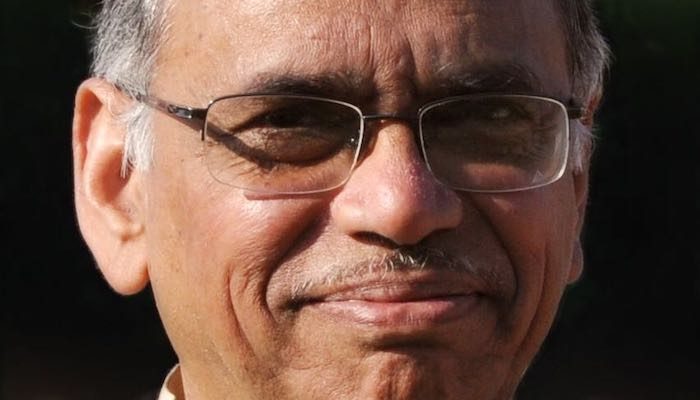

Nayan Chanda is the founder and former editor-in-chief of YaleGlobal Online which started in 2002. Before his time at Yale, he spent nearly thirty years with the Far Eastern Economic Review, a Hong Kong-based publication, as its editor and Indochina correspondent. He was also a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington and the editor of the Asian Wall Street Journal Weekly. He has authored numerous books including Bound Together: How Traders, Preachers, Adventurers, and Warriors Shaped Globalization and Brother Enemy: The War After the War. He is the recipient of the 2005 Shorenstein Award. He is currently associate professor of International Relations at Ashoka University.

How has the way you understand the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

It is an important question. The world is increasingly more difficult to understand as everything is moving faster, the scale is increasingly larger and human reactions are faster, deeper and louder. In one way the world has shrunk – both in terms of distance and communications, in terms of changing matter and transmitting bytes. But in another way the world has become more fragmented and distances between people have grown. These changes are evident to anyone who has lived through the seventies and eighties. Technology has changed and along with it some parts of the world have also changed rapidly and dramatically. However, other parts have changed very slowly. The disparity has created a growing dissonance – between technology and society. There has always been a need to look at the world as ‘matters in motion’. But now with the growing interconnectedness one has to look at the dynamic world in a multi-dimensional way.

At the recent G20 summit, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce announced that the US would have to remove existing tariffs on China before a deal could be made. Do you believe a deal is likely in the near future?

As many predicted, the US-China trade dispute may not be resolved soon. Postponement of trade negotiation, imposition of new tariffs on Chinese exports, cancellation of promised Chinese purchase of American soybean and the US calling China a “currency manipulator” all suggest a lasting solution to the dispute may have to wait till the 2020 presidential election. As both countries are hurting, there is an incentive for a compromise but given the deep differences that remain over systemic issues, a deal that might be reached now would only cover limited areas and prove short-lived. It’s possible that the Chinese would place some orders for American soybeans and the US will allow some limited sale of technology components to China’s Huawei corporation. The underlying differences in China’s trade practices and competition over technology are at the base of the struggle for supremacy of the two superpowers.

Are there parallels between the nature of US-China trade today and the trade relationship that the US and Japan shared in the 1980s? If so, what is the significance of this?

There is indeed a lot of similarity between the US-Japan trade dispute of the 1980s and the Sino- American trade clash today. Like the Chinese Japan manipulated its currency, raised tariff and non-tariff barriers, subsidized manufacturers and even tried to pilfer technology. Those conflicts were resolved with the US imposing tariffs and restricting imports of Japanese automobiles and TVs. The US-Japan trade competition occurred against the backdrop of a weak China and a troubled Soviet Union. The value of the US-Japan strategic alliance increased with the growing power of China. Globalization also made the Japanese economy and technology, especially the auto industry more interdependent. While Trump’s tariff war against Japanese steel and automobiles has caused some tension the nature of their trade dispute is very different.

What are the wider economic and political repercussions of this trade war? What could it mean for other rising Asian powers such as India in terms of US-India relations?

In the near term the US-China trade war has benefited some Asian countries as higher US tariffs has forced some companies to move their production facilities out of China to countries like Vietnam, Taiwan, South Korea and Mexico. Such transfers, of course, only reinforce a trend that started with demographic changes in China. Not only western manufacturers but Chinese companies too could be moving their operations to low wage countries. The US-China trade war may have very limited direct economic impact on India as it is not an attractive location for a variety of reasons – labor laws, skills and infrastructure. Growing trade tension between China and Washington though could increase the value of US strategic partnership with India.

Which economic or geopolitical aspects of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) do you find most encouraging or concerning?

China’s Belt and Road initiative could be very beneficial to the region as it promises to provide funding for building road, rail and power networks sorely needed by the region. The Asian Development Bank estimated that the region needs some $800 billion a year to meet the region’s infrastructure needs. Some estimates put China as already having spent about $200 billion on such infrastructure. Apart from using China’s unused resources and employing its labour, the BRI allows China to gain geopolitical supremacy in the region. For example, the case of the Sri Lankan deep-water port shows that massive loans extended to the BRI partners can also catch them in a debt trap. Unable to service the Chinese loan Sri Lanka was obliged to hand over the port of Hambantota to China on a very long-term lease. China’s so-called ‘digital Silk Road’ also opens the participating nations communications infrastructure and 5G network to Chinese state-controlled companies. As it can be seen in Pakistan and Cambodia the BRI project can also be harnessed to China’s strategic interests

To what extent do you think we are currently witnessing a backlash against globalization? Can any parallels be drawn from the history of globalization?

The rise of populism in the US, UK and parts of Europe and South America clearly show a backlash against globalization. Corporate profit and technology driven globalization has created an increasingly fast and interconnected world where masses of people, especially unskilled workers have been left behind expanding the gap between the top one percent of the population and the rest. Protectionism has risen to slow down trade and interconnectedness. Global climate change, economic failure and warfare have driven millions of refugees and asylum-seekers to developed countries creating anti-immigrant and anti-globalization responses. The history of globalization is replete with examples of protectionism, anti-religious, and anti-immigrant backlash in different periods. Europeans have fought long wars to defend their faiths and protect their economy. Global trade has periodically come to a halt because of hostility among nations. But given the vast size of today’s interconnected global markets any trade slowdown would have a much wider and longer-term impact on all nations.

After your experience covering the Third Indochina War as a journalist you wrote Brother Enemy: The War After the War in 1986. What was the most striking aspect of that conflict and your experience covering it?

Covering the wars in Indochina was a traumatic experience the effect of which still lingers. Witnessing so much death, destruction and suffering has not inured me. It has made me ever more sensitive to suffering. Witnessing examples of great heroism and generosity amidst violence has given me new respect for life and also a new respect for human resilience, selflessness, kindness and ingenuity. The experience of covering the Indochina conflict, getting to know the actors – from heads of government to foot soldiers – makes you feel awed by the power of nationalism, the hold of ideology and propaganda on people. The Indochina wars which saw many reversals of alliances showed the truth of Lord Palmerston’s observation that nations have no permanent friends or allies, they only have permanent interests.

What is the most important advice you could give to young scholars or journalists of International Relations?

Everybody will find their own approach to studying international relations or practicing journalism. From my vantage point I think reading history – both world history and history of the country or people you focus on – is extremely helpful. I have tried to practice the advice that I am suggesting – understand where one is coming from, be sceptical, and analyse reasons behind statements. Avoid monocausal analysis and read as widely as possible seeking connections between events and phenomena.