However, it also emphasises national law and citizenship as important aspects of economic relations while in practice many signatory states are failing to observe the minimal standards of human rights guaranteed by the Charter.

Economic Security

In the economic sector, one of the main referent objects of security is the economic ability of the state (Buzan 1991, 126). Therefore, in terms of economic security, the importance of demography is highlighted by the effects of demographic growth on the economic capability of the state and how this would affect its socio-political stability (Cammet et al. 2015). Specifically, due to population growth rates that prevail in the Middle East today there would be a need to significantly increase national production to maintain per capita income levels. There would also be a need to increase employment and social overhead capital investments (McKee et al. 2017, 4). These phenomena make the developmental race to catch up with the needs of the region and its population more problematic and, thus feed into greater potential for instability.

Population growth in the Middle East is an important issue with regard to socio-economic development. Depending on issues of economic development, this demographic change can be seen as either a ‘gift or a curse’, since the lower dependency ratio allows a greater working age population to more easily support the elderly. The demographic changes in the Middle East have produced ‘some of the most intense pressures on labour markets observed anywhere in the world in the post-World War II period’ (World Bank 2004, 71). The excess of labour force growth over employment growth has resulted in high unemployment rates (World Bank 2003, 72). Labour force growth is not determined solely by demographic issues, and in fact participation rates (especially female) have been rising continuously. Thus, currently the number of jobs required to absorb the new labour market entrants, and to deal with current unemployment levels is around 100 million. This is effectively a doubling of the current levels of employment, requiring massive labour market and economic reforms. However, in the absence of structural economic change, the demographic shift would probably result in higher unemployment.

Population growth also exacerbates certain societal problems by contributing to lower standards of living as well as to the uneven distribution of wealth (Birdsall, Kelley and Sinding 2001). Poverty, uneven distribution of wealth and lack of access to basic human needs are prime causes of domestic conflicts, especially when relatively poor people see others living much better. Conflict is bound to erupt where basic human needs are not met (Streeten 1981; Burton 1990). Thus, in order to put accumulation on a firm foundation, and to move through demographic transition, Middle Eastern countries must meet the basic human needs of their populations. Economic conditions, however, prevent these states from developing welfare policies since a considerable amount of money must also be invested in improving the infrastructure necessary for economic development.

Population growth in the Middle East is an important issue with regard to socio-economic development, and migration flows add to the pressures associated with it. Migration has dominated the economic landscape of the Middle East for more than 40 years (World Bank 2004; UNDP 2002 and 2003).

It has been argued that migrants in the Middle East threaten the economic stability of the receiving states by imposing limits on their financial capability (Heinitz 2013, 30). Due to their numbers and level of poverty, migrants create a substantial economic burden by straining housing, education, sanitation, transportation, and communication facilities, while at the same time increasing consumption. To deal with this economic burden, the receiving states need to increase taxes paid by their own citizens. Middle Eastern societies, or specific social groups within them, have usually reacted to the influx of migrants for three reasons: first, because of the economic costs the latter impose on the receiving state; second, because of the migrants’ purported social behaviour; and third, because migrants may displace local people in employment because they are prepared to work for lower wages (Baldwin Edwards 2005, 25).

In general, government responses to the challenges posed by the significant number of migrants (especially refugees) have been considerable. Yet the many services needed by refugees, including food, shelter, clothing, health care, schooling and safety, overwhelm governmental capacities and undermine public support, especially in refugee-weary Lebanon and Jordan. With gainful employment and proper schooling difficult to obtain, refugees are often hard pressed to establish a semblance of normalcy (Connor 2016a).

One of the main effects of outgoing migration in the Middle East has been ‘brain drain’. Although migrants’ remittances constitute important contributions to the economy of the sending country, against this has to be balanced the loss – potential or actual – of skilled scientists or younger workers (Wickramasekara 2002, 7). Wickramasekara advocates dual citizenship and recognition of diaspora, in order to promote ‘brain circulation’. For such a circulation, however, specific practices are needed in both sending and receiving countries. These include, for receiving countries: visa regimes, student fee levels, networking with sending countries, and ethical and controlled recruitment campaigns. For sending countries, taxation and human rights problems are clear disincentives, as well as incentives not only to return but also to attract expatriate investments, along with other issues of economic growth and development (Sorensen 2004a and 2004b). This approach is emphasised systematically in UNDP Arab Human Development Reports (2016; 2003; 2002) as well as the World Bank regional employment report (World Bank, 2004).

Environmental Security

Environmental security can be understood in terms of the human impact on the natural environment (Buzan 1991, 131). Demographic growth may have a significant impact on the environment (Murray 1985, 33–34). The reason for this is that the effects of population growth on economic development often lead to excessive pressures on natural resources. Rapid deforestation, desertification, and soil erosion are most acute where population growth and poverty are most apparent. Especially in the Middle East, where a growing population will require increased quantities of elementary goods, which may lead to increased production and a more extensive use of fertilisers and irrigation techniques which may damage the environment.

Central to any analysis of population-environment interaction is the issue of water. The availability of fresh water for both domestic and agricultural use has always been a basic prerequisite for human life and civilisation. But as it was noted above, in no other world region has water availability played such a dominating role in determining the settlement, growth and movement of human populations as it does in the Middle East. The efficient use of the scarce water resource has become a central ingredient of Arab culture and of the structure of Middle Eastern societies and economies. Thus, the precarious balance of water resources in the Middle East is likely to be a sensitive and potentially explosive issue (Naff and Matson 1985; Starr and Stoll 1988).

Today, the growth of large cities in the Middle East and the need for industrialisation have imposed a tremendous burden on the water supply facilities of the urban centres for domestic and industrial use. The increase in population numbers over the last 40 years has meant that such supplies have now become inadequate, and the water catchment in the region has had to be continuously enlarged in an attempt to cope with water demands. Even with these tremendous efforts, it may be said that almost every large city in the Middle East has water supply problems, and that these are likely to increase further.

Water availability is the most important constraint on rural land use in the region and the effects on cultivation are marked. The lack of water resources is likely to be felt most strongly in agricultural areas for two reasons. First, because their production systems lack redundancies that would allow them to adapt to sudden shifts in the amount of water resources available; and second, because they have little access to capital (other than land) that would permit rapid evolution of production strategies. This means that the Middle East economies will be very much affected by possible shortages of water since they are basically agricultural economies.

The human problems engendered by these shifts in water resources would be enormous. Changes in the productivity of agriculture associated with potential and eventual shortages of water resources would lead to massive inland and international migrations that would in turn enhance existing social, economic and other related problems. Moreover, such changes would even lead to intra- or inter-state conflicts that would consequently endanger regional peace and stability. The situation becomes more dramatic if we take into account the high rate of population growth in the region.

Water availability also affects livestock rearing. The type of animals kept in particular areas is related to the amount of precipitation and drinking water to be expected there. Numbers increase in wet years and decrease in dry ones, creating a kind of dynamic equilibrium that is easily upset. The effects of drought and water shortages in such a situation can be devastating.

Related to the problem of water supply is the problem of sewage disposal (Beaumont, Blake and Wagstaff 1988, 107). Human wastes are discharged untreated into the ground or into the nearest watercourse. As a result, the shallow aquifers have become contaminated. Waste and effluent disposal is also causing concern, as the waters of special regions and cities, all of which possess great value from aesthetic, recreational and other utilitarian standpoints, become increasingly polluted.

Conclusion

The population of the Middle East is expected to continue growing in the foreseeable future. This could lead to some problems, as Middle Eastern governments struggle to close the gap between the rich and poor, decrease poverty rates, provide essential necessities (housing, jobs, health care) to their citizens, and develop their countries’ infrastructure. This would require significant investment. Therefore, demographic factors are closely related to the development of the Middle Eastern states and the region as a whole. Moreover, demographic factors have important implications for all security sectors, while security interdependence makes the management of security threats not only challenging but politically imperative. Thus, addressing the impact of current population patterns on Middle Eastern communities, societies and states, as well as managing regional and transnational patterns of conflict and migration in the region is imperative for achieving both domestic security and regional stability.

Recent migration flows in the Middle East have been caused partly by economic reasons (people searching for economic opportunities) but most importantly by regional conflicts resulting in internal displacement and inter/transnational movement. Some states’ responses to these developments are worrisome. For example, countries like Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have placed legal obstacles and physical barriers preventing entry of asylum seekers and refugees as well as returning them involuntarily to their homes or to third countries. Generally speaking, national governments and local populations are loath to accept large numbers of people in great need, who are ethnically different and may pose threats to social stability. Most prefer fewer foreigners crossing their borders given economic uncertainties, record government deficits, high unemployment, growing anti-immigrant sentiment, and concerns about national and cultural identity.

References

Abu-Lughod, Janet. 1983. ‘Social Implications of Labour Migration in the Arab World’. In Arab Resources: The Transformation of a Society edited by Ibrahim Ibrahim, 237–266. London: Groom Helm.

Adepoju, A. (2004). ‘Changing Configurations of Migration in Africa. Migration Information Source’, September 1, 2004. http://www.migrationinformation.org.

Allan, Anthony J. 1993. ‘The Nile: The Need for an Integrated Water Management Policy’. In The Middle East and Europe edited by Gerd Nonneman, 235–244. Brussels: Federal Trust for Education and Research.

Baldwin-Edwards, Martin. 2005. Migration in the Middle East and Mediterranean. Global Commission on International Migration. Athens: Greece, September 2005.

Beaumont, Peter, Blake, Gerald H. and Malcolm J. Wagstaff. 1988. The Middle East: A Geographical Study. 2nd edition. London: David Fulton Publishers.

Beaumont, Peter. 1993. ‘Water: A Resource under Pressure’. In The Middle East and Europe edited by Gerd Nonneman, 183–189. Brussels: Federal Trust for Education and Research.

Beaumont, Peter. 1978. ‘The River Euphrates: An International Problem of Water Resource Development’. Environmental Conservation, 50(1): 35–43.

Beschorner, Natasha. 1993. ‘Prospects for Cooperation in the Jordan Valley Basin’. In The Middle East and Europe edited by Gerd Nonneman, 151–162. Brussels: Federal Trust for Education and Research.

Birdsall, N., Kelley, A., and S. Sinding. 2001. Population matters: Demographic Change, Economic Growth and Poverty in the Developing World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bongaarts, J. and Bulatao, R. 1999. ‘Completing the demographic transition’. Population and Development Review, 25 (3): 515–529.

Budapest Group. 1999. ‘The relationship between organised crime and trafficking in aliens’. Study prepared by the Secretariat, Budapest Group; Vienna: ICMPD

Burton, John, W. (ed.). 1990. Conflict: Human Needs Theory. London: Macmillan.

Buzan, Barry. 1991. People, States and Fear. 2nd edition. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Cammett, Melanie, Ishac Diwan, Alan Richards, and John Waterbury. 2015. A Political Economy of the Middle East. 4th edition. Boulder: Westview Press.

Choucri, Nazli. 2002. ‘Migration and Security: Some Key Linkages’. Journal of International Affairs, 56 (1): 98–122.

Choucri, Nazli. 1997. ‘Demography, Migration and Security in the Middle East’. In The Middle East in Global Change edited by Laura Guazzone, 95–118. London: Macmillan.

Choucri, Nazli and Robert C. North. 1995. ‘Population and (In)security: National Perspectives and Global Imperatives’. In Building a New Global Order edited by David Dewitt, David Haglund and John Kirton, 229–258. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Choucri, Nazli (ed.). 1984. Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Population and Conflict. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Courbage, Y. and P. Puschmann. 2015. ‘Does demographic revolution lead to democratic revolution?’. In Population Change in Europe, the Middle-East and North Africa edited by Matthijs, K., Neels, K., Timmerman, C., Haers, J., and S. Mels, 203–224. Farnham: Ashgate.

Connor, Phillip. 2016a. ‘Middle East’s Migrant Population More Than Doubles Since 2005’. Pew Research Center Reports, 8 October, http://pewrsr.ch/2e2p1Jz.

Connor, Phillip. 2016b. ‘Number of refugees to Europe surges to record 1.3 million in 2015’. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, August.

http://www.pewglobal.org/2016/08/02/number-of-refugees-to-europe-surges-to-record-1-3-million-in-2015/.

Connor, Phillip and Jens Manuel Krogstad. 2016. ‘About six-in-ten Syrians are now displaced from their homes’. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, June. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/06/13/about-six-in-ten-syrians-are-now-displaced-from-their-homes/.

Cooper, C.A. and S.S. Alexander. Eds. 1972. Economic Development and Population Growth in the Middle East. New York: American Elsevier Publishing.

Crane, K., Simon, S., and J. Martini. 2011. Future Challenges for the Arab World. The Implications of Demographic and Economic Trends. Rand Corporation.

Daugherty, Helen Ginn, and Kenneth C. W. Kammeyer. 1995. An Introduction to Population. New York: The Guilford Press.

Fargues, P. 2006. International Migration in the Arab Region: Trends and Policies. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. New York.

Fargues, P. 2008. Emerging Demographic Patterns across the Mediterranean and their Implications for Migration through 2030. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Fargues, P. 1989. ‘The decline of Arab fertility’. Population, 44 (1): 147–175.

El-Khoury, Gabi. 2016. ‘Demographic Trends and Age Structural Change in Arab Countries: Selected Indicators’. Contemporary Arab Affairs, 9 (2): 340-345.

Glazer, Nathan. (ed.) 1991. Glamor at the Gates: The New Migration. San Francisco: ISC Press.

Gillis, John R., Louise A. Tilly and David Levine. Eds. 1992. The European Experience of Declining Fertility, 1850-1970. The Quiet Revolution. Oxford: Blackwell.

Goldstone, J. 1991. Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Grogger, Jeff (1998), ‘Market Wages and Youth Crime’. Journal of Labor Economics, 16 (4): 756–791.

Guild, Elspeth and Joanne van Selm. Eds. 2005. International Migration and Security. London: Routledge.

Gurr, Robert. 1970. Why Men Rebel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Heinitz, Amir. 2013. Migration and Security in the Eastern Mediterranean. Brussels: DCAF.

Heisler, Martin O. and Zig Layton-Henry. 1993. ‘Migration and the Links Between Social and Societal Security’. In Identity, Migration and the New Security Agenda in Europe edited by Ole Weaver, Barry Buzan, Morten Keistrup, and Pierre Lemaitre. New York, St. Martins Press.

Herrera, Santiago and Karim Badr. 2012. Internal Migration in Egypt. Levels, Determinants, Wages, and Likelihood of Employment. World Bank Policy Research Working Papers, No. 6166 (August), http://hdl.handle.net/10986/12014.

Hoel, Arne. 2014. Education in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington: World Bank, 27 January, http://www.worldbank.org/en/region/mena/brief/education-in-mena.

Hussein, S. and Ismail, M. 2016. ‘Ageing and elderly care in the Arab region: Policy challenges and opportunities’. Ageing International. https://www.ilpnetwork.org/wp-content/media/2016/10/Hussein-MENA-ageing-in-ARAB-region-ILPN.pdf.

ILO/International Labour Organization (2017), ‘ILO Labour Statistics’, http://www.ilo.org/global/ statistics-and-databases/lang–en/index.htm.

ILO/International Labour Organization. 2015. Global Employment Trends for Youth. Geneva, ILO.

IOM/International Organization for Migration. 2016. Migration to, from and in the Middle East and North Africa. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

IOM/International Organization for Migration. 2004. Arab Migration in a Globalized World. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

IOM/International Organization for Migration. 2001. Trafficking in Migrants. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Jureidini, R. 2004. ‘Human Rights and Foreign Contract Labour: Some Implications for Management and Regulation in Arab Countries’. In Arab Migration in a Globalized World, 201–215. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Klein, Sidney. Ed. 1987. The Economics of Mass Migration in the Twentieth Century. New York: Paragon House.

Kleinschmidt, Harald. Ed. 2006. Migration, Regional Integration and Human Security. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Kulischer, Eugene, M. 1948. Europe in the Move: War and Population Changes, 1917–47. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kumar, Hari. 2016. ‘Thousands of Indian Workers Are Stuck in Saudi Arabia as Kingdom’s Economy Sags’. The New York Times, 1 August, https://nyti.ms/2tESzopMartin.

Laczko, F. 2002. ‘Human Trafficking: The Need for Better Data’. Migration Information Source, November 1, 2002. Available at: http://www.migrationinformation.org.

Loichinger, Elke, Anne Goujon and Daniela Weber. (2016). Demographic Profile of the Arab Region. Realizing the Demographic Dividend. Beirut: United Nations.

Luy, M. and Gast, K. 2014. ‘Do women live longer or do men die earlier? Reflections on the causes of sex differences in life expectancy’. Gerontology, 60 (2): 143–153.

Malik, Adeel and Bassem Awadallah. 2013. ‘The Economics of the Arab Spring’. World Development, 45: 296–313.

McKee Musa, Keulertz, Martin, Habibi, Negar, Mulligan, Mark and Woertz, Eckart. 2017. Demographic and Economic Material Factors in the MENA Region. MENARA working Papers, no. 3, October 2017.

Mirkin, B. 2010. Population levels, trends and policies in the Arab region: Challenges and opportunities. United Nations Developmental Programme, Regional Bureau for Arab States, Research Paper Series.

Murray, Anne Firth. 1985. ‘Population: A Global Accounting. Environment‘. 27 (11): 11–27.

Naff, Thomas and R.C. Matson. Eds. 1985. Water in the Middle East: Conflict or Cooperation? Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Olshtain, Elite and Gabriel Horenzy. Eds. 2000. Language, Identity and Migration. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Magness Press.

Paasonen, Kari and Henrik Urdal. 2016. ‘Youth Bulges, Exclusion and Instability. The Role of Youth in the Arab Spring’. PRIO Policy Briefs. No. 3/2016.

Philip L. and Froilan Malit. 2017. ‘A New Era for Labour Migration in the GCC?’. Migration Letters 14 (1): 113–126.

Popkin, Barry M., Linda S. Adair and Shu Wen Ng. 2012. ‘Global Nutrition Transition and the Pandemic of Obesity in Developing Countries’. Nutrition Reviews 70 (1): 3–21

Preston, Samuel H., Patrick Heuveline, and Michel Guillot. 2001. ‘Demography: Measuring and Modelling Population Processes’. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers.

Puschmann, P. and Matthijs, K. 2015. ‘The demographic transition in the Arab world: The dual role of marriage and family dynamics and population growth’. In Population Change in Europe, the Middle-East and North Africa edited by Matthijs, K., Neels, K., Timmerman, C., Haers, J., and S. Mels, 120-165. Farnham: Ashgate.

Raphael, Steven and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer. 2001. ‘Identifying the Effect of Unemployment on Crime’. Journal of Law and Economics 44 (1): 259–283.

Rashad, H. 2000. ‘Demographic transition in Arab countries. A new perspective’. Journal of Population Research, 17 (1): 83–101.

Rashad, H. and Khadr, Z. 2002. ‘The demography of the Arab region: New challenges and opportunities’. In Human capital: Population economics in the Middle East edited by I. Sirageldin, 37–49. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Robinson, Vaughan. 1998. ‘Security, Migration, and Refugees’. In Redefining Security edited by Nana K. Poku and David T. Graham, 67–90. New York: Praeger.

Rother, Björn. 2016. The Economic Impact of Conflicts and the Refugee Crisis in the Middle East and North Africa. In IMF Staff Discussion Notes, No. 16/08 (September).

Saxena, Prem C. 2013. Demographic Profile of the Arab Countries: Analysis of the Ageing Phenomenon. Beirut: United Nations, https://www.unescwa.org/node/14882.

Simon, Julian L. 1989. The Economic Consequences of Immigration. New York: Blackwell.

Sorensen, N. N. 2004. ‘The Development Dimension of Migrant Remittances’. Migration Policy Research, IOM Working Paper 1, June 2004.

Streeten, Paul. (ed.) 1981. First Things First: Meeting Basic Human Needs in the Developing Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Starr, J.J. 1991. ‘Water Wars’. Foreign Policy, 82: 17–36.

Starr, J.R. and D.C. Stoll. Eds. 1988. The Politics of Scarcity: Water in the Middle East. Washington D.C.: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Tabutin D. and Schoumaker B. 2012. ‘The demographic transitions: Characteristics and public health implications’. In Public Health in the Arab World edited by Jabbour, S., Giacaman, R., Khawaja, M., and I. Nuwayhid, 35–46. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tucker, Robert, Charles Keelu and Linda Wringley. Eds. 1990. Immigration and the U.S. Foreign Policy. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Tsui, Amy Ong. 2001. ‘Population Policies, Family Planning Programs, and Fertility: The Record’. Population and Development Review 27: 184–204.

UNDESA/United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2015. International Migration Report 2015. New York: United Nations, http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/. migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2015.pdf.

UNDESA/United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2017. World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp.

UNDP/United Nations Development Programme. 2016. Arab Human Development Report 2016. Youth and the Prospects for Human Development in a Changing Reality. New York, UNDP. http://www.arab-hdr.org/reports/2016/english/AHDR2016En.pdf.

UNDP/ United Nations Development Programme. 2003. Arab Human Development Report 2003. NY: United Nations Development Programme.

UNDP/ United Nations Development Programme. 2002. Arab Human Development Report 2002. NY: United Nations Development Programme.

Weiner, Myron. Eds. 1993. International Migration and Security. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Weiner, Myron. 1992. Security, Stability, and International Migration. International Security, 17 (3): 91–126.

Weiner, Myron and Sharon Stanton Russell. Eds. 2001. Demography and National Security. New York: Berghahn Books.

Wickramasekara, P. 2002. Policy responses to skilled migration: Retention, return and circulation. Perspectives on Labour Migration, International Migration Programme. Geneva: International Labour Organization (ILO).

Winckler, O. 2009. Arab Political Demography: Population Growth, Labour Migration and Natalist Policies. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

World Bank. 2004. Unlocking the Employment Potential in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington DC: The World Bank.

World Bank. 2003. Middle East and North Africa Region. Washington DC: The World Bank.

Young, S. 1989. ‘The Battle for Water: Storm Clouds Gathering’. Middle East International, 22 February.

Yount, K.M. and Sibai, A.M. 2009. ‘Demography of aging in Arab countries’. In International Handbook of Population Aging edited by P. Uhlenberg, 277–315. New York: Springer.

Zolberg, Aristide, Astri Suhrke and Sergio Agyayo. 1989. Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Conflict and Migration in the Middle East: Syrian Refugees in Jordan and Lebanon

- Science, Technology and Security in the Middle East

- Introducing Regional Security in the Middle East

- Environmental (In)Security in the Middle East

- Societal (In)Security in the Middle East: Radicalism as a Reaction?

- Economic (In)security and Economic Integration in the Middle East