Japan and the EU are constructed as partners sharing common values such as democracy, human rights and the rule of law. Furthermore, the EU praises Japan as being ‘one of the EU’s closest and most like-minded partners’ (European External Action Service). Departing from the notion of Normative Power Europe, this should be reflected in their respective policies towards China, which has been labelled as a ‘systemic rival’ by the European Commission (European Commission and HR/VP). As can be seen in the South China Sea territorial disputes, a more assertive China can form a challenge against global order and rule of law and could thereby be grounds for intensified cooperation between the EU and Japan. In this paper, I will answer the question of how the rise of China influenced EU-Japanese relations. To answer this question, I will first do a literature review on EU foreign policy and on EU-Japan relations. Secondly, I will discuss the implications of the rise of China on EU foreign policy. Thirdly, I will look at how Japan responded to this in order to see if we can find any similarities between their approaches. Fourthly, I will assess the EU’s foreign policy towards Japan in light of the previously discussed developments, after which I will analyse statements regarding the South China Sea from both countries. Lastly, I will conclude by placing my findings in wider debates on the role of the EU as a global actor. In doing so, this paper aims to contribute to the understanding of EU foreign policy in East Asia, its challenges and the advantages and disadvantages of the current approach.

Literature Review

Within the context of EU foreign policy studies, the notion of Normative Power Europe remains very influential. Normative Power Europe can, at its most basic level, be defined as the idea that the EU is not only created on values such as respect for human rights and democracy but that these norms are also integrated in its foreign policy (Neuman and Stanivuković 3). Indeed, we can find an emphasis on ‘(European) values’ in the EU global strategy. It is also present in the discourse on EU-Japan relations, where the EU-Japan Strategic Partnership is described as being based on ‘longstanding cooperation, shared values and principles such as democracy, the rule of law, human rights, good governance, multilateralism and open market economies’ (Council of the European Union). Not only do the two countries share values, but Japan is also ‘one of the EU’s closest and most like-minded partners’ (European External Action Service). This designation of Japan as one of the EU’s closest partners can, however, be questioned. Tsuruoka identifies what he refers to as an Expectations Deficit. This notion departs from the Capabilities Expectations Gap coined by Hill, a concept which describes the mismatch between expectations of the EU and its capabilities to act, where the latter outweigh the former. Tsuruoka criticises this notion for its one-sidedness: it does not allow for the possibility of the capabilities to actually outweigh the expectations, a possibility which is exemplified by the EU-Japan relationship (111). This notion is therefore firmly grounded in debates on the role of the EU as a global actor. Rhinard and Sjöstedt reflected on the notion of actorness more generally, distinguishing both ‘actor capability’ and ‘actor behaviour’ (6). Here three different categories for capacity can be distinguished. First, there is the EU’s internal coherence, which consists of cohesion of values, preferences and policy outputs between different EU member states and EU institutions (Rhinard and Sjöstedt 7). Secondly there is a practical capability, which designates both the availability of policy instruments and the capability to use those instruments (ibid.). Lastly, there is ‘consistency’, namely the ability to carry out its policies and previous commitments in a consistent fashion (ibid.). As we can see, Tsuruoka’s Expectations Deficit is also strongly related to the role of the EU as a global actor, however the focus is not so much on the capabilities of the EU as it is on the expectations that other actors have of the EU’s role.

The Rise of China and Its Implications for EU Foreign Policy

The rise of China, which started in the late 1970s with the reforms of Deng Xiaoping, led to great levels of economic growth, marking an end to its relative isolation during the Cold War. This is an important development for the EU’s foreign policy and its relationship with Japan: while economically speaking the latter was the biggest player in Asia until 2010, this would now be China. While the term ‘rise of China’ implies a rise out of nothing, it is interesting to note that in China, this has been referred to as ‘rejuvenation of China’, which designates a return to the past (Zhao 981). This past finds itself in the era before the ‘century of humiliation’, an era where China was humiliated (i.e., defeated militarily) by mainly Western and Japanese hands, starting from the First Opium War in 1839 and lasting until the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Before this time, China is portrayed as being the benevolent centre of East Asia, a discourse which justifies its claim to regional hegemony (Zhao 961-62). As we will see later on, this claim to regional hegemony does lead to a worsening of its relationships with other Asian countries.

The EU has traditionally searched for partners in the global arena, something which is linked with the EU’s multilateral vision and its self-image as a ‘force for good’ in the world. In the case of China, this quest goes back at least 20 and perhaps even 30 years (Smith 89). Here, the relationship was traditionally framed in economic terms and marked by tensions such as that between seeing China as a key source of cheap manufactured products and defending EU producers, or the framing of EU-China economic relations as either a challenge or an opportunity (Smith 81). While recent years have seen an increase in institutionalised cooperation, Holslag argued that this developed within a ‘strategic vacuum’, meaning that there is a lack of a firm definition of mutual interests and areas of common action, which leaves a big gap in the relationship (Holslag, paraphrased by Smith 92). This is caused by the tensions mentioned above and also the difference between EU and member state perspectives (Smith 92). This tension can be seen when deciding how to approach China, where some (such as France, Germany, Italy or the European Commission) have argued for a ‘strategic partnership’, ‘techno-political alliance’ or even an ‘emerging axis’ between the EU and China, while others (the UK, Poland, Scandinavian states and the European Parliament) warned against being too close to an illiberal regime (Wong 112-113).

According to Wong, this disparity between visions is rooted in an unfinished and unclear European vision of world order and the role of Europe in that order (Wong 113). He affirms that the driving forces behind EU interests in China are essentially economic motives, which have usually been pursued nationally rather than on the EU level. China here was seen mainly as an economic opportunity: it was not only a giant market for western goods, but also the world’s manufacturing factory (Wong 115). In the early 2000s, however, the possibility of cheap Chinese products ‘invading’ EU markets would become a political issue, setting the tone for much of the subsequent relations marked by conflicts over trade deficits, intellectual property rights, quotas, protectionism, and the EU’s refusal to grant market economy status to China (Wong 117). However, it must be noted that the relationship is not solely one of conflict: while the European Commission designates China as a systemic rival, it also designs it as a ‘cooperation partner with whom the EU has closely aligned objectives’, in areas such as fighting climate change or anti-piracy in the Gulf of Aden (European Commission and HR/VP).

Japan’s Foreign Policy Towards China

Just like it affected the EU, the rise of China is important for Japan, arguably even more so because of its relative geographical proximity. This importance is due to the fact that the rise of China has the potential to challenge US hegemony in the region, while Japan and the US have known an ever deepening alliance since WWII (Hughes 110). Many analysts, however, argue that Japan’s response has been limited: from a neorealist perspective, Japan defies their predictions of states’ behaviour because of its lack of a balancing impulse. From a constructivist perspective, the focus is more placed on Japanese anti-militaristic norms and values (Hughes 111-112). Hughes however, offers another view, arguing that Japan’s security stance is closer to ‘resentful realism’ which is driven not only by concerns about the rise of China and how to balance this but also doubts the reliability of US security guarantees (116).

Other domestic developments in China also play a role here, especially the Chinese Communist Party’s abandonment of communism as an ideology in favour of ‘patriotic education.’ This has had a negative impact on Sino-Japanese relations, since it has engendered a drive for restoration of its territorial claims with regards to Taiwan and Japan (Senkaku/Diaoyu islands), but also in the South China Sea, challenging US hegemony in the region (Hughes 127). This is accompanied by a shift in the balance of power: while Japan traditionally was the bigger economic power, this balance has now shifted in the favour of China. This is also coupled with an expansion of Chinese military, potentially surpassing the balancing capabilities of the Japanese Self Defence Forces and raising doubts about the capability of the USA to counter threats to Japanese security (Hughes 136-137). This was only exacerbated by the Russian annexation of Crimea, where Obama noted that the USA would not automatically intervene militarily in such disputes and preferred to seek diplomatic approaches (Hughes 139).

In this context, Japanese presidents Abe and Asō have sought to articulate a ‘values-oriented diplomacy’ based on Japan’s internationalism, promotion of democracy, liberal market economy, human rights and rule of law, which implicitly contrasts with China. This became evident in Abe’s concept of ‘the Arc of Freedom and prosperity’, a group of countries throughout the world allegedly united by these universal values (ibid.). In particular, this cooperation has been deepened with ASEAN states, where it has stressed the importance of international laws and norms which cover the freedom of navigation and handling of territorial disputes, encouraging all states to adhere to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Japan has also developed ‘strategic partnerships’ with Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia (Hughes 140). At the same time however, the ‘values-oriented’ diplomacy has often been a failure, in part because of Japan’s own history both in colonial expansion and in tolerance of authoritarian regimes in favour of economic development (Hughes 142).

When it comes to Japanese foreign policy discourse, this values-oriented diplomacy can be seen in the same light as Normative Power Europe: here we also find a great emphasis on values and the ‘rule-based global order’, as we will see later in its discourse surrounding the South and East China Sea. This arguably comes from an integration of Japanese (and universal) norms into its foreign policy, which would make it possible to speak of a ‘Normative Power Japan’. Midford, however, argues that this is not actually aimed at promoting common values but rather at containing China, which means that in reality, it provides little ground for intensifying EU-Japan cooperation (46).

The EU’s Foreign Policy Towards Japan

Although as previously mentioned, the EU and Japan are constructed as close like-minded partners united by shared values in official documents, most scholarly sources paint a different picture. Söderberg et al. conclude that there is untapped potential and that Japan-EU security cooperation is more likely to be in soft or non-traditional security. Here the two powers have different threat perceptions: where the EU focusses largely on Russia and its annexation of Crimea, Japan is more concerned with Chinese intrusions in its own territorial waters and in the South China Sea. At the same time however, Tokyo was willing to support sanctions on Russia following the annexation of Crimea, which does ‘show a willingness to support European policies aimed at safeguarding international legal norms and standards’ (245). Given this divergence in perception, it is also not surprising that Japan prioritises cooperation with the U.S. above Europe: the U.S. is better equipped to give Japan hard security guarantees, while the EU’s capabilities in the region remain limited. This is especially true for Abe, who could be seen as the ‘wrong’ prime minister to expand EU-Japan cooperation, since Abe’s foreign and security policy priorities are firmly based in the Japanese-American alliance and the expansion of Japanese military capabilities (Berkofsky 23). While China’s more assertive regional policies could have been an incentive to intensify EU-Japan security cooperation, this has not led to any EU-Japanese policies aimed at countering this, something which is caused by member states that often have reservations about damaging their economic ties with China. While the EU officially maintains that it does not take sides in territorial disputes, its unwillingness to bring up issues which China sees as its core interests (i.e., Taiwan, Tibet and contested maritime claims) on the EU-China High Level Strategic dialogue does raise doubts in Tokyo about European support for its policies and means that actual security cooperation does not live up to what would be expected from a ‘natural ally’ (Berkofsky 27-28).

This is problematic because as Tsuruoka argues, ‘for the EU to be more effective in Asia, cooperation with those who share values and interests like Japan and South Korea is indispensable and incorporating this into its overall Asia strategy is an urgent necessity’ (105). Here, he cites Alyson Bailes and Anna Wetter, who pointed out that ‘the success of the EU’s policy [towards China] is interdependent with the success of the policies of the USA and perhaps also of Japan and Russia, with their ultimately quite similar goals regarding China but their often different balance of tone and modalities in trying to get there’ (ibid.). This can be seen in Song and Cai’s observation that the EU’s statements on territorial disputes in the East and South China Seas are less harsh than the Japanese equivalents, but both do support the verdict of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) which ruled that China does not have historical rights to the waters in the South China Sea (Song and Cai 234-35). At the same time, the EU seeks less to militarily encircle China, but rather wants it to make a constructive contribution to regional stability (Song and Cai 235). The EU and Japan share many core values, values which are fundamentally different from those which China promotes. European countries, however, do have a contradictory stance concerning China: while Brussels welcomes trade and business ties with China, it also sees a necessity to export its own norms and values to it. In the security area, where Chinese territorial claims challenge the existing international order, the EU seeks to remain neutral in practice and avoids choosing between Japan and China. While it does sometimes condemn its actions, it is far less active in doing so than Japan, which makes substantial cooperation more difficult (Song and Cai 239).

Discourse Analysis – The EU and Japan in the South China Sea Dispute

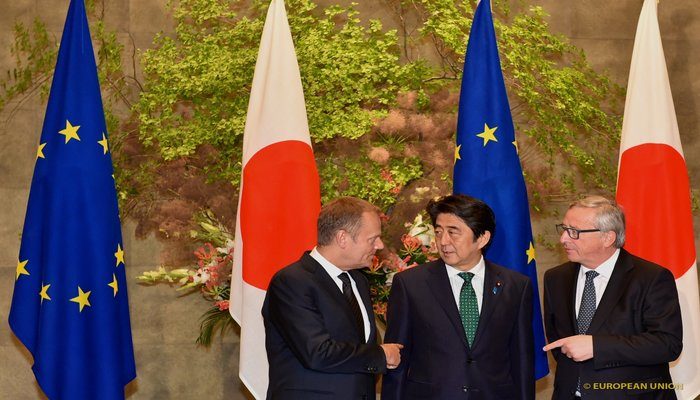

In the following part, I will analyse the language used surrounding the South and East China Sea in both EU official discourse and Japanese official discourse in order to see whether we can distinguish any divergence in positions between Japan and the EU or in their articulations. In the EU-Japan summits, Japan’s territorial conflicts have traditionally been a marginal subject, with only small parts of the statement referring to the South and/or East China Seas and a greater focus on trade relations. In the next part of this paper, I will analyse the statements regarding the South and East China Sea in the 23rd and 26th EU-Japan summits and 20th EU-China Summit, in order to shed light upon how the EU seeks to maintain neutrality without either alienating China or damaging its relationship with Japan. The joint statement of the 23rd EU-Japan summit (2015) mentions ‘uncertainties in the regional security environment’, and condemns ‘all violations of international law and of the principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity of states,’ while underlining ‘the need for all parties to seek peaceful, and cooperative solutions to maritime claims, including through internationally recognised legal dispute settlement mechanisms’. While the language avoids explicitly condemning China, when placed in the context of China’s December 2014 statement that it ‘will neither accept nor participate in the arbitration thus initiated by the Philippines’ (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China), it becomes clear that it is aimed at China in particular.

The 26th EU-Japan Summit (2019) echoes the same language reaffirming the EU and Japan’s ‘shared commitments to addressing the issues of […] maritime security, underlining the critical importance of refraining from the threat or use of force and unilateral actions that are against international law, in particular the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in the East and South China Seas. Notably, the use of language here differs greatly from that in another, though larger conflict, since they also reaffirm their commitment to resolving the issue of ‘Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea’. In the latter, the agent, Russia, is named directly, and their actions are condemned as an illegal annexation, while in the first example, this is not the case, and the emphasis is on international law. As for Japan, its discourse surrounding the South China Sea can be seen as similar in that both place emphasis on the international law. At the same time, Japan’s reaction to the verdict of the PCA is harsher since it argues that the ‘award is final and legally binding on the parties to the dispute under the provisions of UNCLOS’ and therefore, expects that ‘the parties’ compliance with this award will eventually lead to the peaceful settlement of disputes in the South China Sea’, although China is not named explicitly (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, ‘Arbitration’). In his address on the 13th ISS Asian Security Summit (2014), Shinzo Abe made a similar point. Here he reformulates the law of seas to three principles, which in fact, are ‘common sense’. These principles are the justifying of claims based on international law, the non-use of force in driving these claims and the settling of disputes by peaceful means. Here Abe expressed his support for the Philippines and Vietnam, since their approach to resolve this issue is ‘truly consistent with these three principles.’ However, Abe here brings up a previous agreement signed with China, which ‘has not led’ to putting in place the mechanism that it was designed for (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, ‘Shangri-La’). While language here is neutral—‘has not led’ is passive—and does not attribute agency to either Japan or China and leaves open room for circumstances outside of either parties’ control, it does raise doubts about China’s willingness to live up to its agreements.

Therefore, what we can conclude is that, in general, both parties have condemned China’s actions in the South China Sea, although Japan has been more assertive in doing so. Japan here too, has mainly used indirect language to condemn China’s actions, using similar language to the EU in referring to international law. However, it has also expressed support for its regional allies, namely the Philippines and Vietnam, something which Europe did not explicitly do, though it might be expected when considering Japan as ‘one of the EU’s closest partners.’ In light of the information previously set out in this paper, an explanation can be found in the following three reasons: first, there are the interests of individual member states which are often marked by economic interests and differ per country, which makes it difficult to create a common foreign policy. Secondly, there are the different foreign policy priorities between the EU and Japan: where the EU is focused mainly on Russia and the Middle East, Japan’s main concern is China. Lastly, there is the EU perception of China, which has been designated as both a systemic rival and an important partner for cooperation in certain areas, which makes the EU reluctant to condemn China, since it risks worsening relations with a partner that is also cooperative in certain policy areas.

Conclusion

Since the rise of China, the EU has prioritised cooperation with China over Japan, while Japan has been more weary of China and responded with what Hughes calls ‘resentful realism’. This means that, while Japan and the EU do describe themselves as close partners and both have given a central role to values in their foreign policy discourse, in reality it is difficult for them to form a common position or to support each other. One case where this becomes clear is the South China Sea crisis. Even though the EU and Japan share concerns, the latter does not condemn China’s actions to the same extent as the former, creating a situation where the EU refuses to side with one of its ‘closest partners’ against a ‘systemic rival.’ This comes from a desire to not alienate China, however, at the same time, it means foregoing cooperation with partners that are closer to the EU when it comes to values and interests, something which is crucial if it wishes to have influence in the region. The current situation then also exerts a negative influence both on EU actorness in the region and on the role of the EU as a ‘normative power,’ thereby raising various questions: what instruments does the EU have available to ‘enforce’ international law in the South and East China Seas? Assuming that it has the capability, would the EU be willing to forego deeper economic ties with China in order to enforce international law? To what extent could other countries with shared values, such as Japan, count on the EU’s support? However, at the same time the current discourse also has its merits. First, it allows the EU to stay neutral and in not alienating China, it can be more cooperative in certain areas such as climate change. Secondly, staying neutral in this conflict allows the EU to direct more of its resources to areas that are seen as more important. As far as foreign policy is considered, this means largely maintaining stability in both major areas targeted by EU foreign policy: the Eastern and the Southern neighbourhoods. Here, instability more directly impacts the EU and its member states than it does Eastern Asia with, for example, the migrant crisis in the Southern Neighbourhood being a more direct concern for the EU.

Bibliography

‘Arbitration between the Republic of the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China regarding the South China Sea.’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 12 July 2016, https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press4e_001204.html

Berkofsky, Axel. ’The strategic partnership agreement New and better or more of the same EU–Japan security cooperation?’, edited by Axel Berkofsky et al. The EU-Japan Partnership in the Shadow of China: the Crisis of Liberalism. Routledge, 2019, pp. 17-39.

Council of the European Union. Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe. A Global Strategy for the EU’s Foreign and Security Policy. June 2016. http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/top_stories/pdf/eugs_review_web.pdf

‘Countries & Regions The 13th IISS Asian Security Summit -The Shangri-La Dialogue-Keynote Address by Shinzo ABE, Prime Minister, Japan.’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 30 May 2014, https://www.mofa.go.jp/fp/nsp/page4e_000086.html

European Commission and HR/VP. EU-China – A strategic outlook. European Commission, 12 March 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/communication-eu-china-a-strategic-outlook.pdf

‘EU-Japan relations’. European External Action Service, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage_en/48463/EU-Japan%20relations

Hughes, Christopher W. ‘Japan’s ‘Resentful Realism’ and Balancing China’s Rise’. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, Vol. 9, no. 2, 2016, pp. 109–150.

Midford, Paul. ‘Abe’s pro-active pacifism and values diplomacy Implications for EU–Japan political and security cooperation’, edited by Axel Berkofsky et al. The EU-Japan Partnership in the Shadow of China: the Crisis of Liberalism. Routledge, 2019, pp. 40-58.

Neuman, Marek and Stefan Stanivuković. ‘Introduction: EU Democracy Promotion in Its Near (and Further) Abroad Through the Prism of Normative Power Europe.’ Democracy Promotion and the Normative Power Europe Framework edited by Marek Neuman, Springer, 2019, pp. 1-10.

‘Position Paper of the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Matter of Jurisdiction in the South China Sea Arbitration Initiated by the Republic of the Philippines’. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 7 December 2014, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1217147.shtml

Rhinard, Mark and Gunnar Sjöstedt. The EU as a Global Actor: A new conceptualisation four decades after ‘actorness’. THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS, 2019.

Smith, Michael. ‘EU Diplomacy and the EU–China strategic relationship: framing, negotiation and management’. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, vol. 29, no. 1, 2016, pp. 78-98.

Song, Lilei and Liang Cai. ‘From “wider west” to “strategic alliance” An assessment of China’s influence in EU–Japan relations’, edited by Axel Berkofsky et al. The EU-Japan Partnership in the Shadow of China: the Crisis of Liberalism. Routledge, 2019, pp. 227-242.

Tsuruoka, Michito. ‘Expectations deficit’ in EU-Japan relations : Why the relationship cannot flourish. The European Union and Asia: What is There to Learn?. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2008, pp. 107-126.

Wong, Reuben. China’s Rise: Making Sense of EU Responses. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, 2013, pp. 111-128.

Zhao, Suisheng. ‘Rethinking the Chinese World Order: the imperial cycle and the rise of China’. Journal of Contemporary China, vol. 25, no. 96, 2015, pp. 961–982.

Written by: Martijn Kooi

Written at: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Written for: Cristina Blanco Sío-López

Date written: June 2019

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Balancing Rivalry and Cooperation: Japan’s Response to the BRI in Southeast Asia

- Why Is China’s Belt and Road Initiative Being Questioned by Japan and India?

- Politics of Continuity and US Foreign Policy Failure in Central Asia

- China’s Increasing Influence in the Middle East

- Struggle and Success of Chinese Soft Power: The Case of China in South Asia

- Analysing EU Foreign Policy on Russia before the 2022 Invasion of Ukraine