Capital mobility has been an integral part of the global process of economic development. Quite a number of theoretical ideas which appeal to many disciplines in the social sciences have been put forward which define the relationship between capital mobility and economic development. The initial search shows an established relationship which is more inclined to geographical contexts within which capital flows. This contestation has been aptly trumpeted by Ascani, Cresenzi and Iammarino (2012) who argue that capital mobility crucially sharpen the regional character of development processes, emphasizing the role of geographical proximity in shaping successful economic performance. However, beyond geographical lenses are politics, culture and other sociological vagaries which provide some equally useful insights about the relationship between capital mobility and economic development. Pursuant to this gap there have been attempts in the literature to provide some political economy perspectives to the relationship between capital mobility and economic development which appeals to classical economics and Marxism. Yet, these political economy perspectives have been, in terms of application, limited to the processes with which formal political and economic structures could be seen as central to economic development. What then is left?

Given the fact that political economy thoughts have assumed new directions with arguments which challenge the orthodox strands of political economy namely liberalism and Marxism it is important to highlight these new directions and their implications for political economy analysis of social and economic phenomena particularly, and in the case of the paper, capital mobility. There are gaps that need to be filled in the theoretical literature as far as the understanding of the relationship between capital mobility and economic development. These gaps will be filled by deploying the perspectives to answer the following questions

- What are the developmental outcomes of the mobility of capital which may be found permeating into the economic and political spectra?

- Within which institutional contexts will capital mobility yield favorable outcomes or otherwise?

- What are the organizational sides of the capital mobility?

- What are the structural, yet non-political and non-economic, narratives associated with capital mobility?

- What are the human narratives which work to constrain or facilitate the mobility of capital?

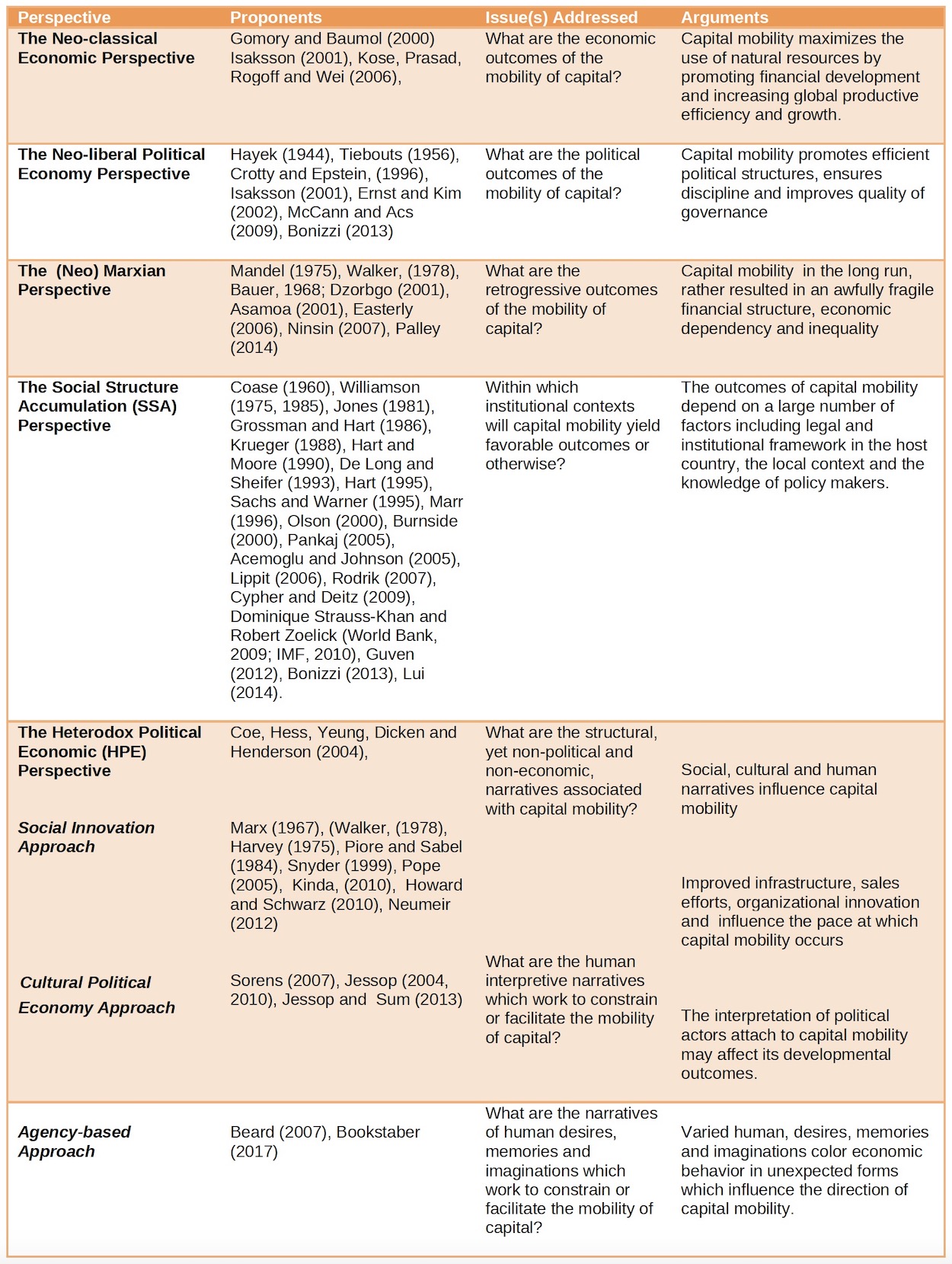

The aim of this paper is to pull all the orthodox and heterodox political ideas which remain sparse and unconnected and synchronize them into a holistic frame of analysis which would deepen the explanation about the texture, direction, quantum and effects of capital mobility in any economic development course. This paper thus brings out five main perspectives in political economy which provides in-depth explanations to the nuances of capital mobility and its nexus with economic development and economic development policy. The paper finally introduces the new approaches which contain new context and correlates through which a complex narrative of the relationship between capital mobility and economic development would be derived. These include: the Neo-classical Economic Perspective; the Neo-liberal Political Economic Perspective; the Marxian Perspective; the Social Structure Accumulation (SSA) Perspective and the Heterodox Political Economic (HPE) Perspective,

This paper is devoted to exclusively present the political economy thoughts which underpin the phenomenon of capital mobility. In this paper I show the proponents, assumptions, focal points, usefulness and the contributions of each perspective to the understanding of capital mobility and its effects on economic development as well as highlighting the strengths and deficiencies to the analysis to capital mobility. This paper is organized into three main sections. It starts with a discussion on the context within which capital mobility is crystallized. This will be followed by an analysis of the stance taken by the proponents of the key orthodox political economy perspectives and how their ideas explain the relationship between capital mobility and economic development. The next section contains deliberations on the heterodox political economy perspectives and how these are interwoven into the capital mobility-economic development nexus. It then concludes with a synthesis of the approaches.

How has Capital Mobility Manifested and Operated?

Historically, the mobility of capital originally motivated by technological advancement particularly the railway industry (Bookstaber, 2107). Subsequently capital mobility occasioned global economic integration process spawned by imperialism and its hand maidens – slavery and colonialism – between the sixteenth century and the mid twentieth century. With the end of the Second World War and the success of the decolonization process which saw many colonies in Asia, Africa and Latin America gaining independence the texture of capital mobility changed from mere investments to foreign aid with all its true essence and character contained in what was to be known as the Marshal Plan. This operated side-by-side with establishment of subsidiaries of privately-owned multinational companies concentrated in European countries and the United States to developing countries mostly within the manufacturing and, in some little extents, the service industries.

However, the 21st century, with its progressively liberalized world order, has been presented with a new trend in the capital mobility enterprise. In recent times, capital mobility has become increasingly privatized and globally financialized, in intensive forms. Financialization presents itself as a pattern of accumulation in which profit making occurs increasingly through financial channels in the operation of the domestic and international economies through the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions (Krippner 2004; Epstein, 2005) Practically, there are new, hybrid relationships between states and businesses, where state funding supports and guides and businesses implement, are of particular interest, as they reveal the emerging ways that expertise, technology, and finance are deployed (Gu et al., 2016; Xiuli et al. 2016) with new roles for the state. Thus, capital mobility has assumed the ‘beyond aid’ reconfigurative character (Scoones, Amanor, Favareto and Qi, 2016).

Another reconfiguration on the capital mobility enterprise is the fact that it is now operating from multiple sources. With the advent of the new and emergent economies and capital hubs known as the BRICS, Lee (2014) observed, that the inclusion of the new sources adding on to such as to US or European countries must be seen in this light; as an extension of capital and markets, with greater diversity and options. Lastly, Moyo, Yeros, & Jha (2012) make new observations about the dynamics of capital mobility concerning the existence of new patterns of accumulation in new sites across the world including Africa in notable areas such as agricultural development, trade, manufacturing and construction.

For developmental purposes the newly configured patterns of capital mobility present a new landscape for development cooperation with greater opportunities for recipient countries to several sources of capital (Kragelund, 2008; Tan-Mullins, Mohan, & Power, 2010; Brown, 2012; Mohan & Lampert, 2013). However, for intellectual purposes, these new patterns also call for analytical frameworks and techniques within which writers would situate the incidence of capital mobility. Practically, it is established in the literature that the capital mobility, and its attendant possibility of generating economic development, occurs through three mediums. The first medium is trade (Coe and Helpman, 1995; Keller, 2002; Bitzer and Geischecker, 2006). The second is through foreign direct investment (FDI) (Aitken and Harrison, 1999; Javorcik, 2004) and the third is personnel or inventor mobility (Almeida and Kogut, 1999; Oettl and Agrawal, 2008). In the literature, proofs are offered about how knowledge diffusion is enhanced by each medium, separately. However, these arguments are limited as they fail to recognize that these mediums can operate simultaneously. They also fail to recognize that the role of these mediums in enhancing capital mobility is more dynamic and complex than the simplistic and isolated manner with which they have been presented.

Kang (2015) corrects the analytical deficiency in the early works on capital mobility – which operates in tandem with knowledge diffusion – by showing the complex and dynamic relationship between the three mediums. Incorporating trade, FDI and inventor mobility and comparing their effects on capital mobility, Kang (2015) makes it evident that FDI and inventors mobility enhance capital mobility but the flow of knowledge reduces when the technological portfolios of two countries are similar.

Comparing the effects of the three mediums, he argues that inventor mobility is the most effective medium for capital mobility when the technological portfolios are of two countries are completely different while trade becomes more effective and balanced when the technological portfolios are completely identical (Kang, 2015). Hence, it is established, as the literature suggests, that the extent to which capital is diffused through these mediums largely depends on the similarities and differences between the geographical areas between which a particular kind of capital is being diffused. Even though Kang analyses the mediums in a more complex fashion he failed to acknowledge the increasing patterns of financialization thereby rendering financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions (Epstein, 2005) as crucial mediums for promoting capital mobility which will be given attention in this paper.

The Political Economy Perspectives

These analytical frameworks draw on five perspectives each of which has its unique set of arguments about capital mobility. Before looking into the essential arguments of these perspectives as they pertain to capital mobility it will be instructive to note, from purely ecological point of view, that development or under development processes may unfold, traditionally, at the local level owing to the availability of resources which may be spatially concentrated. As Levy (2013) stresses, the maximization of these resources leads to economic development of the nation. The role of capital mobility, as Levy (2013) further points out, has proven to be essential to a nation’s ability to yield the maximum potential of its available natural resources. In other words, the emergence of a ‘regional world’ is essentially underpinned by the spatially-bounded localised forces that trigger economic development (Storper, 1997). These resources are natural in essence. Even though Levy and Storper’s argut that capital mobility may yield the maximum potential of available natural resources the process the potential could be realized was not explained. The quest to fill this gap gave rise to the neo-classical perspective to capital mobility.

The Neo-classical Economic Approach

Generally, the conventional neo-classical economic perspective argues that capital mobility, through trade and FDI, maximizes the use of natural resources by promoting financial development and increasing global productive efficiency and growth. Isaksson (2001), on his part, argues from the same neo-classical economic context that capital mobility is by theory, crucial to global resource allocation since it aids to smooth consumption and reduced risk. Isaksson (2001) submits further that capital mobility also allows for investment and economic growth as, in an unrestricted form, it facilitates specialization and production of services to the benefit of the international economy.

However, the strength of the neo-classical economic perspective as an analytical framework has been critiqued by recent empirical data which contradict the assumptions of the perspective. Findings from the works of Gomory and Baumol (2000) and Palley (2008) suggest that FDI and outsourcing, all of which are fostered by capital mobility, may be good for private investors but may be harmful to national income. Furtherance to this, Palley (2009) challenges the functional implication of unrestricted movement of capital suggested early on by Isaksson (2001). Using China as evidence, Palley argues that trade, financial development and FDI also take place even with restricted capital. Besides the neo-classical perspective to capital mobility is deficient because it lacks enough data which present a robust positive relationship between capital mobility and growth (Kose, Prasad, Rogoff and Wei, 2006). Besides this perspective overlooks the extent to which captivity mobility may influence political arrangements. This deficiency is apparently corrected by the neo-liberal political economic perspective.

That capital mobility dominates the policy agenda so completely is indicative of the ideological dimension of the debate. Official policy discussion regarding capital controls and exchange rate regimes has been led by institutions such as the International Monetary fund (IMF), the World Bank, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). These organizations are peopled by high-paid international bureaucrats drawn from around the world, who own global investment portfolios, and have homes and family in more than one country. Adopting a strictly neoclassical standpoint suggests these bureaucrats have a strong private interest in capital mobility, which likely taints the advice these institutions provide. That alone is grounds for fresh public debate over capital controls bringing in the neo-liberal political economic approach.

The Neo-liberal Political Economic Approach

The neo-liberal political economy perspective presents a relationship between the economy and the political institution and shows how economic arrangements affect the political organization. As Hayek (1944) mentioned capital mobility does not just enhance freedom but also helps to protect personal freedom by disciplining governments. Narrowing down to capital mobility as the specific economic arrangement in question the neo-liberal perspective argues that it creates a competitive market sanity that improves the quality of governance. As found in the works of Tiebouts (1956) countries are disposed to improve the quality of governance if they realize that capital is being exiting into other countries with better system of governance. In effect, the exit right of capital confers on it the power not only governments; but it changes policy and the structure of economy (Crotty and Epstein, 1996). Palley (2009) argues that capital controls can contribute significantly to economic stability and create important space for autonomous national economic policy. ); financial liberalization policies in terms of the asset risk/characteristics, the liability and cash flows structure, their “risk appetite” and decision mechanisms (Isaksson 2001, Bonizzi, 2013), and international investment (McCann and Acs, 2009). As a matter of fact, international capital mobility has increased notably in the past decades: on the one hand, the dispersion of international investments across different countries has increased; on the other hand, it tends to concentrate in a few regions within these. Locations where MNEs invest thus become part of global production networks (GPN) at different stages of the production process (Ernst and Kim, 2002).

The Neo-Marxian Approach

Questions about the superficial functionality of globalization by neo-liberal economists and neo-liberal political economists had been raised by many decades ago in Marxist and Neo-Marxist analyses of imperialism (i.e. Slavery, colonialism and neo-colonialism) using them as sources of uneven territorial development among countries. In the words of the Marxists globalization may not be essentially beneficial for some territories due to exploitation of one territory by another territory. Unlike the neo-liberals who argue that capital mobility promotes vibrant competition among governments which then results in efficiency in governance and policy, the neo-Marxists see that capital mobility may run the economies of countries down which Palley (2009) describes as a “race to the bottom” (p.11). Palley (2014) further maintains that even though financial deregulation aided in fill the capita demand gap it lasted a short while. Indeed to Palley (2014), the financialization, in the long run, rather resulted in an awfully fragile financial structure, which found expression in the 2007‒08 financial crisis

Even though a bulk of literature supports these Marxist views thereby making them useful theoretical tools for analyzing development process in developed and developing countries the trajectories about uneven development in the 1970s and beyond have exposed weaknesses in the Marxist theoretical framework. Indeed the theory is no longer apt in analyzing development processes perhaps not only because of its monocausal character as Mandel (1975) argues but also because it is unable to distinguish among separate forces operating simultaneously (Walker, 1978). In other words, even though capital mobility may operate as an isolated force in creating unequal relations between developed and developing countries Marxists failed to isolate the actual role of capital mobility in the unequal relations in their analyses. Isolating the role of capital mobility Walker (1978) tries to correct the deficiency in the Marxist thought by suggesting that capital may use a location as a strategy against labour with local development becoming more dependent on outside capital as development comes in and goes out with capital generating a permanent reserve of stagnant places. However, Walker’s argument does not necessarily correct the deficiency in full.

A review of the arguments of the neo-liberals and the Marxists has clearly showed the contrasting positions taken by each perspective. However, the arguments, in the remits of Social Structure Accumulation approach, are far beyond these two contrasting view points. Invariably, other issues are left unmentioned. In addition, the neo-Marixist and the neo-liberal perspectives have shown fundamental flaws in their analyses of the role of capital in economic development. These perspectives suffer from the tendency to exogenize indigenous social structure of countries receiving the capital. Besides, they fail to contextualize the effectiveness of capital mobility to its appropriateness to local institutions of recipient of capital.

Thus, broadening the scope in the neo-liberal and Marxists analyses of capital mobility, the neo-Marxian Social Structure of Capital Accumulation (SSA) believes that institutional arrangements and rules developed by political actors affect the cost and benefit of policy options. In this regard some new political economy ideas have been introduced in the literature giving rise to the neo-Marxian social structure accumulation approach.

The Social Structure of Accumulation Approach

The focus of SSA theory is on the institutional arrangements that help to sustain what Lippit (2006) describes as “long wave upswings”. The SSA approach suggests that firms which move capital from one geographical area to another use the threat of withdrawing their reduced standards that are socially and legally sought-after. Palley (2009) reiterates the views of the neo-Marxists by arguing that the situation of unrestricted competition between firms produces a prisoner’s dilemma evident in “uncooperative” equilibrium that leaves firms worse off thereby calling for capital control as a mechanism for prevention of unwarranted competition.

According to him, whether such controls are well or poorly used depends on the quality of governance. Neo-liberals tend to automatically assume they will be used badly and make that assumption a centerpiece of opposition against capital controls. He contends that a combination of democratic transparent accountable government, a professionalized civil service, and strong civil society can ensure that capital mobility controls are used well. The neo-liberal concern with regulatory capture is real, but the answer should be the promotion of effective governance rather than abandonment of important policy tool. However, like North (2005), the contemporary literature has not attempted to determine the relative roles of institutions supporting private contracts (“contracting institutions”) and institutions constraining government and elite expropriation (“property rights institutions”). It is in this regard that Acemoglu and Johnson (2005) suggest that property rights institutions have a first-order effect on long-run economic growth, investment, and financial development.

Following these arguments other writers have documented the importance of a “cluster” of institutions that include both contracting and private property protection elements, despite the existence of well-established theoretical arguments emphasizing each set of institutions. For example, the contract theory literature, starting with Coase (1960) and Williamson, (1975, 1985) links the efficiency of organizations and societies to what type of contracts can be written and enforced and thus underscores the importance of contracting institutions (see Hart and Moore 1990; Hart 1995). In contrast, other authors emphasize the importance of private property rights, especially their protection against government expropriation (De Long and Shleifer 1993; Olson 2000).

The centrality of institutions in the discussion on capital mobility and economic development has been promoted in diverse ways by leading to two strands of political economy described by Thomas (2011) as ‘The New Political Economy’ anchored on the works of Sachs and Warner (1995) as well as Cypher and Deitz (2009). The proponents of ‘The New Political Economy’ believe that the state must be a maximizer by rationally setting “minimalist’ institutional policies and allowing the natural forces in the economic order operate within the remit of trade and investment. The second is Moderate Institutionalism inspired by the works of Krueger (1988) and Rodrik (2007). Subsequently, the works of Bonizzi (2013) has given refreshing lights on the role of regulation in promoting capital mobility. As a sequel to these entire works there has been a growing consensus among economists, political scientists and sociologists that the broad outlines of North’s story are correct in the social, economic, legal, and political organization of a society, that is, its “institutions,” are the primary determinant of economic performance.

Showing the relevance of the SSA approach to foreign aid, – another means through which capital mobility is crystallized, – new versions of analysis have emerged which has many appeals to this approach. For example, following the failure associated with the overemphasis on neo-liberalism, Dominique Strauss-Khan and Robert Zoelick mentioned the need for renewed understanding of current challenges and the introduction of a new paradigm (World Bank, 2009; IMF, 2010). In line with this philosophical frame, Guven (2012) locates the right diagnostic spot by recommending that the demand side of the lending relationship deserves consideration by focusing on the Fund and the Bank’s borrowers or the recipient countries and the quality of their institutions. This recommendation re-echoes some earlier recommendations by two models known as the socio-economic model and the political model. The socio-economic model recommends the need to introduce friendly packages that acknowledge the social structure and the socio-economic conditions of recipient countries (see Bauer, 1968; Dzorbgo, 2001; Asamoa, 2001, Easterly, 2006; Ninsin, 2007). The political model, on the other hand, acknowledges the importance of political institutions in ensuring the effectiveness of capital mobility. This model calls for efficient political structures which offer credible governmental commitments of the recipient country as they implement IFI policy-related loans (Marr, 1996; Burnside, 2000; Pankaj, 2005).

The SSA approach has been rightly used in the works of Liu (2014). In his work, the role of capital mobility in economic development, using the agricultural sector as a case in point, presents readers with information about the dynamic and complex range of outcomes which emerge from capital mobility in various forms, levels and scopes. Liu’s (2014) examination of the role of capital mobility brings to the fore an explicit claim that capital mobility can potentially generate various types of benefits for the agricultural sector of the host country such as employment creation, and better access to capital and markets for actors in the agricultural sector.

Furtherance to his assertion, Liu (2014) hinted that whether this objective can be met will depend on a large number of factors including legal and institutional framework in the host country, the local context and the knowledge of policy makers. These, according to Liu, are the ingredients which may enable investors to direct capital into the right kind of projects. Liu (2014) argues that the nature and degree of impact of capital mobility on a country or local community’s economic development are largely determined by the following factors:

- Local cultural context

- Good governance

- Involvement of the local stakeholders

- Formulation and negotiation process

- Content of investment contracts

- Profile of investors

- Support from third parties

However, the issues regarding the interpretations people attached to the capital mobility, the threats and the implications of the capital mobility for the politics of agricultural sector development remain unexplained by the neo-classical, neo-liberal, the neo- Marxian and the SSA perspectives. In addition to this critique, the SSA model, specifically, suffers from the tendency to perceive the political structures as merely reactive to capital mobility; assuming that capital will be effective if political structures promote private property rights, competitive market and contract enforcement. Additionally, the model suffers from the tendency of falsely perceiving capital mobility as value-neutral and that it causes harm only when political institutions fail. Such a false perception has been uncovered by studies which suggest that capital causes more harm than good irrespective of the effectiveness of political institutions (see Boone, 1996; Svensson, 2000; Vreeland, 2003; Remmer, 2004; Lal, 2006; and Sorens, 2007). In other words, capital mobility is essentially value-laden.

In addition, the SSA approach, according to Sorens (2007), suffers from the tendency to exogenize the actions of state actors and the subjectivities that underline these actions; thereby falsely assuming that “government actors are beyond the mechanisms of maximization that drive market actors” (p.1). Besides, the socio-economic model displays another striking deficiency by failing to contextualize the effectiveness of capital mobility to its appropriateness to local institutions. In other words, they assume foreign aid is effective only if it is suitable for local institutions and social structures.

These deficiencies found in the neo-Marxist, the neo-liberal perspective and the Marxian social structure accumulation approach have been corrected by the new political economy insights which introduce some amount of heterodoxy in the analysis of capital mobility, in particular, and development discourse in general.

The Heterodox Political Economic (HPE) Perspective

Heterodox political economy perspective makes a case for the role of other institutions and other social arrangements which are neither essentially legal nor economic nor political. Hence, the heterodox political economy perspective holds the view that the role of globalization expressed in capital mobility as a tool for reengineering regional economic development processes is habituated in social conditions. The political economy heterodoxy becomes useful as it comes in the wake of Palley’s (2009) argument that capital mobility has become today’s [political] economic orthodoxy, yet the pure economic case for capital mobility is amazingly flimsy. This perspective suggests that geographical economic development may rely not only on the availability of natural resources, economic and political factors. Rather, improved infrastructure such as development of transportation and communication systems may influence the pace at which capital mobility occurs and eventually affect regional economic development process (Marx, 1967; Kinda, 2010).

Extending its scope, this perspective further notes that enhancement of capital mobility is equally hinged on the non-physical aspects. In the literature it is apparent that fast-growing locations are not closed and independent economies, but rather they are, most likely, those area hosting MNEs having financial capabilities ranging from their sales efforts to reduced turnover time on fixed capital (Harvey, 1975) as well as organizational innovation (Walker, 1978; Howaldt and Schwarz, 2010; Neumeir, 2012) all of which crucially connect the region with foreign markets and resources.

Beyond the organizational novelties, social processes are equally involved in the spread of particular means of production and patterns of consumption (Snyder, 1999). Thus, the spread of globalization through capital mobility may be contingent on social conditions as well. As Piore and Sabel (1984) contend flexible specialisation, trust and face-to-face social relations are fundamental requirements for regional economic success in an era of global economic expansion spawned by capital mobility.

It is therefore clear that the mobility of capital and its improvement thereof are hinged on a deep interrelationship between both physical and non-physical factors cutting across economic, political and social spectra. Following are some research works which bring out how some key social ingredients which may influence the extent to which capital may flow and its possible implications for economic development.

First, the political economy heterodoxy of capital mobility is also understood in the works of Pope (2005). Pope provides a complex analysis on how capital mobility flows into the tourism sector which she refers to as the ‘dollars-only economy’ in Havana which, she discovered, was influenced by race and class. Pope’s study brings the gender dimension into play as shows how crucial it is in influencing the flow of capital in terms of which women’s bodies, and not just sex workers’ bodies, have been ‘commodified’ for personal, and even national, economic gain. Hence, at the center of the capital mobility-development nexus are the issues of class, race and gender.

In the works of Sorens (2007) much emphasis is displayed on how subjectively inclined actions and inactions of political leaders can either expose a country to or keep it unscathed from the challenging outcomes of the conditionalities associated with capital mobility (financial aid) from IFIs. In other words, the interpretation political actors attach to capital mobility may affect its developmental outcomes.

Jessop (2010) brings extended aspect of the interpretative aspect of the political economy heterodoxy earlier on mentioned in the works of Sorens. At the core of his political economy heterodoxy, similar to Sorens’, is the political economy of interpretation or what he refers to as Cultural Political Economy (CPE). It is that aspect of heterodox political economy approach that relishes the inherent subjectivities of not only economic actions and phenomena but political structures and institutions. As a very recently introduced analytical approach, cultural political economy tries to synthesize contributions from the critical political economy and the critical analysis of discourse which are usually employed in the field of policy studies. As found in his works, Jessop (2004, 2010, 2013) have provided rich exhibitions to such synthesis. The notable one among the works with Sum is their most recent book titled “Towards a Cultural Political Economy: Putting Culture in its Place, and “Critical semiotic analysis and cultural political economy” (2013). Generally, the works show how the culture of interpretations plays out in the political economy of development. In effect, the focal point of cultural political economy is the incorporation of interpretations, as found policy discourses as well as political and economic imageries, in the analysis of how strategies and projects are institutionalized.

CPE’s focal point for political economy enquiry is largely drifted to the study of pre-existing interpretations their translation into hegemonic strategies and projects, and their institutionalization into specific structures and practices. Jessop and Sum highlight the relevance of the cultural dimension (understood as semiosis or meaning making) in the interpretation and explanation of the complexity of social formations such as policies. This clearly suggests that policy formulations are supposed to be undergirded by interpretations.

The primacy of interpretations as the foundation of Jessop’s political economy heterodoxy produces a number of assumptions. First, he assumes that policies always reflect selective interpretations of the nature of problems, character of events, explanations of their cause, the anticipated effects, and preferred solutions. Jessop’s evolutionary fervor leads him to argue that all institutional transformations can be explained by the iterative interaction of material and semiotic factors through three mechanisms he mentions as variation, selection and retention. It implies that the role of capital mobility in influencing economic development will be facilitated or hampered by the constructed interpretations of the political and economic actors about the policies that would either sustain or prevent capital mobility.

The main contribution of the CPE approach in the analysis of economic development policy, as promoted by capital mobility, is the need to take seriously the importance of the mobilization of policy ideas, and the perceptions of political and economic actors, in the description and explanation of phenomena [in this case capital mobility] policy dynamics and policy outcomes. The perspective introduced by Jessop would have massive implications for usefulness to economic development planning to him by paying specific attention to the role of a particular set of policy actors (policy advisers, knowledge-brokers, industry players and think tanks) and the mechanisms of persuasion and construction of meaning (soft power) that the use to influence the perceptions of other actors. The CPE encourages that policy makers and policy actors in general, need to selectively attribute meaning to some aspects of the world rather than others and engage with pre-existing interpretations of the problems and solutions available to them in the decision-making process.

All such established perspectives and approaches fail to explain and predict essential and uncertain crises and changes relative to capital mobility. Classical and neo-classical perspectives were unable or refused to predict the crises of inequality associated with the industrial revolution as well as the crises of unemployment and job losses associated with the increased ‘financialization’ of the global economic order. This has given rise to a new approach as the agency-based approach which equally operated within the realm, of political economy heterodoxy

The agency-based approach recognizes that capital mobility may be constrained by financial crises leading to some developmental challenges. As assessment of the financial crises that may constrain capital flow shows how everyday interactions, radical uncertainty, and limited human anticipation capacities combine to create sudden financial chaos. An understanding of capital flow may have to be understood in agent-based approach found in the works of Bookstaber’s (2017) End of Theory which argues that varied human memories and imaginations color economic behavior in unexpected forms may facilitate or impede capital mobility.

The flow of capital and its usage goes beyond interpretations and focus on human reminiscences and imaginations. Earlier, Beard’s (2007) political economy analysis of capital mobility and its attendant implications for development in his book The Political Economy of Desire: International Law and the Nation State had been situated within the context of desire. In her analysis, she views the concept of development, within the context of western culture, as a symptom of loss within the ‘desire for completion’. In her seminal write up it would be argued that capital mobility is a function of the desire for the use of capital as means to engage in economic restructuring of nations hence the desire to see underdeveloped countries experience economic development is revealed as the function of the flow of capital from one society to the other. Though both the CPE approach and the agency-based approach embrace the human narrative the agency-based approach expands the CPE approach in great respects.

Synchronizing the political economy approaches related to capital mobility and economic development Coe, Hess, Yeungt, Dicken and Henderson (2004) assert that economic development is not a product of inherent regional advantages alone. Neither is regional development a mere function of “rigid configurations of globalization process” (p.469). Rather, as mentioned by Henderson, Coe, Hess, Yeung, and Dicken (2002), the role of capital mobility depends on the suitable or inhibiting social, cultural, human, political and economic conditions that may exist in the host country and the original source of the capital. Table 1 shows a summary of the proponents and the arguments of the various perspectives and the main issues they address.

Table 1: Arguments of the Political Economy Perspectives

Conclusion: Synthesis of the Perspectives

Given the fact that capital mobility plays a crucial role in shaping economic development processes indeed the traditional idea that lends credence to the role geographical mobility cannot be ruled out. However, it apparent that it is not geographical proximity per se that causes growth, but it is an important factor shaping the location behaviour of economic agents as well as the intensity of linkages between them. Thus, in this paper, I sought to bring out the political economy perspectives that would provide a detailed insight about the dynamics surrounding the capital mobility-economic development nexus.

Indeed capital mobility may have some favourable economic and political outcomes. Nevertheless, Capital mobility may have both threatening and challenging outcomes. Beyond the role of geographical proximity, the social structure and the quality of the institutions play very crucial roles in determining the flow of capital to recipient societies and the outcomes theoreof. To a very large extent the recipient country’s ability to alter the learning process in the face of changing developmental objectives and opportunities as well as the political decisions may determine that society’s ability to make economic gains out of its integration into the orbit of global economic exchanges. At this point it will suffice to argue that the role of capital mobility in economic development may depend on how global production and distribution networks and regional assets are coupled to stimulate value capture, value creation and value enhancement of commodities and services.

It is important to create a more dynamic political economy framework within which capital mobility-economic development will be analysed at a time when capital mobility is becoming more nuanced and complex in terms of geographical origin and destinations, actors and the intentions. This calls for introduction of new approaches to the already existing orthodox (classical, neo-liberal and the Marxist) and social institutional approaches (New Political Economy and Moderate Institutionalism). The new approaches provide a synthesized political economy approach which appeal to sociological, political, economic and geographical intuitions, in terms of which capital mobility could be largely recognized as a relational and interdependent process involving a combination of the opportunities which the global economic arrangements will present and the character of local institutional arrangement in the region in adapting the real opportunities which may produce what they refer to as interactive effects. Besides, the inclusion of these new approaches to the orthodox approaches enriches the quality and strength of the analytical tools which explain the complexities in the reconfigured capital mobility regime.

Hence, the extent to which capital is moved about into a host society and their implications thereof is determined by a host of natural, political, social, cultural, economic as well as human (desires, interpretations, memories and imaginations) forces which could be regulatory and non-regulatory, tangible and intangible a well as structural and interpretative in character. For this reason, none of the political economy perspectives is capable in answering all questions related to capital mobility the analytical deficiency each may possess. Indeed the ability of a perspective to explain an issue related to capital mobility depends on the assumptions which emerge from the aspects of capital mobility a proponent of a perspective may choose to discuss. However, given the complex narrative associated with the capital mobility and economic development it will be important to synthesize the political economy theories and approaches into a coherent whole to create a more nuanced picture.

On this score, a holistic approach to the discussion of capital mobility would require a synthesized perspective which recognizes the role of structural and human narratives as ingredients that shape the texture, direction, quantum and effects of capital mobility in any economic development trajectory.

References

Acemoglu, D. & Johnson, S. (2005). Unbundling Institutions. Journal of Political Economy, 113(5), 949-995.

Aitken, B. & Harrison, A. (1999). Do Domestic Firms Benefit from Direct Foreign Investment? Evidence from Venezuela American Economic Review. 89(89), 605-618

Almeida, P. & Kogut, B. (1999). Localization of Knowledge and Mobility of Engineers in Regional Networks, Management Science, 45(7), 905-917

Asamoa, A.K. (2001). Depeasantization of Africa’s Rural Economy: The Ghanaian Experience, Accra, Woeli Publishing Services.

Ascani, A. Cresenzi, R. & Iammarino, S (2012). Regional Economic Development: A Review, SEARCH Working Paper, European Commission.

Bauer, P.T. (1959). United States Aid and Indian Economic Development. American Enterprise Association.

Beard J. (2007). The Political Economy of Desire: International Law and the Nation State. Taylor and Francis

Bitzer, J. & Geischecker, I. (2006). What Drives Trade-related R&D Spillovers and Growth? Economics Letters, (85) 209-213.

Bonizzi, B. (2013). Capital Flows to Emerging Markets: an Alternative Theoretical Framework. SOAS Department of Economics Working Paper Series, No. 186, The School of Oriental and African Studies.

Bookstaber, R. (2017). The End of Theory: Financial Crises, the Failure of Economics and the Sweep of Human Interactions. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Boone P. (1996). Politics and the Effectiveness of Foreign Aid, European Economic Review, 40(2), 289-329.

Burnside, C. & Dollar, D (2000). Aid, Policies, and Growth. American Economic Review, 90(4), 847-68.

Coase, R. H. (1960). The Problem of Social Cost. Journal of Law and Economics, (3) 1-44

Coe D, Hess M. Yeung, H.W-C. Dicken P & Henderson J (2004). Globalizing Regional Development: A Global Production Network Perspective. Royal Society of Geography, NS. 29, (pp.468-490).

Coe D. & Helpman E., (1995). International R&D Spillovers. European Economic Review, 859-887.

Crotty, J. & Epstein, G (1999). A Defense of Capital Control in the Light of the Asian Financial Crisis. Journal of Economic Issues, 33(2), 118-149.

Cypher, J. M. & Dietz, J.L (2009). The Process of Economic Development (3rd ed), Routledge, New York.

De Long, J. Bradford & Shleifer, Andrei (1993). Princes and Merchants: European City Growth before the Industrial Revolution. The Journal of Law & Economics, 36(2) 671-702.

Dzorgbo, D-B.S. (2001). Ghana in Search of Development: The Challenge of Governance, Economic Management and Institution Building. Aldershot, Burlington: VT Ashgate Publisher; ISBN: 07546 1211 2

Easterly, W. (2006). Why Doesn’t Aid Work? Retrieved from http://www.cato-unbound.org.

Epstein G.A. (2005). Financialization and the World Economy. Retrieved from https://www.peri.umass.edu/fileadmin/pdf/programs/globalization/financialization.

Ernst D. & Kim L. (2002). Global production networks, knowledge diffusion, and local capability formation. Research Policy, 31(2), 1417-1429.

Gomory, R.E. & Baumol, W.J. (2000). Global Trade and Conflicting National Interest. Cambridge, MIT Press.

Gu, J., Zhang, C., Vaz, A., & Mukwereza, L. (2016). Chinese State Capitalism? Rethinking the Role of the State and Business in Chinese Development Cooperation in Africa. World Development, .81(1), 24–34.

Güven, A. B. (2012). The IMF, the World Bank, and the Global Economic Crisis: Exploring Paradigm Continuity Development and Change 43(4), 869–898.

Hart, O. (1995). Firms, Contracts and Financial Structure. Oxford: Oxford Press.

Hart, O. & Moore, J. (1990). Property rights and the nature of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 98(6), 1119-1158.

Harvey, D. (1975). The Geography of Capitalist Accumulation: A Reconstruction of the Marxian Theory Antipode, 7(2), 9-21.

Hayek, F. (1944). The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Henderson, J., Coe, N., Hess, M., Yeung, H.W-C., & Dicken P (2002). Global Production Networks and the Analysis of Economic Development. Review of International Political Economy, 9(2), 436-64.

Howaldt, J. & M. Schwarz (2010). Social Innovation: Concepts, Research Fields and International Trends. Retrieved from http://www.internationalmonitoring.com/fileadmin.

IMF (2010a). Proceedings from a Press Conference by International Monetary Fund Managing Director ’10. Dominique Strauss‐Kahn, Washington, DC.

Isaksson, A. (2001). Financial Liberalisation, Foreign Aid and Capital Mobility: Evidence from 90 Developing Countries. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 11(1), 309-338.

James, R.V. (2003). The IMF and Economic Development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Javorcik, B.S. (2004). Does Foreign Direct Investment Increase the Productivity of Domestic Firms? In Search of Spillovers through Backward Linkages. America Economic Review, 94(3), 605-627.

Jessop, B. (2004). Critical Semiotic Analysis and Cultural Political Economy. Critical Discourse Studies, 1(2) 159–174.

Jessop, B. (2010). Cultural Political Economy and Critical Policy Studies. Critical Policy Studies, 3(3–4), 336–356.

Kang, B. (2015). What Best Transfers Knowledge? Capital, Goods, and Innovative Labour in East Asia, Institute of Developing Economies Discussion Paper, No. 538.

Keller, W. (2002). Trade and transmission of Technology Diffusion as Measured by Patent Citations. Economic Letter, 87(1), 5-24.

Kinda, T. (2010). Increasing Private Capital Flows to Developing Countries: The Role of Physical and Financial Infrastructure in 58 Countries, 1970-2003. Applied Econometrics and International Development, 10(2), 57-73.

Kose, M.A., Prasad, E., Rogoff, K. & Wei, S. (2006). Financial Globalization: A Reappraisal. IMF Working Paper WP/06/189.

Kragelund, P. (2008). The Return of Non‐DAC Donors to Africa: New Prospects for African Development? Development Policy Review 26(5), 555-584.

Krippner, G. (2004). What is Financialization? mimeo, Department of Sociology, UCLA.

Krueger, A. (1988). The Political Economy of Control: American Sugar. National Bureau of Economic Research: Working paper, No.2504.

Lal, D. (2006), Reply to Easterly: There Is No Fix for Aid. Cato Unbound. Retrieved from www.cato-unbound.org.

Levy, B. (2013). The Role of Globalization in Economic Development. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract.

Lippit, Victor D. (2006) Proceedings from conference on Growth and Crises: Social Structure of Accumulation Theory and Analysis ’06: National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland.

Liu, P. (2014). Impacts of Foreign Agricultural Investment on Developing Countries: Evidence from Case Studies. FAO Commodity and Trade Policy Research Working Paper No. 47. Rome: FAO

Mandel, E. (1975). Late Capitalism. London: New Left Books.

Marr A. (1996). Conditionality and South-East Asian Adjustment. Working Paper 94, Overseas Development Institute, Regent College, London

McCann P. and Acs Z. (2009). Globalization: countries, cities and multinationals. Jena Economics Research Papers, (42).

Mohan, G. & Lampert, B. (2013) Negotiating China: Reinserting African Agency into China–Africa Relations. African Affairs, 112(446), 92–110.

Moyo, S., Yeros, P & Jha, P. (2012). Imperialism and Primitive Accumulation: Notes on the New Scramble for Africa, Agrarian South. Journal of Political Economy, 1(2), 181-203.

Neumeier, S, (2012). Why Do Social Innovations in Rural Development Matter and Should They be Considered More Seriously in Rural Development Research? Proposal for a Stronger Focus on Social Innovations in Rural Development Research. Rural Sociologica, 52(1), 49-69.

Ninsin, K. A. (2007). Markets and liberal democracy. In Boafo-Arthur, K. (Ed.), Ghana: One Decade of a Liberal State, CODESRIA (86-105). Dakar, Senegal.

Oettl, A. & Agrawal, A. (2008). International Mobility and Knowledge Flow Externalities. Journal of Internal Business Studies, 39(8), 1242-1260.

Olson, M. (2000). Power and Prosperity: Outgrowing Communist and Capitalist Dictatorship. New York. Basic Books.

Palley, T.I. (2008). The Economics of Outsourcing: How Should Policy Respond? Review of Social Economy, 66(3), 279-95.

Palley, T.I. (2009). Rethinking the Economics of Capital Mobility and Capital Controls. Revista de Economia Politica, 29(3).

Palley, T.I. (2014) Financialization: The Economics of Finance Capital Domination., New York. Palgrave Macmillan.

Pankaj, A. K. (2005). Revisiting Foreign Aid Theories. International Studies, 42(2), 103-121.

Piore M. & Sabel C. (1984). The Second Industrial Divide. New York: Basic Books.

Pope, C. (2005). The Political Economy of Desire: Geographies of Female Sex Work in Havana, Cuba. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 6(2), 99-118.

Power, M., Mohan, G. &Tan-Mullins, M. (2012) China’s Resource Diplomacy in Africa: Powering Development? Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Remmer, K. L. (2004), Does Foreign Aid Promote the Expansion of Government? American Journal of Political Science, 48(1), 77-92.

Rodrik, D. (2007). One Economics, Many Recipes: Globalization, Institutions and Economic Growth. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press.

Sachs, J. & Warner, A. (1995). Economic Reforms in the Process of Global Integration. Brookings Paper on Economic Activity, 3(3), 103-117.

Scoones, I., Amanor, K., Favareto, A. & Qi, G. (2016). A New Politics of Development Cooperation? Chinese and Brazilian Engagements in African Agriculture. World Development, (81), 1–12.

Snyder, F. (1999). Governing Economic Globalization: Global Legal Pluralism and European Union Law, European Law Journal, Special Issue on ‘Law and Globalisation‘, 5(4), 334-374.

Sorens, J. (2007). Development and the Political Economy of Foreign Aid, Independent Institute. Retrieved from http://www.independent.org/students/essay/essay.asp?id=2043

Storper, M., (1997). The Regional World: Territorial Development in a Global Economy. New York: The Guilford Press.

Sum, N. L. & Jessop, B. (2013). Towards a Cultural Political Economy: Putting Culture in Its Place. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Svensson, J. (2000), Foreign Aid and Rent-Seeking. Journal of International Economics, 51(2), 437-61.

The IMF, the World Bank, and the Global Economic

The IMF, the World Bank, and the Global Economic

The IMF, the World Bank, and the Global Economic

The IMF, the World Bank, and the Global Economic

Tiebout, C.M. (1956). A Pure Theory of Local Public Expenditure. Journal of Political Economy, 64(1), 416-24.

Vreeland, J. R. (2003), Why Do Governments and the IMF Enter into Agreements: Statistically selected case studies. International Political Science Review, 24(3), 321-43.

Walker, R.A. (1978). Two Sources of Uneven Development under Advanced Capitalism: Spatial Differentiation and Capital Mobility. Review of Radical Political Economics, 10(3), 28-37.

Williamson, O. E. (1975). Transaction-Cost Economics: The Governance of Contractual Relations. Journal of Law and Economics, 22(2), 233-261.

World Bank (2009a). Proceedings from the Annual Meeting of the Board of Governors of the World Bank Group ’09: The World Bank Group beyond the Crisis. Remarks of Robert B. Zoellick, President, The World Bank Group, Istanbul, Turkey.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Class Matters: Global Capital Mobility and State Power in Emerging Economies

- Evolutionary Economics and the Question of Corporate Power

- The International Political Economy of Health: The Covid-19 Vaccine Distribution

- Climate Change, Human Mobility and Feminist Political Economy

- Forty Years of Constructing Development: How China Adopted GDP Measurement

- The New EU-Mercosur Trade Agreement: a New Breath to Free Trade