This is an excerpt from Sexuality and Translation in World Politics. Get your free copy here.

In[1] the summer of 2016, I went inside a small café to talk to the owners about a local LGBT[2] campaign: ‘Excuse me, do you know what LGBT means?’ They didn’t. I tried again, asking about sekushuaru mainoriti[3], then seiteki mainoriti[4], then the fully native term, seiteki shōsūsha[5]. The owner somewhat understood the latter, but asked me to be more specific. I explained that I was referring to people who love people of the same-sex or whose gender identity does not match their biological identity. The owner then exclaimed: ‘Oh! Is this about homos[6]?’ From a cross-cultural perspective, Japan is often portrayed as a comparatively tolerant country due to the scarcity of LGBT-related hate crime and active persecution (Vincent, Kazama and Kawaguchi 1997, 170). However, discrimination exists at a systematic and institutional level, as Japan does not have an anti-discrimination law, same-sex partnerships are only recognised to a limited extent in certain cities, and workplace discrimination, bullying, and suicide rates continue to be a problem for the queer population. The current consensus seems to be that queer culture is tolerated, so long as it stays segregated and does not disturb the majority (Equaldex n.d.; Hidaka et al. 2008; Taniguchi 2006; Vincent, Kazama and Kawaguchi 1997).

In addition to their fight for human rights within a national context, the queer community is facing an additional internal struggle regarding their direction, approach, and even terminology. ‘Global queering’ and the formation of the ‘global gay’ have become a topic of interest surrounding the formation of queer identities and sexualities in Asia as globalisation has paved the way for new cultural flows between queer communities around the globe (Altman 1996; Jackson 2009). Though Western influence over the understanding of Japanese sexuality and relationships has been present since the late nineteenth century, the ‘global gay’ and its identity politics is said to have become particularly noticeable in Japan since the 1990s. Until then, the Japanese queer community had evolved differently than the Western model, intertwined but facing different obstacles, developing separate terminologies and performances (McLelland 2000, 2005). A paradigm shift occurred in 2010, which saw an almost full switch from local terminology and discourse to Anglicised terms and symbolism that gained national attention, in what is informally referred to as the LGBT Boom (Horie 2015).

This chapter offers a short overview of queer discourse in Japan, the state and terminology of the LGBT Boom, and its position within national and global queer discourse.

Queer History in Japan

Though cases of same-sex love, cross-dressing, and individuals living as genders different from what was assigned at birth are documented throughout premodern Japanese history, they do not match current understandings of gay or transgender identities, as they were consolidated within strict social roles, linked to lifestyle or religious occupations, not placed within a heterosexual dichotomy, and referred almost exclusively to males (Horie 2015, 199–200; Itani 2011, 284–285; McLelland 2011).

In the late nineteenth century, Japan adopted many Western values in the handling of relationships, institutions, familial relations, and social values, which extended to public stances on homosexuality. Though the Japanese sodomy law was lifted after only twelve years, the taboo lived on in the public consciousness, and transsexualism was pathologised (McLelland 2000, 22–25; Itani 2011, 285–286; Mitsuhashi 2003, 103). Removed from the public sphere, Japanese queer culture steadily developed throughout the twentieth century in bars, underground magazines, and an entertainment sector mostly consisting of gay men and crossdressers (Yonezawa 2003; McLelland 2005).

Attempts to politicise their discourse and form alternate communities are noticeable starting in the 1970s, within grassroots gatherings, gay magazines, and the occasional breach into politics or mainstream entertainment (McLelland et al. 2007; Sawabe 2008; Sugiura 2006). However, it wasn’t until the 1990s that a wider political LGBT discourse formed.

In what is informally known as the ‘Gay Boom’, the 1990s saw a considerable increase in media portrayals of queer characters, as well as manifestos and autobiographies from members of the LGBT community. Simultaneously, local and international organisations were involved in combating HIV/AIDS, and advocacy groups took the first steps to legally combat LGBT discrimination and advocate for a national queer discourse, leading to the idea of identitarian sexuality taking form in Japan.

Most notably, transgender advocates achieved a series of successes starting in the mid-1990s: Gender Identity Disorder (GID) was translated into Japanese in 1996, which led to the legalisation of sex reassignment surgery (Itani 2011, 282). In 2003, trans woman Kamiwaka Aya became the first elected Japanese LGBT politician, and worked to introduce a law which allowed trans citizens to change their gender in the Official Family Register. While severely limited, this set a precedent as the first legal recognition of queer people in Japan, (Kamikawa 2007; Taniguchi 2013). Where the term ‘sexual minorities’ previously represented gay or crossdressing men, the medical and political backing of the transgender rights movement had managed to turn the concept of sexual minorities into a placeholder for people suffering from GID in the public eye (Horie 2015, 196). At the same time, lesbian, gay, intersex, asexual, and other queer groups continued solidifying throughout the 2000s, both locally and online (Dale 2012; Fushimi 2003, 197–224; Hirono 1998; ‘The History of Asexuality in Japan’ n.d.). The politics of coming out gradually entered the movement’s consciousness, though it has yet to be readily embraced by the general population.

The term ‘LGBT’ rapidly spread in vernacular activism in the 2010s (Horie 2015, 167), and the election of two more gay public officials in 2011 seemed to solidify the LGBT movement’s political direction. Pride celebrations spread across the country, and over 70,000 people attended the Tokyo parade[7]. The international wave of civil partnership laws prompted discussion among the national policy-makers, and Shibuya ward in Tokyo was the first to make them official in 2015[8], followed by another five districts and cities the following year. The 2016–2017 election season brought another four LGBT politicians into city councils and even the national assembly. By 2018, it seemed that Japan had managed to establish a solid queer presence that breached into mainstream politics.

Despite the LGBT Boom’s unprecedented success, queer people themselves are not always in line with its discourse. Within the community, a counter-discourse is forming around members who are against LGBT Boom goals and values such as same-sex marriage, coming out, focus on visibility and assimilation, and the terminology of the discourse itself. The following section is concerned with the terminology and symbolism that are currently employed by the Japanese queer community, and how they entered the vernacular.

Queer Terminology and Symbolism in Japan

Loanwords in the queer community are not a recent phenomenon. The first mention of homosexuality in modern Japanese society relied on the term uruningu[9], brought in by Mori Ōgai from Germany (McLelland 2000, 22), and foreign terms such as pederasuto/pede[10], lezubosu[11], safisuto[12], daiku[13], and burū bōi [14] were used sporadically throughout the decades (McLelland et al. 2007). However, these terms were used exclusively within queer spaces, especially in gay bars and cruising sites. Most of the currently used LGBT terms were initially adopted in the post-war period, but their meanings and extent have shifted considerably; it was during the Gay Boom that queer terminology took a more definitive Anglocentric approach, and previous terminology (borrowed and native alike) started to be considered archaic, old-fashioned, or derogatory. The change was amplified by the efforts of queer activist groups in changing and adopting Japanese queer terminology in a direction that separates it from allusions to femininity, prostitution, and medicalised jargon (Lunsing 2005, 82–83). To keep up with the shifting terminology, members of the community employ various tactics.

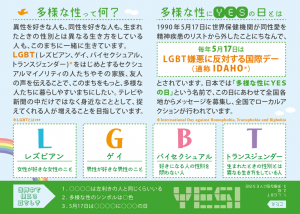

One way in which activists confront the linguistic barrier is through the constant explanation of terms. Many queer websites and pamphlets feature explanations of the terms in a visible area; the following is a typical example, as seen in a pamphlet advertising IDAHO (the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia):

Figure 1. The back of a pamphlet advertising IDAHO, called ‘say YES to sexual diversity day’ in Japan. From ‘5 gatsu 17 nichi ha「tayou na sei ni YES no hi」!’ by Yappa AiDAHO , 2018. Copyright 2018 by Yappa AiDAHO idaho.net. Reproduced with permission.

Explanations start by singling out the letters of the LGBT acronym in the Roman alphabet, then rendering it phonetically, followed by a short explanation of the meaning either mechanically (women who love women, men who love men, people whose lifestyle does not match the one assigned at birth, etc.) or using native terms. Often, they add an explanation as to why the native or commonly used terms are considered inappropriate.

Activists are currently in favour of LGBT terminology, despite the linguistic barrier. This is mainly due to the history of these terms and their development within – and especially outside – the community. The following is a breakdown of how L,G,B, and T entered the Japanese vernacular, and what they are meant to replace.

L

I knew the words ‘homo‘ and ‘rezu‘[16], but they were just perverted words that I learned in primary school. (Ōtsuji 2005, 54)

As the Japanese language does not feature the letter L, lesbian has entered the language as rezubian. However, advocates have chosen to keep the letter L in the term LGBT.

The word rezubian was first recorded in Japan in 1963, referring to a female bartender dressed as a man (Sugiura 2006, 130). Later, its abbreviation, rezu, became associated with male-oriented pornography, though it was one of the many terms employed by grassroots lesbian movements starting in the 1970s. Rezubian as a self-named identity took over during the 1990s (Horie 2015). One major problem that it faced was the negative connotation that the word rezubian (especially rezu) had for being used by male-targeted lesbian pornography – not only did lesbians have to inform others of their existence, but they had to erase the previous negative usage of the word (Kakefuda 1992). Rezubian was shortened to bian by the Lesbian community around the mid-1990s, as they wanted to refer to themselves using a word that discarded its mainstream connotation. Unlike rezu, which continues to be used in pornography or as a derogatory term, bian has not successfully entered the mainstream language, and is mostly used as a lavender term within the community.

G

‘Tsuyoshi, are you homo?’

‘Yeah, but since homo isn’t a good word, call me gei[17]‘. (Ryoji and Sunagawa 2007, 51–52)

Homo entered the Japanese language in the 1920s, and has maintained a fairly constant derogatory connotation since, though its presence continues to be strong in popular media. The word gei first entered the language in the postwar period and was used to refer to gei boi[18], male sex workers and crossdressers working in designated bars. It wasn’t until the Gay Boom that gei became associated with male-identified homosexuals, but it has since become the preferred term to refer to men who love men.

The native term dōseiaisha[19] is still used to refer to male homosexuals, although some find it too medical-sounding or criticise its tendency to refer to gay men and women alike (Ishikawa 2011).

B

As is unfortunately the case with queer communities around the world, bisexual erasure is quite common in the Japanese queer community, as bisexuals are caught in the divide between heterosexuals and homosexuals and become either assimilated or shunned (Matsunaga 1998). Given the divide between married life and sexual enjoyment, people who have affairs with the same-sex, but marry a member of the opposite sex do not take on the bisexual identity, but either identify as homosexual or ‘grow out of it’ (McLelland 2000). Though bisexuality is always included when explaining the term LGBT, for the most part they are absent from general discussions and movements. The native term ryōseiaisha[20](or zenseiaisha[21] for pansexuals) exists, but it is simply not used as much as baisekushuaru[22]or bai [23](Hirono 1998).

T

‘Oi, Okama[24]!’

[…] ‘Uhm, “Okama” is slightly different. “Okama” was originally a feminine man, so I guess I would be an “onabe”, right? Oh, but “onabe” is pretty tied to the entertainment industry, much like “new half”, so once again it’s not really me. By the way, if you call me a lesbian then that’s not really right, either (Sugiyama 2007, 207).

Before the 1990s, transgender (and crossdressing) individuals were referred to using the terms okama, gei boi, onee[25], or nyū hāfu[26]. The lesbian community used the word onabe[27] to refer to butch lesbians initially, though that term evolved to describe FtMs (female to male) around the mid-1990s (Sugiura 2006).

The word toransujendā[28] is said to have been introduced in 1994, with the narrow sense of a full-time biologically male crossdresser who did not wish to undergo sex reassignment surgery (Itani 2011, 288). Transgender individuals who decided to transition referred to themselves as toransekushuaru[29]. Transgender individuals who did not transition at all, or lived a double life, were derogatorily referred to as toransuvesutaito[30], often abbreviated as TV.

Toransujendā became the preferred term within the community in the 2000s, alongside the English acronyms of FtM and MtF[31]. This change in approach mirrored the Western debate, which underwent a similar transformation of preferred terms. The Japanese trans community did not, however, extend Toransujendā to cover the entire trans umbrella to include non-binary identities.

Despite the derogatory connotations, some transgender individuals who willingly refer to themselves as okama, onabe, or nyū hāfu, and they are still the most commonly used words in Japanese society. However, advocates posit that these terms are more often used as slurs or are restricted to the entertainment industry. Okama, in particular, being a well-known term, is used as a slur against gay men, intersex individuals, and other queer groups alike (Fushimi 2003).

The most problematic aspect regarding native terms for trans individuals is that there is no word used to describe a transgender person. Even though GID was replaced with gender dysphoria in the DSM-V, the term GID is widely used, often as a placeholder for gender-non-conforming individuals. When explaining the T in LGBT, advocates use descriptions such as ‘a person suffering from GID’, ‘a person whose sex does not match their gender’, etc., but it is not uncommon to refer to the individual simply as ‘GID’, even within the community. Due to the focus on GID as a pillar for the transgender movement’s legitimacy, TG/TV people are still often separated from TS depending on their desire to undergo sex reassignment surgery (or not): non-cisgender individuals who do not desire medical treatment are not seen as ‘real’ representatives of their community.

Symbols

The Anglocentric influence is not limited to word usage: it also affects symbols. In 2017, all the queer parades in the country relied on international symbolism and terms: The Tokyo Rainbow Parade, the Nagoya Rainbow Parade, the Kyushu Rainbow Pride, the Sapporo Rainbow March, the Kumamoto Pride, the Kansai Rainbow Festa, the Aomori Pride, the Okinawa Pink Dot[32], and many non-profit organisations use the words Pride, Diversity, or Rainbow in their names.

There is a great discrepancy between the use of the rainbow as a queer symbol and the rainbow in mainstream media. Despite the heavy use of rainbows within the queer community, the rainbow is not seen as a queer symbol in mainstream discourse: colourful rainbows are often employed as decorations in Japan. For example, while Nagoya Rainbow Week 2016 used the rainbow to paint itself as a queer event, the Aichi Trienalle 2016 edition called ‘Rainbow Caravan’[33] took place simultaneously in the same city centre, with no queer context behind it. It was thus easy for passersby to consider the Nagoya Rainbow Week an art event that was related to the Trienalle, rather than a stand-alone queer event.

Similarly, words such as puraido[34] or daibāshitī[35] can be a barrier: one needs to first understand the word pride/diversity in English, then to know its political connotation within the international queer community. It is difficult to figure out exactly when Pride and rainbows made their way into Japan due to the scarce literature on the matter, but their popularity has escalated since the 2010s (Welker 2010).

Anglicisation or Hybridity?

In the 1990s, the international HIV/AIDS movement helped establish a precedent in countries where homosexuality had been previously ignored or even prosecuted. But in doing so it has become a tool susceptible to globalisation and the promotion of an international gay/lesbian agenda based on a Western/US model (Altman 1996). This trend was accused of dividing international gay formations from local homosexualities, causing an identity crisis among the native population who felt pressured to replace their local identities with Western LGBT ones. Critics of global queering encouraged caution and the need to include non-Eurocentric perspectives into the definition of sexuality. A counter-discourse to global queering as a hegemonic force pointed out that it assumes a strict dichotomy between East/West, dominator/dominated, etc., and that it overstates the influence of the West over Asian discourse. As maintained by this view, rather than imposed, Western categories are assimilated and redefined according to local values in a process of queer hybridity (Boellstorff and Leap 2004; Martin et al. 2008).

Westerners tend to perceive English terms in Asian cultures as proof of Westernisation, but in doing so they disregard the changes that these terms have undergone locally. Though globalisation is often associated with homogenisation/Anglicisation, developments in local contexts contribute to a multidimensional understanding of values on a transnational, rather than universal, scale. Understanding contemporary queer movements in Asia as mere imitations greatly oversimplifies the matter. While it is true that English terms have become part of the local queer discourse, they do not always fully mirror their Western equivalents, and as we can see, they were not adopted overnight, but rather as a result of ongoing negotiations and discourse development (Jackson 2009; Wilson 2006).

Shimizu Akiko (2007) states that we cannot really talk about global queering in the case of Japan, since there were no instances of native understandings of queer identities outside a Western frame to begin with. The borrowing and redefinition of English terminology according to local standards can be seen in Japan over the decades, where locals used their own subjective experience to define and redefine their sexual identity and its name. This exchange has been fueled first by international exchanges and transnational organisations, but the result was always a hybrid between the Western model and local subjectivities.

However, it is important to note that this debate was mostly carried out before the 2010 LGBT Boom, which emulates Western terminology and tactics to a wider extent.

While its strategic use has proved successful in national politics, media, and recognition, it is important to evaluate how well it resonates with Japan’s queer population. Otherwise, the LGBT Boom risks alienating the members it claims to represent, while also failing to reach out to a wider Japanese audience, since it relies on terms and premises that the locals do not necessarily recognise. Additionally, the focus on same-sex partnership and coming out has also been adopted to imitate the Western ideals of the queer agenda, but the question must be raised deeper within the Japanese context.

Hybrid or not, the Anglocentric terminology is not just an issue of linguistic historicity, but has become a linguistic barrier within the community. According to a survey performed by the Japan LGBT Research Institute (2016), only 49.8% of the respondents who identified as non-cisgender and non-hetero knew what the LGBT acronym meant, and those unfamiliar with Western LGBT culture and terminology are unlikely to recognise the terms or symbols when they see them. Current queer terminology in Japan has become diglossic, as native terms are considered pathological, derogatory, or old-fashioned (even though they see use within the community), whereas the English terms are seen as empowering due to their international symbolism.

Conclusion

I raise these issues not to entirely dismiss the LGBT Boom discourse, but to present a more comprehensive picture of the current state of the community and its discourse. As Shimizu (2005) points out, reactionary radical resistance to the Anglocentric terms is not necessarily promoting local movements, so much as stagnating political advancement in favour of polemics outside the scope of the actual movement. It is true that the uncritical adoption of international terminology carries the risk of normativisation, rendering subjectivities invisible. However, one must be careful when dismissing the model employed by Japanese activists as strictly Western: it can be seen as merely a strategic tool employed by activists to stir up debate, rather than to overwrite native identities (Suganuma 2007, 495–496).

The separation between political queer discourse and local behaviour has long existed (Horie 2015, 65; Shimizu 2007, 508–510), so perhaps this Western discourse/local acts divide is just continuing that trend, trying to gain the strategic advantage in mainstream discourse whilst allowing native queer culture to develop. It was there during the Gay Boom, it is here during the LGBT Boom. What is necessary is more awareness regarding the gap between identity politics discourse and those it represents.

The current confusion doesn’t have to be permanent, and attempts to combine approaches are already underway. Since the 1990s, a steady stream of autobiographies have been released, in which activists and public figures merge identity politics with their subjective experience, all while explaining queer terminology and how they feel about it (Fushimi 1991; Kakefuda 1992; Kamikawa 2007; Ōtsuji 2005; Sugiyama 2011). Though it is still a work in progress, activists are working on reaching out to a wider audience using introductory books, mangas, and videos on queer issues (Harima et al. 2013; Hidaka 2014; Ishida et al. 2010; Ishikawa 2011). Moreover, institutional efforts seek to raise LGBT awareness in schools and workplaces, offering access to information and allowing new venues for discussion. Hopefully, the confusion and polemics are merely a phase that will be remembered as a footnote in Japanese queer history, rather than a definite divide.

Notes

[1] When transcribing Japanese, macrons (¯) are used to show when a vowel should be prolonged in pronunciation. Japanese names are written in Japanese order, with the surname first. The Japanese language uses three types of character sets: Kanji (Chinese characters) and two syllabaries; loanwords are usually transcribed phonetically, rather than translated, and some loanwords are abbreviated or acquire alternate meanings, a process referred to as wasei eigo (Japanised English). Given the phonetic nature of these words, speakers unfamiliar to the word would not understand its meaning intuitively.

[2] I use the term ‘queer’ to refer collectively to all sexual and gender minorities. Additionally, though the queer community can be referred to as LGBTQ, LGBTQIA+, etc., the term LGBT will be used throughout this chapter, given its current use as the default term in Japanese discourse. The term ‘sexual minority’ has come under criticism for grouping sexual and gender minorities under the same umbrella, but its uses and political intricacies are beyond the scope of this article.

[3] Phonetic rendition of sexual minority.

[4] Native term for sexual (and gender), phonetic rendition of minority.

[5] Fully native term for sexual minority.

[6] The Japanese term homo and the English term homo have the same etymological formation, history, and negative connotation. The Japanese queer community considers it a slur.

[7] Following (or perhaps starting) the shift in vernacular, the Tokyo Gay and Lesbian Parade changed its name to Tokyo Rainbow Pride.

[8] It should be noted that the legal recognition of these civil partnerships is virtually non-existent, though they are often referred to as ‘same-sex partnerships’: they are not recognized nationally, and only offer a limited amount of recognition and rights to the individuals who register for it.

[9] Phonetic rendition of urning, a German term used to describe same-sex lovers in early sexology.

[10] Phonetic rendition of pederast.

[11] Phonetic rendition of lesbos.

[12] Phonetic rendition of Sappho.

[13] Phonetic rendition of dyke.

[14] Blue boy, a term that became popular in the 1950s and 1960s after a Paris play.

[15] https://idaho0517.jimdo.com/

[16] Rezu is the Japanese equivalent of ‘lezzie’: an abbreviation of rezubian/lesbian that is casually used in a derogatory manner.

[17] Phonetic rendition of gay.

[18] Phonetic rendition of gay boy.

[19] Lit. ‘same-sex lover’.

[20] Lit. ‘lover of both sexes’.

[21] Lit. ‘lover of all sexes’.

[22] Phonetic rendition of bisexual.

[23] Phonetic rendition of bi.

[24] Lit. an archaic term for buttocks that has been in use since the Edo period to describe men who have sex with men and crossdressers.

[25] Big sister.

[26] From New Half, a term that was popularised in the 1970s by crossdressing entertainers as someone who is half of both genders.

[27] This is a play upon words. Kama has switched meanings from ‘buttocks’ to a type of pot in modern Japan. Nabe is yet another type of Japanese pot. Therefore, onabe refers to them being a different kind of okama.

[28] Phonetic rendition of transgender.

[29] Phonetic rendition of transsexual.

[30] Phonetic rendition of transvestite.

[31] Interestingly, rendition of transvestite.

[31] Interestingly, non-binary individuals (who identify as X-gender) use the same naming system, calling themselves MtX or FtX.

[32] Named after the Pink Dot festival in Singapore.

[33] One of the largest art festivals in Japan, held every three years in the city of Nagoya, Aichi prefecture.

[34] Phonetic rendition of pride.

[35] Phonetic rendition of diversity.

References

Altman, Dennis. 1996. “On Global Queering.” Australian Humanities Review 2: 1–9.

Boellstorff, Tom, and William L. Leap. 2004. Speaking in Queer Tongues: Globalization and Gay Language. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Dale, S.P.F. 2012. “An Introduction to X-Jendā: Examining a New Identity in Japan.” Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 31: n.p. http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue31/dale.htm#t19.

Equaldex. n.d. “LGBT Rights in Japan.” Equaldex. Accessed November 27, 2016. http://www.equaldex.com/region/japan.

Fushimi, Noriaki. 1991. Puraibēto Gei Raifu. Tokyo, Japan: Gakuyō Shobō.

Fushimi, Noriaki. 2003. Hentai (kuia) Nyuumon. Tokyo, Japan: Chikuma.

Harima, Katsuki, Toshiyuki Ōshima, Aki Nomiya, Masae Torai, and Aya Kamikawa. 2013. Sei Dōitsusei Shōgai to Koseki : Seibetsu Henkō to Tokureihō O Kangaeru. Tokyo, Japan: Ryokufū Shuppan.

Hidaka, Yasuharu. 2014. Anata Ga Anatarashiku Ikiru Tame Ni – Seiteki Mainoriti to Jinken. Tokyo, Japan: Tōei. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G9DhghaAxlo.

Hidaka, Yasuharu, Don Operario, Mie Takenaka, Sachiko Omori, Seiichi Ichikawa, and Takuma Shirasaka. 2008. “Attempted Suicide and Associated Risk Factors among Youth in Urban Japan.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 43 (9): 752–57.

Hirono, Maki. 1998. “Baisekushuaru Ni Tsuite No Q&A [Bisexual Q&A].” In Anata, Okama, Kirai?. Osaka, Japan: Project P. http://barairo.net/works/TEXT/bifaq.html#Anchor-Q8.

Ishida, Ira, Sonin, Fumino Sugiyama, Kenichirou Mogi, Frankie Lily, Pico, Sachiko Takeuchi, Katsuki Harima, and Toshiaki Hirata. 2010. NHK「hāto Wo tsunagou」LGBT BOOK. Tokyo, Japan: Ōta shuppan.

Ishikawa, Taiga. 2011. Gei No Boku Kara Tsutaetai Suki No Wakaru Hon – Minna Gashinranai LGBT. Tokyo, Japan: Tarō Jirōsha Editasu.

Itani, Satoko. 2011. “Sick but Legitimate? Gender Identity Disorder and a New Gender Identity Category in Japan.” In Sociology of Diagnosis, edited by PJ McGann and David J. Hutson, 281 – 306. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group.

Jackson, Peter A. 2009. “Global Queering and Global Queer Theory: Thai [trans] Genders and [homo] Sexualities in World History.”Autrepart 1: 15–30.

Japan LGBT Research Institute. 2016. “Hakuhōdō DY gurūpu no kabushikigaisha LGBT sōgōkenkyūsho, 6 tsuki 1-nichi kara no sābisu kaishi ni atari LGBT o hajime to suru sekusharumainoriti no ishiki chōsa o jisshi”. Tokyo, Japan: Kawadeshobōshinsha.

Kamikawa, Aya. 2007. Kaete Yuku Yūki : “Sei Dōitsusei Shōgai” No Watakushi Kara . Tokyo, Japan: Iwanami.

Lunsing, Wim. 2005. “The Politics of Okama and Onabe: Uses and Abuses of Terminology Regarding Homosexuality and Transgender.” In Genders, Transgenders, and Sexualities in Japan, 81–95. New York, NY: Routledge.

Martin, Fran, Peter A. Jackson, Mark McLelland, and Audrey Yue, eds. 2008. AsiaPacifiQueer: Rethinking Genders and Sexualities. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Matsunaga, Kazumi. 1998. “A Bisexual Life.” In Queer Japan: Personal Stories of Japanese Lesbians, Gays, Transsexuals, and Bisexuals, edited by Barbara Summerhawk, Cheiron McMahill, and Darren McDonald, 37–45. Online publishers: New Victoria Publishers.

McLelland, Mark J. 2011. “Japan’s Queer Cultures.” In The Routledge Handbook of Japanese Culture and Society, edited by Victoria Bestor and Theodore Bestor, 140–49. New York, NY: Routledge.

McLelland, Mark J. 2000. Male Homosexuality in Modern Japan: Cultural Myths and Social Realities. Richmond, UK: Curzon Press.

McLelland, Mark J. 2005. Queer Japan from the Pacific War to the Internet Age. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Mitsuhashi, Junko. 2003. “Nihon Toransujenda Ryakushi (sono 1) – Kodai Kara Kindai Made.” In Toransujendarizumu Sengen: Seibetsu No Jikotteiken to Tayō Na Sei No Koutei, edited by Yonezawa, 104–18. Tokyo, Japan: Shakaihihyōsha.

McLelland, Mark, Katsuhiko Suganuma, and James Welker. 2007. Queer Voices from Japan: First Person Narratives from Japan’s Sexual Minorities. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Ryoji, Sunagawa and Hideki Sunagawa. 2007. Coming out Letters. Tokyo, Japan: Tarō Jirōsha.

Sawabe, Hitomi. 2008. “The Symbolic Tree of Lesbianism in Japan: An Overview of Lesbian Activist History and Literary Works.” In Sparkling Rain: And Other Fiction from Japan of Women Who Love Women, edited by Barbara Summerhawk and Kimberly Hughes, translated by Kimberly Hughes, 2–16. Chicago, IL: New Victoria Publishers.

Shimizu, Akiko. 2005. “The Catch in Indigenousness, Or What Is Wrong with ‘Asian Queers’.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6 (2): 301–3.

Shimizu, Akiko. 2007. “Scandalous Equivocation: A Note on the Politics of Queer Self‐naming.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 8 (4): 503–16.

Suganuma, Katsuhiko. 2007. “Associative Identity Politics: Unmasking the Multi-Layered Formation of Queer Male Selves in 1990s Japan.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 8 (4): 485–502.

Sugiura, Ikuko. 2006. “Lesbian Discourses in Mainstream Magazines of Post-War Japan: Is Onabe Distinct from Rezubian?” Journal of Lesbian Studies 10 (3-4): 127–44.

Sugiyama, Fumino. 2009. Double Happiness. Tokyo, Japan: Kōdansha.

Ōtsuji, Kanako. 2005. Kamingu Auto : Jibunrashisa O Mitsukeru Tabi. Tokyo, Japan: Kōdansha.

Horie, Yuri. 2015. Lesbian Identities. Tokyo, Japan: Rakuhoku.

“Nihon No Asekushuaru No Kako [The History of Asexuality in Japan].” n.d. Asexual.jp. Accessed November 25, 2016. http://www.asexual.jp/history_japan.php.

Taniguchi, Hiroyuki. 2006. “The Legal Situation Facing Sexual Minorities in Japan.” Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context 12: n.p. http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue12/taniguchi.html#t1.

Taniguchi, Hiroyuki. 2013. “Japan’s 2003 Gender Identity Disorder Act: The Sex Reassignment Surgery, No Marriage, and No Child Requirements as Perpetuations of Gender Norms in Japan.” Asian – Pacific Law & Policy Journal 14 (2): 108–117.

Vincent, Keith, Kazuya Kawaguchi, and Takashi Kazama. 1997. Gay Studies. Tokyo, Japan: Seidōsha.

Welker, James. 2010. “Telling Her Story: Narrating a Japanese Lesbian Community.” Journal of Lesbian Studies 14 (4): 359–80.

Wilson, Ara. 2006. “Intersections: Queering Asian.” Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context 14 (November): n.p. http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue14/wilson.html#t32.

Yappa AiDAHO idaho.net. 2018. “Download Pamphlet.” 5 Gatsu 17 Nichi Ha「tayou Na Sei Ni YES No Hi」. 2018. https://idaho0517.jimdo.com.

Yonezawa, Izumi. 2003. Toransujendarizumu. Tokyo, Japan: Shakaihihyōsha.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Russian Democrats’ Stance on the LGBT Community: An Attitudinal Shift

- Opinion – What a Stronger Japanese Military Posture Means for Okinawa

- Opinion – Shinzō Abe and Russo-Japanese Relations

- Donors’ LGBT Support in Tajikistan: Promoting Diversity or Provoking Violence?

- The Transnational in China’s Foreign Policy: The Case of Sino-Japanese Relations

- Evolution of Sino-Japanese Relations: Implications for Northeast Asia and Beyond